My Fair Enemy: Pitched Battles & Love Affairs with the Worthy Opponent, Part 1

Kathryn S.Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here)

There is a wonderful Ridley Scott film from 1977 called The Duellists, based on a Joseph Conrad short story, “The Duel.” It follows the exploits of two hussars in Napoleon’s Grande Armée as they traveled from 1800 Strasbourg, to 1812 Russia, and back again to France after Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo. Were their enemies the Prussians, or the Russians, or the British? No, their true enemies were one another — Lieutenant Feraud and Lieutenant D’Hubert, drawn together by pride and an increasingly twisted sense of honor into a half-dozen dueling episodes across nearly two decades, several regimes, and an entire continent. Their obsession symbolized the manias of an age; their murderous meetings the volatility of an empire, and how that Western literary icon, the Worthy Opponent, could consume men’s lives the way only a great love-hate story can.

Valentine’s Day is approaching, readers. We have a day for lovers, why not a day for haters — of the worthy sort? For who can arouse our passions quite like an enemy? Who can desolate our lives of purpose quite like an archrival leaving the field, or dying before we are truly ready to say, “Goodbye?”

Like Feraud and D’Hubert did, we love our families, the wonders and terrors of the natural world, our small corners of the Earth where we live across from our neighbors; we love authority and order, the contests that give men opportunities for honor and distinction. We adore our lovers, wives, and husbands. On good days, we even love ourselves. We also occasionally hate all of these things and all of those people. Sometimes, they disgust us. While using the subjects of brothers, neighbors, Nature, lovers, state, and self, let’s explore how hate has sometimes made the heart grow fonder.

Blood over Water: Imperialists & Barbarians

Few relationships have been more fraught than that shared by imperialist and native — even in ancient times. Although the truth is not certain, there is reason to believe that the three general races mentioned in Greco-Roman writer Luciano de Samosóta’s Hermotino (ca. 120 AD) were

- ξαvθóς, roughly translated to “white” in ancient Greek, and this word the Greeks used to refer to themselves and to those most like them living in the Greco-Roman world;

- μέλας was “black,” or “Ethiopian”; while

- λευκóς meant “yellow,” which likely referred to those northerners possessing blonde/red hair, not necessarily to people from Asia (referring to East Asians as “yellow” only became widespread during the early-modern period).[1]

This is not to say that Greco-Romans considered northern Europeans to be as alien or as dim-witted as blacks from Africa; only that the concept of “Europe” and “Europeans” had not matured by the time of Socrates or the Scipios. There were the old and venerable civilizations located near the Mediterranean, and then there were “barbarians” beyond and north of it — barbarians that, neither Roman nor Greek texts failed to mention, were different. Physically, they were taller, broader, and with fairer hair, eyes, and skin tone.

As in any empire, there were demeaning metropolitan references to the “natives” — to the Teutonic and Gallic peoples of central and northern Europe. But such texts were hardly without instances of admiration for these tribes (nor were they free from criticism of their own Roman societies). Cassius Dio’s account of the British Boudican revolt praised Boudica for her “uncommon intelligence” and mass of tawny hair that flowed down to her hips. Holding a spear with a “terrifying” aspect, the noble British woman argued that her people had “been deceived by the alluring promises of the Romans, yet now” that they had tried both, they had “learned how great a mistake” it had been “in preferring an imported despotism to [their] ancestral mode of life.” Why be slaves, Tacitus asked through the lips of this “barbarian” leader, to the Emperor Nero, “to a bad lyre-player?”[2]

With perhaps respect toward the Germans and distaste for the multicultural Roman metropolis, Tacitus wrote that the “Germans [were] aboriginal, and not mixed at all with other races through immigration or intercourse.” But this purity was a backhanded compliment, for he reasoned, “who would leave Asia, or Africa, or Italy for Germany, with its wild country, its inclement skies, its sullen manners and aspect, unless indeed it were his home?” Unlike the pleasant and beautiful Italian coasts, Germany offered no alluring prospects to foreigners. However “sullen” they were, the Teutonic peoples were valiant, carrying away the bodies of their slain even after losing engagements. To abandon one’s shield was for them the basest of crimes. As for their women, they were no less warlike and “to every [German] man [they were] the most sacred witnesses of his bravery . . . his most generous applauders.” The warrior brought “his wounds to mother and wife,” who did not shrink “from counting or even demanding them and who administer[ed] both food and encouragement to the combatants.”[3]

For their part, the Gaulish and Germanic groups had much to appreciate and much to abhor about their Roman conquerors. In the one-and-a-half centuries between the triumphs of Hannibal and those of Julius Caesar, two-million Gaulish men were cut down by Roman steel, dooming “autonomous ancient France, whose manhood was systematically destroyed in battle as no other people would be in the entire history of Western” imperialism.[4] Caesar’s “pacification” and annexation of Gaul was extraordinarily bloody and brutal. There were hard feelings. But the Romans brought other things besides the sword and the slaver’s lash: order, paved roads, cities, bathhouses, and aqueducts made of stone and marble, as well as desired trade and access to an entire empire of goods, education, and acceptance for the sons of important Gallic and Teutonic chieftains. There were many who acceded to reality and even embraced their captors as adopted fathers. Thousands of young foreign men joined the Roman army.

You can buy Collin Cleary’s Summoning the Gods here.

This love-hate affair with Rome was perhaps best illustrated by the story of the two sons of Segimerus, a chief of the Germanic Cherusci tribe. Arminius and his younger brother Flavus were given over to the Romans as hostages from an early age and sent to live in the Italian capital, where they learned Latin and became, to all appearances, loyal Roman citizens. Arminius served as an equite (or knight) in the Roman army for five years before he returned home to aid Publius Quinctilius Varus, the provincial governor charged by Emperor Augustus with completing the conquest of Germania Magna. Arminius would be his local linchpin; the spy and agent who could bridge the Roman-German divide and convince his father’s people to bend the knee to Caesar. Instead, Arminius decided that blood was thicker than water. He managed to cobble together an alliance of mutinous German tribes under Varus’ nose. By that time, Arminius knew the ways and tactics of the Roman legionary army; knew what movements and paths through the woods they would take; and knew the arrogance of his commander.

Imagine now the specter of the primeval German forests for the average Roman legionary, whose strengths lay in a certain kind of fighting: facing the enemy in the open field and in lines of disciplined formation, protected by shields and gladii. But moving one-by-one along winding footpaths and over a needle-strewn floor of gnarled roots catching at their toes and slowing their horses? Marching along while the gloom became a growing, weighty thing that pressed upon their backs, and where the limbs of Teutoburg Forest were woven so thickly that the wind that plowed across the northern sea could make not even the barest of sighs through its murk? It was the perfect place for an ambush. Bands of German warriors fell upon the disbursed, thin line of the three Varian legions as they attempted to detour through the wilderness during an early autumn rainstorm. This was how an “army unexcelled in bravery, the first of Roman armies in discipline, in energy, and in experience in the field,” was surrounded and “hemmed in by forests and marshes and ambuscades; it was exterminated almost to a man by the very enemy whom it had always slaughtered like cattle.”[5]

Varus, following the example of his father and grandfather, ran himself through with his sword when it became obvious that he had met with total defeat. Other prefects proposed “surrender, preferring to die by torture at the hands of the enemy than in battle.” Vala Numonius, a lieutenant of Varus, “also set a fearful example in that he left the infantry unprotected by the cavalry and in flight tried to reach the Rhine with his squadrons of horse.” But the gods avenged his cowardice, “for he did not survive those whom he had abandoned, but died in the act of deserting them.” The body of Varus, erstwhile mentor of Arminius and negligent governor of Roman Germany, was “mangled by the enemy . . . his head then cut off and [sent] to Caesar.”[6]

Hermann [Arminius] Celebrating Victory after the Battle in the Teutoburg Forest, Johann Heinrich Tischbein, the Elder, ca. 1760

The one righteously extolled “the greatness of Rome, the resources of Caesar . . . and the fact that neither Arminius’s wife nor his son were treated as enemies”; while the other fervently made the “claims of fatherland, of ancestral freedom, of the gods of the homes of Germany, of the mother who shared his prayers, that Flavus might not choose to be the deserter and betrayer rather than the ruler of . . . his own kin.”[7] Here was the passion-play of love and hate for Rome felt by the ancient Europeans. It was fitting that this duel of blood and water between blood-brothers was separated only by the waters of a muddy river. Even this “would not have hindered them from joining combat,” had not their friends pulled them away from its edges.

This double-sided ardor for Rome, this nationalist enmity and imperialist veneration, has since its collapse caused many an ambitious European leader or dynasty to explicitly claim a Roman legacy. Even — especially — in those places that waged such a fierce blood-feud with the Caesars.

Loathe Thy Neighbor: East & West, North & South

No one has inspired the kind of devoted spite quite like the bad neighbor has. More than a century-and-a-half after their rift, Kansas and Missouri have still not mended their fences. By the time of Alexander’s rule in the third century BC, it seemed that the Hellenic cities had similarly not forgiven the Persians for their invasion of Greece during the fifth century BC. When Darius III wrote to Alexander asking the young conqueror for a truce, Alexander would have none of it. “Your ancestors invaded Macedonia and the rest of Greece and did us harm although we had not done you any previous injury,” he retorted. It is not I, he argued, who is the aggressor, for “I have been appointed commander-in-chief of the Greeks and crossed into Asia . . . with the aim of punishing the Persians” for these old wounds. But recent outrages also impelled Alexander across the sea. “You,” he accused Darius, “gave support to the people of Perinthus, who had done my father [Philip] harm . . . [he] died at the hand of conspirators instigated by you, as you yourself boasted to everybody in your letters . . .” Having defeated Darius in battle, killed or captured his satraps and generals, it was Alexander who controlled the country. As such, he wrote tartly, “Approach me therefore as the lord of all Asia,” and do not address me as an equal, “but state your demands to [me as] the master of all your possessions.”[8]

It seemed that there was no love lost between the two kings who had been glaring daggers at each other across the Aegean for years. But Alexander was quick to assure Darius that his captured wife, children, and mother would be accorded all honors due to royalty. When he learned of Darius’ death months later, he cried out in pain and grieved as if for a dear friend. Upon seeing the dead Persian, Alexander “unfastened his own cloak, [and] he threw it over the body, covering it.” Later, he captured the man who had murdered his enemy and decided to punish the assassin. Alexander had the tops of “two straight trees bent down so that they met near the ground. . . part of the [king slayer’s] body was tied to each.” Then, when the trees were “let go and sprang back to [their] upright positions, the part of the body attached to [them] was torn off by the recoil.” As for Darius’ body, Alexander cleaned, oiled, and “returned it to his mother” for the purpose of laying it out in royal state.[9] This was the proper treatment, not for an odious neighbor, but for a worthy opponent. There is something touching about male chivalry that this woman hopes has not passed from the West.

Similar instances of white-hot hate and respectful gallantry characterized the American Civil War and its long aftermath. By late April 1865, the Confederacy at its best “had the look of a deserted fairground. But for the most part, the sights and colors [were] ugly, even ungodly.” In fact, the only way to appreciate the full devastation of the region is to, in the words of one historian, “reverse the names.” Imagine New York, “burned to the ground”; Boston, torched; Philadelphia, the same; Chicago and Washington, likewise. Add to the list: “Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts; and Rye, New York; and New Haven, Connecticut.”[10] Don’t leave out Newport, Rhode Island, and Old Westbury, Long Island. Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, also turned to

a veritable wasteland; Baltimore, Maryland, and Wilmington, Delaware, occupied; Fifth Avenue, barren. West Point ransacked and set ablaze; the New York Times and the Boston Globe and the Baltimore Sun, shut down. And Princeton and Yale, closed; Central Park, Manhattan, a national graveyard; Tiffany’s, a burned-out shell; Niagara Falls, a blackened ruin; the New York City Public Library, trashed; Wall Street, worthless.

