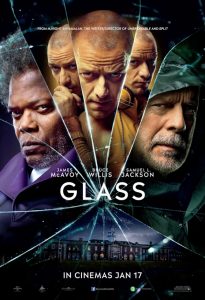

M. Night Shyamalan’s Glass is a sequel to two of his films, Unbreakable (2000), which is my favorite of his works, and Split (2016), which I found to be quite unpleasant, although I must concede that it is brilliantly acted in the lead role(s) by James McEvoy.

Unbreakable is a deeply moving film about how David Dunn (Bruce Willis)—once a brilliant college athlete who has been emasculated by his wife, an overprotective physical therapist—discovers that he is not an ordinary man. David Dunn is actually a superhero, and Unbreakable is his origin story.

The famed Shyamalan “twist” is that the film’s art-film pacing, frequent low-angle shots, and glossy, sensuous images of the ordinary have lulled us into thinking that Unbreakable is set in the world that we all live in, the world where the extraordinary is impossible.

Split is a deeply distasteful film about Kevin Wendell Crumb, a psychopath with 23 or 24 personalities, who kidnaps three teenage girls and eats two of them. Split is disturbingly close to being a just a slasher flick, and it was enormously popular with precisely that audience.

I was delighted to learn that David Dunn and his arch-nemesis Mr. Glass (Samuel L. Jackson) would be returning in Glass. I was not thrilled that James McEvoy’s Kevin Wendell Crum et al. would be back as well.

And that, frankly, is the primary flaw of Glass. David Dunn and Mr. Glass should be the central characters. They have spiritual depth, tragic grandeur, and unfinished business. But the movie is hogged by McEvoy’s giddy cycling through his various personalities, chewing up the scenery and some of the extras in the process. Seriously, Mr. Glass didn’t even utter a word until half way through the movie.

Now, I am fully aware that Split partisans will disagree with me. But they probably find the movie unsatisfying as well, with David Dunn and Mr. Glass hogging McEvoy’s spotlight from time to time.

The bottom line is this: Glass is not a great movie, because the plot tries to synthesize too many elements and fails to do so in a satisfying way. Imagine a movie that tries to be a sequel to 2001 and A Clockwork Orange at the same time. Not even Kubrick could have made that work.

But is Glass at least good—good enough to see in the theater? Yes, emphatically yes. For in the end, Glass has a very important message. I won’t spoil the plot, so I will only mention things that are apparent in the trailer and other advertising.

Mr. Glass, David Dunn, and Kevin Crumb all end up in an institution for the criminally insane. Yes, Dunn has saved countless lives over the years, but he’s a criminal, because he took the law into his own hands. The police frown upon that. They’d rather have dead citizens than vigilantes running around.

In the institution, the trio are placed under the care of Dr. Ellie Staple (Sarah Paulson), who specializes in treating patients with delusions of grandeur. Her goal is to talk Mr. Glass out of thinking he’s a supervillain, David Dunn out of thinking he’s a superhero, and Kevin Crumb out of thinking he’s a bit of both, perhaps. She tries to persuade them of mundane, materialistic explanations for what seems to set them apart from the rest of humanity.

But Mr. Glass is a mastermind, and masterminds are always a few steps ahead. And suffice it to say, Dr. Staple does not talk him out of his “delusions.”

I am not going to stay any more about the plot. But the takeaway message of Glass seems to be that Dr. Staple’s brand of psychological materialism is nothing but an ideology of social control. And just as in Unbreakable, Mr. Glass reasons that if there is a person like him in the universe (a supervillain with brittle bones), there is his opposite (an indestructible superhero), if there is a group of people dedicated to attaining superhuman excellence, for good or evil, then there must also be a group of people dedicated to crushing superhuman excellence to maintain control of a flat and mediocre world.

Glass is a battle between the Superman and the Last Man, and Shyamalan is clearly a partisan of human excellence against the leveling forces of modern liberal democratic society. That makes Shyamalan in essence a man of the Right. Thus it should come as no surprise that Glass has received overwhelmingly negative reviews in the mainstream media. People on the Dissident Right, however, are better equipped to appreciate it. Thus I give Glass a qualified recommendation. Glass fails to be a great movie. It is sometimes deeply frustrating and distasteful. But it nevertheless deserves praise for offering a defense of human greatness from modern egalitarian mediocrity. I found the ending genuinely moving. Glass is a noble flawed film.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

2 comments

I saw GLASS about 6 weeks ago. Aside from the fact that Shyamalan is a sub-continental (thus, why is he in America? who let him in?), one little scene in GLASS stuck with me, and totally discredits this far-reaching notion that he is a man of the Right. Indeed, it shows him to be a man of the hardcore PC/antiwhite Left.

Early in the picture, hero Dunn/Willis exercises some vigilante justice on a pair of miscreants who had just finished playing and filming the “knockout game”. One thug had viciously knocked down an Asian man walking on a sidewalk; the other filmed the crime, and later uploaded the footage to the internet. The “twist”? Both of the thugs are … WHITE!

Has there been a single recorded instance of Whites playing the “knockout game” (which should of course be treated as attempted murder, as well as – in these juridically degenerate times – a “hate crime”)? Of any racial group other than BLACKS engaging in this despicable behavior?

So pray tell why this “director of the Right” indulged in this cinematic unrealism?

Good point. I had forgotten about that incident. Tell me, though, in the context of the larger message of the movie how much it really matters?

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.