2,255 words

The United States of America and the United Kingdom are both, as you might expect in these transvaluative times, disunited realms. Remaining loyal to Yuri Bezmenov, I believe this disunity is entirely manufactured and intentional, and the main point of interest is the marginally different approaches taken to destabilizing two once-great nations. One major difference in disruptive operations lies in the two countries’ undermining of the power of the police.

Broadly speaking, much of this difference pivots around the First Amendment, to which of course the UK does not have an equivalent. The British establishment has been able to divert many police resources — mostly time — from deterrent or investigative policing to activities which target speech, generally online. The American deep state has no such avenue of distraction, and so the disequilibrium required there is provided by race. That is not to say race does not play a part in the neutering of the British police. Over a quarter of a century before George Floyd died, Britain had its own black martyr in Stephen Lawrence.

Lawrence was infamously murdered by a group of whites in London in 1993. There is no doubt that these men were violent racists, but this case was just what the media had been longing for, just as the American media had prayed for George Floyd. The Lawrence case was absurdly magnified — Lawrence’s mother was elevated to the House of Lords — and led to the McPherson Report, arguably the most damaging piece of ersatz legislation in the history of British law enforcement.

Perhaps the report’s key statement was the first green shoots of something we see today in full bloom: the privileging of the subjective viewpoint over the objective. A racist incident, we were informed in the report, was no longer one legally deemed racist by a court or an arresting officer, but by anyone who deemed it racist. This was not even restricted to the supposed victim, but included third parties. Person A witnesses an altercation between person B, and person C and judges it to be racist? Then it’s racist. This has been the highest card dealt to blacks in Britain. To be able to wave a wand over any incident and transform it into a racist event gave blacks and white liberals that grail of the modern social justice establishment: empowerment.

But in a country where just 3% of the population is black (and half of those seem to work at the BBC), the economics of perceived racism on demand has never had as much supply as it has in the States, with its 13% black population. There were rehearsals for George Floyd — Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown — but once the foundational “white cop kills unarmed black” event was in place, the alliance between race-hustlers and anarcho-tyrannical, anti-white statists could be forged.

One of the many fortune-cookie mottoes to emerge from the Black Lives Matter carnival in the US was “Defund the police,” and if there is a pithier summation of the anarcho-tyrannical crusade, I would put time aside to hear it. That goofy girl band known as “The Squad” cluck about “dismantling” the police, as far as I can gather, because those pesky law-enforcement officers insist on trying to put the perpetrators of criminal acts in jail. As if that wasn’t bad enough, a lot of these miscreants tend to be of the black persuasion, leading to a disproportionately racially-stacked jail population. Note that when liberals use the word “disproportionate” in relation to blacks in jail, they are hoping you won’t notice that due proportion in the context of crime statistics is not supposed to reflect demographics; it’s supposed to reflect crime.

In the UK, a different approach was tried. While urban blacks are the single worst thing about London, the largely white police force tread softly and do not carry a big stick. But, while race is used wherever and whenever possible by the usual suspects, as a diversion of police resources it has been heavily augmented by the politics of “woke.” That the police should “police streets, not tweets” has become an adage, and it is indicative of the absolute polarization of the role of the police, who have shifted from being part of and thus impartially subservient to the public to being a public enemy, attack dogs trained to befriend certain parts of the public (those exhibiting approved concerns) while snapping and snarling to corral the remaining herd. To see the chasm between policing in the UK as it was originally envisaged and what it has been engineered to become, it is necessary to go back almost 200 years.

Sir Robert Peel may have been looking over his shoulder to events in Paris 40 years previously when he introduced the first organized police force in London in 1829, the famous “Peelers.” The “Bow Street Runners” had been set up in 1750 to keep order in London’s streets, but Sir Robert’s was a more coherent and codified institution. Two centuries or so later, it is instructive to compare Peel’s nine principles of policing with today’s “Code of Ethics” issued by London’s Metropolitan Police.

The first stark contrast is that today’s maxims suggest values which would have puzzled Sir Robert, not because they are not manifestly valid, but because of the queerness of having to inform responsible adults of such entry-level moral rigor. Naturally — and before moving on to the differing social contracts instantiated by the two documents — the contrast between moral depth and shallowness in late Georgian England and our current Carolingian times is both illuminating and rather sad. Here is the Metropolitan Police’s third ethical standard, dealing with police impartiality and rather predictably headed “Equality and Diversity”: “I will act with fairness and impartiality. I will not discriminate unlawfully or unfairly.”

Each of the ten standards begins with “I will,” as if this were the Boy Scouts, whereas Peel’s men were addressed as though they existed objectively, part of a wider society and not just within their own inner selves. Compare the above with Peel’s fifth policing principle:

To seek and preserve public favor, not by pandering to public opinion, but by constantly demonstrating absolute impartial service to law, in complete independence of policy, and without regard to the justice or injustice of the substance of individual laws, by ready offering of individual service and friendship to all members of the public without regard to their wealth or social standing, by ready exercise of courtesy and friendly good humor, and by ready offering of individual sacrifice in protecting and preserving life.

I must be going soft, because I find that intensely moving. I don’t imagine a cadet today would last much of the way through an 83-word sentence.

But, like all Sir Robert’s principles, the core tenets were performative and not behavioral, as they are now. The priorities were not patty-cake do’s and don’ts as they have become — “I will be diligent in the exercise of my duties and responsibilities” — but the twin concepts of crime prevention and the social contract between the police and the public.

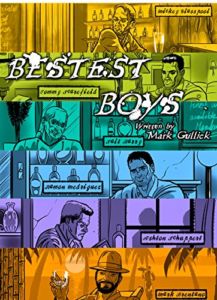

You can buy Mark Gullick’s Bestest Boys here.

In recognition of a now-vanished policing maxim, that a good force does not have a high arrest rate but a low crime rate, Sir Robert’s very first principle is, “To prevent crime and disorder, as an alternative to their repression by military force and severity of legal punishment.”

First and foremost, police officers were a deterrent, a disincentive to would-be criminals to commit crime. The police were both vested with power entrusted to them by their fellow citizens, and visible. Street crime is far less likely to occur on streets which are policed. The modern rise in Britain’s street crime was given an accelerant in 2002, when then-Home Secretary David Blunkett introduced Community Police Support Officers (CPSOs) onto the streets. These “plastic coppers,” as they were uncharitably called, had no powers of arrest and little presence outside their day-glo jackets.

Beat policing had been declining steadily since the 1980s, and CPSOs were the death knell for officer foot-patrols. The contemporary British police have little or no interest in preventing crime unless it is hate crime. Until a short while ago, the role of the police in a crime was to speed there dangerously long after the event, strut about in paramilitary uniforms, give a crime number for the insurers, and go back to the office for hours of deliberately time-wasting paperwork. They don’t even do that now. And, just as Sir Robert’s table of policing begins with the notion of preventative policing, so too its ninth and final principle reads, “To recognize always that the test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder, and not the visible evidence in dealing with them.”

Today’s police also have a test of their efficiency, many of them, but they are composed of racial and gender-based quota systems and targets far removed from the notion of preventing crime.

Preventing crime, you see, betrays an attitude the moderns want expunged, a natural duty of care on the part of the authorities towards those over whom they have authority. This civic duty is the moral foundation of the contract between Sir Robert’s police and the public they represented and served. What was Sir Robert Peel’s opinion of the relationship between his men and their fellows?

The Met’s ethical standards mention the public twice, once informing the reader he must be courteous to them, and again to urge police officers not to act in such a way as to undermine public confidence in the police. Again, if an advisor had suggested to Sir Robert Peel that he ought to tell his officers not to be rude to the public and to behave professionally in front of them, a demotion would have been on the cards.

Five of Sir Robert’s nine principles don’t merely mention the public, but deal specifically with the relationship between them and the police. Public approval is the dominant theme, and this leads to cooperation and the mandate the police require not from politicians, but from their fellow citizens. Approval was just that: a mandate delivered via a social contract as a societal reward for correct performance of duty. “Approval” means something very different now, a confection of ideological orthodoxy and social media applause. Sir Robert’s seventh principle is perhaps the most famous, and again worth quoting in full:

To maintain at all times a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and that the public are the police, the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence. [italics added]

Today, any such social contract has not so much been torn up as heavily redacted. The police no longer belong to the public, as they did under Sir Robert Peel’s vision; they are a part of the provisional wing of globalist government. To ensure they are versed in the new laws (which supersede the Met’s specious ethical two-times table), a British police officer must now have a degree. Given that Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) graduates are unlikely to want to join the police, this means that all new officers will have been pumped full of the neo-Marxist mayonnaise that has body-snatched higher education.

Definitive figures are difficult to come by, as they always are when a matter is of public interest, but there has been a recent memetic repetition of the numbers of solved crimes in the UK being 5%. There was no flurry of denial or press-conference rebuttal from the police, so we might assume these figures are not wildly misplaced. If these figures are feasible, that is a good case for defunding the police entirely. The British police do not have different powers and policies between counties, as America does between states; the funding withdrawal would therefore go straight from the top to the bottom with no regional variations. All that would remain would be a corps of officers prepared to go out on the streets, backed up by a small but competent administrative staff to deal with the paperwork, which would be a fraction of what it is now. It would be hard to claim that British policing had to align with European Union protocols, because I seem to remember a vote to leave the EU which the incumbent government now claim to have effected. A sovereign country can gift itself a sovereign police force. A police force stripped to the bare bones could hardly solve less than 5% of recorded crime.

Any British politician who suggested this would become sainted in the eyes of the British public, particularly those unfortunate enough to live in the big cities. But the political class has no vacancies for that type of social conservatism. Sir Robert Peel’s biographer, Norman Gash, called Sir Robert “one of the greatest public servants in British history.” There would be no place for him or his Georgian values in London today.

One of the key pseudo-methodologies used by the woke postmoderns is to look backwards and apply to the past today’s supposed moral values, which are in fact a psychologically unstable wish-list made up on the hoof by bigoted know-nothings. The only counter-stratagem — and it should come naturally to conservatives — is to take moral exemplars from the past and attempt to reimpose their values on today’s tawdry shambles. Sir Robert, I’ll quote the famous line from British sea-side postcards: Wish you were here.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

- Fifth, Paywall members will have access to the Counter-Currents Telegram group.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Defund%20the%20%28British%29%20Police%3A%20Peeland%238217%3Bs%20Nine%20Principles

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

A Family with the Wrong Members in Control: Orwell’s England

-

Katharine the Great: The State of British Education

-

Police, in the Real World

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

Comment Georges Floyd a détruit la ville de Minneapolis

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 1

-

The Worst Week Yet: March 31-April 6, 2024

-

There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack

2 comments

Every one may remark what a hope animates the eyes of any circle, when it is reported or even confidently asserted, that Sir Robert Peel has in his mind privately resolved to go, one day, into that stable of King Augeas, which appalls human hearts, so rich is it, high-piled with the droppings of two hundred years; and Hercules-like to load a thousand night-wagons from it, and turn running water into it, and swash and shovel at it, and never leave it till the antique pavement, and real basis of the matter, show itself clean again!

Thomas Carlyle, “Downing Street”, 1 April 1850.

That’s wonderful, thank you.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.