Who Was Lawrence R. Brown?

Biographical Notes on the Author of The Might of the West

Margot Metroland

1,539 words

It is intriguing, and often maddening, to research an author or historical figure and discover that there’s very little material to be found. With today’s newspaper and genealogical databases, such lack of information is itself suspicious. Perhaps the person just didn’t want to be found, or spent his life trying to keep his name out of the newspapers. And there’s always the possibility that for practical or professional reasons our subject wrote mostly under pseudonyms, such as “Lewis Carroll” or “Ulick Varange.”

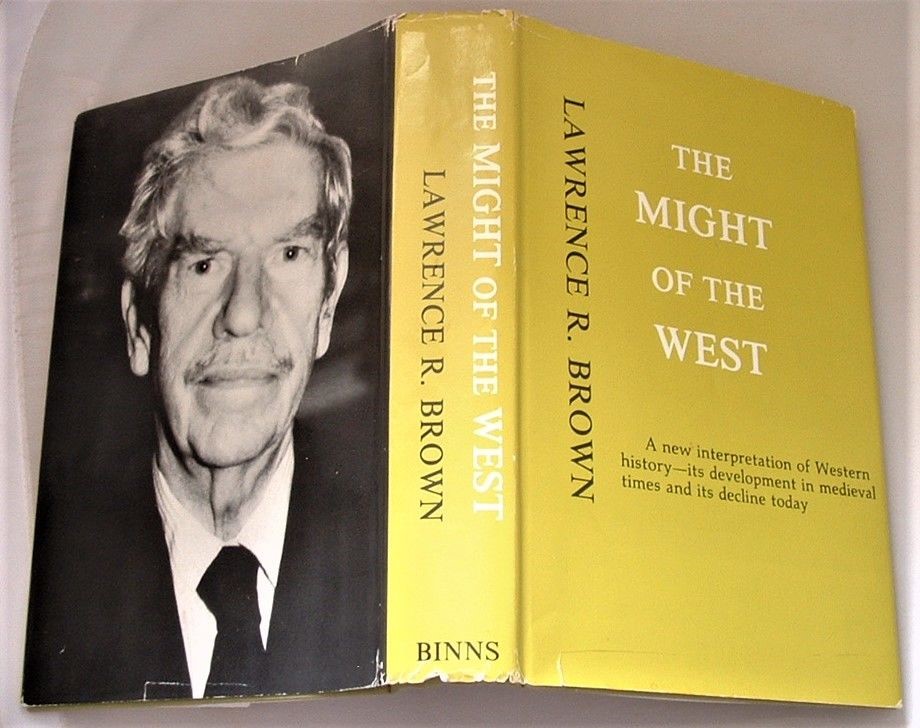

Researching the life of Lawrence R. Brown (1903-1986) presents us with yet another obstacle, what you might call the “James Jones” gambit. If you’re an author with a common moniker, you might be able to sign your name to your writings and “hide in plain sight,” if you like. Lawrence R. Brown often looks to be an example of such self-willed obscurity. He wrote one immensely readable philosophy of history, The Might of the West (first edition 1963, second hardbound edition 1979), which was very well received in certain quarters. But little else was known about him.

While sorting through the many possible Lawrence R. Browns in the online databases, I briefly became convinced that Brown had held a sensitive United States Department of Defense position for many years. Alas, my favorite candidate turned out to be an interesting guy, but the wrong guy. His relatives had never heard of him publishing any sort of book.

The necessary clue came from syndicated columnist John Chamberlain, who praised Brown and his book in 1966.[1] His encomium for Brown is an eye-opener, and alerted me to the varied interests of that polymath. Under the headline “Is United States ‘Banana Republic’?”, Chamberlain’s column mocks the single-assassin verdict of the Warren Commission’s report on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. His piece de resistance is a recent article by our obscure Mr. Brown, here described as both “engineer” and “philosopher of history.” A couple of paragraphs from the Chamberlain column will serve here as a précis:

So let’s turn to a remarkable article by Lawrence R. Brown, “Kennedy’s Assassination: Let’s Solve It,” which appeared in September in the first issue of a new Catholic magazine called Triumph. Mr. Brown is an engineer, but on the side he is a gifted philosopher of history, as his only book, a bulky tome called The Might of the West, abundantly proves.

Brown goes about establishing a thesis the way Charles Lindbergh prepared for his pioneer flight across the Atlantic, leaving nothing to chance. His article on the assassination does not deal in motives; it simply concentrates on what might be called the “hardware” questions. One such question is raised by the author’s insistence that spectrographic analysis could not establish that all the bullets or metal fragments came from Oswald’s Mannlicher-Carcano rifle. Brown suggests that two separate sets of bullets may have been involved, or that there may have been “planted clues.”

— John Chamberlain column, November 30, 1966, King Features Syndicate

You can buy Francis Parker Yockey’s The Enemy of Europe here.

Based on Chamberlain’s claim that Brown was an engineer, it appears that the real Lawrence R. Brown was Lawrence Roscoe Brown, a chemical engineer who worked for 37 years as a senior manager for Publicker Industries, a Philadelphia beverage distillery and industrial-chemical manufacturer. He was born in Stonington, Connecticut on September 1, 1903 and died in a Burlington, Vermont hospital on March 31, 1986.[2] In between, Brown lived in New York City, suburban Philadelphia, and the southern Maryland exurbs of Washington, DC (La Plata, Maryland).[3]

Chamberlain’s column also tells us that Brown had written a soon-to-be-published second book, an in-depth technical criticism of the Warren Report. This book appears to be lost to history. Why? Perhaps it was too granular and techie: Brown’s mastery of spectrographic analysis and other abstruse metrics would not have been readily imparted to a wide audience. (That three-page 1966 Triumph article is eye-glazing in its detail.[4]) Or maybe Brown couldn’t find a publisher because the market was thought to be saturated with JFK assassination “conspiracies.”

And then there’s the fact that Brown didn’t have good relations with his old publishing company, which had passed to unfriendly hands shortly after publication of The Might of the West. In his 1979 review of the second edition, Revilo Oliver suggests its new owners had actively suppressed distribution of the book.[5]

Brown contributed essays and commentary to Triumph[6] sporadically from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. In December 1966 he turned to Catholic liturgy, presenting arguments for the preservation of the Tridentine Mass in a piece called “The Language of the West.” Vernacular liturgy is deficient, he writes, because it makes divisions along national and linguistic lines. “National churches” are popularly understood as a direct result of the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century, yet that was not, writes Brown, the Reformers’ intent. They merely wanted a reformed, more democratic, universal church.

“And now,” Brown grieves,

exit the Latin Mass. The Christian West, even in its bare form, cannot be said to exist when there is no longer so much as a symbol of it surviving, if only as a memorial to a common civilized past.

— Triumph, December 1966

This bears close comparison to parts of The Might of the West, particularly Brown’s depiction of the unity of the Christian West during the Middle Ages. In his gracious and appreciative 1979 review of that book, Revilo Oliver basically upheld that viewpoint, refusing to be distracted by Brown’s distinctly Catholic apologetics. The Protestant Reformation was a disaster, Prof. Oliver agreed, dividing the West into petty-state rivalries and fratricidal wars.

A more surprising piece of commentary came in March 1969 when he wrote a long letter to Triumph, taking a MacArthurish, “no substitute for victory” stance on America’s Vietnam policy. He slammed the undeclared war as a defeat, inasmuch as

our military forces have failed to attain the political objective which has been publicly declared to be the purpose of the use of military force in this area: the elimination of externally supported Communist military operations in South Vietnam . . . [The clear political intention of US policies] is: “Avoid any action that will seriously irritate the Soviet Government.” — Triumph, March 1969

Triumph had recently taken an editorial stand against the war, on the practical grounds that America didn’t really want to win it. This drew a fierce letter in January 1969 from professor/science fiction writer Jerry Pournelle in Los Angeles, who denounced Triumph’s editors for defeatism.

Triumph immediately responded with an editorial in the same issue, denying its defeatism while denouncing both the ongoing Paris Peace Talks and the war itself. Lawrence Brown’s disgusted response in the March issue manages to agree and disagree with both sides. It is a mildly interesting fracas over one of the more dismal geopolitical topics of the time.

That original 1963 Obolensky edition can be read today at the Internet Archive; but not, alas, the 1979 edition, which Prof. Oliver informs us was a photo-offset reproduction of the original edition’s pages. Used copies now go for $200 or more online. Further trivia: The 1979 edition was brought out by Joseph J. Binns Publisher of Washington, DC and New York, a company that appears to have specialized in lush, “coffee table” travel-picture books, but which also published works by Martin A. Larson, Ph.D., a freelance scholar and longtime columnist for The Spotlight.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Notes

[1] John Chamberlain, an economic historian and journalist, is scarcely remembered today, but he was very influential in the conservative movement of the 1950s and ‘60s. Among other things he wrote the Introduction to God and Man at Yale, a boost which former Yale Daily News Chairman William F. Buckley, Jr. later credited with “changing the course of my life.” Chamberlain was a columnist for King Features for 25 years. From Wikipedia.

[2] Burlington, Vermont Free Press obituary, April 4, 1986.

[3] Residential information gathered from Ancestry.com and Triumph magazine, March 1969.

[4] Lawrence R. Brown, “Kennedy’s Assassination: Let’s Solve It,” Triumph, September 1966. Available at Internet Archive.

[5] Revilo Oliver’s review has been reproduced in many places, including Instauration (December 1979), Counter-Currents, and National Vanguard. The last-named includes Prof. Oliver’s intriguing notes on how it was originally published by entrepreneur and investment banker Ivan Obolensky, who then sold off his book company to someone who had no interest in Brown’s big-brained tome. Oliver’s notion that The Might of the West was deliberately suppressed almost certainly came from the author himself.

[6] Triumph , which ran from 1966 to 1976, was founded by William F. Buckley, Jr.’s brother-in-law L. Brent Bozell, Jr., a sometime National Review editor who disliked the lukewarm conservatism and cultural secularism of that magazine. Triumph‘s masthead and contributors’ list overlapped a good deal with National Review‘s, though it was much more Catholic, boasting Willmoore Kendall, Jeffrey Hart, Russell Kirk, Otto von Habsburg, Hugh Kenner, Jerry Pournelle, and Bill Buckley’s younger brother F. Reid Buckley. Eventually the two magazines disavowed any connection. Lawrence R. Brown is frequently listed on the masthead as a contributor or contributing editor. The major advertisers, unsurprisingly, were conservative book publishers and Rightist Catholic businessmen. Arlington House books, Conservative Book Club, and Patrick Frawley’s Schick razor blades bought prominent, full-page insertions at the front of the book or on the back cover. When Triumph folded in 1976, its torch was carried on by another Bozell creation, the Christian Commonwealth Institute, as well as Christendom College in Virginia.

Who%20Was%20Lawrence%20R.%20Brown%3F%0ABiographical%20Notes%20on%20the%20Author%20of%20The%20Might%20of%20the%20West%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 3

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 2

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 1

-

Looking for Anne and Finding Meyer, a Follow-Up

-

The Origins of Western Philosophy: Diogenes Laertius

-

Birch Watchers

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 6: Znaczenie filozofii dla zmiany politycznej

-

Elizabeth Dilling on the Evil of the Talmud

20 comments

Thanks for bringing this individual to our attention.

Researching this, I thought I was merely assembling notes for a new edition of The Might of the West, and/or some sort of Wikipedia entry. Brown’s self-willed obscurity I describe was almost certainly intentional on his part.

If you haven’t seen TMOTW, try to read the first edition available at archive.org. I believe the book is more accessible than Spengler, Toynbee, or Yockey, as it’s basically a digression on Western European history, and doesn’t throw abstruse philosophy at you (though the math and technics, Brown’s métier, can get pretty deep).

Spengler’s concise late work Jahre der Entscheidung – oddly abbreviated in translation to The Hour of Decision is quite an easy read. TMOTW I personally found heavier going than it or Imperium. I found it a shame that it has hardly any footnotes, endnotes or bibliography, seemingly its targeted at polymaths who already know most of these things. I certainly didn’t. The archive.org uploads are very new and are both ‘1 hour borrow only’ presumably because of the copyright holder’s interest in (suppressing?) the work.

Thanks for this biographical research. It’s good to have more than less info about substantial figures in our movement, and it’s good that someone’s willing to do the legwork to obtain it.

I have a virtually new hardback copy of The Might of the West. I gingerly read it decades ago once through, always intending to give it a second, closer read later, at which time I would have done my customary underlining, highlighting and general textual ‘engagement’. But I never did get around to it. I wonder if I should sell it and make a bit of money? I’m greedy for books, and hate parting with any, especially ‘movement’ classics, but I do have so many books … and a few hundred bucks for one might be worth it.

An interesting bit of research, Margot. It shows that even though the 20th century wasn’t that long ago there are all too many books and authors that have slipped through archives – something I realised when trying to find copies of Roger Pearson’s books. I hope there are efforts to find and digitise such books.

That said, Brown’s book does not sound appealing in the slightest. A unified west is a tiresome christian apologetic that doesn’t stand up to the tiniest bit of historical scrutiny, just like the fiction that the crusades were about saving Europe from arabs, berbers and turks.

Peter Frankopan, of Croatian and Dutch ancestry , author of The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, published a book called The First Crusade: The Call from the East in 2012, the contention of which was essentially that Alexios Komnenos manipulated the Occident to come east and help him push back the near total overrun of Anatolia by the Turks after Manzikert in 1071. Listen to Episode 208 of The History of Byzantium by Robyn Pierson on acast.com or Apple podcasts for an interview with him.

The bits and pieces Lawrence Brown published in Triumph do not mean that his argument was a religious or sectarian one. Triumph just happened to be the most available and respectable outlet. For all I know, Brown himself was unchurched. The Might of the West is as much about mathematics and technics as it is about art, philosophy, theology; and if it looks hard-going for some, that could be the reason why.

In a nutshell, Brown’s argument is that the core culture of the West arose not out of some flimsy flowering in the Renaissance, or revival of interest in preposterous “science” from Ancient Greece or Rome (Ptolemy, Galen), or hermetic occultism handed to us by Arabs and Jews—those clichés we’ve all heard—but rather was home-grown in the Middle Ages, by a unique people.

A friend recently sent me a National Alliance book flyer from the early 1980s. Right up front there you have Lawrence R. Brown’s The Might of the West and Sir Stephen Runciman’s The First Crusade (as well William Gayley Simpson’s Which Way, Western Man?). I owned them all in the 80s, do not now, alas.

I see, thank you for sharing. Perhaps it is worth my time to read after all.

A few years ago the late Karl Winn of Black House Publishing, sought to republish The Might of The West, but he commented that this was rejected by Brown’s relatives. Who these relatives are and the nature of their control over his literary estate, I do not know.

I had The Might… sitting unread for decades, but it is indeed a wonderful book. Oliver seems to have regarded it as equal in worthiness to The Decline of The West, and Imperium.

Another fine piece of biographical research, which will hopefully prompt a revival of interest in Brown’s book.

Thanks Kerry. It is sad that the book will not likely be reprinted. But at least it is up on Archive.

I asked Margot to do this research because she is a genealogy whiz, and I was shocked that there was not even a stub on Wikipedia giving Brown’s dates of birth and death.

It would be good to ensure that his articles are also made available easily online.

Musing on the possibility of winding back the duration of copyright ( when first introduced in Philadelphia it lasted fourteen years, with an option to extend once if the author survived, it’s now seventy years post-mortem or ninety-five after publication) , Wikipedia informed me that an ‘American’ novelist, Mark Helprin( New York Jew, Harvard, Oxford, Israeli-American, IDF, Claremont, CFR – the cursus honorum!) promoted perpetual copyright in an op-ed in the NYT with the argument that it was unjust to deprive the aged grand-children of authors whilst greedy corporations raked in the profits. Given his pedigree I hate to admit that he has a point and it ought to be the case that some of the profits from booksales should revert to the heirs, so long as these have a personal connexion to the author, and decreasing very slowly on a sliding scale from date of publication. However the right to veto re-publication if it exists at all ought to expire on the death of the author. This is an issue which would help us, without being seen as overtly left-right political by the public. I don’t see J. Greenblatt being supportive.

An interesting subject. The late libertarian, Murray Rothbard, thought copyright should be in perpetuity. Of course, authors could also decree, perfectly consistently with the “ethics of the free market” as Rothbard saw it, that their copyrights expire at their deaths, or after a set number of posthumous years, thus eventually putting their works back into the public domain.

The real conundrum, at least from a libertarian standpoint (which I tend to find persuasive on property rights matters), occurs at the intersection of copyright and testamentary law, as maybe has happened here. What if Brown didn’t specify in his will (if he even had one) that he wanted TMOTW to be placed in public domain? So the copyright would (did) revert to his heirs (who, note, might just be identified via statutorily defined genetic distance; ie, could be persons who were barely known, or even unknown, to Brown, not ones he affirmatively wanted to have ownership of the copyright). And if those heirs are antifa? Should they get to keep an author’s work permanently away from the public, even if the author would have wanted the precise opposite?

Obviously, within a libertarian schema, the correct approach for an author concerned about ensuring his posthumous readership would be to specify the relinquishing of copyright at death (or spouse’s or children’s death, etc). But if an author should have died intestate, it seems like copyrights should be seen to have died with him, thus allowing his book to be republished (perhaps with some statutorily determined level of royalties going to his legal heirs, as you suggest).

I’m not a doctrinaire libertarian and I find it ironic that Rothbard was so all-in on copyright with its inherent restrictions on liberty. Intellectual property is not real property but a restraint on man’s God-given right to copy. Pharmaceuticals are treated along similar lines to the 18th C. Philadelphia law and after fifteen years or ao it’s a free-for-all for generic manufacturers.

I don’t see why the author or anyone else has to be given the right to legal sanction of anyone who republishes a work unaltered from the original, as long as the republisher pays the requisite royalty. The reality of this issue is that it is bound up in the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works and myriad of so-called ‘Free Trade Agreements’ which make it difficult for any country except perhaps the USA to alter their laws.

When Brown died, he had been declining into dementia for a while, and presumably was not in control of his own affairs. I suspect he otherwise would have made over the rights to TMOTW, and that tantalizing Kennedy Assassination manuscript, to an appreciative organization. Furthermore, he’d remarried a few years earlier, in Burlington. The new wife and her kin are unlikely to have been able to appreciate his work. And as for his blood children, family members hardly ever read the work of a writer in the family.

Why can’t Counter-Currents print “The Might of the West,” they have done several versions of “Imperium?” I also recommend “Which Way Western Man,” by William Galey Simpson. It has been several years since I have read these books, I need to revisit them.

I believe it’s still under copyright, so permission would need to be obtained.

And it doesn’t take a genius to figure out why <i>The Dispossessed Majority </i> has been out of print for quite a few years.

Because the author has been dead for years.

No one wants to republish it? Seems odd, since it sold several hundred thousand copies during his lifetime.

Hello Margot, this was a great article and you’re doing fantastic research. I wanted to leave a comment on your Willis Carto article but the section was locked. I know that I, and I’d guess many of your other readers, would love to hear more about your experience with the Youth For Wallace movement. Groups like this deserve to be remembered, memorialized, and turned to for lessons for today’s activists, but its almost impossible to find anything about them online. Personally, I’ve been having a lot of fun digging into the history of ‘Occident,’ a French youth nationalist group which counts a couple ministers of state among its alumni.

Since I’m commenting on one of your articles for the first time, I’ll also say that you are by far my favourite columnist here. Your erudition, knowledge of the American literary scene, and keen sense of humor make for really delighftul reading. Thank you.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment