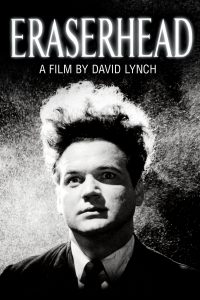

David Lynch’s first movie Eraserhead (1977) combines surrealism, low-budget horror, and black comedy. It rapidly became a staple of the midnight movie circuit and provided endless fodder for coffee-house intellectuals and academic film theorists.

Eraserhead is quite simply a gnostic anti-sex film. The film is premised on a gnostic dualism, which holds that the material world—including sex and childbearing—is fundamentally evil, a prison in which the spirit suffers. The solution to suffering is to free ourselves from the trammels of matter, including sexual desire.

Eraserhead was filmed intermittently, on a shoestring budget, over a period of five years (1972–1977). Although the meaning of the film is self-contained, it is illuminated by some details in Lynch’s biography.

For instance, beginning in 1973, Lynch began his lifetime engagement with Hinduism and Transcendental Meditation. He has reportedly described Eraserhead as his most “spiritual” work.

From 1966 to 1970, while studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art in Philadelphia, Lynch lived in a hellish urban environment like the one seen in Eraserhead.

In 1968, Lynch’s first child, Jennifer, was born while he was still in art school. The pregnancy was unplanned, and Jennifer was born with severely clubbed feet, which required extensive corrective surgeries.

In 1974, Lynch’s marriage broke up, due in part to his infidelity.

Eraserhead opens with a planet in space. Then the sideways face of the main character, Henry Spencer (Jack Nance), floats up from the bottom of the screen in front of the planet (which can be seen through him) and drifts out of the frame. A throbbing sound grows louder and louder as we zoom in on the rough surface of the planet. Then we follow a trench until the screen is utterly dark. Next we see a metal-roofed shack on the surface with a huge hole in its roof. We enter the hole. Inside, we see a man with horribly disfigured skin seated in front of levers. In the background is a cracked and broken window.

We then cut to Henry’s face. His mouth opens, and what looks like a hypertrophied sperm cell comes out. Then the Man in the Planet pulls a lever, and the sperm whooshes out of the frame. Another lever seems to start a huge machine. The camera moves to a pool of water. Then a third lever sends the sperm splashing into the pool. Then we see bubbles and darkness. After that, we move toward a white circle of light, which seems to be glimpsed through a hole in gauze, fringed with hairs or threads. At which point the prologue ends.

The meaning of the prologue becomes clear when we learn a bit later that Henry has fathered a baby with his estranged girlfriend Mary—or at least a hideously deformed something that they think is a baby. Henry’s head and mouth of course are stand-ins for his penis, from which sperm cells actually emerge. The pool of water into which the sperm falls is Mary’s womb. And the movement from darkness to light is the birth of the baby.

The fact that this process is under the control of the so-called Man in the Planet gives it all a sinister cast. Sex and reproduction are material (the planet is a great hunk of matter, pulled into a spherical shape by the force of gravity), mechanical (produced by a huge machine), and directed by the malevolent will of the Man in the Planet, whose deformities emphasize his materiality and who is a kind of Gnostic Demiurge figure, imprisoning the spirit in matter.

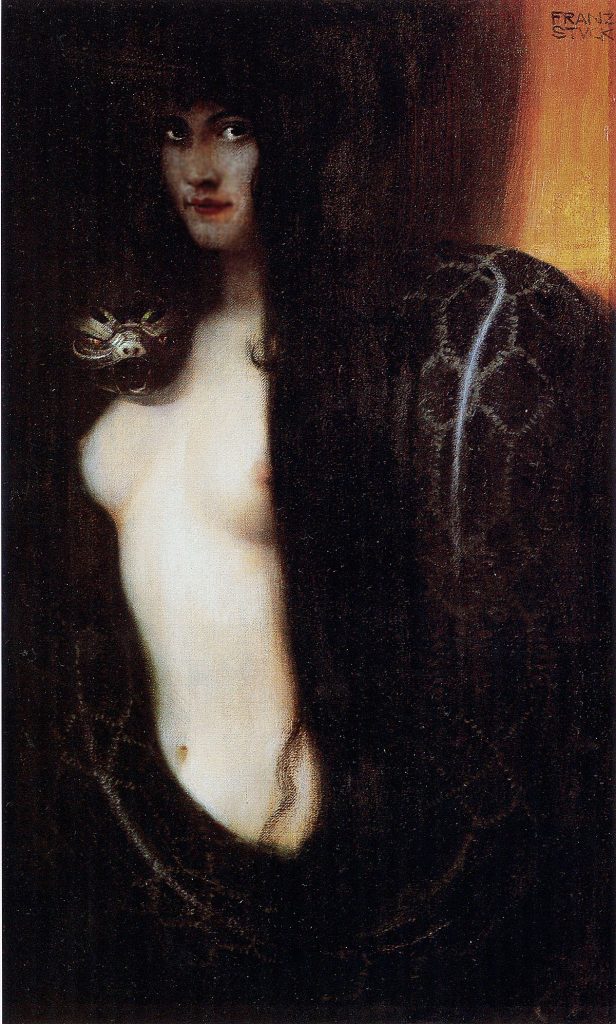

After the prologue, we see Henry’s face, looking back over his shoulder anxiously, as if he is being stalked. He is dressed in a suit with a pocket protector. His hair is teased up in a huge bouffant. He carries a brown paper bag through an industrial hellhole back to his tiny apartment. Before he enters, a beautiful brunette emerges from the apartment across the hall. The brunette is a temptress figure, who in this scene calls to mind Franz von Stuck’s Sin. The brunette tells Henry that someone named Mary called to invite him to dinner at her parents’ house. After an awkward silence, he thanks the woman and goes inside.

Henry’s apartment is a strange place. It is furnished with a table, a record player, a dresser, a tabernacle-like cupboard, a bed, a night stand, and a couple of lamps. What seem to be grass clippings are piled on top of the dresser and on the floor under the radiator. The night stand is decorated with a mound of dirt from which protrudes a denuded branch. A tiny picture of a nuclear mushroom cloud hangs above it. In the top drawer of his dresser, Henry finds a picture of Mary torn in two. Obviously their relationship has been strained.

The next scene, dinner at Mary’s house, is the dark comic high point of the film. The scene begins with Mary’s worried face peering out of the window of her house, which is set in an industrial hellscape with a front yard filled with dead flowers. Like Henry’s apartment, the interior is drab and depressing. There are grass clippings here, too.

Henry’s meeting with Mary’s parents is filled with excruciatingly awkward silences, during which we hear constant mechanical rumbling and hissing, as well as the loud sucking sounds of a litter of nursing puppies. Both Mary and her mother have spastic episodes. Mary’s father Bill has a loud voice, a benumbed arm, and a demented grin frozen on his face. The less said about the chicken, the better.

Then an electrical socket begins sparking and a lamp glows brightly, then burns out, which in Lynch’s cinematic language signifies the presence of the supernatural. The mother then confronts Henry with a very awkward question: “Did you and Mary have sexual intercourse?” The question is followed by some intensely awkward nuzzling from the mother.

The reason she asks is that Mary has had some sort of . . . baby. Mary questions whether it is a baby at all, but the mother insists that it is a baby, a bit premature perhaps, but a baby. She also insists that Henry and Mary get married and raise the child. Henry takes the news by getting a nosebleed. All told, dinner could have gone better.

The next scene takes place a short time later. Henry and Mary are apparently married and living together with the “baby” in Henry’s little room. The “baby” is a grotesque creature. It looks more like a fetal puppy than a human being. Basically, it is a hypertrophied sperm cell with eyes and a mouth. Its body is hidden in bandages. Apparently it has no arms or legs. Mary is becoming increasingly frustrated feeding the “baby,” which writhes, fusses, and spits out its food.

Henry goes to the lobby to check the mail. He finds a tiny package in his mailbox. Furtively, he ducks out to the street to open it, finding a tiny worm inside. He returns, a hopeful smile forming on his face, and lies down on his bed to soak up this scene of domestic bliss, staring into the hissing radiator. When Henry looks into the radiator, a light shines from inside it and an empty stage appears. Henry is pulled back from his reverie by the baby crying. When Mary asks if there is any mail, Henry lies and says no.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

Cut to a dark and stormy night with the baby crying. Henry gets out of bed and places the worm in the tabernacle-like cupboard, which emits a hum that grows louder when Henry opens the doors. Mary lies awake, tense, frustrated, and sleepless, listening to the baby cry. Finally, she loses her cool, leaps out of bed, and screams “Shut up.” Then she dresses and declares she is going back to her parents’ for a good night’s sleep.

Before she departs, Mary kneels at the foot of the bed, peering between the bars of the metal bedframe like a woman in prison, yanking on the bed, causing it to rock and squeak. Is she pantomiming her imprisonment to the baby and the material realm? Is she having another spastic episode? No, she’s just trying to dislodge her suitcase from under the bed. After Mary departs we see the temptress coming down the hall looking wet, tired, and sultry.

On his own, Henry wonders if the baby is sick and decides to take its temperature. The temperature is normal, but suddenly the baby is covered with vomit and hives. Its breathing is labored. So Henry rigs up a vaporizer. At one point he glances at the tabernacle, then moves toward the door, perhaps to check to see if any new worms have arrived in the mail, but the baby starts crying whenever he tries to leave.

Cut to Henry in bed, at the beginning of another sleepless night. The radiator hisses. We hear metallic grinding. Two metal panels part, and we see the stage in the radiator, footlights coming on one after another. Then the Woman in the Radiator appears. She is blonde and wears a white dress. Her face is disfigured with huge round cheeks whose wrinkled texture makes them look like a scrotum. She begins dancing to the organ music that Henry played earlier on his phonograph. Her manner is girlish and demure.

Then sperm cells begin to fall onto the stage. The Woman in the Radiator regards them with childish excitement, but when the organ music stops, she gleefully squishes one beneath her shoe. The music resumes, then stops, whereupon another sperm is crushed. The wind then howls, and the Woman retreats back into the shadows.

Is the Woman in the Radiator’s girlish and demure behavior just an act put on by a dominatrix who excites fetishists by crushing things underfoot? Perhaps. But if so, this is only a minor element of her role. Instead, I see her as an embodiment of asexuality and innocence, a Vestal Virgin whose purity is guarded by deformity, whose role is to crush and reject the deformed products of Henry’s sexuality. If the Man in the Planet represents bondage to matter and sexuality—which is embodied by the hideous and demanding “baby”—the Woman in the Radiator represents freedom from matter and sexuality, as well as the responsibility of parenthood. If the Man in the Planet is the Demiurge, the Woman in the Radiator is Sophia, the divine spiritual/intellectual principle that allows us to be saved from the bondage of the material realm.

Metaphysically, the realm in the radiator is the opposite of the planet in the prologue. The light is the opposite of the darkness of the planet. The stage suggests a realm of imagination, spirit, and freedom, rather than the planet’s realm of matter, gravity, and mechanical compulsion. The music in the radiator contrasts sharply with the mechanical rattle and hum of the planet. If the radiator is heaven, the planet is hell. These contrasts point to a neat gnostic dualism of matter and spirit, bondage and freedom.

When the Woman in the Radiator fades into the shadows, we see Henry tossing and turning in his bed. He wakes up to find that Mary is back, locked in a deep slumber, her face glistening with sweat. Her teeth are clicking together. She rubs one eye, making a gross squishing sound. She is hogging the bed, and Henry tries to force her onto the other side. Then, in horror, he reaches down and finds a sperm cell in the bed. He throws it against the wall, causing it to explode. Then he finds another and another and another. At this point, it is clear that the sperm are coming out of Mary, that she is writhing in the pangs of labor. This is how the “baby” was brought into the world. Mary’s bed hogging, writhing, sweating, teeth chattering, and eye rubbing—as well as the fact that she is unconscious the whole time—emphasize her corporeality and make it thoroughly revolting.

The sperm cells have been splattered against the wall next to the tabernacle cupboard, whose doors now open to reveal the worm, which springs to life and begins squealing. It retreats into the darkness of the cupboard and then appears to be on the surface of the planet, squealing, writhing, doing somersaults, plunging into one hole and then emerging from another. On its last emergence, its end opens up in a vast, all-devouring maw, not unlike one of the sandworms of Arrakis. Mechanical noises grow louder as we plunge inside and then see Henry—apparently from the point of view of an observer in the planet, perhaps the Man in the Planet himself.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Part Four of the Trilogy here.

The worm is sensate flesh, deprived of all higher faculties, capable only of cavorting and suffering on the material plane (the planet) where it is imprisoned, without hope of release. But Henry is more than just a worm. He has higher faculties (Sophia) that might just save him. But he’s due for another test, which the Man in the Planet has dispatched. Cue a knock on the door.

The temptress across the hall has locked herself out of her apartment. It’s late. She wants to spend the night at Henry’s. When the baby begins to cry, Henry stifles it, lest the woman be repelled. Then we see Henry and the woman kissing in his bed—not on it, literally in it. They are sinking into a pool of white liquid in the middle of the bed. She sees the horrifying baby out of the corner of her eye, but continues to kiss and sink. In the end, only her wig is visible, floating on the surface of the white pool. Then we have a shot of white paint separating into two distinct white waves that flee one another. This effect was accomplished by sloshing two waves of white paint together, then reversing the film. The unity between the two has been broken. Coitus interruptus? Then the temptress’ face appears, looking into a sharp, narrow beam of light. Then we see the planet, which seems to force her back into darkness. She is, of course, both an instrument of the planet (a temptress) and a victim of it, since she, too, feels desire.

Then the Woman in the Radiator steps forward from the darkness and begins to sing in a lilting, slightly Southern accent:

In Heaven

Everything is fine

In Heaven

Everything is fine

In Heaven

Everything is fine

You got your good things

And I’ve got mine

In Heaven

Everything is fine

In Heaven

Everything is fine

In Heaven

Everything is fine

You got your good thing

And you’ve got mine

In Heaven

Everything is fine

This is a pretty clear statement of the dualism between the material/sexual/hellish realm represented by the planet and the Man within and the spiritual/asexual/heavenly realm represented by the Woman in the Radiator. Henry then steps onto the stage in the radiator, entering the Woman’s liminal space between hell and heaven—the realm of suffering and the realm of release. They look into one another’s eyes. Smiling, she opens her hands toward him. We heard a loud humming and twice see blinding white light. A glimpse of the stainless void? Then she is gone.

Now we hear the baby crying and, in a flash, see the Man in the Planet. The dead sperm cells blow away. We hear a squeaking sound, and a mound with a dead tree in it is wheeled out onto the stage, an enlarged version of the mound with the dead branch on Henry’s dresser. Henry then steps into what appears to be a witness box, grasping the rail and nervously turning the pipe in its housing. Henry is clearly on trial, torn between the Man in the Planet and the Woman in the Radiator. It’s enough to blow a guy’s head clean off.

So next, Henry’s head blows clean off, while his hands continue to grip and turn the railing. The head of the crying baby emerges from Henry’s neck. Blood begins to pour from the tree and pool up on the floor where Henry’s head has landed. Then his head disappears from the puddle of blood. It falls through the air and lands in an industrial alleyway, where the top of Henry’s skull breaks off. An urchin picks up the head and takes it to a pencil factory. A core sample of Henry’s brain is used to manufacture erasers. A factory worker sharpens a pencil and tests it by drawing, and then erasing, a line. The eraser bits are then just . . . brushed away. It is a bizarre but brilliant image of rampant dehumanization and materialism. Modern man doesn’t just use the whole buffalo. We are the buffalo. Today a man, tomorrow dust in the wind. Eraser dust in the wind.

Fortunately, it was just a terrible dream. Henry awakes and finds the temptress gone. He spends the whole day waiting for her to return. He hears a sound, goes to knock on the temptress’ door, but there is no answer. The baby seems to be laughing at him. Hours pass. He hears the elevator and opens the door. The temptress is there, entering her apartment with a hideous old trick. She looks at Henry disdainfully, seeing his head replaced with the baby’s. Humiliated, Henry shrinks back and closes the door.

Henry feels he has been rejected because of the baby, which fills him with hatred. He goes to the dresser and finds a pair of scissors. He cuts open the baby’s bandages and finds nothing but a pile of entrails. The kid has no body. Obviously, this is not a viable organism. And it is utterly repulsive. And it is ruining Henry’s life. Henry then resolves to kill it, stabbing its pulsating entrails with the scissors. Fluids squirt and then ooze out, followed by enormous amounts of foam. Henry retreats to the other end of his room. The electricity begins surging. Sparks fly out of the sockets. Something uncanny is about to happen. Then we see the head of the baby grown monstrously large, moving around the room, illuminated in the flickering lights. Then everything goes dark, and we hear a thud. Is it the baby? Is it Henry?

Next we see Henry standing in a cloud of eraser dust. (It is the image on the film poster.) Then we see the planet, which explodes. After that, we see the man in the planet, his face in agony, sparks flying from his machinery, which he can no longer control. Finally, the screen is filled with white light as the Woman in the Radiator embraces Henry. Henry has been liberated from the sufferings of the material realm. The end.

But what kind of liberation did Henry achieve? I would argue that it is not liberation through spiritual attainment. Henry has not overcome the desires that cause suffering. He has just killed his baby because it got in the way of satisfying his desire for the temptress across the hall. You can’t get much more sordid than that. Thus I believe Henry’s liberation was achieved simply by death. Hence the cloud of eraser dust, a symbol of the evanescence and ultimate meaninglessness of human life. Henry tried killing the baby, and the baby ended up killing him.

Life is hell. Death is heaven. But there hardly seems to be any sort of moral order governing this arrangement. Heaven certainly does not seem like an appropriate reward for killing one’s child. But maybe heaven isn’t something after death. Maybe it simply is death. And death is simple annihilation, not a passage from one realm to another.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that the message of Eraserhead is pure nihilism, albeit of a spiritual/mystical variety.

It is, however, doubtful that this is David Lynch’s full and final philosophy of life, considering that he ended up fathering four children. When Lynch was in Art School in Philadelphia, his father was so disturbed by some of his artistic experiments that he urged his son not to have children. Just as I’d love to know what Freud’s mother thought about the Oedipus complex, I’d love to know what David Lynch’s kids think about Eraserhead.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Eraserhead%3A%20A%20Gnostic%20Anti-Sex%20Film

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

17 comments

I am not sure what sort of outside academic grounding you would find persuasive. I find academic and professional film criticism on Lynch to be pretty much awful, a real waste of time. I find Lynch’s interviews and autobiography to be very useful, however, and nothing I have found in them contradicts the approach I take here. Lynch is actually a quite intelligible film director, albeit a weird one. He develops a symbolic language and set of themes in Eraserhead and The Elephant Man that run throughout his body of work. Inland Empire and the Twin Peaks reboot were pretty disappointing to me, largely because they are so self-indulgent.

Greg, I’m sure you’re right in thinking it’s more than nightmare images. The whole wouldn’t cohere or stick with you (the way this one does) if there weren’t some overarching fear or regressive morality.

Somewhere, sometime, maybe 40 years ago, Lynch said the setting was inspired by the post-industrial landscape of Philadelphia’s bad parts when he was in in art school. Maybe the Devil’s Pocket or Schuylkill or Fishtown. You wouldn’t be bothered much discovering them in middle-age. But when you come across these places for the first time in your youth, you are astonished by the desolation and the row-houses and the fact that some people actually live and grow up there.

Lost Highway? Piece of cake. Yes, I plan to write about it in the new year. Next stop, though, Wild at Heart. After that Dune.

Oh sweet. I’ll adjust my Netflix ????

Hey, do you like that soiledsinema guy? I think he’s really smart.

Greg, please do . I’m no fan of David Lynch’s but got dragged to see Lost Highway, in any case, by my girlfriend, who IS a David Lynch fan. Maybe I went along because I’m a Bill Pullman fan. I actually became interested in the movie, but never myself reached an interpretation that satisfied me. Looking forward to your take on it.

Bobby,

You may not be a fan now, but if you don’t like the really weird stuff, start at Wild at Heart, which is a simple romance (except Nic. Cage’s performance is wooden until almost the end) and check more.

Lynch is possibly the greatest artist in the U.S.A. Even the film he did for Disney, the Straight Story, is wonderful (another that you may view to tilt your own, it is very quiet and great).

You will never reach a full interpretation.

Such is not possible. Greg’s and Trevor’s are very intesesting, and valid. So are mine, to the small extent that I disagree.

Watch more, if you do not see that Lynch is a great artist of the time, even in stationary art. I don’t know if his style is a copy of others, or vice versa, or that it became a common thing, I tend to think think that Lynch may have originated the stylle, now unfashionable, of putting bits of fur, seeds, a bone, etc. Into boxy shelves.

Mulholland Drive is a very good film. I was pleasantly surprised by Naomi Watts range as an actress. Elephant Man was also a very good film.

Mulholland Drive was a mess. The best things in it were the opening credits, the Jewish landlady with a viper-nose from plastic surgery, and the cleaning man with ‘GENE CLEAN’ on the side of his pick-up truck

It certainly lends itself to alt-right readings, except that the central scene is sapphic. It was supposed to have been a television show in the first place.

Unlike the later Island Umpire (a film so bad that I, even as an early lover of Eraserhead, found to be a dull pile of manure, though I suffered until the end of that, too, in a cinema, hoping that at some stage it would become interesting, never did), Mullholand Drive is never boring, and has many points of ridiculing (((them))).

Well this could be overkill, Trevor. I always read Eraserhead as a brilliant comedy about fears of prospective fatherhood. (Motherhood, not so much; a woman would just kill the mutant, and be done with it. Like Sigourney Weaver; see below.)

Getting connected to low-class in-laws with strange, un-nutritious, faddish dinners. “We’ve got chicken tonight. Strangest damn things. They’re man made. Little damn things. Smaller than my fist. But they’re new!” Wondering how long this 1930s comic-strip austerity is going to continue. No way out.

Alien followed hard up this one’s heels, and I always thought the production design of the gut-monsters was cribbed from Mr and Mrs Henry’s horrible mutant.

Trevor, I was 20 years old and my girlfriend and two of my pals and their girlfriends had our first introduction to David Lynch with when we saw the the Eraserhead in an old run down theater on a street called Western Ave. in Los Angeles around 1978 if my memory isn’t failing me. The opening shot and the rest of the movie has remained a mystery right up until today when you provided me with a great analysis, some 40 years later. Beside the movie, the whole experience in the old theater was crazy. First of all , there was no usher(s). Just the projector guy. Then, after the movie started, some guy wearing a huge coat and sitting behind us, would occasionally pull out a handgun from the inside of the coat and reveal it to anyone who looked at him. The whole theater also reeked of mary juana. We intended to go out for fast food when the movie ended but no one had an appetite left…lol

I have not seen the movie, but it seems to me this is an endorsement for eugenics, not fear of fatherhood. It is the good Christian woman who would love this anomoly no matter what because she has been told to do so and then expect praise because she does so. Birth is graphic and the real fear is that this is what one would get. The alien loves the alien because it is just like her and would fight for it. How can you fight for something so strange?

It’s an interesting break down of the film, but I find myself with the more critical voices on this subject here. I’ve never been persuaded by Lynch artistically. My personal view is he’s something of a rallying point, something of a symbol. He’s someone we are told is sophisticated and offbeat and creative, and that if we are seen to like him then it makes us look sophisticated, unconventional and creative too.

In a world where we are bombarded with a lot of really toxic values and ideas from Hollywood, anything that comes along that is ‘different’ is assumed to be an antidote. But I just don’t find Lynch to be that kind of a creative antidote. Actually I find him to be a capitulation to those bad toxic ideas.

In recent times, the biggest potential issue I have with Lynch – which I will stand to be corrected on if I’m wrong – is he’s not an honest artist. In interviews he claims the most powerful influence on his work was crime-ridden Philadelphia, and he said he was a victim of crime there himself – more than once, if I remember.

I don’t know much about Philadelphia, but it has the same proportion of negroes as whites, and in places blacks are concentrated into 80% of the population.

Who was creating this crime wave there ?

The impression I get is of someone who was a victim of black crime, and the appalling retarded conditions blacks create everywhere but then goes on to make work about how twisted and evil white people are, and that underneath a veneer of white suburban 50’s squeaky clean values beats a heart of sickness and evil.

Sorry but if black crime and disorder and decay really were Lynch’s greatest influences, then that’s just plain dishonest.

He’s not alone in this kind of dishonesty, and it might be semi-forgivable if I found his work as brilliant and inspired as others find it to be, but I don’t, and it feels like he’s transferring the misery and pain created by blacks back onto whites, which whites are then supposed to imbibe as ‘sophisticated’ and ‘offbeat’.

Someone mentioned Mulholland Drive. I made myself to watch this earlier this year. On balance I did not like the movie at all. What Lynch does very well is create these dream-like states, and dream-like transitions from one moment to the next. And he’s very good at that. He’s developed a skill and a cinematic language to do that, but it never seems to be proceeding anywhere. Instead it’s just stuck in this confusion mixed with his boomer aesthetics; giant 50’s microphones against red curtains, midgets and so on. I can almost feel him saying, “Look how cool this is. You agree this is really cool right ?”. And probably some people do agree with him.

My favorite Lynch movie is Dune, because it’s his least typical and I look forward to Trevor’s analysis on that.

Twin Peaks was that sort of thing. The safest place you could ever end up with a flat tire would be rural America. Yet Hollywood would have it be the most dangerous. I’m not surprised that Lynch simply switched from Noggery to an artificial White exurban disintegration.

First issue of Vastarien journal contains great text on Eraserhead as anti-natalist allegory, I suspect that it will be appreciated by folks here.

Since Jeniffer Lynch is mentioned here, and I had not known before that she had bad club feet, I would recommend Boxing Helena, it is worth seeing.

The critics were, IMHO, unfair at the time.

It is quiet but interesting and strange. No wore will I say.

I’m not sure it’s really possible to get to the bottom of this movie definitely, but the analysis here is pretty coherent and surely close to whatever was going on in Lynch’s mind. My take is that the main character had some major screws loose, and the dark surrealism reflects his perspective. Other than that, IMO, the squirrel cheek lady in the radiator seems to represent madness, death, or maybe both.

That said, this is one of the movies I wish I hadn’t watched. It’s been a very long time, but I still shudder thinking about it. This one is a little too “entartente Kunst” for me!

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.