The Cold War Preacher: A Look at the Career of Billy James Hargis

Morris van de CampIn the middle 1960s, the geo-strategic position of the United States was not unlike what it is today: America and Western Europe were locked in a confrontation that was economic, military, and ideological with the Soviet Union (i.e., Russia) and communist China.

Up until that point, the communist world had moved from success to success, in part because of considerable American support. This support was fueled by a large domestic element that was sympathetic to communism within the United States — especially in the New Deal Democrats, who had positions and influence in the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and subsequent Democratic administrations.

It really wasn’t until the Korean War that the broader American public started to recognize the issue and the political Right began to make considerable gains. Richard Nixon, Joseph McCarthy, George Lincoln Rockwell, Willis Carto, and others were energized by the threat of global communism.

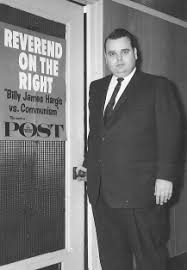

One of those people who was energized by the threat of communism was Billy James Hargis. Hargis was a high-end backwoods preacher born in Texarkana, Texas in 1925. His adoptive father had been a truck driver for the Hunter Transfer Company, while his adoptive mother was arthritic. Hargis was very close to his mother and he had no brothers or sisters. His first job was as a soda jerk at the Carroll Drugstore, where he made $2.50 per week making chili dogs and ice cream drinks. He served, among others, Senator Shepherd of Texas, Roy Rogers, and Congressman Wright Patman.

He didn’t serve in the Second World War, instead working as an architect’s assistant and building inspector for a government agency that built housing for defense industry workers. Hargis admitted in the 1960s that he hadn’t been entirely sure of what he was doing as a building inspector, having been thrown into the job. He was ordained as a Disciples of Christ minister as a teenager, even before he completed his studies at the Ozark Bible College.

Hargis’ lack of education was limiting. In an interview with Tomorrow with Tom Snyder, he expressed his frustration on that count, saying, “I’m not qualified to run for any political office. I’ve got a year-and-a-half of college! I was a poor kid out of East Texas and I’ve got a year-and-a half-of college. All of that’s Bible College.”

His first job as a preacher ended badly. At the Christian Church in Ozark, Arkansas, he denounced a local school principal who was having an affair from the pulpit of his church, as well as some the deacons, and was asked to leave shortly thereafter. He then headed to Bentonville, Arkansas, where he met Dr. F. W. Strong, President of the Ozark Bible College, and as a result of that connection, he received a pastorate in Sallisaw, Oklahoma for two years, and then in Granby, Missouri for two years after that.

He was next assigned to the First Christian Church in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, which was having internal troubles. He was hired to be a neutralizing force within the warring congregation. It worked. He was no longer the callow teenager denouncing others based on rumors, but instead united the church’s factions. As a result, his church grew in membership.

While preaching as a guest minister in Ohio, the organist played a wrong note. As he looked over at the organist, his eyes first fell upon Betty Jane Secrest of Sciotoville, Ohio. Shortly thereafter, he married her. Betty Jane’s family mostly originated from Virginia, and they went on to have five children together.

At the age of 24, he felt that he needed to be more than just a comfortable pastor in Oklahoma and decided to become an anti-communist activist as well. There were plenty of people who attempted to dissuade him from this, but he persevered.

Bible Balloons

Hargis began travelling in the anti-communist fundamentalist religious circuit as a radio preacher, and then in 1953 he hit upon the idea to travel to Europe to see the Iron Curtain for himself. While there, he wrote seven letters for his supporters describing his experiences.

These sorts of letters are not unusual for American ministers traveling in Europe. Hargis’ letters mostly focused on visiting the various places that had been influential in the Protestant Reformation. He wrote favorably about Edinburgh, Scotland, where John Knox had preached, and Geneva, where John Calvin had preached. He did not like Paris and London. He disliked Paris for the same reasons most Americans do, and he found the Londoners to be anti-American. The resentments felt by Londoners over American servicemen being “overpaid, oversexed, and over here” were still very much alive in 1953.

Hargis didn’t visit the Wittenberg Cathedral, where Martin Luther had nailed his 95 Theses, since Wittenberg was on the other side of the Iron Curtain. But since getting his ideas across the Iron Curtain was the ultimate aim of his trip, he decided to launch hydrogen-filled balloons carrying Bible verses translated into various Eastern European languages from West Germany into the communist-held east.

The balloon launch showed Hargis’ ability to organize people to execute a technically-sophisticated event. He first had to assemble the volunteers, who were mostly refugees from Silesia, and then get the materials to them, as well as selecting the balloons that would travel the furthest. He then had to monitor the winds so that the balloons would head in the right direction, while coordinating all of these efforts with the local government authorities. The balloon launch generated considerable favorable publicity for Hargis.

After Hargis’ balloon launch, the practice of sending religious material into Soviet-controlled Europe became “a thing.” In 1955, a Dutchman named Andrew van der Bijl became a household name in Evangelical Protestant circles in both Europe and America after he smuggled Bibles to Christians in Poland and other communist-controlled lands.

It is unlikely that any communists in Eastern Europe changed their minds after coming across one of Hargis’ balloons. Nevertheless, the event did help to bring Christians and anti-communists in North America and Europe together, and the affair gave them valuable experience in cooperation. One could therefore say that the balloon launch was an instrument for changing domestic minds rather than foreign ones.

Apogee

The high point of Hargis’ career came during the Kennedy administration and immediately afterwards. President Kennedy was staunchly anti-communist, but a large part of his political base consisted of anti-anti-communists as well as liberals sympathetic to communism. Kennedy’s administration likewise had a large share of ethnonationalist Jews who were sympathetic to the Soviet Union and hyper-loyal to Israel, but Hargis didn’t take on the JQ directly. He saw the Anti-Defamation League as only one of his many political enemies in his various writings.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s New Right vs. Old Right here

Throughout his career, Hargis was very much aware of what was happening in the Cold War and how Soviet strategy was shifting. He also knew the histories of every communist country, including those such as Yugoslavia and Albania, which were only partially aligned with the Soviet Union.

Hargis also kept abreast of the American government’s official counter-espionage and anti-communist efforts. When President Kennedy was killed by an antifa assassin acting on his own in Dallas, Hargis recognized the event for what it was. Nevertheless, nice, sensitive liberals who had loved Kennedy became immersed in conspiracy theories and other false leads, causing them to misread data on other matters for decades thereafter.

Hargis pointed out that the media was so set on blaming the Right or JFK’s murder that they damaged their credibility. In one of his books, he quoted Hilaire du-Berrier as follows:

Out of the Dallas crucible came facts which realistic America must face: for meanness, viciousness, dishonesty, and absence of all sense of honor, the groups referred to as the American Right are no match for the organized, entrenched, and internationally-supported Left lined up against them. Radio, TV, the press, government agencies, and militant politicians took a position against America’s interests and for the Left. Your correspondent was in Dallas when [JFK’s assassination] happened. The first announcement of the killing was coming over the air when the first threatening telephone call reached the home of General Edwin A. Walker, who also lives in Dallas. A woman’s voice said, “We’ll get you, you bastards.” For three days and nights the telephone threats and insults continued. Other known conservatives were likewise menaced . . .[1]

According to a 2013 PBS documentary about Walter Cronkite’s role in reporting JFK’s assassination, a large segment of the public began to mistrust the American press in the wake of the event. The documentary surmised that by watching the news get made in real time, the magic was lost. That assessment is correct for the most part, but the key factor in watching the news get made was that the media’s liberal bias was put on display for all to see. The reporters of the time were so submerged in their biases that they failed to fully grasp the fact that Kennedy had been killed by an avowed Marxist-Leninist rather than by a disgruntled Right-winger.

Operation Midnight Ride

By early 1963, Hargis had a considerable following on the radio and his anti-communist message was making inroads across American society. He eventually allied himself with Major General Edwin Walker. General Walker and his information officer, Major Archibald Roberts, had been fired by the Kennedy administration for distributing anti-communist literature that had frightened anti-anti-communists who were influential JFK supporters. Walker initially referred to this metapolitical campaign as the Pro-Blue program.

The tour later came to be called Operation Midnight Ride. Hargis would focus on the internal threat to America posed by communism while Walker focused on the international scene. Hargis, for his part, was a good orator. He was a “jump and bawl” sort of preacher of the sort that is common in the greater Appalachian region. Walker’s speeches were wooden and less entertaining by contrast.

In retrospect, it is clear that Operation Midnight Ride was the apogee of Hargis’ career. After that tour, he established the American Christian College in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1966. Rumors circulated that Hargis was having sex with young adults from the college’s choir. The scandal broke in 1976 and the college folded as a result. I believe that the charges against Hargis were true. All churches are sexually-charged places, and it is not unusual for church leaders to fall prey to sexual temptation. Hargis’ story is a good reminder that sexually reckless behavior causes any project in which the perpetrator is involved to always be only a single conversation away from disaster.

After the scandal toppled Hargis, he suffered a stroke and was bedridden for a year. When he recovered, he’d gained fifty pounds on an already heavy body. Hargis’ weight was an issue throughout his career, making him an easy target for mockery by his enemies. He could have slimmed down, but chose not to.

Hargis published books and other materials until his son took over his diminished ministry, but he never really recovered. He argued that Christians “shoot their wounded,” but was misreading of the situation. A top-level minister with a national following is like a baseball player in the Major Leagues: If he screws up enough, he is simply replaced, not rehabilitated.

A Critique of Hargis’ Career

One could say that Hargis’s career was ultimately a failure, but it was not entirely so. His “jump and bawl” fundamentalist style of Bible-centered Christianity doesn’t have much of an effect on most Europeans or even many Americans, but it does work in greater Appalachia.

This was part of the reason for his initial success. It was never a foregone conclusion that Middle America was going to reject communism. The communists had sympathetic followers in Kentucky and West Virginia in the first half of the twentieth century. In the 1920s, labor agitation in these areas was strident and quite Leftist in orientation. There was even a gun battle at Blair Mountain involving a labor dispute, where striking miners wore red scarves.

Hargis was instrumental in separating large parts of greater Christianity from communism in particular and radical Leftism more generally. In Britain, many Protestants were highly sympathetic to radical Leftism and communist-style command economies. Correlli Barnett had criticized the British Left’s perverted Protestantism when he wrote:

‘Nationalisation’ was an emotive symbol, a slogan, rather than a thoroughly worked-out practical scheme based on a grasp of the technology and organization of modern industrial processes. ‘Nationalisation’ indeed, as the Labour Party understood it in its pseudo-religious fashion in the 1920s and 1930s, was a secularized Wesleyan conversion. Upon industry, in its sinful state of exploitation and decrepitude, the act of nationalization would, like baptism, confer a state of grace, and instantly the convert would enter upon a new life.[2]

Hargis helped the United States to avoid the poor economic decisions made by the British that contributed to decades of post-war stagnation in the United Kingdom.

Hargis also pointed out media bias throughout his career. His 1980 book about the media’s sensationalism, monopolization, and dishonesty was radical for its time, even if this is now universally known.[3] Indeed, Right-wing activists of various stripes are creating their own media outlets, and Americans can now get their information from many different sources.

Hargis’ career was only partially successful regarding what one could call “arguments between monks.” Theological disputes have little impact on most real-world issues, but those where they do set the tone for the rest of society. Hargis pointed out that many Christian organizations had gone far to the Left and were tolerating things that were problematic. For example, Baptists encouraged their members to read James Baldwin, a sub-Saharan activist who promoted homosexuality. Hargis likewise predicted the “woke” Baptists long before Sam Francis did.

Hargis did waste time on criticizing several ecumenical efforts like the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, however, and he was only somewhat on the mark when he criticized the National Council of Churches (NCC) for its Leftism and supposed sympathy for communism. The NCC was most certainly Leftist, but they steered clear of open support for communism. It is certain that the NCC was highly sensitive toward Hargis’ activism. At the end of the Cold War, it was revealed that the Soviet KGB had in fact infiltrated the World Council of Churches, so Hargis was indeed correct in pointing out that some economical bodies had served communist aims during the Cold War.

On the other hand, Hargis did help to craft a Right-wing ecumenical fellowship, especially between Evangelical Protestants and Mormons.

Hargis was an unapologetic supporter of the American government. He wrote:

I believe in the Constitution of the United States, and in the Constitutions of the fifty Republics that make up these United States. I believe that communism violates all of our freedoms that we have enjoyed as Americans. I believe that communism is opposed to our American ideals, transgresses our traditions, is weakening our nation’s unity, and is wrecking our American way of life.[4]

Hargis’ support for the middle-of-the-road America of 1960 and his focus on communism was ultimately narrowing, however. The quote above shows the limitations of his activism. The constitutions of America’s 50 republics are easily amended, and the US Constitution can be reinterpreted by activist judges in any way they please. There is therefore plenty of ruin possible in “republics” and “constitutions.”

In the 1960s, while Right-wing activists like Hargis were on the lookout for a Soviet attack, they missed the fact that the American state could more easily be captured by sub-Saharans and other minorities, as well as foreign pressure groups like the Israel lobby. Indeed, one of the fifty states, Hawaii, is so alien from the rest of the nation that its entry into the Union should be considered a mistake.

Hargis’ criticism of the “civil rights” movement was mostly aimed at its idealist white supporters, not those Africans who benefited from it. He also misunderstood just how revolutionary and disastrous the 1964 Civil Rights Act would turn out to be. To put it a different way, Hargis focused on the faraway threat from communism and the Soviet Union but missed the bigger threat that was “civil rights,” Africanization, the Great Replacement, and the JQ.

Hargis’ career led to a number of court cases related to freedom of speech that were interesting from a legal perspective, but they mostly fall beyond the scope of this article. In the final analysis, Hargis had big successes in some areas but missed the mark in others. Regardless, his career is worth some study.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Bibliography

Penabaz, Fernando, Crusading Preacher from the West: The Story of Billy James Hargis (Tulsa: Christian Crusade Publishing, 1965).

Notes

[1] Billy James Hargis, The Real Extremists: The Far Left (Tulsa: Christian Crusade Publishing, 1964) p. 144.

[2] Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (London: Eyre Methuen Ltd., 1972), p. 492.

[3] Billy James Hargis & Bill Sampson, The National News Media: America’s Fifth Column (Tulsa: Crusader Books — Christian Crusade, 1980).

[4] Hargis, The Real Extremists, p. 5.

The%20Cold%20War%20Preacher%3A%20A%20Look%20at%20the%20Career%20of%20Billy%20James%20Hargis

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 582: When Did You First Notice the Problems of Multiculturalism?

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

Right-Wing Values in the Halo Series

-

Looking for Anne & Finding Meyer, Part 3