“The Day After, ABC‘s much-discussed vision of nuclear Armageddon, is no longer only a television film, of course; it has become an event, a rally and a controversy, much of it orchestrated.”

— The New York Times, November 20, 1983

I have a somewhat morbid fascination with nuclear war. It is one of the absolute worst and unimaginably nightmarish things that could theoretically happen. When you step back and think about the bullet that the human race dodged during the Cold War, it is truly mind-blowing. If anything, it’s really the bullet that fascinates me, and my fascination really isn’t that morbid, because the more I think about it, the more grateful I am for what I have. Watch a few Protect and Survive videos and you’ll start feeling a lot better about your problems.

Most people have no idea that the world almost ended on September 26, 1983. On that day, Soviet missile detection systems glitched out, and it appeared that the United States had launched five ICBMs at Russia. Mandatory Soviet protocol for such an event was to launch a full-scale nuclear attack in response, but Stanislav Petrov, the commanding officer on duty, refused to do so. He guessed correctly that it had to be a mistake, because a real American first strike would have involved hundreds of missiles. But had someone other than Stanislav Petrov been on duty that day, who knows? I might be writing this article on a stone tablet right now.

These days, a nuclear war seems only slightly more probable than a zombie apocalypse, but I’m old enough to remember the Cold War, when nuclear war was a real possibility and constantly hung over mankind like the Sword of Damocles. A lot of people believed that nuclear war was inevitable. Why wouldn’t it be? Given that the history of mankind since ancient times had been a story of constant warfare, it seemed likelier that a nuclear war would happen sooner or later than that the human leopard would suddenly change his spots.

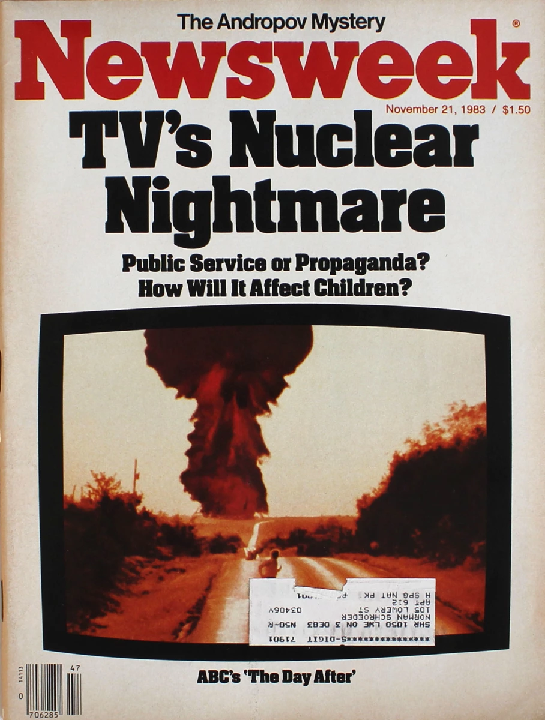

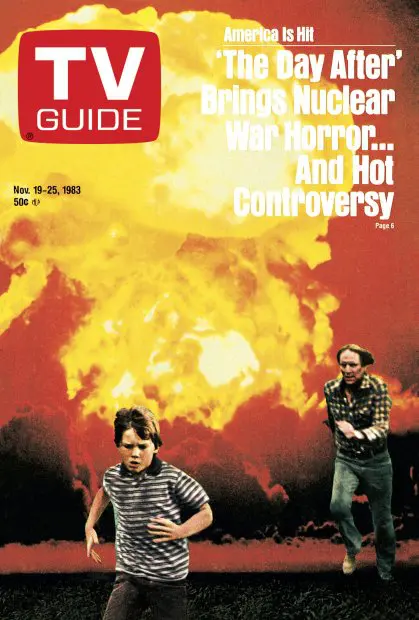

I previously wrote an article where I talked about how 1980s America was completely obsessed with nuclear war, and a number of people with bad memories from that time commented to tell me I was wrong and that fears of nuclear war had subsided by the 1980s. They are wrong. There is probably no bigger piece of evidence for that than the culture phenomenon that was The Day After.

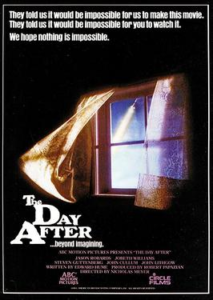

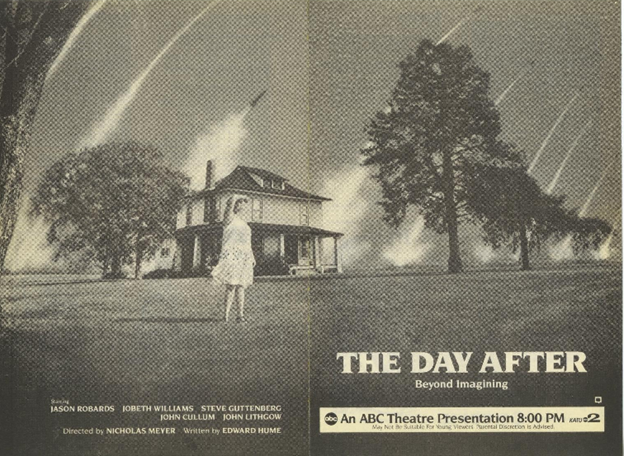

The Day After was a made-for-TV movie that attempted to depict what a nuclear war would look like and what life would be like for those who were unlucky enough to survive. It’s shown from the perspective of regular people in Lawrence, Kansas. There are no politicians or generals in The Day After. It’s about average Americans who are merely going about their lives when all of a sudden, a nuclear war breaks out. For months before it aired, The Day After generated extraordinary hype and controversy as it promised to be the most brutal, realistic, and uncompromising depiction of nuclear war ever filmed. It’s on YouTube, and you can watch it here.

The Day After aired on ABC on November 20, 1983, the Sunday before Thanksgiving. It was watched by 100 million people — half of all American adults — and remains the most-watched made-for-TV movie of all time. It is still the fifth-most watched non-Super Bowl American TV broadcast in history after the series finale of M*A*S*H*, the episode of Dallas where they revealed who shot J.R., the series finale of Cheers, and the 1994 Olympic Ladies’ figure skating contest (which drew interest due to the Tonya Harding/Nancy Kerrigan controversy).

By all accounts, no one initially involved with the project anticipated that it would become as big as it did. Director Nick Meyer has stated that he did not believe that The Day After would ever be shown on television, as he believed someone would surely pull the plug on it before it was broadcast. That was what happened to the BBC’s 1966 nuclear war docudrama The War Game. The BBC produced the 45-minute film, but before it could air, the British government determined that it would be far too upsetting to be shown on television. It was given a limited theater run and shown at several film festivals, and later won an Academy Award for best documentary. It was eventually shown on British television nearly 20 years later, in 1985.

But The Day After did air, and as the broadcast date neared, it had become a cause célèbre. There were several controversies surrounding it.

First, conservative Cold War hawks were concerned that there was a political agenda behind it. At the time, Reagan was in the process of a nuclear build-up, and even before The Day After had aired, it was being championed by the anti-nukes movement, which believed that the West should disarm itself, unilaterally if necessary.

Second, the movie never specifies which side launched its nukes first. Conservatives were outraged at the suggestion that, if Armageddon ever came, that it might be America’s fault, and said that this implied a moral equivalence between the US and the “evil empire.” While they may have struggled to put their finger on how or why, conservatives felt in their guts that this had to be commie propaganda.

Lastly, there was concern that The Day After would be emotionally and psychologically damaging to children. Nuclear war is something that scared the living shit out of grownups, so surely the kiddies wouldn’t stand a chance.

In a November 7 New York Times article entitled “The Impact on Children of The Day After,” a psychologist named Dorothy Singer is quoted:

The sense of loss suffered by the families on the screen may provoke profound fears about children’s separation from parents. I fear children will have nightmares about the show and worry about it for weeks or even months. Older children and adults may have a sense of hopelessness.

The same article quotes Tom Roderick of Educators for Social Responsibility:

The threat of nuclear war is real, millions of children are aware of the danger and parents can’t reassure children that this is a fictional situation.

Educators for Social Responsibility put out a pamphlet for parents on how to talk to their kids about the movie. “Rather than informing young viewers and inspiring them to seek solutions, the film may leave them numb and resigned to the inevitability of nuclear catastrophe,” it informed them.

The week before The Day After aired, the children’s show Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood, a program where host Fred Rogers would talk to children in his famously calm and reassuring voice about their fears and concerns, ran five half-hour episodes on nuclear war.

Americans had been talking about nuclear war for decades and had imagined what it might be like, but now for the first time they were going to actually be shown it. Expectations were that minds were going to be blown on a massive scale. ABC distributed 500,000 viewing guide pamphlets to libraries, churches, and community centers with the aim of mentally and emotionally preparing people for the film. Some ABC affiliates set up toll-free counsellor hotlines for anyone who was disturbed after watching it.

There was some wrangling between the network and the director over how long The Day After should be. The network initially wanted the film to be four hours and broadcast over two nights for maximum advertising revenue. Director Nick Meyer wanted a three-hour film, and was adamant that it be shown in its entirety on one night for maximum effect.

In the end, The Day After was two-and-a-quarter hours long and shown on one night. This was mostly due to the fact that many advertisers wanted nothing to do with the film and had no interest in associating their brand with the worst thing imaginable. As Meyer recalled:

General Mills, General Motors, General Foods — all the Generals had headed for the hills. So suddenly the advertising revenues that were anticipated became completely moot. That’s how it became a two-hour movie as it always should have been.

There were some commercial breaks early in the film, during the peacetime segments, but after the first missiles are fired, the movie broadcast the remainder commercial-free. A three-hour workprint version has also surfaced on the internet.

Nick Meyer decided that the film would be more effective and believable with unknown actors. It would have distracted people from the subject matter and break immersion to have recognizable actors on the screen, causing the viewer to constantly think, “Hey, I know that guy! Oh, and there’s the cop from that one show! Look! It’s Janet from Three’s Company!” The only established star in The Day After was Jason Robards, who had previously won two Academy Awards for Best Supporting Actor. However, the movie does feature then-unknown actors John Lithgow and Steve Guttenberg, who would later become stars in their own right.

Nicholas Meyer explained:

As a movie, I was well aware even at the time of its shortcomings. There is a paradox about nuclear war in that it is the most urgent problem that has ever confronted the human race . . . but at the same time it’s such a terrible dilemma that none of us can really bear to think about it. So if you make a movie about it, the audience will go anywhere their minds can rationalize to avoid confronting the movie. They’d rather talk about the music or talk about how Jason Robards was brilliant — anything, other than the subject. So as a director I found myself engaged in a counterintuitive exercise of trying not to make a good movie. . . . I didn’t want people talking about Jason Robards. I didn’t want people talking about the music — which is why after the opening credits there is no music. I viewed myself as not wanting to make a movie but a public service announcement: If you have a nuclear war, this is what it’s going to be like — only probably not this good.

Meyer wanted The Day After to have an authentically Midwestern feel. It was filmed on location in Lawrence, home of the University of Kansas and close to where a lot of America’s Minuteman missile silos were stationed at the time. Fifteen of the speaking cast came from Los Angeles, while the rest were local theater actors from the Kansas City area. The extras were all local volunteers.

The Day After can be broken into two halves: before and after the attack. The film centers on two families. The first is the Oakes family, of whom cardiologist Russell Oakes (Jason Robards) is the patriarch. As the film opens, Russell learns that his daughter intends on moving to Boston because she wants to be closer to some guy she likes. This makes him sad, but she’s a grown woman now, so what can he do? The Oakes live in Kansas City, which takes a direct hit in the war, killing all of the Oakes family except for Russell, who is on the highway driving back from Lawrence, where he teaches a class, when the missiles strike.

The other family is the Dahlbergs, a farming family who live in Harrisonville, 40 miles away from Kansas City. As the film opens, the big news in the Dahlberg family is that their daughter, Denise, is to be married soon. Alas, the wedding becomes indefinitely postponed after her fiancée is vaporized in the war.

The first half of The Day After follows these characters as they go through their ordinary — and sometimes humdrum — lives. All the while, there are radio and TV news reports playing in the background which become progressively more alarming. The Soviets have blocked off West Berlin, leading to a huge crisis. Then the Soviets invade West Germany. Then NATO responds with tactical nuclear weapons. The extra footage in the workprint version mostly comes from this pre-attack part of the film and includes more of these news reports, filling in the backstory leading up to the war.

We meet some other characters in the first half. There is a black soldier who tries to reassure his wife that the crisis is nothing to worry about before going off to his assignment, guarding a missile silo. There is John Lithgow’s character, who is the science director at the University of Kansas. There is Steve Guttenberg as University of Kansas pre-med student Stephen Klein. We also have Dr. Sam Hachiya, a wise-cracking Asian doctor who works at the campus hospital.

Interestingly, the workprint version of The Day After includes a scene which suggests that Dr. Hachiya is an anti-Semite. There is a scene where he is giving Steve Guttenberg a physical examination Sam asks Stephen for his name. After he gives it, Sam lowers his glasses, looks at Klein, and sarcastically says “Japanese?” — a sort of sly way of saying, “Oh, so you are a Jew.”

Shortly afterwards, Sam asks, “What’s your major, Stephen?” “Pre-med,” Stephen replies. In the broadcast version, the scene ends here, but in the workprint version, Sam replies, “Are you kidding me? What, you think doctors make a lot of money or something, huh?”

The situation in Europe escalates quickly, and people become increasingly nervous, but there are still people who doubt there is any danger. There is a scene where some college students are listening to a radio news broadcast and hanging on every word when a bespectacled girl scoffs at the reports.

Student #2: Fantasyland!

Aldo: You think they’re making it all up, like War of the Worlds or something?

Student #2: Look. Did we save the Czechs or the Hungarians or the Afghans or the Poles? Well, we’re not going to nuke the Russians to save the Germans. I mean, if you were talking oil in Saudi Arabia, then I’d be real worried.

Panic starts to take over as the news coming out of Europe gets ever grimmer. People start evacuating the city. There is a scene in a supermarket where the place is a madhouse. The shelves are rapidly emptying as people buy carts full of food. We learn that the conflict has spread to the Persian Gulf, where the Soviets and Americans have started sinking each other’s ships.

The question of whether there will be a war or not is finally settled when everyone sees the Minuteman missiles being launched, with everyone knowing that a Soviet return strike is now inevitable. At the Dahlberg house, mother Eve Dahlberg refuses to confront reality and continues making preparations for Denise’s wedding. As the Soviet missiles are minutes away from impact, Eve is still busily making the beds as if nothing is wrong. Father Jim Dahlberg finally has to drag a hysterical Eve down to their basement.

A Soviet bomb detonates in space over the US, generating an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) which fries everything electronic across the country. Shortly after, the Soviet missiles strike their targets, and the death and destruction is incalculable. Nevertheless, the attack itself is just the beginning of everyone’s problems. After the attack, deadly radioactive fallout rains down across the state. The survivors have to stay in whatever shelter they have for several weeks afterwards until the radiation levels drop. This isn’t a problem for the Dahlbergs, who piled dirt around and stockpiled food and water in their basement. Nevertheless, their son, Danny, is blinded when he looks directly at a nuclear blast, as he is caught outside when the missiles hit.

Some of the characters like Dr. Oakes, Stephen Klein, and the black soldier were all on the highway when the attack came and have no choice but to walk through the fallout to safety. As a result, they all later develop radiation sickness.

Denise Dahlberg eventually snaps from the mental strain of spending so long in the basement bunker and runs out into the still dangerously-radioactive outdoors. There are dead farm animals strew all over the fields, and as Denise runs, white fallout dust kicks up with each step. Stephen Klein, who had taken up residence with the Dahlbergs, sacrifices himself to run out and talk Denise into coming back inside. Denise is heartbroken about the death of her fiancée, but over time starts to develop feelings for Stephen. Their romance is cut short when both of them come down with radiation sickness after their brief jaunt in the outdoors, however.

Dr. Oakes takes up residency at the University of Kansas campus hospital. The doctors struggle to treat the enormous crowds of ill and injured people who come to them with their limited resources. The EMP has deprived them of most of their sophisticated equipment. All they have for electricity is car batteries. Water is also a big problem, as doctors need a lot of it for cleaning.

ABC strenuously denied that there was any political message in The Day After, but there are some moments of sermonizing. At one point, a pregnant woman tells Dr. Oakes:

We knew the score. We knew all about bombs. We knew all about fallout. We knew this could happen for 40 years. Nobody was interested.

Several weeks after the nuclear exchange, the President makes a nationwide radio broadcast. When the film was first aired, the voice of the President was a Reagan soundalike, but in subsequent broadcasts it was changed to the voice of a generic stock character. He speaks over a montage of images of post-nuclear suffering and survivors with thousand-yard stares, which makes the speech sound like a sort of sick joke:

In this hour of sorrow, I wish to assure you that America has survived this tribulation. There has been no surrender, no retreat from the principles of liberty and democracy for which the free world looks to us for leadership. We remain undaunted before all but almighty God.

The struggle to rebuild begins, and it is not easy. The topsoil in the fields is now radioactive. The government advises the farmers to simply remove the first few inches of soil, but they balk at such a monumental undertaking.

Tent cities pop up all over the land. The government struggles to feed the survivors. We are shown a gymnasium full of people dying from radiation poisoning. Jim Dahlberg is killed by some squatters he tries to evict from his property.

Near the end of the film, Dr. Oakes, who has been working heroically and tirelessly at the campus hospital since the attack, starts to develop radiation sickness himself, and it is clear that he does not have much time left. He decides that before he dies, he would like to see his home in Kansas City one last time. Martial law is now in effect, and as Dr. Oakes makes his way to Kansas City, he witnesses many scenes of horror, including an Army firing squad executing looters.

When Dr. Oakes at least reaches his home, it is nothing but a pile of rubble which has been occupied by a group of squatters. For the first time in the movie, Dr. Oakes loses his cool. He yells at the squatters to get off his property. None of the squatters move, but one of them offers Dr. Oakes a fruit. Dr. Oakes falls to the ground and begins to weep inconsolably. The squatter comes over and put his arm around Dr. Oakes to console him.

The last voice you hear before the end credits is that of John Lithgow speaking into his CB radio, trying to contact the outside world. “Hello? Is anybody there? Anybody at all?”

After this, we see this message scroll by on the screen:

The catastrophic events you have just witnessed are, in all likelihood, less severe than the destruction that would actually occur in the event of a full nuclear strike against the United States. It is hoped that the images of this film will inspire the nations of this earth, their peoples, and leaders to find the means to avert that fateful day.

The initial broadcast was followed by a roundtable discussion hosted by Ted Koppel and featuring former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, General Brent Scowcroft, scientist Carl Sagan, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, William F. Buckley, Jr., and “Holocaust survivor” Elie Wiesel. You can watch it here.

The Day After was not the first movie of its kind, nor is it the best movie of its kind. A year later, the BBC released Threads which, despite having only a fraction of The Day After’s budget (£400,000 to The Day After’s $7,000,000), manages to be exponentially more intense. Watching The Day After will bum you out, but Threads will rape your mind and give you nightmares. You can watch Threads here.

Even director Nick Meyer has acknowledged that The War Game and Threads are more powerful movies than The Day After. He claims that he held back because there were concerns that people would just turn their sets off if it were too gruesome.

While The Day After is far from the best movie about nuclear war, it in terms of societal impact, it was the most explosive. The film started a national conversation about nuclear war and even rattled the most powerful man in the country. Ronald Reagan wrote about The Day After in his diary twice. After screening an advance copy of the film, he wrote the following in his diary on October 10, 1983:

Columbus Day. In the morning at Camp D. I ran the tape of the movie ABC is running on the air Nov. 20. It’s called The Day After. It has Lawrence, Kansas wiped out in a nuclear war with Russia. It is powerfully done — all $7 mil. worth. It’s very effective & left me greatly depressed. So far they haven’t sold any of the 25 spot ads scheduled & I can see why. Whether it will be of help to the “anti-nukes” or not, I can’t say. My own reaction was one of our having to do all we can to have a deterrent & to see there is never a nuclear war. Back to W. H.

Reagan mentioned the film again in his diary on November 18, 1983, two day before The Day After was broadcast. By this point, conservatives had strategized how they were going to spin the film: that a nuclear buildup is the best way to avoid nuclear war:

George [Shultz] is going on ABC right after its big nuclear bomb film Sunday night. We know it’s “anti-nuke” propaganda but we’re going to take it over & say it shows why we must keep on doing what we’re doing.

After Reagan signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 1987, his administration sent a letter to director Nicholas Meyer which read, “Don’t think your movie didn’t have any part of this, because it did.”

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Will There Be an Optics War II?

-

Pour Dieu et le Roi!

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

Civil War

-

The Holocaust Card Can No Longer Be Played

-

Problém pozérů aneb nešíří se snad myšlenky pravicového disentu až příliš rychle?

-

On Second World War Fetishism

-

The Mainstream Blues: Has the Dissident Right Already Won?

35 comments

“Who holds back the electric car? Who makes Steve Guttenberg a star? We do, we do!” — The Stonecutters Anthem

https://youtu.be/dSpOjj4YD8c

I recall watching this at the time, and can remember the scenes you describe, although I haven’t thought about it much since, except as a TV phenomenon. I haven’t watched the clip of the commentators, but I always remember Dr. K saying somewhere that “Scaring yourself shitless [or words to that effect] is not the best way to decide on policy.” I haven’t decided if that’s good old Republican common sense (in the law, they says “Hard cases make bad law”) or Dr. K at his most Strangelovian.

Speaking of Strangelove, the good Dr. would point out that you need a Doomsday Machine to make your deterrent believable, since you could fire off a few missiles and some American Petrov might decide it wasn’t a “real” attack.

The real deterrents were Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It showed the world that yes, those crazy Americans would not only use nukes, but they’d use them on civilian targets belonging to an already defeated enemy.

Sure thing. Bad Americans, good Russians who would not nuke children, they would only rape and bayonet them. Much more human.

It seems the USSR propaganda are well and alive. And as vile as always

I remember watching this in high school in the late nineties and laughing my ass off at the graphics as people were being vaporized. It did have a lasting impact on me because I own the DVD and pull it out occasionally. My favorite scary nuke movie though is Miracle Mile. Watch it, it’s awesome.

OK, I just watched Miracle Mile on your recommendation (again, I’m a huge nerd for all things nuclear war). It’s a good movie. It’s like a black comedy most of the way through and then gets really dark at the end.

In a way, it reminded me of the criminally underappreciated 80’s comedy Three O’Clock High which takes place over the course of a single school day and like Miracle Mile, also has a soundtrack by Tangerine Dream.

What I love about the movie is that while the city is rapidly spiraling out of control and into anarchy, you don’t know until almost the very end if this is really happening or if it’s some kind of sick joke.

My mom wouldn’t let me watch “The Day After” as a 12 year-old. A precocious kid, I became terrified of nuclear war after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan so my mother shielded me from “The Day After”. Watching as an adult years later I was moved by it’s humanity.

An army firing squad shooting looters…. How the world has changed.

These days it’s more likely to be January 6th sympathizers or maskless Americans. They might be handing environmentally sound bags to carry home the loot.

The threat of nuclear war loomed over my consciousness from birth all the way to the fall of the Berlin Wall. I even remember wondering if we would be able to build a fallout shelter under our tiny front lawn.

They made a ton of nuclear-war scare movies. https://creepycatalog.com/nuclear-war-movies/

Great list. Saw some of those; others never heard of.

Travis definitely picked a winner here. I remember watching this, and it created a lot of hoopla. As it was, it was an okay TV movie. They only had one major actor, Jason Robards Jr., so as not to make it a ‘star’ vehicle.

Also, I remember a final scene where the Mcnaughton farm, and the farmer is on his horse and finds some squatters on the land, tells them to leave, and one of them shoot him.

The scenes of the missiles shooting off around the rural areas was very powerful. since I lived in Columbia, Mo., and Whiteman Air Force base was in the region, we would have been a target, and the radiation would have swept all through the state. The weather and wind patterns meant the central part of America would have been exterminated.

I also remember the movie The War Game, released in 1983 with Matthew Broderick. Somewhat the same theme, but lighter.

The devastation in the film was pretty grim. I think the most powerful scene was the government agent urging people to scrape off that topsoil and plant…and he showed little confidence in telling people that. Really, there would be no meaningful government. This is what we want…but how to do it without nukes? Maybe now entropy is our best hope.

Like an Air Force manual on nuclear war said “Nuclear war will not mean the end of humanity…but it will mean the end of most people reading these words.”

I recall the panel they had, and Kissinger was very vocal about the film being anti-military. Also, Elie Wiesel was there in his role as professional survivor, and said no nation should have nuclear weapons…except Israel.

I also remember seeing The War game, and it is also pretty grim. It was teamed with another film by the same director, Cullodon, about the Scottish defeat in 1745 using the same timing techniques, and is pretty strong. “This is a cavalry saber. Here is what its thrust does.” And you see highlanders slashed to pieces by British dragoons. Also, showed the civilians wiped out, raped, and killed off by the vengeful British. Meanwhile, it mentions the Duke of Cumberland, who sanctioned the slaughter, was honored, praised, and Handel wrote a triumphant march in Cumberland’s honor, while Cumberland parties. Not nuclear war, but pretty nasty.

I think the grandfather of all these films was Pat Frank’s book Alas, Babylon, written in 1960, about people in Florida dealing with nuclear war. It showed a town relying on its own resources. Also, a little girl is blinded…I’m sure that was lifted for this film. What was interesting was how then, the first people to die off were diabetics, because of no insulin.

Also, the doctors had to arm themselves because of drug addicts searching for dope. In the book, the main character has a brother in the military who warned him nuclear war would start because of problems in the Middle East. A pretty effective book. Some have said it’s too dated in male/female relations and male dominance, but it’s obvious in a nuclear war, feminism and all the trans garbage would be extinct…as would most of their practitioners.

A Playhouse 90 version of Alas, Babylon was made in 1960 for TV. Dana Andrews was in it, as was Kim Hunter, Barbara Rush, and a young Burt Reynolds.

The BBC’s 1966 nuclear war docudrama The War Game . . .

When it was cancelled, a paperback was issued containing stills from the drama with script excerpts. It was actually more gritty, more scary, than the film itself.

Having a pronounced perverse streak, I was annoyed they’d banned the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons. Witnessing ‘Ivy Mike’ after ingesting a psychedelic would have been truly mind-blowing. But enough about me . . .

Project Orion was a plan to propel a ‘starship’ by detonating atomic bombs behind the craft. At the time, Freeman Dyson thought that radioactive contamination in the atmosphere resulting from a launch would mean a handful of premature deaths (he thought that would be too many), but – given the advances in technology since then – it must be possible to make relatively clean thermonuclear (fusion) devices. You could ship a shopping mall to Mars to await the first astronauts.

This was an excellent idea for an essay. Kudos to Travis for finding the relevant links. I recall the movie (not that well), and the controversy surrounding it (much better). As a hardcore Reaganite and Cold Warrior at the time, I definitely saw it as commie/liberal propaganda. The West had been being eclipsed in the arms race by the Soviets across the 1970s (I have a cool, heavily illustrated book on a shelf directly over my desk as I write titled Russian Military Power {pub. 1980, reprint 1982}, which provides all the gory details); there was a “missile gap”; and Reagan was elected in some part to do something about it (although almost everyone forgets that the 1980s defense buildup actually began under Carter in 1980 following the shock of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan). In typical leftist fashion, this movie was meant to undermine confidence in Reagan’s approach to the Cold War: naming Soviet tyranny and communist evil; rearming the West; deploying tactical nukes in Western Europe (which turned out to be an important turning point in the West’s ultimate victory); pursuing the Strategic Defense Initiative to develop anti-ballistic missile defenses; and fighting “proxy wars” against communist regimes and guerilla movements in the Third World.

Say what you will about Reagan, especially his silly “free trade” views which set the template for the deindustrialization of the American heartland, and his disastrous immigration sentimentalism, but his Cold War strategy worked, didn’t it? If the liberals had been in charge, the Cold War might still continue.

A lot of us were concerned about nuclear war growing up. Civilization is fragile to begin with, just look at the temporary effects of a natural disaster or civil unrest. It would be very difficult to rebuild after a nuclear war. Some of my favorite movies deal with the aftermath of it. This includes the original “Planet of the Apes”, “Logan’s Run” and the Mad Max” movies.

Check out A Boy And His Dog if you haven’t already.

I have seen it. It’s creative.

Anyone who says people weren’t concerned about nuclear war in the 1980s — especially the early-to-mid ’80s; by late in the decade it had subsided somewhat — either wasn’t there or was oblivious to his surroundings.

The third in the triumvirate of great ’80s nuclear war films is Testament, which came out the same year as The Day After but didn’t receive anywhere near the same hype, and has a very different approach to the subject. Also worth seeing are Where the Wind Blows, which is British and is quite powerful despite being an animated film, and Dead Man’s Letters, which was the Soviet contribution to the genre.

There was real fear of nuclear war in the early 1980s…I experienced it as a kid. It affected me. You felt powerless. My mother told me at the time that she suffered the same worries as a 12 year-old during the Cuban Missile Crisis. By the late 1980s, it all seemed to go away.

I confess, I was not at all concerned (and used to argue against people who were). I was very politically (and racially) aware (in 1981-82, I was President of my college’s GOP student chapter), and was more concerned about America being subject to nuclear blackmail by the Soviets, which explains my elation at Reagan’s 1980 victory. I was also vaguely concerned about getting drafted to fight the Soviets in a land war. But as an adult by 1980, I always thought MAD would be sufficient to deter ICBM rashness.

BTW, the threat of nuclear war breaking out somewhere is, due to proliferation, actually far higher today than during the Cold War.

You neglected to mention that the Petrov incident happened only a couple of weeks after the Soviets had shot down the Korean airliner that was carrying many Americans, including a US Congressman, and that this put US-Soviet tensions at their highest point since the 1960s. It likewise happened only a few weeks before Able Archer 83, a massive “training exercise” by NATO that was conducted in November 1983 (only two weeks before The Day After aired), allegedly to simulate the Western response to a Soviet invasion of Western Europe but which was in fact mainly intended to intimidate Moscow. It almost worked too well, as the Russians thought it was a cover for actual preparations for an attack and were nearly persuaded to launch a nuclear first strike before NATO could hit first. Some historians consider it the closest the two sides came to going to war after the Cuban Missile Crisis, although it didn’t have the same impact on society since no one knew it was happening at the time apart from people in the intelligence services. British television made a good documentary about this a few years ago.

I was going into 1st Grade when Korean Air Lines Flight 007 was shot down. I remember everyone talking about it but didn’t really understand the implications of it.

One thing I did remember is that there was this popular morning radio parody song about the incident going around called “The Russians are Liars” which was sung to the tune of “Eye of the Tiger”. I have looked all over the internet for this song to no avail. The best I’ve come up with is a few news articles talking about the song.

https://www.upi.com/Archives/1983/09/09/Radio-stations-nationwide-have-been-clamoring-for-copies-of/2881431928000/

Ah, that means you’re four years younger than me. I remember the Korean shootdown quite vividly, but I can see why a first-grader wouldn’t have grasped the implications.

Most people forget that the Right lost the great anti-communist/anti-NWO patriot Rep. Larry MacDonald (R) on that flight. What really happened to that flight? There has been much conspiracizing since:

https://rense.com/general91/lry.htm

The best explanation I’ve heard is that the jet’s navigation system wasn’t calibrated quite right, so it ended up going off course. Then it was assumed to be a spy plane, since a spy plane had been operating in the North Pacific not long before.

Congressman Larry McDonald (D-GA) was a rare example of a Conservative Democrat ─ one staunchly opposed to Communism ─ yet he did not strike me an as an Interventionist either.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Larry_McDonald

Prior to Watergate, many of the old school Democrat hawks were discredited by a recent proxy war in Indochina, which was not the brainchild of the GOP at all but from a group of “Defense intellectuals” dubbed the Whiz Kids, who tended to despise battle-hardened generals who had actually seen the elephant.

After a tragic assassination, President Kennedy’s successor was a wheeling and dealing Texas pol who then went all-in on his predecessor’s Proxy War scheme ─ but this did not turn out so well, even with the volume cranked up to traditional concert levels.

The flailing old guard in the Democratic Party was still obsessed with their Arthurian insurgent/proxy war in the election campaigns of 1968 and 1972 until all credibility was lost, and nothing was left besides the “Amnesty, Abortion, and Acid” faction.

My Aunt was the first female DNC Chair (1972). She was a New Deal Democrat and Mormon, and their family had made some modest money as mink ranchers in Utah before retiring in Scottsdale, Arizona where she was dabbling with her political organizing hobby.

After Johnson declined to run for reelection in 1968, no establishment Democrat dared run on a peace platform long after the Camelot cause had clearly been lost. This was still splitting the Democratic party in 1972, even though Nixon had done little to end the war, let alone actually win it somehow. He and Kissinger had even gone to Peking to smooch with Mao and company, something unthinkable for a Democrat since the FDR Brain Trust.

I think it is noteworthy of the change since the 1960s that no Democrat after JFK could ever be elected to the Presidency who was not also a good old boy from the South ─ not until Barack Hussein Obama in 2008.

Republicans had an easier time distancing themselves from Watergate than the Democrats from Vietnam. My aunt briefly describes in her memoirs how kooky Jewish Feminists took over the Democratic Party ─ and how a mild-mannered Southern Baptist from Plains, Georgia came out of nowhere with an old-fashioned folksy appeal. But Mr. Peanut’s uninspiring message of malaise and appeasement had short legs.

My side of the family were ultra-Conservative Republicans ─ parents voted for George Wallace and General LeMay in 1968, and Nixon in 1972. Unfortunately, as a kid I did not pay so much attention to the Christmas dinner political gossip of this era when so many dies were being cast. Today I would have many questions for those old people.

🙂

I think that’s correct. And I don’t remember any sense of outrage whatsoever about the atrocity. The establishment attitude was basically. Oh well, it happens.

🙂

The last thing I’ll mention is that it’s notable that Eve Dahlberg, the mother, was played by the stunning Austrian-American actress Bibi Besch, who was never a top-shelf actress but was nevertheless in many films during the 1970s and ’80s, including Nicholas Meyer’s film immediately prior to The Day After, namely Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, where she played Kirk’s ex-wife.

Interesting book I read as a teen was Level Seven by Mordacai Roshwald, about a missile site where a nuclear war occurs, and the officer, on Level Seven, realizes he and those with him are the only survivors, and they cope with that as radiation seeps down to the other levels. He dies of radiation sickness playing Beethoven’s Eroica, then decides no, it has to end and not outlive him…but he dies just as he is ready to switch it off.

Pretty powerful. I tried to write a play about it in high school, but passion was greater than art.

I think the way to understand the nuclear build-up is that there was the Cold War paranoia, but it was also a lucrative business cranking out nukes. It was a weapon no one thought about actually using…like most of our high-priced military hardware is today. Lots of contracts, jobs, cushy bonuses, but war? Naw.

A curious thought now is how effective most nuclear missiles are these days. It’s been almost two generations since they were built, and underground testing has been banned, so no one really knows if they’ll work. Most of the electronic systems are probably rotting, and I imagine maintenance and upkeep isn’t that great.

Like I said in The President’s Analyst, all that brand-new sixties stuff eventually rotted away, and why should nukes be any different?

For fun there is also The Atomic Cafe, a satire on the ‘Bomb’ culture. A funny part is where a priest talks about the moral justice in denying your fallout shelter to people who aren’t Catholic. It’s real.

“Threads” was a long-time favorite of mine, having downloaded it as a teenager in 2005 when 80’s movies were experiencing a minor revival and post-apocalypse flicks were all the rage (starting with the zombie flick 28 Days Later which I must’ve seen a dozen times back then).

Nothing makes me sympathetic to Ted Kaczynski like the idea of nukes. They’re technology in its worst form, and we’re stuck with them forever. Mankind is never going to un-learn how to make these things, unless we actually use them and bomb each other back to the bronze age. It’s incredibly uncomfortable to realize that mankind has reached a point it really would rather not have reached, but can’t back down from it. Truly technology itself has a hold of mankind, not the other way around.

Not to mention, aside from their ability to vaporize entire civilizations, nukes have ruined wars forever. Forget mankind ever settling its differences on a battlefield ever again, all you get will be Vietnams over and over into perpetuity.

no offense, but Ted Kaczynski was a cowardly Luddite lunatic who thought that an outhouse was an oppressive technology. I don’t have much sympathy for any utopian worldview that regards noble savages dwelling in some sort of idyllic and superior “state of nature” other than one that is closer to the truth, i.e., where “the life of man is solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

My Dad was a nuclear and aerospace reliability engineer who made the Minuteman missiles work, analyzed nuclear detonations at the Nevada test site, and was later brought in to fix the space shuttle after it blew up. He hated the military but was proud of the deterrent that such tools were built for. Atoms and Rockets can be used for things besides weapons of mass-destruction too. An early childhood memory of mine is watching the Apollo 11 Moon landing on TV.

I just got home from a rare vacation trip after over a year of severe COVID lockdown. Almost 6,000 miles driven by car across various Western states ─ mostly where I either lived myself when my Dad was doing some government contract, or places that my ancestors settled before the American frontier was secure. I visited Custer’s last stand in Montana and the laboratory at Los Alamos, New Mexico where the power of the atom was unraveled. I saw the cave dwellings at Mesa Verde in Colorado where the pre-Columbians lived in their blessed state of nature ─ and many other things.

Technology is truly a gift from the Gods. It is not magic, nor is it some kind of Frankenstein’s monster. Why people think otherwise is hard for me to understand.

Retired General Curtis LeMay remarked at the 1978 Air Power Symposium that he really did not understand the difference between the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki compared to the firestorm raids of Tokyo. They were the same acts of war, just one big bomb versus complicated thousand-bomber raids. LeMay said that this is what soldiers do and that this is what they have always done. He mused that had the Americans lost the war he would have been tried as a war-criminal. He said this not because he did anything wrong as a soldier but because in this case his side would have lost the war.

History has always regarded brutal military acts as legitimate if they are deemed necessary to win.

I do remember the later portion of the Cold War, and in 1983 I was in the Army Reserve while going to school. I had nothing against the Russians but I supported Reagan’s hardline stance against the Commies, and I was ready to deploy if necessary. The threat of nuclear war was real enough but hugely overblown in my opinion. It was about as likely as an impact of an asteroid like the one that killed the dinosaurs.

I found the movie The Day After to be maudlin propaganda of a rather insidious learned-helplessness variety. I can’t remember too many details about the show now, but I do know as a former electronic technologist with experience in the Army Signal Corps that nuclear electromagnetic pulse does not work the way that they portray it in the movies.

Sure, nuclear war itself is “unthinkable” but so is falling into Fat Larry’s cesspit or a molten pit of lava ─ or getting rained on by white phosphorous at Hamburg or Dresden during the war. The unthinkable is bad, but even worse is to not be prepared for the unthinkable at all.

I lived in Idaho in 1976 when the Teton Dam broke and the towns beneath it were hit by a wall of water. It could have been a Red Cross repeat of Hurricane Katrina but Rexburg, Idaho is nearly all White, and the Mormons actually prepare for disasters such as this by storing food and other supplies. It looked like a war zone with Huey helicopters zooming everywhere. We did a lot of sandbagging at the powerplant at Idaho Falls.

Anyway, the year 1983 was the pioneer centennial of Rexburg, where I was going to school, and earlier in the year President Reagan had announced his “High Frontiers” strategy. This seemed to be too aggressive so it was quickly renamed the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), which the press promptly dubbed “Star Wars.”

The SDI idea was that instead of relying upon a Strangelovian concept of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) all that aerospace technology could be applied to actually shooting down incoming ICBMs. Hmmm, thinking past the Maginot Line, what a novel idea.

The MAD doctrine had eschewed the concept of anti-missile missiles (then using a nuclear burst at altitude to destroy incoming ICBMs) because it increased the uncertainly of “assured” destruction in the event of a nuclear exchange. The Leftists and the game-theory people, most of whom have never dug a foxhole or donned a chemical suit and gas mask in triple-digit temperatures in their lives, acted as if strategic deterrence was something new. The wanted assurance that nuclear energy meant no survival. Unfortunately we are still plagued with that nonsense and it keeps clean nuclear energy mostly off the market.

Anyway, NATO was worried about the numbers of Warsaw Pact tanks which would likely not be stoppable without using tactical nuclear weapons (aka “neutron bombs” because they are small yield and capitalize upon the burst of atomic radiation rather than the blast). In 1983, the U.S. Army was in the process of deploying theater-range Pershing II missiles in West Germany, and the locals were none too happy about it. That year Bundestablishment police and Commie peace creep protestors were beating each other bloody in the West German streets.

If I were German I would not have wanted American nuclear missiles based in my country either, but it did provide a good deterrent against an invasion by Soviet armor and other such mischief. Notably, the Soviets never lifted a finger when the Berlin Wall came down in 1989. I would never say that SDI or Reagan “won” the Cold War, but these things and more at least got the Soviets to the strategic weapons bargaining table, and soon they were talking about Glasnost and Perestroika. Nobody then expected that the Soviets would just decide one day that they would not continue the technological arms race.

Reagan’s people had already decided to replace the Evil Empire concept with what we now call a Global War on Terror, and accordingly he sent Marines into Beirut for a photo-op. They were not prepared to actually fight and the result was catastrophic. I liked Reagan’s firm anti-Communist stance, but not the idea of more small stakes colonial no-win wars for Israel. If it matters, the Gipper did not get my vote in 1984.

Btw, I have visited the Trinity atom bomb test site and picked up the green radioactive shards of glass formed in the fireball on the New Mexico desert sand one July morning in 1945. The so-called Trinitite glass is worth quite a lot to jewelers but you are not allowed to take any of it home with you as it is deemed to be stealing government property. They open up the Trinity site to public visitation in the Spring and Fall every year that isn’t a plague year. At the missile range gate you see sad Leftists protesting nuclear weapons. I wonder how they would have fared in pioneer times.

🙂

I remember that one. I also remember the panel afterward. I walked out when Elie the weasel said something to the effect of, “It’s like the whole world turned Jewish.” The self-absorption just floored me. What a way to win hearts and minds, dude!

<blockquote>These days, a nuclear war seems only slightly more probable than a zombie apocalypse</blockquote>

A nuclear war involving the US is more likely than ever. Jews and the low-IQ “conservatives” who serve them don’t accept the fact that China, a country Jews do not and will not ever control, has become the world’s leading power or that Russia, a country for which Jews have a special hatred, has become resurgent. That’s why the ZOG regime is constantly antagonizing those two countries over Taiwan, Crimea, and other inane pretexts.

What was the mini-series where the Soviet Union occupied the United States? It was supposed to be the answer to The Day After. It depicted statues being torn down, and ballerinas not getting the position they deserve because of quotas, and a bizarre dance number called “I’m the New Miss America.” Huge posters of Karl Marx and Abraham Lincoln were everywhere. I remember seeing previews for it on cnn, the Crossfire show with Patrick Buchanan. Sam Neill was in it. This is pretty much what we have today, only much worse. The Soviets had peculiar ideas about biology but they never thought men could become pregnant or have periods.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment