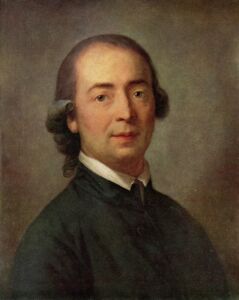

Remembering Johann Gottfried von Herder (August 25, 1744–December 18, 1803)

Martin LichtmeszThe following is extracted from the book Ethnopluralismus: Kritik und Verteidigung and translated by F. Roger Devlin.

Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744-1803) was one of the outstanding figures of Weimar Classicism, even if spiritually to be counted among the Romantics. He is the most important and genuine ancestor of ethnopluralism. Heinrich Heine wrote of him:

Herder considered all humanity as a great harp in the hands of the great Master; each nation seemed to him one string of this enormous harp, tuned in a particular way, and he understood the universal harmony of their various sounds.

Herder is so often connected with the concept of national spirit [Volksgeist] that one is surprised to learn that the expression does not appear in his writings — but at least Geist der Völker [spirit of the nations/peoples] can be found (comparable to Montesquieu’s esprit général or Voltaire’s esprit des nations) in his Essay on World History and the Mores and Spirit of the Nations.

Unlike Hegel, he does not look for a great divine plan which fits in with a rational final purpose. But he is concerned with a universal image spanning humanity and the world. He postulates a unity of “human nature” from which he deduces a brotherhood of all nations on Earth. But Herder is no systematic thinker looking for an airtight universal theory. He would rather tell a universal story: He is enchanted by the “great living portrait of ways of life, customs, needs, peculiarities of country and climate” of the nations. Regarding the wealth of the divine creation, he is nearly at a loss for words: “if only the universal ocean of nations, ages, and lands might be encompassed in a single view, feeling, word!”

His four-volume work Ideas for a Philosophy of the History of Humanity begins in space, with a view of the “dwelling place of the human race” and the great “workshop for the organization of the most varied beings”: the Earth, on which Herder zooms in to discover and make visible ever more details and levels of composition: from geography and climate to the Earth’s animal and plant worlds; from zoology to anthropology by way of art, science, religion, history, tradition, and language; to the organization of the nations. What is the purpose or meaning of the variety of forms of human existence? Herder does not pretend to know as much as Hegel. What brings the spirits of the nations to expression, so Herder suspects, is “humanity”:

I wish that I could comprehend in the word humanity everything I have so far said concerning man’s noble formation to reason and freedom, to finer thought and action, to the most delicate as well as the strongest health, to the fulfillment and mastery of the Earth: for man has no nobler word for his vocation than himself [i.e., humanity], in which the image of the Creator of our Earth as here made visible has been impressed and lives on.

Because a single form of humanity and a single region could not comprehend it, it was divided into a thousand forms; and it wanders, an eternal Proteus, through all parts of the world and all centuries. And as it wanders and changes, it is not the greater virtue or “happiness” of the individual it strives after, and nevertheless a plan of striving forward becomes visible: such is my great theme!

Thus he is a thorough “enthusiast for humanity,” and hence in a certain sense a universalist, but he looks for this general human character in concrete national manifestations. In this he resembles De Maistre, whose image of man is, however, dark and pessimistic. And contrary to the great representative of the Counter-Enlightenment, Herder thinks of culture from below, from the point of view of the simple people, which seems to him a “natural” quantity. Herder loves the little people and the little nations, seeing in their nature and activity something primal, poetic, earth-bound. He tries to detect the “national secret” of small peoples in their folktales, sagas, and myths. According to Herder, warlike nations bring forth warlike songs about their deeds while “milder provinces tell milder tales”; nations with warmer passions sing primarily of these. Herder is thus also one of the fathers of differential national psychology.

One of his primary sources for detecting the character of nations is the “folk song,” a concept he coined. His influential collection Voices of the Nations in Songs contains, along with traditional German songs, translations from English, French, Lithuanian, Estonian, Spanish, Greek, old Scandinavian, Scottish, Italian, Sicilian, Tatar, “monk Latin,” and even “Lapplandish.” Herder thus promoted not only the national feeling of his German fellow-countrymen but, with his chapter on the Slavs from the Ideas, significantly influenced pan-Slavism, something he is still blamed for by today’s remnants of German folkish groups. Herder arranged nations in no hierarchy, but saw them as equally valuable expressions of human plurality. “Each nation has the center of its own well-being in itself, as each sphere has its center of gravity within itself,” and so could only be happy through being what it is and not in the imitation of foreign ways of living.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s From Plato to Postmodernism here

Herder does not assume that a nation is static and unchangeable, or that it cannot accept influences from outside. If it is firm enough in its own nature, it will be able to make use of what is foreign. “The Greeks assimilated as much from the Egyptians and the Romans from the Greeks as they needed for themselves: they were satisfied with this, and the rest fell away and was not sought out!”

Herder was a nationalist of all nations, but a nation is for him anything but a great civilizational construct; on the contrary, it is “a great unweeded garden full of both valuable plants and weeds.” Who would want to “break a spear against other nations” regarding this sprawling “collection point of foolishness and mistakes, as well as of excellences and virtues?” Like individuals and generations, nations should learn from one another “until finally all have mastered the great lesson that no people is the only chosen people of God; the truth must be sought by all; the garden of the common best must be constructed by all.” Therefore “no nation of Europe may close itself off from the others and foolishly say: with me alone dwells all wisdom.” He constantly warns against Eurocentric conceitedness:

Foolishly proud would be the pretention that the residents of all parts of the world must be Europeans in order to live happily; for would we ourselves have become what we are outside Europe? So the boast of certain European vulgarians is vain when they set themselves above all parts of the world as regards enlightenment, art, and science.

In his chapter about African nations, Herder tries to imagine how an African might look at Europeans:

With the same right as we hold the Negro for a cursed son of Ham and the likeness of a fiend, he can declare his cruel robbers albinos and white devils who only through a weakness of nature became so degenerate, just as many animals degenerate into whiteness near the North Pole. “I, the black man,” he might say, “am the original man. The source of all life, the Sun, has drenched me most fully; everywhere around me he has worked most deeply. Look at my land rich in gold, in fruit, in trees reaching to the skies, in powerful animals! All elements about me swarm with life, and I have become the middle point of it!”

This is classic ethnopluralism: the attempt to understand the perspective of the other, always with the awareness that we can never get outside our own skin when we contemplate and judge other nations. In another place, Herder praises the positive aspect of “prejudice”:

Prejudice is good in its own time: for it makes happy. It condenses nations toward their middle point, fastens them more strongly to their root, makes them more flourishing according to their kind, more ardent and therefore more blessed in their inclinations and goals. In this regard, the most ignorant, most prejudiced nation is often the first: the age of foreign journeys and wanderings is often already sickness, unhealthy fullness, an intimation of death!

To have no prejudices is for him already a sign of paralyzed vitality. Xenophilia can mean a flight from oneself, while no tribe can exist, let along be “happy,” without a certain isolation from without. This passage from the ninth book of the Ideas sounds downright anti-globalist and anti-imperialistic:

Nature raises families; so the natural state is a people with a national character. Nothing seems more obviously foreign to the purpose of government than the unnatural enlargement of states, the wild mixture of human kinds and nations beneath a single scepter.

Likewise so is this quote from Letters on the Promotion of Humanity, which makes clear that he does not imagine the national garden as a multicultural chaos, but pleads for distinct gardens in which each people can remain at home:

The variety of languages, customs, inclinations, and ways of life should bar the arrogant concatenation of peoples, a dam against foreign flooding: for the world’s householder intended, for the security of the whole, that each nation receive its own imprint. Nations should live next to one another, not press upon one another.

Ideally,

everyone will love his country, his customs, his language, his wife, his children not because they are the best in the world but because they are his, and in them he loves himself and his own efforts.

Rüdiger Safranski summarizes Herder’s image of the world as follows:

Herder’s patriotism was democratic and assumed a variety of cultures. Many paths lead — where? In any case, not to the rule of one people over others, but rather (according to Herder’s ideal) to a varied garden in which national cultures develop their best possibilities separately, but with mutual exchange and cross-fertilization.

Remembering%20Johann%20Gottfried%20von%20Herder%20%28August%2025%2C%201744%E2%80%93December%2018%2C%201803%29

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.

Related

-

Earth Day Special

-

Popcult Humor from Wilmot Robertson: Remembering Wilmot Robertson (April 16, 1915–July 8, 2005)

-

Remembering Dominique Venner (April 16, 1935–May 21, 2013)

-

Remembering Jonathan Bowden (April 12, 1962–March 29, 2012)

-

Remembering Emil Cioran (April 8, 1911–June 20, 1995)

-

The Man of the Twentieth Century: Remembering Ernst Jünger (March 29, 1895–February 17, 1998)

-

The Power of Myth: Remembering Joseph Campbell (March 26, 1904–October 30, 1987)

-

Remembering Flannery O’Connor (March 25, 1925–August 4, 1964)

2 comments

Thank you for your informative essay. The first I’ve heard of Herder, I’ll be looking closer at him and his writings/ideas. Interesting guy!

Perhaps the saying: “A nationalist respects other nations, yet loves his own” is an extreme condensation of what Herder had in mind. That people were conscious of their home country and jealous of others before Herder brought the notion of ‘Volk’ as it is understood now, at least was understood until recently, before malevolent sophistry dissolved this idea into something to disapprove of by the sophisticates who aspire towards inclusion in the current high society, emerged from reading the book “The Calculus Wars”, a few years ago, where I learned that Newton was very jealous of non-English people to have had ideas about infinitesimal calculus.

Herder was apparently an idealist of high order, contemporary of Lessing with his Three-ring parable. He would have idealized national characteristics, which on the one side could have been stretched to the extreme of chauvinism, and on the other side have led to a well-defined national art. The realization of the possibilities of a concept of the world differing from one people to another was a great inspiration and was in my opinion one reason for the sudden multiplication in the production of music, of the scientific writings, of establishing new fields of study, of inventions. Herder seems to have said what everyone knew but was not conscious of.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.