50 Classic Tales: The Western Folk and Fairy Tale Tradition is a collection of classic European folk stories published by The White People’s Press which offers not only the stories themselves, but the vital ethno-cultural context from which they sprang.

In this volume’s invaluable Introduction, translator Paul Marlais outlines a brief history of the folk tale within the proto-European and Indo-European traditions, which stretch back into the misty remembrances of pre-history. He underscores the value of these stories as entertainment, morality fables, and cultural artifacts. He also provides etymological links with the past by connecting modern English terms such as “folk,” “fairy,” and “lore” to their Germanic, Ancient Greek, and Indo-European roots. By referring to how folk tales tap into the “collective soul” and “spiritual consciousness” of Europeans, Marlais provides ethnocentric reasons for why these primeval narratives retain their vitality today:

The origins can be difficult to determine, but if folktales are indeed manifestations of shared cultural traditions rooted deep inside of us, this could explain why we have remained captivated by them through the ages, and even today participate in a collective unconscious experience when we engage with them. That may seem like a pleasant thought to a people prohibited from consciously embracing their collective identity, consciously exercising their collective interests, and consciously accepting their culture to be a product of their collective reality, but if the “collective unconscious” exists, it should symbolize a problem to be overcome by increasing collective consciousness.

After chronicling the history of these stories, from Aesop to Giambattista Basile in Renaissance Italy through the Brothers Grimm in Germany and Andrew Lang in Britain to Hans Christian Andersen in Denmark, Marlais takes an unexpected turn: He explores the non-European — and frankly, Semitic — origins of many of these tales. In their original forms, many of them contained repugnant themes such as incest, rape, pedophilia, and prostitution. They, along with the pantheon of Greek and Roman gods and much of what runs through Homer and Hesiod, had their start among the Phoenicians and other Semitic tribes from the Ancient Middle East. The Oedipus story, for example, predates Sophocles by centuries and is considered “a standard folktale” from pre-Mycenaean times:

Herodotus wrote 2500 years ago that the Greek gods were not Greek, but twentieth century scholarship ended all debate by showing that the entire Greek pantheon is more or less overlaid with Near East deities or of outright West Semitic origin. “Kadmos,” the founding figure of Greece and the Theban aristocracy that ruled during the Mycenaean era, comes from the West Semitic root q-d-m ( קדם ), meaning “man of the east.” Formative “Western” texts like the Iliad and the Odyssey are similarly so entwined with Near East symbolism that they are unlikely to have originated from a Greek source. And Ancient Greek culture, whether perpetuated by actual Greeks or not, would remain deeply nostalgic toward this period of mystery and material prosperity, dramatizing through art and literature the lives Kadmos’ heirs, and distant historical events like the Trojan War.

And what of the stories themselves? Well, let’s just say that Snow White in her original form was about as pure as the driven slush:

Ovid’s “Chione” (Χιόνη being Ancient Greek for “snow girl”) is about a girl whose beauty is the subject of immense scorn and desire from humans and the gods. At fourteen, Chione is escorted to the heavens by Hermes, where she is put to sleep so that he and Apollo can rape her. She then gives birth to (half-) divine twins, but her beauty, as well as her vanity, angers the Roman goddess Diana (Inanna-Iŝtar), who kills her. A lexical connection and basic plot elements of Snow Whites are present, but themes can traced back further through the West Semitic mythological text Inanna and the Netherworld.

Marlais provides the following fascinating side note: In the West Semitic, or Akkadian, version of “Snow White,” the goddess descends to the underworld to find Chione, and only “by courtesy of the Annunaki, seven inhuman, sexless creatures, who act as judges of the dead, is she allowed back to life.”

Does this ring a bell with anyone? It should. Here we are reading the origin of the seven dwarves! Each septet presides in some fashion over their beautiful heroine. And while the Annunaki live in the underworld, the seven dwarves not coincidentally work in a mine.

These kinds of nips and tucks we can credit to the Grimm Brothers and Frenchman Charles Perrault who, more than just collecting and cataloguing these ancient stories, purged them of their illicit content. Essentially, these men made them fit for Christian children: moral, decent, chaste, and virtuous. But here and there, some tidbits of their scandalous originals remain. I have always wondered why these curious details appear without any organic reason: the seven dwarves (why seven? why dwarves?), Cinderella’s glass slipper (how can you identify a girl from her shoe?), and the bartered infant in Rumpelstiltskin and Rapunzel (what do the imp or the witch have to gain from taking on a baby?).

Well, now we know. These are worldly story elements which have been sanitized for young readers — and done so masterfully, as generations of Western children can attest. Sadly, however, in the past century and a half, Jewish folklorists have besmirched the names of Andersen, the Grimms, and others for not preserving these morally ambiguous and sexually explicit storylines. Names such as Joseph Jacobs, Bruno Bettelheim, Jack Zipes, and Maria Tatar receive pointed scorn from Marlais for their degenerate influence on these classic tales. For example, in completely omitting the backstory about the Giant having murdered Jack’s family and stolen his birthright, Jacobs’ retelling of “Jack and the Beanstalk” paints Jack as a greedy thief rather than a conquering hero. On any occasion modern authors revise classic stories from the villain’s perspective, you’re seeing the results of people like Jacobs.

When Tatar complains about how the Grimms stripped “Oedipal conflicts” and “depictions of incestuous desire” from these stories, Marlais writes cuttingly: “What Tatar does not understand is that ‘Oedipal conflicts’ are features of her culture, not the culture she is pretending to represent.”

As with everything, there is a struggle over these ancient stories, and at stake is the identity and character of the West, and of white people specifically:

What is most admirable about the Grimms is their conscious, life-long devotion to strengthening the collective identity of their people, and those people hated the first edition of the Märchen because it was alien and grotesque. But the Grimms went right back to work, deconstructing it, removing the foreign elements, and finding ingredients that were natural, recognizable, and agreeable. Their eventual success resulted in the entire Western world becoming conscious of their collective identities and discovering newfound value in their heritage. And the main criticism of the Grimms is actually their greatest achievement: understanding that the tale is not always something that can be extracted purely and admired innocently, but something that is always being written and rewritten — if not by one’s own folk, by that of another.

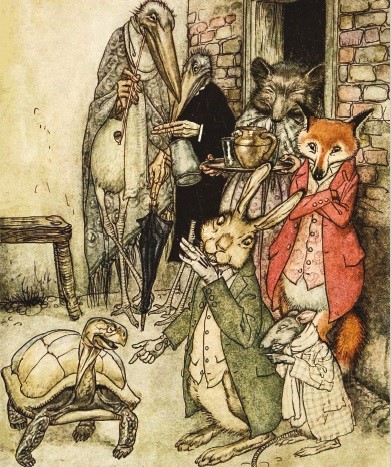

After a tour de force introduction like Marlais’, one would think that the remainder of 50 Classic Tales would be somewhat of a letdown. Nothing can be further from the truth. The tales are as delightful — and in some cases haunting — as one would remember. Editor Tony Vermont divides the stories sensibly by compiler or by geographic region. He starts with Aesop and offers such classics as “The North Wind and the Sun,” “The Hare and the Tortoise,” “The Fox and the Grapes,” and “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” all accompanied by their versions in Latin. Want to know why bats only fly at night? “The Birds, the Beasts, and the Bat” tells us, a fable which was new to me.

To his great credit, Vermont includes a fable which I am sure has been edited out of most twentieth-century compilations. “Washing the Blackmoor White” is so brief it is worth quoting in full:

A man who purchased a black servant was persuaded that the color of his skin was a result of dirt that had collected due to neglect by his former masters. After bringing him home, the Man attempted to clean the servant in every possible way, subjecting him to endless scrubbings. The servant became sick, but his color never changed, as what’s bred in the bone sticks to the flesh.

What could be more relevant to today’s racial struggles in the West than this?

Next, Vermont gives us the tales from Italy during the Renaissance, when these popular oral stories were first being written down. Basile and Giovanni Francesco Straparola led the way and had a tremendous influence on the Brothers Grimm centuries later. Included in 50 Classic Tales are “Constantino’s Cat” (the original version of “Puss in Boots”), “The Three Brothers,” “The Merchant’s Monkey,” and “The Egg of Columbus.” “Cesare’s Judgments,” a sad, cautionary tale about the promotion of incompetence, is particularly powerful.

One can’t help but note the fable-like quality of many of these stories and how the protagonists tend to be male (unlike those of the Grimms and Hans Christian Andersen). Vermont also includes a brief tale called “Buttadeu,” which he describes as “one of the oldest versions of one of the oldest tales in Europe, with variations in nearly every region of Europe and beyond: ‘The Wandering Jew.’”

You can buy Spencer Quinn’s novel White Like You here.

As everyone knows, the heavyweights of the fairy tale genre are the Brothers Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. Vermont includes their A-list : “Sleeping Beauty,” “Rumpelstiltskin,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Snow White,” “Cinderella,” “Rapunzel,” “The Frog Prince,” and “Hansel and Gretel.” What collection of fairy tales would be complete without them? 50 Classic Tales also includes details which may have been edited out in later, more trimmed-down editions. For example, in “Snow White,” the evil Queen at one point tries to strangle our heroine with lace. And the end met by Cinderella’s step-sisters in 50 Classic Tales is far more gruesome than I remember in any version I have read — either as child or to my own.

Fortunately, Vermont also includes the following less well-known Grimm yarns, ones that have been more or less purged from the fairy tale canon (for obvious reasons): “The Good Bargain,” “The Jew Among Thorns,” and “Der Judenstein.” The first two involve gentiles turning the tables on opportunistic Jews, who end up getting their just desserts. “Der Judenstein” (or “The Jew Stone”), on the other hand, is a haunting depiction of the ritual murder myth, which Jews have condemned as gross anti-Semitic superstition for centuries. Fair enough. In this tale, however, we experience the horror and loss white gentiles must have felt whenever outgroup members kidnapped and murdered their children — which did happen. And in this story, the Jews get away with it. Chilling stuff.

We also cannot forget how the Grimms describe the witch in “Hansel and Gretel”: “but she had a big and powerful nose like beasts and bad people . . .”

After reading these stories from across Europe, one is struck by the recurring themes:

- The king with a daughter who does not laugh (“The Golden Goose,” “The Good Bargain”)

- The benefactor disguised as someone or something lowly (“Mother Holle,” “The Frog Prince,” “The Golden Goose”)

- Tests, the passing of which brings reward (“Cinderella,” “The Golden Goose,” “Rumpelstiltskin,” “The Tinderbox”)

- Succession of power (“Cinderella,” “Rapunzel,” “Rumpelstiltskin,” “Sleeping Beauty”)

- Uncontrollable dancing (“The Jew in Thorns,” “The Red Shoes”)

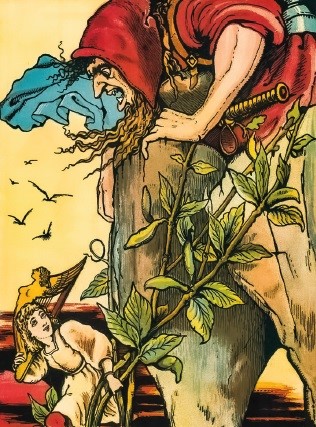

- The evil giant who smells intruders (“Jack and the Beanstalk,” “The Giant Who Had no Heart in His Body”)

- The villain with the magic object (“Snow White,” “Jack and the Beanstalk,” “The Tinderbox”)

- The wicked stepmother (“Cinderella,” “Snow White,” “Mother Holle,” “Hansel and Gretel,” “The Laidly Worm”)

This last theme deserves note because it hints at the Semitic origins of many of these stories, which Marlais discusses in the Introduction. Imagine a people high in individualism and relatively low in ethnocentrism having to contend with highly collective and clannish minorities living among them. Such minorities — when cast in the worst possible light as villains — would value blood relations and denigrate outgroup members to the fanatical lengths found in many of these stories.

Another major theme is the preying upon of children — either as innocent victims or as objects of barter. Villains seem to prize children most of all in fairy tales, and they are willing to part with a great many things in order to acquire one. The list here is fairly long: “Rapunzel,” “Rumpelstiltskin,” “Der Judenstein,” “Hansel and Gretel,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” “The Girl and Her Godmother,” and “The Three Princesses of Whiteland.”

Yes, such themes would fascinate small children, most of whom would be horrified at the prospect of being separated from their parents at such a precious age. On the other hand, could there be any truth behind this? Could there have been a battle for propriety going on back when these tales were being refashioned for young minds? Could parents have wanted to scare children away from the funny-looking people who (they say) might snatch them at any moment? It is possible that these tales evolved into eugenic defense mechanisms against those whom the Jolly Heretic Edward Dutton would refer to as “spiteful mutants” — that is, people born with maladaptive traits who seek to destabilize society? Seeing how such maladaptive people in the transgender and LGBTQ movements are fighting over our children today, the wisdom behind many of these fairy tales becomes clear.

As if this weren’t already enough, the jewel in the crown of this wonderful anthology is the section on Hans Christian Andersen. These eleven stories grow increasingly dark and powerful as the page numbers increase. I never understood what a genius storyteller Andersen was until I read this book. “The Steadfast Tin Soldier” is a stirring tale of devotion. “The Ugly Duckling” is the archetypical coming of age story. The psychology behind “The Emperor’s New Clothes” is as deft and insightful as anything in fiction. “The Tinderbox” turns the villain-with-the-magic-object theme on its head with the following brutal passage:

“What are you going to do with the tinderbox?” the soldier asked.

“That is not your concern,” replied the witch. “You have the money, now give me the tinderbox.”

“I’ll tell you what,” said the soldier, “if you don’t tell me what you are going to do with it, I will draw my sword and cut off your head.”

“No!” cried the witch.

But the soldier immediately drew his sword and cut off her head.

And the story only gets better from there.

While younger children should probably stay away from the final three stories in this section, children in middle school or higher should be required to read them. Why? Because they are both darker and, dare I say it, better than Edgar Allan Poe. Where Poe makes the supernatural the primary element of his work — the sole purpose of which is to frighten or unsettle the reader –, Hans Christian Andersen’s relation to the supernatural in these stories is, well, extremely Christian. This lends a strong spiritual flavor to his narratives which tap into dilemmas and struggles as old as mankind itself. Thus, “The Little Match Girl,” “The Story of a Mother,” and “The Shadow,” while certainly horrifying, would not qualify as horror. They surpass horror.

“The Little Match Girl” is punch-in-the-gut tragic, and rivals Dickens and Gissing in its portrayal of nineteenth-century poverty and destitution. “The Story of a Mother” depicts a young mother on a bizarre and profound search for her lost infant after Death had taken him away. I’m wracking my mind for apt comparisons: Twain’s Mysterious Stranger? Goethe’s Faust? The Book of Job? There is a reason why this incredible story has been adapted into film nine times. And as for “The Shadow,” all I can say is that it was The Twilight Zone before there was a Twilight Zone. It has the macabre twist ending to end all macabre twist endings. It’s hard to believe such a story fits within a book of fairy tales, but it does.

Finally, no review of 50 Classic Tales would be complete without mentioning the wondrous artwork which appears on nearly every page. Vermont manages to include the original, centuries-old art which accompanied these stories in their earliest written forms. He also provides brief biographies of the artists. What a splendid idea! In reading 50 Classic Tales and gazing at these incredible illustrations, one is transported back in time, not only in one’s mind but in one’s mind’s eye as well.

Here are five of my favorites — and the art is so good, it was difficult limiting myself to only five. These only scratch the surface of what can be found in this marvelous collection.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

50%20Classic%20Tales%20from%20The%20White%20Peopleand%238217%3Bs%20Press

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 582: When Did You First Notice the Problems of Multiculturalism?

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

Right-Wing Values in the Halo Series

-

Looking for Anne & Finding Meyer, Part 3

7 comments

Wow, great review! I’m very excited to acquire this book, as the topic is right up my alley, or one of my alleys, anyway. You know, I read that in the Jew in the Thorns, a scholar researched the origins of the story, and in every local folk version of the story it’s a friar and not a Jew! The Grimm brothers were anti semites who supposedly added deprecating bits about Jews whenever they could, where none existed in the original stories!

The quarterly journal for White People’s Press looks pretty good too. I wish you guys had made me aware of it more soonly.

That many of these essentially European stories have roots in similar stories from the Near East should put to bed this Christian vs. Pagan thing that flares up every now and again on this side of things.

Charity towards one another, folks. We’ve got bigger fish to fry.

Yes, the Lady Europa herself, Zeus’ bride, was a princess of Phoencia, a Levantine place which is also the matrix of our alphabets. Our Indic numerical system came to us through the Semitic Saracens.

But what many folks forget is that while origin is significant, what is truly compelling and determinative is what our people have done with anything we have imported. We make them unmistakably ours. Be it with religion, language or numbers, our restless race’s creativity is unmatched.

Thank you for this essay.

Dunno. I tend to be skeptical of Freudian readings of fairy tales. Little Red Riding Hood is really about STDs. Or maybe that was Rapunzel.

🙂

‘[These tales], along with the pantheon of Greek and Roman gods, and much of what runs through Homer and Hesiod, had their start among the Phoenicians and other Semitic tribes from the Ancient Middle East.’

Steady on, old chap! The chief of the gods, at least, has a secure Indo-European etymology. When we compare Greek ‘Zeus pater’, Vedic Sanskrit ‘Dyaus pita’, and Latin ‘Iuppiter’ we can feel confident that the Proto-Indo-Europeans worshipped a sky-god with a name something like ‘Dyeus pater’, meaning ‘Father Dyeus’, with ‘Dyeus’ probably linked to a word for ‘day’ (cf. Sanskrit ‘diva’ meaning ‘during the day’, Latin ‘dies’ meaning ‘day’). So perhaps ‘Father Day’ or ‘Father Sky’ or similar.

It’s true that Dyeus is the only god that we can securely reconstruct by name for Proto-Indo-European. (There are also good grounds, however, for reconstructing a pair of divine twins, sons of Dyeus, who show up in Greek as Castor and Pollux and in Vedic as the Ashvins.) But what of it? Names of gods change down the centuries as they become known by what were previously epithets.

My impression is that the alleged derivations of the Greek gods from Semitic deities are not as solid as Quinn and Marlais are making out here. In fact the only candidate for which a really extensive case has been made, as far as I know, is Aphrodite, who is often linked with the Phoenician goddess Ashtart. But even there there is no link by name. Some scholars have tried to convince us that ‘Aphrodite’ was what resulted when some early Greeks tried to pronounce ‘Ashtart’, but this is massively unconvincing. The Phoenician goddess’s name was later directly borrowed into Greek as ‘Astarte’, after all, which is obviously much closer than ‘Aphrodite’. The truth is that we just do not know the origins of a lot of the Greek deities. But an Indo-European origin is as likely as a Semitic one in the vast majority of cases.

Marlais claims that the Iliad and the Odyssey are ‘so entwined with Near East symbolism that they are unlikely to have originated from a Greek source’. An argument for this very strong claim would have been nice. I can think of no grounds for it whatsoever. Remarkably, an Indo-European origin can be supported (if not proven conclusively) even for some individual phrases in Homer, as with the formula ‘kleos aphthiton’ meaning ‘imperishable fame’ (what every good Indo-European warrior is striving for), which is precisely cognate with the Vedic Sanskrit ‘akshiti shravas’, with the same meaning.

And note the slippery wording here: it is claimed that we are dealing with ‘Near East symbolism’. It is easy, in context, to take evidence for ‘Near East symbolism’ (not that we are given any such evidence!) as evidence for a Semitic origin. But this does not follow. The cultures immediately to the east of Greece, in the ancient world, included those of the Hittites, Luwians, and Persians, who were all speakers of Indo-European languages. Marlais brings in a reference to Greek attraction to tales of Troy, as if that proved something or other. He does not know, perhaps, that the Indo-Europeanist Calvert Watkins has argued on the basis of epigraphic evidence that the Trojans spoke Luwian, an Indo-European language closely related to Hittite.

I recommend Watkins’s book ‘How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics’ as a good introduction to this general area. For an actual scholarly treatment of Near Eastern cultural influences on Greece, I recommend Martin West, ‘The East Face of Helicon’, later counterbalanced by ‘Indo-European Poetry and Myth’ by the same author.

Any actual Classicists, Sanskritists, or Indo-Europeanists reading this, please forgive the imprecise transcriptions!

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment