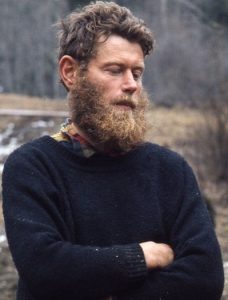

Remembering Pentti Linkola (December 7, 1932-April 5, 2020)

Timo HännikäinenCzech version here

Like other Nordic countries, Finland has a strong conformist mentality. The Law of Jante is in force to keep too headstrong or conflict-seeking individuals leashed. In this respect, it is strange that one of the modern Finnish cultural icons is a character as extreme as Pentti Linkola. Throughout his career as a public intellectual, Linkola, who died on April 5th, 2020, aged 87, said things that would have made anyone else a social outcast or even a criminal. He described German National Socialism as “a magnificent philosophy,” openly rejoiced the 9/11 attacks, praised the Baader-Meinhof Group, and said that the global human population should be reduced by means of bacteriological warfare.

Still, many of even those who thought Linkola was a madman or a brutal fascist esteemed his ascetic way of life and masterful literary style, considering him a remarkable personality. Every year, some major newspaper or periodical published an extensive interview of him. In 2017, Riitta Kylänpää’s biography of Linkola won the Finlandia literary prize for non-fiction. Appreciation of Linkola often crossed traditional political frontlines.

I became a huge fan of Linkola in my twenties, and I would perhaps never have become interested in environmentalism without reading his essays. His writing style was deeply personal, fuelled by aggression and sorrow, and his favoring of long sentences resembled rather classical Finnish authors like Aleksis Kivi and Joel Lehtonen rather than mainstream literary modernism.

Later I met Linkola several times in person, although I cannot say I knew him well. The first time was in autumn of 2002, when I went to his fisherman’s cabin in Valkeakoski to interview him for a literary magazine. Linkola told me about his aesthetic preferences. He said that in Finnish literature he liked the classics most, but he also read widely contemporary prose. He wondered why “two masterpieces of world art,” Aleksis Kivi’s Seven Brothers and the symphonies of Sibelius, were created in Finland, even though Finland is “a remarkably stupid nation.” Of his stylistic ideals he said something very agreeable:

I think that good prose style should at least be lucid. And it is a difficult goal, depending on the subject, of course. If a cleaning lady finds ripped sheets in the wastepaper basket, she should at least understand what the writer has meant, no matter what she thinks of it. And style should not be dryish, one should avoid professional jargon, and if there are Finnish equivalents for words, one should use them, not expressions derived from Latin and other foreign languages. I have tried to make my style clear and colorful on the one hand, but also avoid clichés and too original expressions. There should be some kind of balance; one should use rich language but not subvert the constructions of language. It is terribly demanding indeed, and one can never fully succeed.

The Linkola I knew was a cultivated, polite, and self-ironic man. He had a dry sense of humor. When I met him at the Helsinki Book Fair a few years ago, I asked: “Pentti, how are you?” and he answered: “Well, worse than yesterday, better than tomorrow.” Sometimes he telephoned me to discuss some newspaper article or book. During one of his calls, Linkola, 84 years old at that time, complained that his feet, which had always been the strongest part of his body, had started to fail him. “Nowadays I can walk only a couple of kilometers nonstop, and then I already must rest at the side of the road.”

You can buy And Time Rolls On: The Savitri Devi Interviews here.

It is not very difficult to understand why the Dissident Right appreciated Linkola. He criticized modernization, humanism, and globalism in a way that was charming even in its most extreme and provocative forms. Like many luminous figures of all eras, Linkola was a son of an impoverished upper-class family, and his hatred towards the vulgarity of the modern age stemmed from his family background. He was no politician and had no mass movement behind him, so he was immune to all forms of political correctness. Unlike most other thinkers of the Green Movement, he always recognized the ecologically and culturally disastrous effects of mass immigration. He said to the author Eero Alén: “Helsinki has become a Negro city. Everywhere you go, you see Negroes. That kind of Helsinki is no true Helsinki for me.”

Linkola did not consider the nation a value as such, but his thinking did have some nationalist elements. In his book Unelmat paremmasta maailmasta (Dreams of a Better World, 1971) he wrote:

I think that a true brotherhood of men requires same kind of environment and conditions, and also some concord in view of life. A Swedish or Russian environmentalist is surely closer to me than a Finnish economist or engineer, but a Brazilian environmentalist would probably not be. A man who has never fought against snow and frost could hardly be truly close to me.

Linkola’s pessimistic and heroic attitude is also something that men of the Right understand instinctively. The Dissident Right is constantly looking for those who are pure in spirit and fight for their cause till the end even if it is hopelessly lost. Linkola thought that stopping the ecocatastrophe was extremely unlikely and that his own impact on the course of events was virtually nonexistent. Still, he never stopped fighting, because effort, even a futile one, makes life meaningful. Throwing in the towel is the deed of an honorless man.

It is harder to grasp why the appreciation for Linkola was so wide in Finnish society. One often hears the sentence “I appreciate Linkola because he practices what he preaches,” but I think that is a cliché. No one fully practices what he preaches, because life itself is a kind of compromise. Of course, one should avoid gross contradictions between words and deeds, but especially in the case of livelihood and survival, everyone makes exceptions.

Linkola, who rejected most comforts of modern society, was probably more consistent than most of us. Certainly, he was more consistent than a typical Green Party parliamentarian who never leaves Helsinki except when he flies to an international climate congress. But like his friend and associate Eero Paloheimo said, Linkola was not admired because of his consistency, but because he suffered. For Linkola, environmental disasters were not abstract administrative problems but personal catastrophes. He was a passionate biophile, for whom the frail bond between man and Earth was a deeply intimate and tragic thing. Unlike so many others, he refused to abandon his most genuine source of joy. This refusal led him to the fringes of society and made his life a one-man demonstration. It also made Linkola a more interesting figure than most of his admirers and enemies.

* * *

I wish to draw your attention to the following works on this site:

By Linkola:

- “Bull’s Eye“

- “Citations choisies” (in French)

- “Humanflood“

About Linkola:

- Diord Fionn reviews Pentti Linkola’s Can Life Prevail?

- Derek Hawthorne, “In Praise of Pentti Linkola“

- Greg Johnson, Interview on Eco-Fascism (Translations: Czech, French)

Related to or referencing Linkola:

- Chad Crowley, “Towards a New European Palingenesis“

- Robert Stark interviews Greg Johnson on Eco-Fascism

- William de Vere, “Ecofascism Resurgent“

Finally, I recommend “The Ecosins of Pentti Linkola,” a short documentary/interview on YouTube which has English subtitles.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Remembering%20Pentti%20Linkola%20%28December%207%2C%201932-April%205%2C%202020%29

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Popcult Humor from Wilmot Robertson: Remembering Wilmot Robertson (April 16, 1915–July 8, 2005)

-

Remembering Dominique Venner (April 16, 1935–May 21, 2013)

-

Remembering Jonathan Bowden (April 12, 1962–March 29, 2012)

-

Remembering Emil Cioran (April 8, 1911–June 20, 1995)

-

The Man of the Twentieth Century: Remembering Ernst Jünger (March 29, 1895–February 17, 1998)

-

The Power of Myth: Remembering Joseph Campbell (March 26, 1904–October 30, 1987)

-

Remembering Flannery O’Connor (March 25, 1925–August 4, 1964)

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 576: Greg Johnson & Morgoth on Dune: Part Two

11 comments

I think the man is celebrated because he advocated for the death of billions of his own kind. The only White ecologist that I have encountered who was not an extreme anti-White misanthrope is Aldo Leopold. That the right wing of White Identity Nationalism can be bamboozled into valorizing genocidal misanthropes like Linkola is just sad.

Do you consider Madison Grant to be an “extreme anti-White misanthrope” or do you not consider him to be an ecologist?

I don’t know Madison Grant’s complete works enough to know the answer to that question. Based upon what I’ve read of his work, he didn’t sound like a ‘the human race is a plague and needs to be destroyed’ kind of person or an advocate for actively reducing the number of Whites on the planet.

Ok. I just wanted to clarify. When you said that Aldo Leopold was the “only” ecologist to not be an anti-White misanthrope, I thought that you meant Madison Grant was (by implication) an anti-White misanthrope, and that sounded a bit off to me. You had me wondering if there was something about him you knew that I didn’t that would lead you to believe that.

The operative part of that sentence – ‘that I have encountered ‘ – apparently wasn’t clear.

That’s my impression exactly. I don’t want to “glass” the planet, but I don’t get these LARPy Luddites.

🙂

Linkola did not advocate for reducing the number of whites; he advocated for reducing the number of human beings in general, which is indeed crucial if we are to survive. He had no anti-white animus. As this very essay points out, if any of you had bothered to read it, he said that anti-white immigration was a bad thing. Don’t find problems where there aren’t any.

If you reduce the number of ‘human beings in general’ you will, by extension, reduce the number of White human beings. It’s basic logic. Opposing anti-White immigration is not a huge plus for a guy who thinks that Whites should be exterminated along with the rest of ‘humanity’. It’s just a casual preference when compared to his deeper convictions that White human beings must die great numbers. The White Right is entirely schizophenic when it comes to population. On one side, you have the ‘We must have more White babies’ and on the other you have ‘We must reduce the population!’ Linkola is a universal misanthrope. A true Enlightenment figure. He’s admired by the White Right because they think he’s not talking about exterminating White people along with everyone else. However, if he was some darkie who lived in a hut in Africa and said the exact same things, the White Right be a suspicious as hell as to the guy’s intentions. I stopped thinking there was a universal ‘humanity’ a while ago. There are only races. And anyone who advocates for the ‘reducing the number’ of humans in general is not a friend of the White race. No matter how many nice things they say about the NSDAP.

The numbers in all races must be largely reduced, including whites. Anyone who doesn’t see that is only focusing on one aspect of the problems we face.

I am going to focus on Whites because that’s what a White Nationalist does. Everything comes down to whether a policy is good for Whites or not. There are no universal values, only implacable laws. And one of those ‘laws’ is: If you don’t take your own side, you will be destroyed.

Linkola thinks that if you take everyone’s side then everyone will gain – and suffer – equally.

But that’s only true if you think the 60 IQ African Black is the equal to the 110 IQ European-North American White.

Linkola seems to think that’s true.

I don’t think that’s true.

Do you?

Besides, the problem of excessive population growth appears to be in the process of solving itself.

https://imperiumpress.substack.com/p/the-third-world-is-going-to-cop-it-b9e

We cannot think of these problems in isolation from one another. The idea that the “white race,” however one chooses to define that, can just somehow detach from the rest of the world and go its own way is a fantasy.

In 1800 there were not, and there had never been, a billion people living on the planet. In 1900 it is estimated that there were 1.6 billion people. Today there’s nearly eight billion. We’re on course to be at over ten billion by 2100. We’re no longer living in a world where nature keeps everything in balance. Either we do it ourselves, or we’ll have a mass mortality event at some point.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment