2,559 words

Part I here, Part II here, Part III here, Part IV here, Part VI here

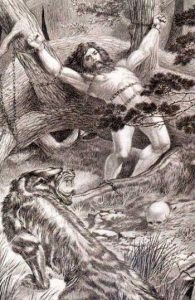

In our last installment, we saw that after Sigmund pulls the sword from the tree Barnstokk, Siggeir (who has just married Sigmund’s sister, Signy) offers to buy it from him. When Sigmund refuses, Siggeir immediately begins plotting revenge. On a pretext, he takes Signy and leaves the wedding feast early, inviting Volsung and his ten sons to visit him in Götaland. Three months later, travelling in three ships, Volsung, his sons, and their men arrive at Götaland late at night. They are met by Signy, who warns them that they are walking into an ambush, and that Siggeir has assembled a mighty army. Unsurprisingly, Volsung refuses to flee, saying that it would be dishonorable. In the ensuing battle, Volsung suddenly and inexplicably “falls dead” in the middle of his troops. His ten sons are taken prisoner by Siggeir and pinned under a great tree trunk in a dark part of the forest. For the next nine nights, Siggeir’s mother, who has taken the form of “an old she-wolf, huge and ugly,” eats one of the brothers, until only Sigmund is left. Before the tenth night falls, Signy sends a servant to Sigmund, who spreads honey over Sigmund’s face and in his mouth. That night, the she-wolf approaches Sigmund, sniffs him, and begins licking the honey off his face. When she sticks her tongue into his mouth, Sigmund bites down hard. The wolf struggles so fiercely her tongue is torn out at the root, and she dies on the spot. In all of this we see the hand of Odin at work, even in the sudden death of Volsung. Why did nine brothers have to be killed? As we will now see, the answer is that it is Odin’s plan to force Sigmund and Signy together so that they can breed a pure Volsung, the perfect warrior.

Chapter 6. How Sigmund Killed the Sons of Siggeir

When the wolf struggles to free herself from Sigmund, she manages to shatter the tree trunk under which Sigmund is pinned, freeing him. Sigmund ventures deeper into the forest and hides out. Anxious to learn whether he is living or dead, Signy dispatches a messenger who manages to find Sigmund, and to get the entire story from him. Then Signy herself ventures into the dark forest and meets secretly with her brother. They plot revenge, and Signy suggests that Sigmund build himself a turf house in the forest and continue to hide there. Turf houses were built by piling earth over a wood-frame roof, which provided effective insulation. Sometimes they were actually built into hillsides (which we imagine may have been the case with the house Sigmund builds, as it would have provided effective camouflage). The saga writer would have been quite familiar with turf houses, as they were very common in Iceland, and were to be found in Norway as well.

Years now pass, during which Signy makes clandestine visits to Sigmund, bringing him whatever he needs. For his part, Siggeir believes that all the Volsungs are dead. In these intervening years, Siggeir and Signy also have two sons. When the eldest turns ten, Signy sends him into the forest to live with Siggeir. Brother and sister have agreed, you see, that Sigmund needs the aid of another male in order to exact his revenge upon Siggeir. He intends to raise the boy to help him in his plan. (How the boy’s absence will be explained to Siggeir is never discussed.)

When Signy’s son arrives at Sigmund’s turf house, deep in the forest, it is already late in the day. Sigmund greets him warmly and puts the boy to work making bread. The boy’s task is to take flour from a bag and make dough, while Sigmund steps out to gather firewood. However, when Sigmund returns, he finds that the boy has not even begun his task. The boys says, “I didn’t dare touch the flour bag, because there’s something alive in there.”[1] As we will see, there is indeed a poisonous snake in the bag. And it will become clear that this is no accident: Sigmund has placed the snake there as a test. It is a test which, in Sigmund’s eyes, this boy has clearly failed.

Sigmund therefore suspects that the boy might not be brave enough to assist him in his plans. When he meets with Signy again he tells her that “he didn’t feel like a man was near him, no matter how near the boy was.”[2] In other words, the boy is fundamentally argr, the Old Norse term for “unmanly.” This is no surprise, as he is the son of the jealous and treacherous Siggeir. What comes next always shocks readers. “Then kill him,” Signy advises. “He doesn’t need to live any longer.”[3] And Sigmund does just that. Winter passes, and during the winter after that, Signy sends her younger son to Sigmund. Here the saga writer tells us that “there is no reason to dwell on that story for long,” since the same thing happens all over again. In other words, the younger boy is put to the same test, and fails it just as his brother did, proving himself insufficiently manly. Once again, Sigmund kills the boy “at the request of Signy.” (How the deaths of these children are explained to their father, Siggeir, is never discussed.)

Now, one should be careful not to draw any sweeping conclusions from this about the qualities of Viking motherhood! As I noted in earlier parts of this essay, a major theme of the saga is that the Volsungs continually transgress moral and social norms. Remember that, with the Volsungs, Odin is breeding a clan of super-warriors whom he can harvest for his army of the dead. Such a race cannot prove itself within the constraints of society – it must break those constraints. Again and again, we therefore find the Volsungs being placed in situations where they not only break moral conventions but seem to exhibit a pronounced lack of ordinary human feeling. This includes a number of crimes committed against blood relations. In Chapter Two, for example, Rerir slaughters his uncles. The text makes clear that this would have been considered a great transgression, as shocking to our ancestors as it is to us: The saga writer tells us that Rerir did this “even though such a slaughter of near relatives had until then been unheard of in every way.”[4] And here, in Chapter Six, we find Signy complicit in the murder of her own children, perhaps the least forgivable of all crimes. We will see in Chapter Thirty-Eight, however, that Gudrun, the widow of Sigurd, will surpass Signy in heartlessness: She will behead her own children.

Chapter 7. The Origin of Sinfjotli

The murder of the two children leaves Sigmund without any obvious candidates for the male accomplice he will need in order to carry out the Volsungs’ vengeance on Siggeir. Pondering this problem, Signy hits upon a solution when she is visited by what translators usually render as a “very powerful witch” (as does Crawford) or “sorceress” (as does R. G. Finch). The Old Norse word is seiðkona, or “seidhr-woman,” a practitioner of the type of magic known as seidhr, which may have involved “shamanic” elements, including trance states. Signy asks the seiðkona “to change shapes” with her. In Old Norse, the term is skipta hǫmum, where skipta means (among other things) “to change, or shift.” Hǫmum is the dative plural of hamr: “shape or form.” Thus, skipta hǫmum is literally “to shapeshift.”

Hamr is a significant term in the Norse conception of human nature. Literally, it means “skin,” and can denote the outward shape of the person. However, it was thought that an individual could possess more than one hamr, and some of these could be “projected” in order to act at a distance – as a “double” of the individual, or in some other form (e.g., an animal form).[5] For instance, in the Ynglinga Saga (Chapter Seven) Snorri Sturluson writes, “Odin shifted shape [Óðinn skipti hǫmum]. At those times his body lay as though he were asleep or dead, and he then became a bird or a beast, a fish or a serpent, and went in the blink of an eye to far-off lands on his own or other men’s errands.” What Signy requests of the seiðkona, however, is that they exchange their outer hamr, or appearance. (Interestingly, the witch’s initial reply to her request is “that’s for you to decide,” as if she is reluctant – though she grants Signy’s wish.)

In the form of Signy, the witch goes to King Siggeir and stays by his side, going to bed with him at night. Siggeir suspects nothing. Meanwhile, in the form of the witch (who is described as quite beautiful), Signy goes to her brother in the forest. When she arrives, she claims to be lost. Sigmund invites her in, saying that he would not deny hospitality to a woman travelling on her own. He offers Signy a meal and, as they eat together, “Sigmund’s eyes were often drawn to the woman,” and he begins to desire her powerfully. After the meal, he boldly tells her that he wants them to share one bed that evening. “She said nothing against this,” the saga writer tells us, “and Sigmund laid her down on his bed three nights in a row.”[6] The pattern of lying with a woman for three nights is often found in Norse literature. In Rigsthula the god Rig (Heimdall) lies for three nights with each of the women with whom he sires the three classes of thralls, freemen, and nobles. In Snorri’s account of Odin’s theft of the poetic mead, he lies for three nights with the giantess Gunlod, who guards the mead. According to some theories, the product of their union is the god Bragi. In any case, the “three nights” formula seems to guarantee conception.

Sigmund has no suspicion whatever that the beautiful woman he slept with is Signy. After the three nights have passed, Signy returns home and exchanges shapes with the witch again. If she has any misgivings about having lain with her own brother, the saga does not mention it. This incest is, needless to say, yet another instance in which the Volsungs transgress basic moral conventions, seemingly without any feelings of hesitation or remorse, and it is probably the most notorious episode in the saga (and the one thing that most people remember about Wagner’s Die Walküre). Months later, Signy gives birth to a boy, whom she names Sinfjotli.

There is some debate about the etymology of this name. R. G. Finch writes that “[t]he name probably means ‘he of the ash- (literally ‘cinder’) gold fetter,’ and is thus a kenning for wolf, though –fjotli may be a variant of Germanic *fetulæ, ‘spotted,’ sin– being a later addition for alliterative purposes (in OE [i.e., in Beowulf] he is called simply ‘Fitela’. . . ) and his name could thus reflect his incestuous origin.”[7] If, indeed, the name does mean something like “he of the wolf,” then we may wonder whether in some way Sinfjotli owes some of his prowess to the wolf-tongue bitten off by Sigmund, and possibly ingested. (Though this is pure speculation – and, as speculation, probably goes a bit far.)

In keeping with the pattern we have seen before, Sinfjotli is described as another superb specimen of Volsung manhood: “he proved to be big and strong and good-looking, and very much of the Volsung type.”[8] When he turns ten, Signy resolves to send him to live with Sigmund in the forest. Before doing so, however, she decides to test Sinfjotli. We are told that before sending her doomed children to Sigmund (i.e., the sons she had with Siggeir), Signy had sewed their sleeves to the skin of their arms. “They had taken it badly,” the saga writer tells us. This is surely something of an understatement – and also an indication that they were likely to fail Sigmund’s test as well. Now Signy does the same thing to Sinfjotli, sewing his sleeves to his arms – but then she rips the shirt from his body, tearing his flesh! Sinfjotli does not react. “Volsung wouldn’t have thought much of such an injury,” she says to herself.[9]

When Sinfjotli arrives at Sigmund’s hut, immediately he is put to the test we’ve seen before: Sinfjotli is asked to make bread while Sigmund gathers firewood, thus leaving him alone. When Sigmund returns, Sinfjotli, unlike his ill-fated half-brothers, is almost finished making the bread. Cautiously, Sigmund asks him if he found anything unusual in the flour bag. Sinfjotli responds that he had the suspicion that something was alive in the flour when he started making the dough, but says, “I kneaded it down, whatever it was.” Sigmund is delighted, but tells him, “You can’t eat this bread tonight. You’ve ground down a huge poisonous serpent in it.” (We should note that, at this point, Sigmund has no idea that Sinfjotli is his son.)

The chapter ends with the sagaman telling us that while Sigmund was so strong he could eat poison without being killed, Sinfjotli could not do so. However, he can withstand poison falling on his skin. This small detail breaks a pattern we have seen so far: Usually, each new generation of the Volsung clan is stronger than the last. Sinfjotli, however, is not as strong as Sigmund – and his inability to ingest poison will, in fact, prove his undoing. Sinfjotli, indeed, is a rather disappointing character, and constitutes (as we shall see) a kind of puzzling dead-end in the saga – puzzling because of his origins in the notorious incest of brother and sister, and the implication that he is a pure Volsung. We expect great things of him, but he doesn’t deliver.

This flaw in the narrative structure of the story may reflect the fact that the saga writer is weaving together a number of different stories, which themselves existed in multiple variations. Wagner was certainly wise, in his revision of the story, to make Sigurd the product of the incest, and to drop the character of Sinfjtoli entirely. In the saga it is Sigurd, Sigmund’s second son, who will prove greater than his father. And one cannot help but see his most famous deed, the killing of the dragon Fafnir, foreshadowed in Sinfjotli’s killing of the “huge” (but, of course, much smaller) serpent in the bag of flour.

Sinfjotli has survived the initiation rite his half-brothers failed, at the price of their lives. In the next chapter, we will see that Sinfotli’s initiation continues, as Sigmund takes his son into the wilderness, to learn how to kill men. In one of the saga’s most famous episodes, Sigmund and Sinfjotli become werewolves, terrorizing the land. In this we will find echoes of the mysterious, half-forgotten initiation rites of the men who dedicate themselves to Odin, “leader of an army of ecstatic wolf-warriors.”[10]

Notes

[1] The Saga of the Volsungs with the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, trans. Jackson Crawford (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2017), 9.

[2] Crawford, 9.

[3] Crawford, 9.

[4] Crawford, 2.

[5] See Claude Lecouteux, The Return of the Dead, trans. John E. Graham (Rochester: Inner Traditions, 2009), 169-170.

[6] Crawford, 9.

[7] See Finch, The Saga of the Volsungs (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1965), 9-10, footnote.

[8] Crawford, 10.

[9] Crawford, 10.

[10] See Kris Kershaw, The One-Eyed God: Odin and the (Indo-) Germanic Männerbünde (Washington, D.C.: Journal of Indo-European Studies monograph No. 36), 8.

An%20Esoteric%20Commentary%20on%20the%20Volsung%20Saga%2C%20Part%20V

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Remembering Jan Assmann: July 7, 1938–February 19, 2024

-

A Pocket Full of Posies: Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, the Comic Part 2

-

Remembering G. I. Gurdjieff

-

Christmas and the Yuletide: Light in the Darkness

-

Nueva Derecha vs. Vieja Derecha, Capítulo 14: Religión Civil Racial

-

“The Rich Man’s Wealth Is His Strong City”

-

American Renaissance 2023: Reasons for Optimism

-

Nietzsche and the Psychology of the Left, Part Two

7 comments

Does Collin have a PayPal or anything to donate to him directly? Have very much enjoyed his work and would like to help support the continuation of it

Paypal has already unduly blocked Counter Currents, it wouldn’t surprise me if they started going after its individual authors as well if that kind of information became public. You could buy Summoning the Gods to support the author. It’s available on Ebay and Amazon it seems. I’ve been meaning to order a copy, greatly enjoyed these articles as well.

Volsunga Saga – first transhumanist epic!

“If, indeed, the name does mean something like “he of the wolf,” then we may wonder whether in some way Sinfjotli owes some of his prowess to the wolf-tongue bitten off by Sigmund, and possibly ingested. (Though this is pure speculation – and, as speculation, probably goes a bit far.)”

I’ll take the speculation one step further: reading this and remembering your previous articles I couldn’t help but wonder if perhaps Odin or another Aesir could have provided the seed for Sinfjotli as the level of trickery involved, failing to perform as expected and the giving birth to wolf-infused offspring reminds me of someone very close to him: Loki.

Excellent thoughts. As you point out, the transgressions mustn’t be seen as prescriptions.

Instead, they are part of the Indo-European psyche that seeks rectitude in life, and transgressions in mythos as catalyst for change.

This is also evident in the Bhagavad Gita and its larger epic, where kin kills kin, and proteges, masters. The whole is an affront so that we may be guided towards justice in this life, on this Earth, at this time.

We mustn’t let the times distort ours souls. We can endure.

Almost as if closest incest bears a very real risk of genetic deterioration… Obviously, in this particular case, it was useful in short term – Sinfjtoli could accomplish what his miscegenation-produced siblings couldn’t, but such “purity” has no future and ultimately leads to race’s decline.

IMO Wagner’s treatment of brother-sister incest is another instance of his work’s inferiority to its source material. Whether it was a product of expedience, or of saccharine 1800s free love culture, is another matter. There are truths in the source, in its primal rawness, that are lost in his polished, romantic treatment.

A puzzling dead end. Is it, though? There is a danger here. It is one thing to try and find a find a place for transgression, one that it indeed ought have within a traditional society. It is whole another to go so far that you are suddenly unable to interpret any portrayal of transgressive act that has less than unambiguously positive results.

I see no puzzle here. What was done was done out of necessity. Sinfjtoli served his purpose, and afterwards the price had to be paid. The end.

These bits are, I fear, what makes me vary of your interpretation. Another case in point would be your celebration of Sigi’s murder of Brethi. Nietzsche, for example, was just as likely to interpret that as a confirmation of his thesis that the most excellent specimen are just as likely to perish out of resentment of their inferiors (plus, in this case we might as well see existing authority and hierarchy reasserting itself by the destruction of exception) which was, of course, his case against evolution via natural selection.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment