Melissa D. Burrage

The Karl Muck Scandal: Classical Music & Xenophobia in World War I

Rochester, N.Y.: University of Rochester Press, 2019

This year saw the publication of a curious little history about a curious little event from the First World War. Karl Muck is a name that might not be on the lips of many people these days. A hundred years ago, however, as the German-born conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) who was interned in a Georgia concentration camp under dubious circumstances, he certainly was. His story offers a sometimes poignant, sometimes baffling glimpse into our contentious political natures. It also presents a startlingly clear mirror image of our current struggles – seemingly identical, yet eerily inverted. In the Muck affair, the inevitability of ethnocentrism is impossible to ignore, yet that’s what author Melissa Burrage tries so hard to do. That she steeps her book, The Karl Muck Scandal, as deep as she can into today’s stifling political correctness only adds layers of irony to this fascinating and mostly-forgotten historical episode.

It seems that Burrage initially approached this project with only a superficial understanding of her subject matter. The subtitle of her work is Classical Music and Xenophobia in World War I America. The dust jacket blurb tips her hand even more (or, more likely, that of her publishers):

One of the cherished narratives of American history is that of the Statue of Liberty welcoming immigrants to it shores. Accounts of the exclusion and exploitation of Chinese immigrants in the late nineteenth century and Japanese internment during World War II tell a darker story of American immigration. Less well known, however, is the treatment of German-Americans and German nationals in the United States during World War I. Initially accepted and even welcomed into American society, at the outbreak of the war this group would face rampant intolerance and anti-German hysteria.

From such vain moral posturing, one can conclude that this book will amount to yet another blunt instrument with which the Left can pummel supporters of President Trump for wishing to build a wall on the Mexican border and limit non-white immigration. If we can shame people for past xenophobia, according to this strategy, perhaps we can conquer xenophobia today and allow the huddled masses of future Democrats to keep streaming into America. (Stephen Jay Gould attempted a similar kind of history-shaming – only with psychometrics – in his thoroughly debunked The Mismeasure of Man.)

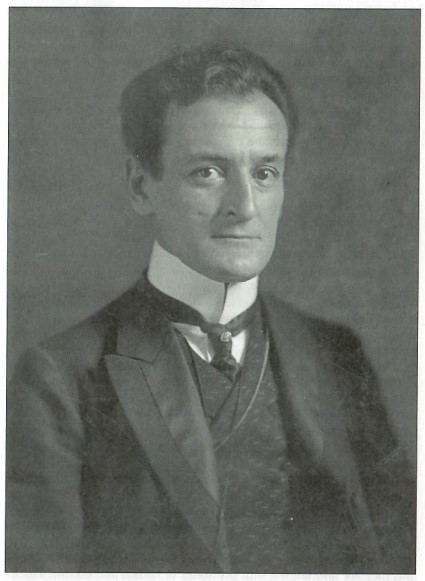

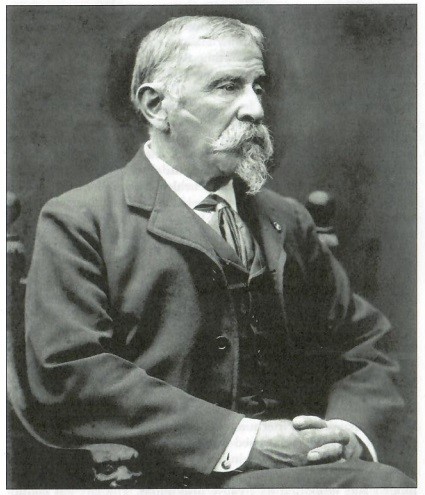

Burrage hits a snag, however, when she reveals Muck’s true character. He was the most celebrated conductor in America at the time. Under his leadership, the BSO became the nation’s leading orchestra, which aided greatly in keeping Boston at the forefront of American high society and culture. Affable, charismatic, and cultured, Muck was extremely popular in Boston, and, shortly after arriving at the behest of financier and BSO founder Henry Lee Higginson in 1906, became a de facto member of Boston’s aristocracy. This aristocracy was so famous, it had a name: the Boston Brahmins. Boston was also home to a very large German population and was ground zero for Germanophilia in New England. German businesses, German newspapers, German food, and German culture were highly visible in Beantown in the early twentieth century. Of course, everybody loved German classical music, which Muck was all too happy to provide.

Higginson was Muck’s biggest booster, despite not being German himself. They were close friends who had much in common, culturally and ideologically. Both were highly aristocratic and conservative. Higginson had spent many years in Germany and Austria in his youth studying piano, and was fluent in German. In a peculiar coincidence, both men had similar scars on their right cheeks. Muck received his from a fencing duel in his youth, and Higginson from a Confederate saber during the Civil War.

But who was Karl Muck? He was a highly educated man of world-class talent who was proud of his German roots, possessed nationalistic sympathies for his nation of birth, and held the realistic opinions on race which were common in his day. This was, after all, the heyday of writers such as Madison Grant, Lothrop Stoddard, and Henry Adams. Race realism, as well as cultural chauvinism and a healthy support for eugenics, were de rigueur in educated circles back then. And this included a relatively mild form of anti-Semitism among the still-strong WASP elites:

[Muck’s] racial views also affected his actions and judgment. When composer Ernest Bloch presented his Three Jewish Poems for inclusion on the Boston Symphony program, Muck was reluctant to debut the work if Bloch did not change the title. Bloch supposedly responded, “Dr. M[uck] you speak exactly like my Jewish friends, who advised me to change the title for obvious reasons.” Bloch defended the title of his piece, to which Muck replied, “If there were more Jews like you, there would be less anti-Semitism.”

Higginson was worse in this regard – or better, depending on your perspective. He supported immigration restriction in order to keep undesirables out of America and was a race patriot almost as much as he was an American patriot. He was a leading member of the Immigrant Restriction League, and was well ensconced in the national power circles of the day, being cousins with fellow immigration hawk Senator Henry Cabot Lodge. Higginson used his contacts in government to bust musician’s unions. He also wrangled with Jewish attorney and future Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who sought to curtail Higginson’s various business interests in the name of trust-busting. And this, according to Burrage, informed Higginson’s negative opinions of Jews.

Not surprisingly, Burrage considers Higginson’s racial views “flawed,” and then describes Higginson and the Immigrant Restriction League like so:

The league also used pseudo-scientific dogma to divide European white men into biological categories, classifying eastern Europeans into the most inferior type to justify their arguments. Its view of nationalism was built on an “ideology of kinship to enthrone their own tribe and oppress others.” It justified discrimination, arguing that America could “improve its race” by selecting immigrants based on “appropriate national origins.” The league was influenced by eugenicist Madison Grant, who wrote The Passing of the Great Race (1916), which promoted a theory of “Nordic” racial supremacy and advocated the separation or removal of all “worthless” and “unfit” types. It was inspired by scientist Robert DeCourcy Ward, who publicized his view that “science decrees restrictions on the new immigration for the conservation of the ‘American race.”’ Higginson‘s father-in-law, Harvard professor Louis Agassiz, was a prolific writer and teacher on the topic of scientific racism, believing that races were distinct and unequal and could be classified based on climatic zones. Boston’s upper classes feared that foreigners would replace their own native stock, and they worried about “biological defeat.” Immigration restriction was a “phase of national defense” against “the strange invaders who seemed so grave a threat to their class, their region, their country, and their race.”

After stepping back from this and having a cigarette, I believe most of us on the Dissident Right will conclude that we were all born a century and a half too late.

Getting over that, there is so much to unpack here, one hardly knows where to begin. Yes, there’s the stunned respect we all must have for this Higginson fellow, who was related to both Henry Cabot Lodge and Louis Agassiz (whom Gould heartily denounced in Mismeasure), and who was able to speak in defense of white, ethnocentric interests so candidly. The Boston Brahmins had every reason to worry about biological defeat; we’re entering the jaws of that defeat today. Also, this passage should be met with some sadness regarding the hidebound chauvinism whites used to have toward other whites. This attitude will have to be discarded entirely for whites to have enough solidarity to thrive in the next century.

Most apropos to The Karl Muck Scandal, however, is how Burrage attempts to paint Karl Muck as the victim of xenophobia. Of course, he was. He was a perfectly innocent man when federal authorities arrested and incarcerated him in March 1918. But Muck and Higginson were Dissident Rightists back when the not-so-Dissident Right ruled the roost in America. So Burrage is in effect going to bat for someone on the Right in order to strike a blow for the Left. How’s that for irony?

The story undergoes a few more twists before completely unraveling. If there is a villain in this book, it is New York socialite Mrs. William (Lucie) Jay, who really didn’t like Germans. Jay, whose deceased husband was descended from early American statesman John Jay, tirelessly lobbied for Muck’s dismissal from the BSO all throughout the war. Muck hired too many German musicians, or he played too much German music, according to her. The woman organized committees to ban all German music. She tried to prevent the BSO from playing in New York. She spread false rumors about Muck in order to discredit him. She hurled insults at him as often as possible. She called for boycotts. She accused him of supporting the German military effort. She also (ahem) muck-raked his life, searching for sexual impropriety. As anti-German feeling in America grew more and more intense, Jay’s attacks on Muck grew more and more strident.

Here she is at her hysterical best:

Rather a thousand times that the orchestral traditions fade from our lives than one hour be added to the war’s duration by clinging to this last tentacle of the German octopus!

Then there was the “Star-Spangled Banner” non-scandal which got the attention of the entire country. In October 1917, the BSO had received numerous requests to play the “Star-Spangled Banner” before a concert in Providence, Rhode Island. Since it was late and the programs had already been printed, Higginson decided to ignore the requests. The song hadn’t yet become the national anthem (which wouldn’t happen until 1931) and didn’t quite fit in with the pieces the BSO was slated to play that evening, anyway. Of course, Higginson didn’t bother to tell Muck about this, and allowed the oblivious maestro to conduct a concert free of star-spangled banners.

In an astonishingly brazen instance of “fake news,” John Rathom, the editor of the Providence Journal, then accused Muck of deliberately refusing to play the patriotic anthem because of his German sympathies. Not only did this story later appear in newspapers all across the country, but Rathom kept the momentum going with even more accusations:

The zealous newspaperman spread reports among his readership that Muck was pro-German and a friend of Kaiser Wilhelm. Rathom distorted the facts, claiming to uncover foreign espionage plots that were later revealed to be fraudulent. Once such plot suggested that Muck intended to destroy American munitions factories. On November 21, 1917, the New York Times reported that Rathom “thrilled and enthused” seven hundred members of the Pilgrim Publicity Association at the Boston City Club with a story of “German spies in Boston” outlining his great campaign against them.

This damaged Muck’s reputation overnight, and Lucie Jay later used it relentlessly to incite violent hatred against him. (Burrage speculates that Jay and Rathom colluded in Muck’s character assassination, but no one knows for sure.) Thousands of influential Americans were now onboard Lucie Jay’s muck-up-Muck train. People were calling for the conductor’s assassination, internment, or deportation. Crowds as far away as Baltimore were chanting “Kill Muck! Kill Muck!” It got so bad that the authorities had to step in to determine if Muck was indeed a dangerous enemy alien. In all cases, they found no evidence of wrongdoing – but not for lack of trying. Some investigators feared that Muck was putting coded messages in his musical scores. Others theorized that he kept a disassembled radio transmitter in his Maine summer house with which he signaled German U-boats. (The apparatus belonged to the landlord, and was unbeknownst to Muck.)

Regardless, we should remember that this was a period when the American war machine was churning out absolutely vicious anti-German propaganda – and the people were beginning to believe it and take part in the suppression of all things German. Violence against German-Americans became quite common during this time. So these false accusations from Jay and Rathom threatened to have deadly consequences.

Despite her hypermodern moral posturing, Burrage does provide useful scholarship. Most notable in The Karl Muck Scandal is her well-researched contention that Lucie Jay was not all that she was cracked up to be. Jay may indeed have been an American patriot. She may also have been as anti-German as advertised. But her real motivations behind ruining Karl Muck’s life were far pettier. She was on the Board of Directors of the New York Philharmonic (NYP), and was jealous of the BSO’s star conductor. Other than the brief period from 1909 to 1911, when Gustav Mahler waved their baton, the Knickerbockers really did play second fiddle to the Celtics back then – and that bothered a lot of wealthy and powerful people in Gotham. Taking out the NYP’s top rival in the most literal sense became Lucie Jay’s idée fixe throughout the wa,r and ultimately made her the Tonya Harding of classical music.

Burrage reveals another reason for Jay’s hatred for Muck, and this one’s even pettier. Yeah, it was all about money:

Jay had even deeper motives for her persistent attacks on the Boston Symphony that cut to the heart of her own economic security. In September of 1906, her brother Hermann had passed away. Estranged from his wife, much of his estate was bequeathed to Mrs. Jay and her brother Charles. Mrs. Jay acquired a large share in the North German Lloyd Steamship Line and presumably railroad stocks from the Vanderbilt interests as well. It made logical sense to support her family’s interests and further their progress within the United States, which was threatened, as we shall see, by political forces directly related to the BSO.

And what were these political forces? None other than Henry Lee Higginson and his powerful anti-immigration allies in government. Since the 1880s, millions of immigrants, many of whom were Eastern European Jews, had been streaming into America from Europe on steamships, making Mrs. William Jay and her family richer and richer by the mile. Immigration was Mrs. Jay’s bagel and cream cheese, as it were, and Higginson with all his race realism and polite anti-Semitism was threatening to spoil the bar mitzvah. That’s basically it. So, let’s now appreciate another level of irony in which Burrage is forced to cast a pro-immigration harpy like Jay as the villain in a drama that’s ostensibly pro-immigration.

Unbelievable as it sounds, there’s even more irony to this story. Lucie Jay, as it turns out, was herself German! Her maiden name was Oelrich – a fact she obscured beneath her husband’s time-honored and quite Anglo last name. It seems to me that the obsession behind Jay’s Muck-hate was a form of ethnocentrism in reverse, the kind of contempt born only from familiarity. I can’t prove this, but it seems to be the prime motivator here. America was pulled into a war with Germany, and Jay felt especially betrayed by her own people whenever they expressed sympathy for the enemy. And in Muck’s case, this was at least half-true. Before America’s entry into the war, he had actively supported his homeland and was on excellent terms with the German ambassador in Washington. He also never applied for American citizenship and never denounced Germany. For a person like Lucie Jay, who wanted to erase or hide everything about her that was German, what Karl Muck did (and did not do) must have seemed like treason.

The story could have ended here. Worn down by years of slander, libel, hostility, and death threats, Karl Muck and his wife Anita decided to leave for Germany. He resigned from the BSO in March 1918 and was preparing to depart when he was hit with the bombshell news that the Massachusetts District Attorney would not let him leave. Apparently, the DA was intrigued by Lucie Jay’s previous unproven accusations of sexual impropriety, and felt that Muck may have a skeleton rattling around in his closet after all. And after a thorough investigation by the Bureau of Investigation (BOI), they found it. Muck had been having an affair with a 22-year-old mezzo-soprano named Rosamond Young.

This wasn’t a mere summer fling; he was madly in love with her, so much so that he wrote her love letters and promised to divorce his wife for her. Yes, he was a married man in his late 50s. Yes, under normal circumstances, this would be quite the scandal. But it hardly amounts to law-breaking. Yet the BOI and powerful anti-German elements in the federal government – especially hardline Attorney General and rabid Hun-hater A. Mitchell Palmer – were determined to make it so. And under what contrived pretenses did they finally nab Muck?

Well, Muck (kind of) violated the Comstock Act of 1873, which forbade sending anything obscene or immoral by US Mail. Apparently, sappy quotes such as this qualified as “obscene”:

But can’t you see, my darling, how much harder it is for me to renounce the love that grew between us so sublimely? Must we, for the sake of foolish sentiments that are imposed on us by others, foreswear the love that is divine and inexpressible by common language? No, a thousand times, no! You are mine and I am your slave and so I must remain.

He also (sort of) violated the Mann White Slavery Act of 1910, which prohibited transporting women or girls across state lines “for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” Muck had apparently “abducted” Young every time he traveled with her out of state with the BSO to perform.

Such flimsy reasons to arrest a man may seem ridiculous today, but they were deadly serious back then. Yes, the US government needed to keep a lid on the immoral behavior of its citizens (if only it would do so today!), and yes, white slavery was quite the menace back then. However, Karl Muck’s arrest clearly amounted to abuse.

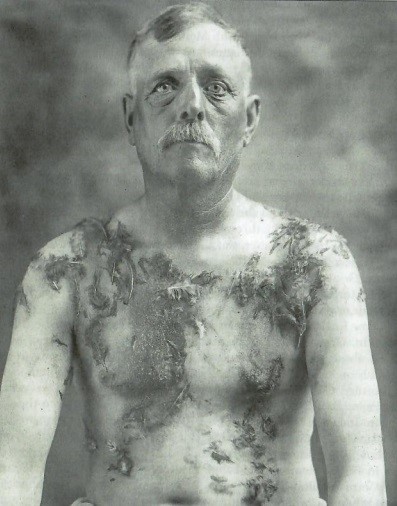

And the abuse did not end there. American authorities then blackmailed Muck into being interned as an enemy alien at Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia in return for their keeping quiet about his affair with Young. It was either that or going public and trying him as a sexual deviant in a Boston court – a humiliation that would ruin him, Young, and Anita regardless of the trial’s outcome. Honorable gentleman that he was, Muck “was only too proud to shoulder” the burden of internment, and opted for the extended vacation in Georgia. He stayed there for a year and a half.

Then, while Muck was serving time behind barbed wire and machine guns in the sweltering Georgia heat, the US government reneged on its promise and allowed the Boston press to publicize his affair and his love letters to Young anyway. This caused nearly all of what remained of Muck’s fan base to abandon him. The Boston Brahmins did so as well, likely because distancing themselves from Muck would keep the heat off their own sexual indiscretions, of which, according to Burrage, there were many. Unfortunately, Higginson was counted among this number – although in his case he seemed to be acting more out of wartime American patriotism than sexual hypocrisy.

If this weren’t enough, the US authorities then stole all of Muck’s assets. When they finally deported him nine months after the war, he went back to Germany flat broke.

Well, after this disgraceful episode, an embittered Muck had had enough of America. Not surprisingly, his own ethnocentrism began to flourish once he was back home. He jumpstarted his career in Bayreuth with help of the Wagner clan and became very close to them, especially with Wagner’s widow Cosima. After poor Anita’s death from cancer in the early 1920s, Muck was able to reassert himself as a world-class conductor. According to Burrage, he produced original interpretations of Wagner by pouring all the pain from his recent tragedies into the great composer’s work.

It was through the Wagners that Muck met an up-and-coming young radical named Adolf Hitler. The two got along famously and remained friends for the rest of Muck’s life. And it wasn’t only for their shared love of Wagner’s music. According to Burrage:

Karl Muck’s ultraconservative nineteenth-century view of the world was compatible with Hitler’s thinking. Old German elites like Muck were keen to maintain stability and order, and he found enough common ground with Hitler to admire him. Muck’s elitism, his sense of German superiority, his anti-Semitism, and his anti-communism, all were in alignment with Hitler’s Nazi ideology.

Even before Hitler came to power, Muck was not shy about blacklisting or simply not hiring Jewish musicians. Afterwards, he fired them at Hitler’s request and claimed that only the under the most extreme circumstance would he ever bite from “the Jewish sour apple.” When he finally resigned for good in 1934, he made it clear that he wasn’t doing it in protest of Hitler’s treatment of Jews.

Hitler showed his love for Karl Muck by naming the square in front of the Hamburg Music Hall after him and by awarding him with the coveted Eagle Shield medal on Muck’s eightieth birthday in 1939. In a more touching gesture, he also named his dog after the conductor:

If the Karl Muck episode can teach us anything, it’s that we cannot beat our inner natures. When we are placed under pressure, for example, during times of war and deprivation, or even during the onset of old age, we tend express our true selves. We cannot help it. Burrage blithely accuses Americans of “xenophobia” towards Germans during the First World War, but if Americans had been truly xenophobic, they would have been anti-German before the war as well. But they weren’t. Just the opposite, in fact. Total war can do strange things to a person’s mind, causing him to hate what so recently he had loved. Henry Lee Higginson provides an excellent example of this. He was, deep down, an Anglo-Saxon, and his inherent and quite natural ethnocentrism ultimately trumped his love and admiration for the German Karl Muck and all the beautiful high culture he stood for. Muck himself may have been dismissive of Jews while in America – but he still worked with them, most notably violin virtuoso Fritz Kreisler. It was only afterwards in Germany, when he was surrounded by his own people and had absorbed their sense of national pride and identity, that he finally acted on his ethnocentrism against Jews.

Wouldn’t it be better if we expected and encouraged people to be ethnocentric to begin with rather than wait for war or tragedy to make a mess of things, forcing them to be that way?

In August 1914, Muck was actually in Germany for a performance and was reluctant to return to the BSO out of nationalistic sympathies for Germany in its time of crisis. He also correctly feared there would be anti-German backlash in the United States. Higginson talked him into returning regardless and promised to protect him, come what may. Muck then risked his life on a dangerous sea voyage back to the States in order to fulfill his obligations to Higginson, the BSO, and his multitude of fans. That he was ultimately rewarded with incarceration, humiliation, and poverty should stand as a reminder that when the chips are down, we should all remain with our own.

The%20Karl%20Muck%20Scandal%3A%20A%20Study%20in%20Ethnocentrism

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

On Second World War Fetishism

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 1

-

National Socialism as a Magical Movement: Stephen E. Flowers’ The Occult in National Socialism

-

Communist Barbarism in Hungary — and America Today: When Israel Is King

-

Introducing a Reactionary Aphorist

-

The Man of the Twentieth Century: Remembering Ernst Jünger (March 29, 1895–February 17, 1998)

2 comments

Could this be whence the phrase, “Mucking it up!” originated?

Fordham Smith’s all-too-obvious prejudice against Burrage mars this otherwise thorough review of a truly great book.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.