Diarist Mary Chestnut meanwhile shivered at General Sherman’s plans for South Carolina: “We are going to be wiped off the face of the earth!” she cried, and well she might have. The burning of Atlanta was just the beginning of his wrath. A visiting Mrs. Munroe took up Chestnut’s photograph book, in which she had a picture of all the Yankee generals. “I want to see the men who are to be our masters,” Mrs. Munroe said. “Not mine,” Mary answered passionately, “come what may!” No, this was a free fight. “We had as much right to fight and get out as they had to fight and keep us in. If they try to play the masters, anywhere on the habitable globe will I go, never to see a Yankee, and if I die on the way, so much the better,” she stormed.[11] Then, with charity toward none, Mary sat down and proceeded to write her husband a letter using language worse than anything she could include in a published memoir. The idea of reconciliation with those Damnyankees seemed not only laughable, but loathsome.

But there were signs that even in the midst of total war waged by the victors there could be respect, even affection, for the fallen. “I have probably to be Grant’s prisoner today,” General Robert E. Lee mused as he dressed in his spotless uniform to go and meet his conqueror at Appomattox Courthouse. The two men could not have been more different as the literal manifestations of North and South. The one was romantic and glamorous, even in defeat: the tall and stately Lee, scion of an old colonial house; a tragedian. Men gladly died for him. Then there was Ulysses Grant, stubbled and frumpy no matter what he wore: a man much closer in spirit to the nineteenth century and the coming wave of capitalism, of “speculators, doers, and party men;”[12] a utilitarian. But having triumphed over a valiant enemy, Grant refused to destroy his dignity. He allowed Lee to choose the time and place of their meeting, then rode the 16 miles to Appomattox, his nerves making him feel as if he were a schoolboy again, about to face the headmaster. To break the ice, he spoke about having met Lee once before during the war in Mexico, when the older man rode from General Winfield Scott’s headquarters over to the brigade in which Grant belonged. “I have always remembered your appearance, and I think I should have recognized you anywhere,” the younger man confessed. “Indeed,” acknowledged Lee, “I know I met you on that occasion, and I have often thought of it, and tried to recollect how you looked, but I have never been able to recall a single feature.”

The Union General tried to make light conversation for a time, as if avoiding the moment when he would have to force the other man to acknowledge the fact of his defeat — as if it embarrassed him to do so. “Our conversation grew so friendly,” he claimed, “that I almost forgot the object of our meeting” — until Lee, who never had, interrupted him. And as it turned out, “Unconditional Surrender” Grant’s terms were very generous; he was as courtly as Alexander once was to Darius and his family. Lee would not be his prisoner, nor would any of his officers. The men could keep their horses and sidearms. Once they swore to fight no more, they could leave, glorious in the dust, for their homes. For his part, Lee afterwards never suffered in his presence an unkind word to be spoken about Grant. When the radical Republicans and federal officials began to threaten Lee with arrest, Grant in turn threatened to resign from the military and the party. “I gave Lee my pledge once he signed the surrender,” he explained about his old enemy, “that he would be a free man.”

It was all well and good for generals to wage battle, then make peace. It took longer for everyone else to get over the bad blood. Reconstruction didn’t help. But by the turn of the century, southerners were allowed to praise their native valor and to publish hagiographies about the immortal Army of Northern Virginia. Yankee authors made a profitable industry out of writing bad books and plays about northern soldiers falling in love with southern women, the war-making heightening the excitement of the love-making. These stories ended happily ever after, of course. All was forgiven and the reconciliation of states was represented in the state sacrament of marriage: a romance of reunion. It seemed that the sentimental federals missed the old picturesque antebellum plantation image more than the former plantation owners themselves. So, the late nineteenth century was the Era of Mixed Feelings. Yes, the North got to play the role of manly gallant to the pretty southern belle in the midnight magnolia garden patch, while the South got to cling to its pretty myth of invincibility — that it would sooner or later rise again! A generation after the first artillery crack over Sumter, and the neighbors were finally getting along. Sort of.

Held by the Enemy (1887), a hilariously bad William Gillette play about conflicted love during the Civil War

Man vs. Nature: Facing Mortality and the Terrible Cosmos

Anyone paying attention when reading an ancient epic like Beowulf will realize that the true enemy was never a monster — neither was it Grendel, nor Grendel’s Mother. For Beowulf, it was the thing he most venerated and feared: old age. When battling the beast, or his dam, the “she-wolf of the deep,” the hero felt no hesitation. “So must a man do Who would win long-lasting glory In battle. He must be careless of life!”[13] To die in battle — that was no shame.

You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here.

The “dark-age” Anglo-Saxon tribes in Beowulf (the Geats) were related to and very similar to the Germanic peoples described by Tacitus, those warriors for whom “it [was] a disgrace for the chief to be surpassed in valour, a disgrace for his followers not to equal the valour of the chief.” It was an infamy and a reproach for life “to have survived the chief, and returned from the field. To defend, to protect him, to ascribe one’s own brave deeds to [the leader’s] renown, [was] the height of loyalty.” A prolonged peace for a native state was for them a place sunk into the “sloth of repose.” Many of their noble young men, like Beowulf, would voluntarily seek action, or go searching for those tribes waging some war, both because “inaction [was] odious to their race, and because they [won] renown more readily in the midst of peril.”[14] So, for a chief/warrior to gradually wane in strength to an old age of “repose,” to a peace inflicted on a spent braveheart by the degenerating vagaries of time and nature? By slowed mind and crumbling muscle? Such a fate was intolerable.

And yet, Beowulf heeded, craved the wisdom of old men, and hoarded their words like rubies won from the treasure-lair of a dragon. The old king Hrothgar whose people he’d saved from Grendel’s race kissed his brow. A deep longing for that “dear old man burned in his blood.” May we meet again, the silver-haired King of the Shieldings prayed, though he doubted it. “Dear Beowulf, finest of warriors, In the end it must come to pass That the body . . . fails . . . You’ll glory in strength,” for a time. But soon sickness or sword “Will weaken your powers, a flare From the fire, or the flood’s surge, Or blade’s leap, or spear’s flight, Or foul old age” will take away the joy of your days. Even “The brightest eye Darkens and dims. Warrior, soon Comes Death over-sweeping you.”[15] Though Beowulf eventually died having fulfilled his house’s expectation of glory and courage — after facing the dragon-worm and breaking his sword upon the serpent’s skull — he mourned “That he had done with his length of days.” Having ruled his people for 50 winters, he was an old man. He regretted at last that he had not fulfilled Nature’s great call: to have produced an heir and “given [his] son [his] war-gear.” A woman at his funeral “wove a death-dirge,” singing that with the wind scattering the ashes of his pyre had gone their great protector. The fate she envisioned for the Geats was a “mortal dread of the pain that waited, A reign of terror, rape, and unending slaughter.” Like the poem itself, Beowulf’s line had come to an end.[16]

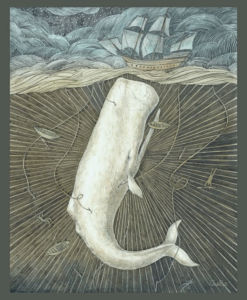

No longer were there white warrior tribes in Western Europe and America by the nineteenth century, but there was still in “every robust healthy boy with a robust healthy soul in him, at some time or other” a craze for adventure — a desire to test himself against other men and the elements.[17] The sea-monster in Herman Melville’s American epic was perhaps even more fearsome than Beowulf’s “mighty mere-wife”: the White Whale. The novel’s central conflict was between Captain Ahab and the malicious sperm-whale Moby Dick, a beast who had bitten off and eaten Ahab’s leg, earning him the hunter’s fierce obsession. Did Ahab hate the White Whale? Did Ahab love the White Whale? Yes, readers. Deeply.

It was that same passion for the sea that many boys felt upon their first voyage out, a “mystical vibration” that took hold when their ships first drew “out of sight of land.” It was the same fantastic chord that caused “the old Persians [to] hold the sea holy,” the reason “why . . . the Greeks [gave] it a separate deity, and [made] him the own brother of Jove.” It was the “same image we ourselves see in all rivers and oceans” — sublime Nature, “the ungraspable phantom of life.”[18] If there were any groups who still carried the Beowulfian-warrior fire of ancient Europe within their breasts, they were the whaling-men who faced the long dark and the infinite deep with only their courage and their sailor comrades to buoy them.

Ahab himself seemed honed and heightened by the forces of Nature. As civilization receded, he finally showed himself to the crew, freed by the lone Atlantic. And as the narrator first glimpsed him, the Captain “looked like a man cut away from the stake, when the fire has overrunningly wasted all the limbs without consuming them.” His whole broad form “seemed made of solid bronze,” cast like “Cellini’s Perseus.” Cutting its way down his face, there was a livid white scar that “resembled that seam sometimes made in the . . . trunk of a great tree, when the upper lightning tearingly darts down it . . . leaving the tree still greenly alive, but branded.”[19] In place of his missing limb, he had an ivory peg-leg made from a whale’s polished jaw bone. As closely as he could, he had made himself into a human version of Moby Dick, made himself into a worthy opponent.

The color white, Melville reflected, has many pleasant connotations: purity and innocence; its aspect, like a string of pearls or a snow-white charger, enhances beauty. But divorced from these, white is Nature’s most terrifying face “which strikes more of panic to the soul than that redness which affrights in blood.” Nor does [Nature] fail “to enlist among her forces this crowning attribute of the terrible.” It is an elusive quality of white that can, “coupled with any object terrible in itself . . . heighten that terror to the furthest bounds.” Sometimes, it is a supernatural shade — a ghastly whiteness. The pallor of the dead. The shroud. The phantom. White “shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation.”

We have here detailed the love and hate of the color — the essence — most central to our movement. As in Beowulf, then, it was not the monster, not Moby Dick who was the real opponent. It was the immensity of Nature, of the whiteness of the Milky Way, of the “no color, allcolor” from which most of us shrink.[20] It was the color Ahab both embraced and hunted with a murderous intensity only quenched by Nature herself when the White Whale dragged him through the foaming, milky waves and then down to the bottom of oblivion.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] See this explanation here from a generally solid Italian historian YouTuber who specializes in ancient Rome and military history.

[2] Cassius Dio, “Speech of Boudica,” 62.3.1

[3] Tacitus, Germania, “The Inhabitants: Origins of the Name Germany,” 2.1.

[4] See Victor Davis Hanson’s Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power (New York: Anchor Books, 2002), 149-150.

[5] Velleius Paterculus, Roman History, 2.119.2.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Tacitus, Annals, 1.59.

[8] Arrian, Anabasis, 3.45.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Jay Winik, April 1865: The Month that Saved America (New York: Harper-Collins, 2001), 363.

[11] Mary Chestnut, A Diary from Dixie (New York: Gramercy Books, 352-353.

[12] Winik, 213-214.

[13] Beowulf, A. S. Kline, trans. (2012), 56.

[14] Tacitus, Germania, “Government; Influence of Women,” 7.1.

[15] Beowulf, 69.

[16] Ibid., 111.

[17] Herman Melville, Moby Dick (1851), 16-17.

[18] Ibid., 134.

[19] Ibid., 193-94.

[20] Ibid.

My%20Fair%20Enemy%3A%20Pitched%20Battles%20and%23038%3B%20Love%20Affairs%20with%20the%20Worthy%20Opponent%2C%20Part%201

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

-

Introduction to Mihai Eminescu’s Old Icons, New Icons

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 1

-

“Few Out of Many Returned”: Theaters of Naval Disaster in Ancient Athens, Part 2

-

“Few Out of Many Returned”: Theaters of Naval Disaster in Ancient Athens, Part 1

13 comments

A worthy opponent appears to be a casualty of modernity.

Towards thee I roll, thou all-destroying but unconquering whale.

Moby Dick (and the Dragon) seem to me representative of the undefeatable forces of Nature and Time in their most terrifying aspects. However, while Nature can destroy all that we hold dear and grind our bones to dust, it can never conquer our spirits. Only man can conquer: first himself and then others.

Nature and Time seem to me unworthy foes in that regard. They will always win the physical battle but will only win the battle over our spirit by proxy – that is, if we lose that battle within ourselves.

Hi, Archie — I see your point. But I would say that man vs Nature is a very ancient and venerable conflict; the fact that we can capitalize Nature and Time is a simple and elegant proof of that, of the respect we have for them. Man often becomes greater by facing those things, honing his “spirit” through trials like sea voyages, mountain climbing, etc. When an antagonist teaches us things, or makes us better, he/it is worthy.

λευκóς meant “yellow,” which likely referred to those northerners possessing blonde/red hair, not necessarily to people from Asia

From Eurasia. They were nomads, horserider peoples from the Northern Black Sea region, the space between the Don/Tanais/Ten and the Volga/Rha/Edil, and further to the East, to the present Eastern Turkestan, Kashgaria, the foothills of the Tien Shan/Tengeri-Taw. First, the Iranian-Aryan peoples, the Scythians, Saks, Sarmatians, later the Türks – from the Huns and Avars to the Kipchaks and Tatars. The last to come were the Jungars-Oirats, who remained on the Volga and became Kalmyks. To some extent, they are all yellow, as they are tanned in the Steppe sun and weathered by the snow/sandstorms of the Great Steppe.

You may very well be right; at times it’s hard to know exactly what the ancients meant, or how to accurately translate their terms. We’re missing a lot of pieces, and so many ancient texts have been lost; one of the greatest tragedies, in my opinion.

Thank you for reading, Mr. Böri.

Kathryn is our Plutarch.

We owe it to her to create a new Plutarchracy.

Cf. Helen-ism

I’ll take it!

Another very enjoyable text, thank you Kathryn.

If I remember well, among all the characters and sub-characters whose lives Plutarch described Lucullus was the only one not dying a violent death

Thank you, Philippe. It does sometimes seem that everyone who was anyone in those days was either headed toward assassination or suicide.

The whole lot of them, women, children…

Or death in battle.

Makes you wonder about human nature, without being pessimistic.

There’s a book that just came out titled: Spare No One, and its central premise is that the Romans had a cold and calculating policy of mass slaughter; it was quite difficult to kill thousands of people at time during the small centuries, so these massacres were not primarily fueled by frenzied blood-lust; they were instead methodical, purposeful.

Whatever that reveals about human nature (we live in a fallen world) , these people did not come to play.

Hi Kathryn, you mention Arminius in your essay and it reminded me of this fairly decent documentary on this man and his achievements. Well worth a watch.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67pyFdzuaJc

Stephen, the Romans certainly had a total defeat like that coming; eventually an aggressive imperial force will try to conquer one people too many; will try to expand one “province too far.” I’m 3/4 of the way through the video, and I like how it emphasizes the terror and alien-ness of the German forests for the average legionary. Thank you for sharing!

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment