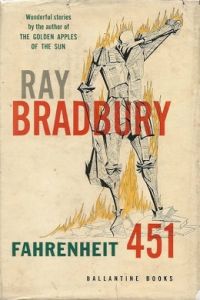

Ray Bradbury’s classic dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 was first published 68 years ago, and the first film adaptation was produced in 1966, but its messages remain surprisingly relevant today. Although many interpreted it as merely a story about government censorship, Bradbury himself characterized the work as a statement on the dumbing-down effect of television. Rather than government-imposed censorship against the will of the people, book-burning is welcomed by a complacent population who resent anything beyond the mundane.

The film adaptation from French director François Roland Truffaut stars Austrian actor Oskar Werner, who may have been chosen due to his own life having several parallels to his character Guy Montag. Montag is a fireman who burns books for a tyrannical and philistine regime. Eventually, he comes to realize the value of literature and is forced to abandon his position and flee the city, joining a group of like-minded people in a rural area. The real-world Werner was drafted into the German military during the Nazi era, and like Montag, was uncomfortable with his role due to moral convictions. As a pacifist and an opponent of National Socialism, he eventually deserted and went into hiding in the woods around Vienna.

Both Montag’s conformist wife Linda and his young dissident friend Clarisse are played by the same actress, Julie Christie. As with Montag and his change of heart regarding his career, this is presumably a statement that rather than conformists and dissidents being entirely separate groups of people, the same person can be both at different times. This is reflected in the contemporary Dissident Right, with most people having been more mainstream in their thinking at some point in the past.

The film describes the attitudes underlying censorship efforts in the present day very well. The captain of Montag’s fire brigade explains that books make people unhappy, as readers may dream of being someone they are not. Far from having an ethic of self-improvement, he condemns such aspirations as vain, pointless, and even insulting to others. People who read books must think they are better than their neighbors, he insists, which will not do. This reflects the same sort of jealous leveling attitude which was a major theme in communism and persists in modern-day social justice thinking.

Another major factor is the desire for a quiet, routine life, undisturbed by anything out of the ordinary. At one point, Montag forces Linda and her friends to listen to his reading of an excerpt from David Copperfield expressing the experience of a man in an unhappy marriage whose wife falls ill. They object to the book on first sight of it, and as he reads, one woman named Doris begins to cry, explaining that she “can’t bear to know those feelings. I’d forgotten all about those things.” Rather than appreciating that life naturally includes negative emotions, one of Linda’s friends calls the material “sick” and reading it cruel. Another denounces the “evil words that hurt people.” Linda reproaches Montag for making Doris cry, and is unmoved by his explanation that “she cried because it is true.” This sort of shallow philistine attitude is apparent throughout the film and common in contemporary society; we are all familiar with activists who believe that some speech should be banned because it can cause certain emotional reactions.

A common characterization of primitive or degenerate people today is that they have no future and no past, but live only in the immediate present. The population in the film naturally has little historical memory, being cut off from literary and historical documents by the taboo against reading and their own lack of curiosity. But they also lack much memory of their own lives. At one point Montag asks Linda if she remembers the day they first met, and she cannot. He finds this sad, but she cannot even see the value of such a thing. The closest she comes to concern for the future is hoping that if Montag gets a promotion they can afford a second viewscreen.

You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here.

As is the case today, the amusements of the masses include drugs to alter their mood, and many do not care about the risk involved. Montag comes home one day to find his wife unconscious on the floor, having taken numerous pills. He calls an ambulance, but both the man answering the phone and the men who arrive at his house seem much less concerned by the situation than he is. The paramedics assure him that they handle 50 such cases a day and that she does not need to see a doctor. Instead, she is treated on the scene with a blood transfusion, and although she is still unconscious, a paramedic assures Montag that she will be feeling perfectly well in the morning. He is telling the truth, but the men’s nonchalant attitude is still unsettling and points to an irresponsible society.

The next day at breakfast, Montag starts to tell Linda about the incident, but stops himself as her attitude becomes clear. “Talk all you like, if it makes you happy,” she says, making clear that she does not see the value of telling or learning the truth, but sees speaking as only another form of pleasure. Montag realizes that she would not appreciate the truth; she is only interested in immediate pleasures such as taking pills and eating breakfast.

One of the strongest influences on most people is a simple desire to fit in, which takes precedence over the truth when the two conflict. In the film, television is an interactive experience, with the presenters sometimes pausing and addressing audience members by name to ask for their input. Linda is overjoyed at this experience, and upset when Montag points out that the presenters do not know her personally and are most likely using the name “Linda” to refer to thousands of viewers who share the same name. Even it is true, this is a mean thing to say, she complains. Obviously, it disturbs her feeling of belonging to a select group of viewers, which she values more than the truth.

This desire to fit in results in a tendency to follow the herd by believing whatever the established authorities say, and in this case the authorities speak largely through television. The “viewscreens,” as they are called, are a source of overt propaganda, telling the population how to think and how to live. There is a preview of modern social justice hypocrisy in a television presenter’s authoritarian admonition to “Smother malice, strangle violence, suppress prejudice, hate hate! Be tolerant today!” She also denounces those who read and encourages viewers to turn them in.

People in the film have only shallow emotional connections with each other, in line with a trend in the late 20th and early 21st century towards fewer meaningful personal connections. A 2006 study found that between 1985 and 2004, the mean number of people Americans said they could discuss important matters with dropped from 3 to 2. The number of people reporting no such confidants nearly tripled. A full 80 percent of respondents said they now discuss important issues only with family members, up from 57 percent 20 years before. [1]

In Fahrenheit 451, even family connections are not particularly strong. Montag points out to one of Linda’s friends that she does not even know where her husband is. She was told he was called away for military reserve training exercises, but he is out of contact with her and may well have been drafted into a war, where his life could be at risk. Another woman dismisses this concern, explaining that “it’s only other women’s husbands who get killed” in wars. A third agrees and adds that she has known people to die in other ways, such as “getting run over, jumping out of a window. . . like Gloria’s husband a few nights ago,” but seems quite unperturbed by this, explaining that “that’s life, isn’t it?”

Given a conformist society with little regard for personal ties or any values beyond immediate comfort, the demonization and shunning of dissidents are to be expected, in the film as in the current year. Anyone who breaks the rules will inspire scorn and there is little to restrain others from casting them aside. When Clarisse is fired from her job as a school teacher, she is given no reason. She assumes that it is because she has more creativity than most and makes her students think, similarly to another teacher whom she had replaced. Montag encourages her to return to the school and confront the authorities to demand an explanation. When she arrives there, she recognizes and greets one of her former students, who sees her, hesitates, and runs away in fear. A second boy has a similar reaction. Presumably, the students have already been made to forget that she was their teacher and believe that she is a dangerous subversive. She never gets to the point of facing the authorities, being overwhelmed by the way her students have already been alienated from her.

It is a long-standing pattern for those in the contemporary dissident right to be not only banned from social media platforms or other services, but to be refused any meaningful explanation for such a move. Whether this is an attempt to avoid liability for potentially illegal discrimination is unclear. But regardless of the motive, it gives the impression that certain people, based on their political beliefs, fall outside of the normal rules of human interaction. It is a cultish practice that belongs only in a totalitarian society like that of Fahrenheit 451.

It should also come as no surprise that such citizens will gladly inform on each other. In the film, there are public drop boxes where anyone can submit incriminating information on others, and Montag’s wife ultimately visits one of these to betray him to the authorities. When he is forced to flee the city, a car drives down the street with a loudspeaker commanding the people to help search for the fugitive, and every citizen dutifully steps onto their front porch to watch for him.

Science fiction is sometimes a fanciful imagining of the future, but it has also often been used to reflect current social trends. Literal book-burning is not yet a reality, but all of the attitudes underlying it in Fahrenheit 451 are very real. Efforts to censor ideas and punish those who express them are no fantasy either. If we are to escape this dystopian horror we will need a cultural shift to reverse the trend toward a shallow, rootless life.

* * *

On Monday, April 12th, Counter-Currents will be extending special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

As an incentive to act now, everyone who joins the paywall between now and Monday, April 12th will receive a free paperback copy of Greg Johnson’s next book, The Year America Died.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Notes

[1] McPherson et al, “Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks over Two Decades,” American Sociological Review, vol. 71, no. 3, 353-375, 2006.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Przedmowa

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Pour Dieu et le Roi!

-

Civil War

-

Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 1

-

National Socialism as a Magical Movement: Stephen E. Flowers’ The Occult in National Socialism

10 comments

451 was always my favorite of the Authoritarian Trinity, and it’s no accident that it was the first to be broadly removed from school curricula.

Instead of mainly portraying a populace browbeaten and manipulated by the external forces of the state, it showcases the degenerate depravity necessary for such a state to exist and operate in the first place. I do not recall the text making more than a minimal effort to absolve the uncritical and hedonistic masses of responsibility for their own condition, and the main character undergoes an arc of redemption to explicitly address this.

1984 and the like contain what I consider to be less pointed narratives of individual helplessness and non-specific caricatures of state power. These are paradoxically quite useful to ZOG. The deeper messages in that particular work are easily missed, leaving only a superficial distaste for authority which is easily associated with “those bad Nazis” and channeled into anti-social behaviors like libertarianism and anarchism.

One book that gets overlooked in this genre if you will is We by Yevgeny Zamyatin. Check it out.

It doesn’t depict an ‘authoritarian’ dystopia, but The Time Machine, the sci-fi novella by H. G. Wells, is a first-rate read and seems even more relevant today as it touches on eugenic themes (or rather dysgenic themes).

And the 1960 film, starring Rod Taylor, has worn well and has a cool model of the time machine.

I love the book but the movie totally falls short. I bought it several years ago and I TRIED to like it, but it pales in comparison to the book. Just the omission of the fire dog alone was enough for me to dismiss it.

I read the book when it was still assigned reading in school (1970s). I honestly don’t recall most of the dialogue examples given in the post, but it strikes me how en pointe it is regarding women and the emphasis on being ‘nice’ rather than honest or truthful. Feelings trump all, etc.

It is also worth noting that, back when this book was used to teach, we were taught the evil of book burning and censorship. But we were never taught precisely what the evil notsees actually burned and censored. It was only after joining the DR that I learned about Hirschfield’s institute and a lot of the subversive literature that the authorities burned in Germany. And even back in the ’70s as a child of liberal parents, I thought their denunciation of ‘modern art’ was absolutely correct

” . . . certain people, based on their political beliefs, fall outside of the normal rules of human interaction. It is a cultish practice that belongs only in a totalitarian society . . .”

This post has arrived at almost the same time that I had been thinking about this book — which I had read years ago — in reference to the banning of books on Amazon, and the deplatforming of numerous websites and the closing of Twitter accounts, including that of the President of the United States! Good grief, no matter whether you agreed with him or not! It all adds up to exactly what “Fahrenheit 451” spoke of 50+ years ago.

At the time of publication, which I’m old enough to remember, people opined, that this could never happen ‘now’ or happen ‘here’ in the United States. They said it could only happen in the Soviet Union under communist dictatorship or that it had only been possible under the now-totally-defeated Nazi insanity.

Well, here it is, complete with the all-encompassing 50-inch TV screens to distract our minds, and the vast shopping malls to complete the process.

And as for the number of people with whom I can discuss important ideas and concepts — which includes White Nationalism, God forbid!, or just plain-vanilla capitalism and social problems — has dropped to zero in my former circle of friends. One friend of 40 years refused to ever speak to me after I voted for Trump. And I’ve outlived my small family, though I’m sure my aunt and uncle would ha been horrified by the regimes of Obama and Biden.

As an aside, I have been saving books on European History and Culture for years, an archive of sorts, that I’ve ‘rescued’ from charity shops and library ‘donation sales shelves’. In the past three years, I have added ‘banned books’ to my collecting of books headed to the ‘bonfire’, which are being thrown out from libraries, public and K-12 school and collegiate stacks. I urge everyone here to do the same — it’s obvious they’re soon for the trash heap, which takes the form today of an out-of-sight shredder rather than the bonfire.

Really an excellent, timely essay.

Ray Bradbury may have been a jew, he alluded to the jewishness of a lot of his characters in his short stories.

What are you talking about?

Bradbury was part Swedish, part English. One of his forbears had been involved in the Salem Witch Trials. Whatever he was or wasn’t, he wasn’t Jewish.

Great review.

I must audiobook this soon.

Is the HBO version worth a look?

So true about cancel culture and social justice terrorists. A professional writers guild of which I was a paid member in good standing for four years recently expelled me via secret meeting and secret vote. They found my written statements of truth (China Virus etc) and unabashed support for President Trump to be too much to bear and they drummed me out like the anonymous leftist cowards they are. Not one among them was willing to face me like a man and deal with as such. Groups like this are filled with communist sympathizing beta males, angry women really. But with dicks instead of cunts.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment