Berkshire County in Massachusetts consists of the westernmost nine percent of the state that played such an illustrious role in the founding of our nation. Today, that county illustrates the irony confounding much of our nation: that we hear the loudest yelps for diversity among those who live in almost entirely white areas.

As of the 2010 census, Berkshire County was still over ninety-two percent white, yet in 2016 it voted for Clinton at a ratio greater than five-to-two. In fairness to my fellow Northeasterners, two counties adjacent to Berkshire County – Litchfield in Connecticut and Rensselaer in New York – went for Trump, while all other adjacent counties – Columbia in New York, Bennington in Vermont, and Hampden, Hampshire, and Franklin in Massachusetts – at least posted more favorable numbers for Trump (though the last two listed just barely).

Yet despite this singular political masochism of Berkshire County, it still cannot avoid showing its European heart. Especially during the summer, a sojourn there offers abundant cultural produce. Allow me to whet your appetite with a report about my feast last week, which began at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, continued with a performance of As You Like It by Shakespeare and Co. in Lenox, and concluded with a stirring concert of piano quartets by Mahler, Mozart, and Brahms, two miles down the road in Lenox, at Tanglewood.

***

In the early afternoon on August 17, without any idea of this summer’s specific offerings at the Norman Rockwell Museum, I arrived to find the majority of the gallery space devoted to an exhibition that could only thrill awakened white Americans. Titled Keepers of the Flame: Parrish, Wyeth, Rockwell and the Narrative Tradition, the exhibition consists of a plethora of paintings by Maxfield Parrish, N. C. Wyeth, and the museum’s namesake, as well as a healthy number of works by other painters – American and French – who were teachers to those three (or teachers to their teachers).

As the title indicates, the primary underlying theme is the great chain of teacher-student relationships in the history of Western painting, and the passing down of traditions from one generation to the next. The exhibit includes a huge touch screen, which displays a tree of such relationships, connecting Parrish, Wyeth, and Rockwell all the way back to the fifteenth century. (One finds that this tree includes that all-time genius, Leonardo da Vinci, among other historic figures.) The “narrative tradition” in the subtitle refers to the idea that keeping the flame is as much or more about passing down cultural and mythological traditions as technical or scientific ones. There’s also a more limited aptness to narration in that Parrish, Wyeth, and Rockwell did much commercial work, including illustrations for narrative texts.

Even aside from any taint of commercialism, undoubtedly some – pretentious and down-to-earth alike – would find Parrish and Wyeth (but particularly Parrish) to also have those qualities for which many critics often dismiss Norman Rockwell: sentimentalism, mass appeal, a disregard for the contemporary Zeitgeist of fine art, and so on. But I imagine that pace any such impressions of these artists, most viewers would find this exhibition to be at least a breath of fresh air from the Abstract Expressionism which so dominated the history of twentieth-century American painting – that spiritually castrated genre of the random splatters of Jackson Pollack, the stupid rectangles of Mark Rothko, and the utter nihilism of Ad Reinhardt.

In any case, a number of the paintings on display this summer in Stockbridge complicate dismissive generalizations of Rockwell and company. For proof that Rockwell is not merely a Pollyannaish portrayer of mainstream Americana, see, for example, these two portraits of Russian girls, and the complex facial expressions rendered in rustic brushstrokes:

No one disputes that Rockwell was a skilled draftsman, but perhaps underrated are his intellect and range, both of which shine through in Stained Glass Window. In this piece – constituted primarily of symbolic imagery – Rockwell masterfully pulls off a nearly photorealistic effect in a meta-work of art:

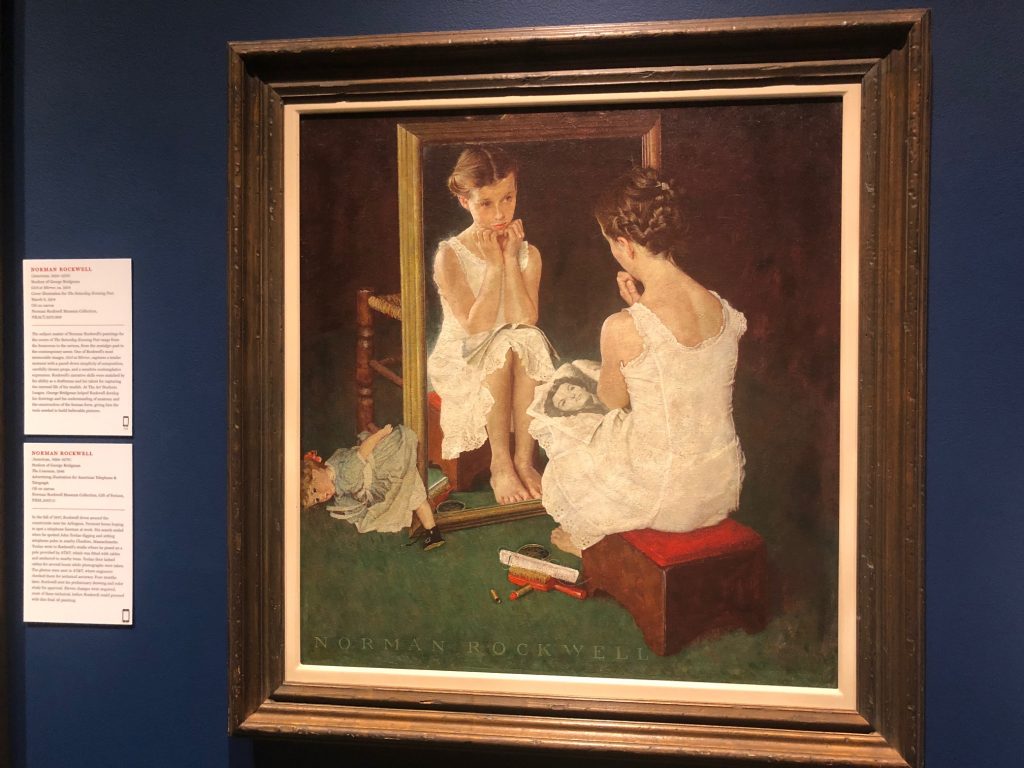

Even quintessential Rockwell can reveal depths of subtlety that cut against his reputation for corniness and cheesiness. Take, for example, one of Rockwell’s most famous works, Girl at Mirror, the image of which once featured on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post. The placard next to the painting in the exhibit refers to Rockwell having captured “a tender moment . . . and a sensitive contemplative expression.” I see, rather, a painting of subtle horror, wherein a young girl narcissistically tries to look like a pin-up model, as her neglected doll is bent over and sodomized by the mirror frame:

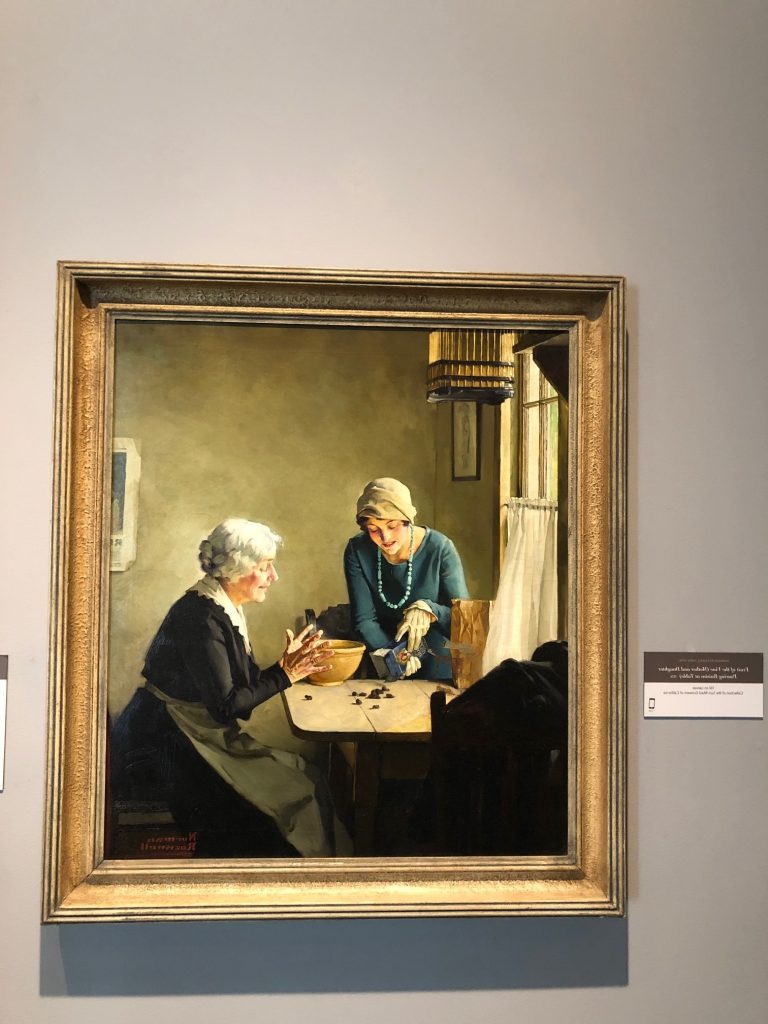

Not narrowly American, Rockwell’s art often recalls the European tradition generally, as it does explicitly in the following paint-child of Vermeer, Fruit of the Vine (Mother and Daughter Pouring Raisins at Table):

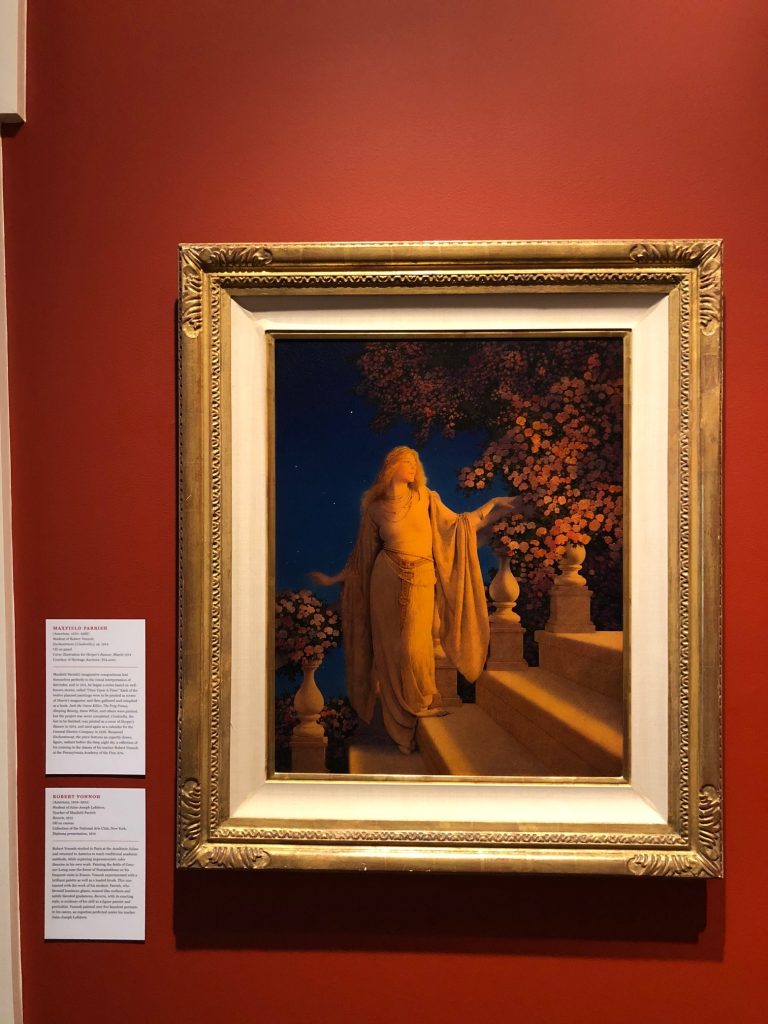

Of course, even as one appreciates Rockwell, one understands the critical view of much of his work. The same is true of Parrish, though if his work has too much sentimentalism, it is of quite a different character than Rockwell’s: luminous classical idealism rather than Main Street Americana. Perhaps in a less precarious time for Westerners, I’d consider Parrish cloying, but as it is, I find the brilliant glow of paintings like Enchantment (Cinderella) and The Lantern Bearers to be rather skillful, original, and even magical:

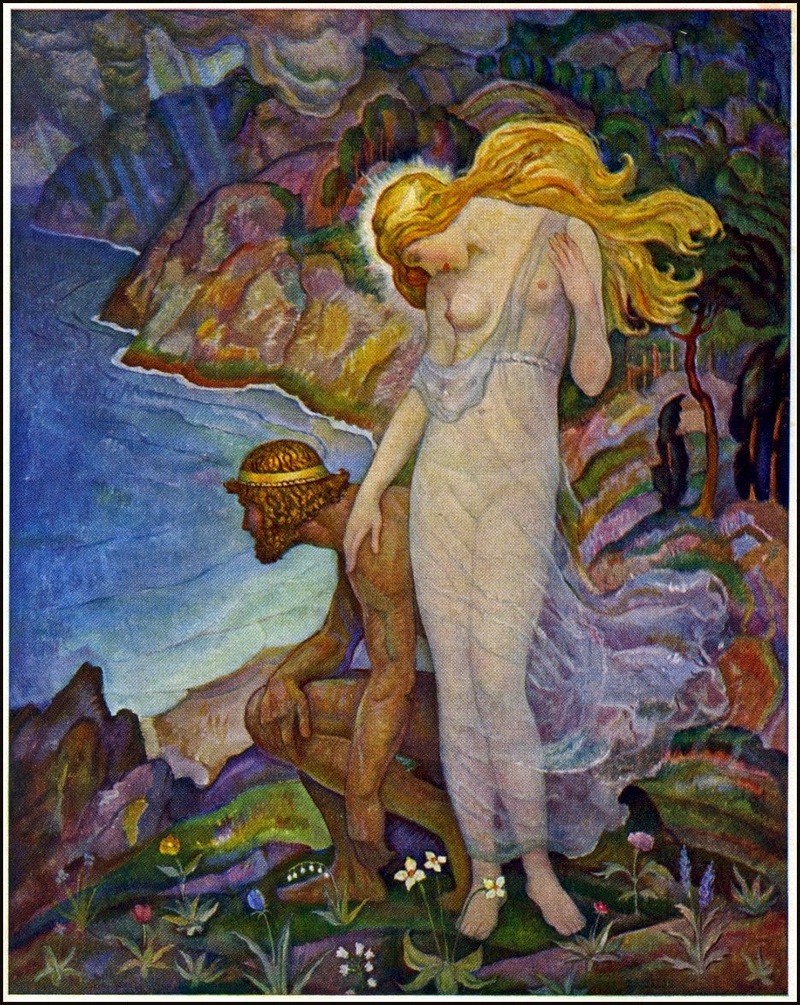

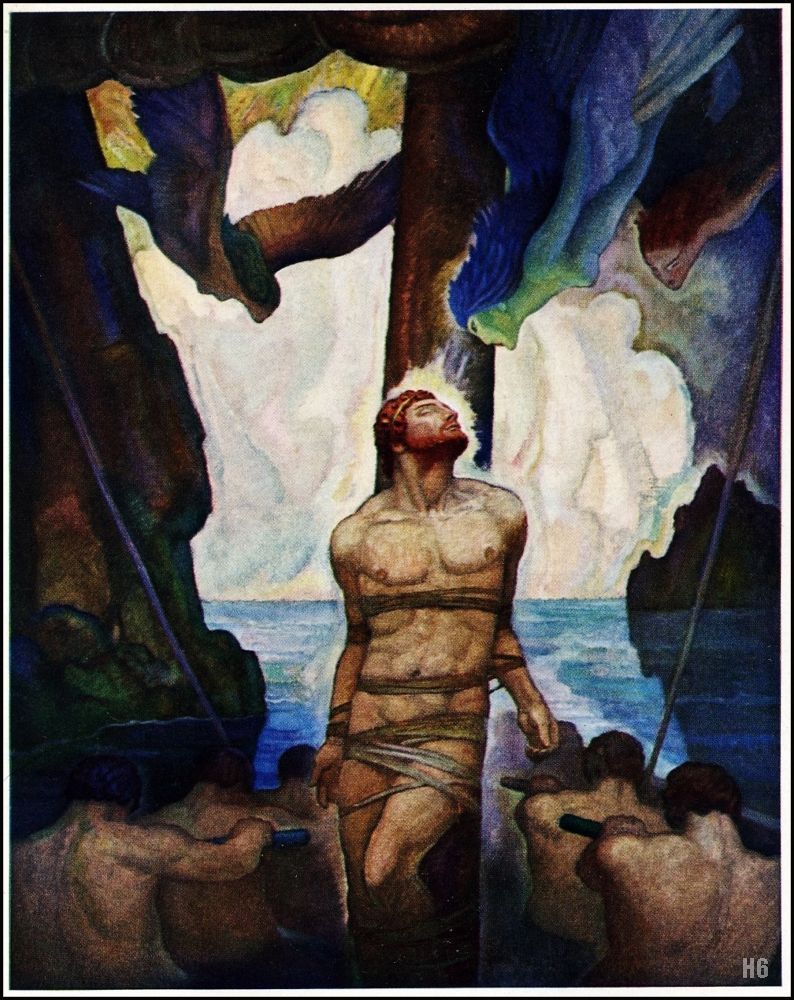

Judging by the exhibit, Parrish’s art – and Wyeth’s and Rockwell’s – was usually not in service of a tradition-destroying commercialism. It rather injected tradition into the realm of the commercial, as with Prometheus (the image of which was used in an advertisement for the Edison Mazda Lamp):

An example of N. C. Wyeth’s “traditional” commercialism (not on display at the exhibit) is this illustrated edition of The Odyssey:

In general, Wyeth’s oeuvre demonstrates the wide compass of the American tradition. The subjects of his paintings on display at Keepers of the Flame range from solitary American Indians, to white Americans exploring the Western frontier, to bucolic rural scenes squarely within the nineteenth-century French tradition. An example of the latter is The Scythers, which shows a deep resemblance in tone and texture to William Bouguereau’s By the Sea, one of the French paintings on display at the exhibit:

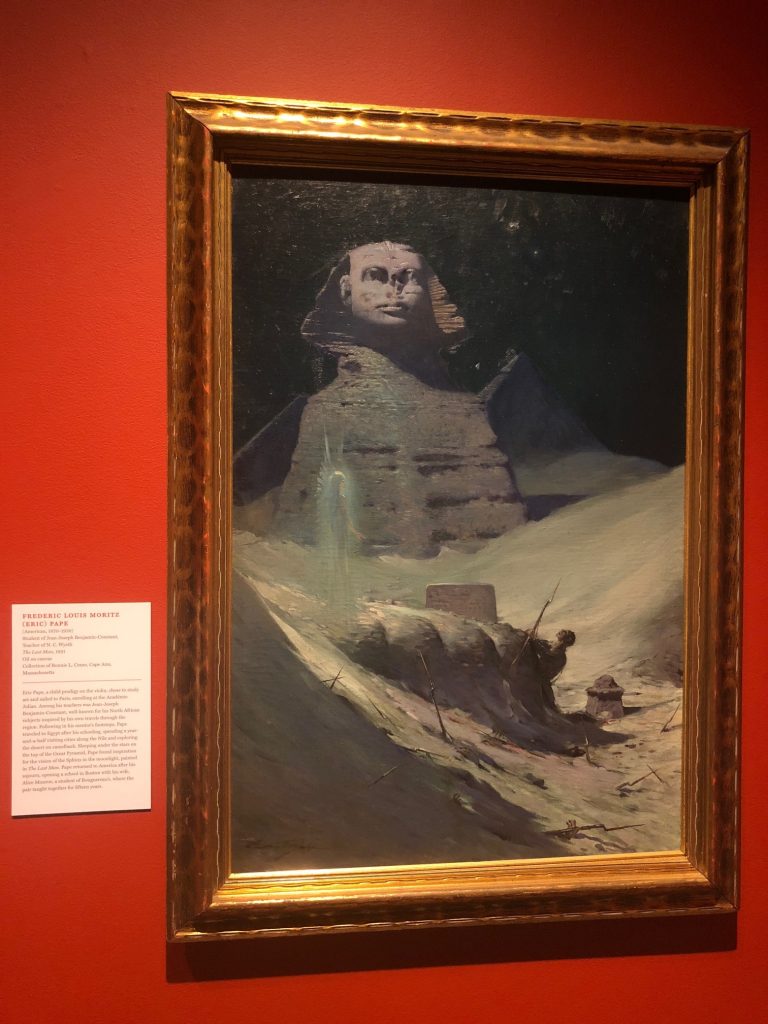

But Bouguereau was not teacher to Wyeth. He was, rather, grand-teacher to Parrish, through the American Thomas Anshutz. One of Wyeth’s teachers was the American Eric Pape, whose contribution to the exhibit includes the arresting The Last Man, which could easily be the cover art for a philosophical sci-fi novel:

In making art with broad appeal and for compensation, Rockwell, Parrish, and Wyeth were not “selling out” per se. Though it is crucial for art (and society at large) to maintain something of the aristocratic posture, this is often best accomplished through an effort to raise the consciousness of the masses closer to that of the aristocrat. It is a fair topic for debate whether the three painters at issue here accomplish this, but nearly all agree that Shakespeare’s art is of the noblest cast, and yet he has also been a most popular playwright, from his time down to ours.

***

Shakespeare charmingly encapsulated the necessity of appealing to an audience in the title of his comedy As You Like It. I attended an outdoor performance at the Shakespeare and Co. grounds in Lenox at five o’clock in the afternoon. The Sun gloriously bathed actors and audience alike in golden light as it gradually descended over the green Berkshire hills surrounding us. With the aid of sunglasses to soften the glare, it was the perfect setting for a Shakespearean comedy that takes place in the forest.

The play begins with Orlando, the youthful male hero, bemoaning the unjust treatment he receives at the hand of his older brother Oliver, the beneficiary of primogeniture. In Scene 2, we meet the cousins Rosalind and Celia, and learn that the former’s father, Duke Senior, has been exiled by the latter’s, the usurping younger brother Duke Frederick. The play therefore incorporates the Osiris-Set mythical theme, but in classic Shakespearean fashion, the Bard blends dualities, and we find both elder and younger sons constituting the male heroes.

By the end of Act I, despite (or perhaps implicitly because of) Celia’s lesbian love for her cousin, Frederick banishes Rosalind as well, and from here on out all the action takes place in the forest, where we meet a number of countrified characters in addition to the exiled aristocrats. Among the forest-dwellers is the mysterious, melancholy wanderer Jacques, who delivers one of Shakespeare’s most famous speeches midway through the play, on the seven acts and ages of man (which begins, “All the world’s a stage . . .”). This speech is one of those somber but wise interludes that Shakespeare peppers into his comedies – though it won’t spoil anything for those who haven’t seen or read the play to report that, as in Shakespeare’s other comedies, all ends well, with Rosalind and Orlando as the lead couple at the four-marriage finale.

Nine actors handled the entirety of the play, which calls for approximately twenty characters (though there are closer to a dozen or so well-defined roles). By and large, the nonet did a fine job, with one exception. Orlando was played by Deaon Griffin-Pressley, who is a dead ringer for Ta-Nehisi Coates, and this likeness was distracting, as was the lack of chemistry he had with Aimee Doherty (who otherwise did fine work as Rosalind). But even aside from this, Griffin-Pressley simply overacted, and did so in a narrow range of expression. Energetic and eager earnestness was the only note he struck.

Thankfully, in ensemble plays, it is hard for a single actor to ruin the whole show, and some of the other actors compensated. Mark Zeisler had just the sad eyes and wistful half-smile for Jacques, and he performed the traveler-philosopher well despite flubbing a few lines. Gregory Boover was charming as Silvius, a young shepherd we meet in the forest who is in love with the shepherdess Phoebe, and Mr. Boover also ably handled acoustic guitar duties for the silly-cutesy song-ditties that Shakespeare weaves into the play. (The first of those ditties begins, “Under the greenwood tree,” which Thomas Hardy used as the title for one of his classic novels.) MaConnia Chesser, a portly, middle-aged black woman, was entertaining as a female version of Touchstone, the fool who is actually wiser than most of the other characters, as Shakespearean fools are wont to be.

Since it is fun (and often useful) to commit to memory some of the brief witticisms from a Shakespeare play, I offer the following selection from As You Like It, along with fitting contexts for their use:

- for an atheist, when someone swears to God: “if you swear by that that is not, you are not forsworn”

- when falsely accused: “your mistrust cannot make me a traitor”

- when caught in a lie: “the truest poetry is the most feigning”

- for an attractive person caught in a lie: “honesty coupled to beauty is to have honey a sauce to sugar”

- when disagreeing because circumstances have changed: “‘Was’ is not ‘is’”

- when accused of not having done something that you may yet do: “omittance is no quittance”

Zooming back out, one of the principal themes of the play is the superiority of the rustic life of the forest compared with the pomposity of society. When we first meet Duke Senior at the outset of Act II, he asks rhetorically:

Are not these woods

More free from peril than the envious court?

Here feel we not the penalty of Adam.

Later, Corin, one of the simple shepherds we meet in the forest, explains the nature of his life:

Sir, I am a true labourer: I earn that I eat, get that I wear, owe no man hate, envy no man’s happiness, glad of other men’s good, content with my harm, and the greatest of my pride is to see my ewes graze and my lambs suck.

It is this simple, wholesome life that inspires Duke Senior at the end of the play, after all titles and riches have been restored, to delay returning to his court in order to rejoice in the forest. He encourages the marriage party to “forget this new-fall’n dignity / And fall into our rustic revelry. Play, music!”

***

Though “rustic revelry” does not usually best describe minor key piano quartets, I did my best to heed the Duke’s command, and proceeded to Tanglewood for some music, which is, like the Rockwell Museum and Shakespeare and Co.’s grounds, surrounded by hilly forest (see top photo).

The program included the first piano quartets of Mozart and Brahms – both in G minor – as well as the only surviving movement of an early Mahler attempt at such a quartet. The evening’s performers were the four women of The Skride Quartet, named after two beautiful Latvian sisters, the elder on violin and the younger on piano. Earlier this year, at The New York Philharmonic, Baiba Skride brought me to tears with her performance of Tchaikovsky’s stirring Violin Concerto, so I was quite excited as she and her fellow musicians walked onstage to a packed house and robust applause. Two hours later, they walked offstage to even greater applause, having more than satiated the audience with passionate, minor-key intensity.

The concert began with Mahler, which many readers will know from the Martin Scorsese film Shutter Island, in which it is explicitly discussed by the characters played by Leonardo DiCaprio and Mark Ruffalo. DiCaprio’s character, trying to place the familiar music in his memory, asks if it’s Brahms. While such confusion would be unlikely with regard to Mahler’s symphonies, the quartet movement was written early in Mahler’s career, before he assumed the bloated style of his symphonies. The piece is therefore indeed quite Brahmsian: passionate and romantic, without too much gesturing towards the twentieth-century trends of modernism that Mahler helped usher in.

The Skride Quartet immediately demonstrated its tasteful skill. A tricky thing with piano quartets is to make sure that the piano does not dominate too much, which is a risk even in a piano quintet. But during the Mahler piece, Lauma Skride, a year younger than her sister, masterfully handled her instrument, articulating her parts clearly without ever drowning out the strings.

As for Mozart, when world-class musicians are playing his music, one simply sits back and takes it in, grateful to be alive. I did so as The Skride Quartet graced the audience’s ears with the prodigy’s heavenly patterns, and as I was not much familiar with this piece beforehand, I did not have preconceptions as to how it should be played. I will add one comment, however, on Mozart generally.

Recently, a friend who does not listen much to classical music, and who is not at all musical himself, attended a concert of Mozart and Bruckner. He reported that he was quite intrigued by Bruckner, but found Mozart boring and predictable. Though I couldn’t feel any more different about Wolfgang Amadeus myself, I do understand what my friend means. For a number of reasons, the more formal classical music of pre-Beethoven times can seem to run together and blend into a predictable sound. One major reason, of course, is that since almost all music in the West is built upon the melodic and harmonic foundations laid down by the likes of Bach, Haydn, and Mozart, we take their originality and charm for granted as we do the air we breathe. But just as attending closely to one’s breath can thrill with the intensity of life itself, so does attending closely to Mozart and other composers from the more formal eras of classical music. If you find Mozart predictable, try intently focusing on some of his pieces in recordings, even pausing them at times to see if you can really predict what is coming. With such careful attention, you will find him surprising you at every turn, bursting with ideas of musical genius that enliven with the freshness of a deep breath.

Listening to Brahms is more like having a good cry – sometimes joyous, sometimes heartbreaking, often both at the same time – and the Hamburger’s Piano Quartet No. 1 is emblematic of his legendary passion. The Skride Quartet was up to the task in channeling that passion, and once again, the younger Skride perfectly handled the dynamics of the piano. A stunning instance was the martial-march theme that the piano announces a few minutes into the Andante con moto: it requires a firm and confident tempo, but a light touch on the keys, and Lauma nailed the balance. (For those less acquainted with Brahms, I recommend listening to this movement, which is in the heroic key of E-flat, for a taste of the quintessence of his music.)

It was the Brahms piece that brought the house down in thunderous applause, forcing the women back on stage three times for extra bows. The audience did not get its desired encore, but perhaps this was for the best, as one does not want to risk ruining the perfect capstone to an evening of excellent music. I highly recommend trying to catch such an evening when The Skride Quartet is on tour this coming season. As for Keepers of the Flame and As You Like It, they run through late October and early September, respectively, should you be in the area over the coming weeks.

***

That’s plenty of words for now on a single day, though it still just scratches the surface of what it is like to experience such an array of culture on a beautiful summer day in the rolling hills of western New England. My intention, dear readers, is of course not to gloat, but to provide a reminder of how rich our heritage is. I also wanted to highlight that even in places where our people are politically asleep, their hearts still beat European-American blood. There is yet much life left in our people, and despite our losses, we still have so much to fight for. Therefore, take heart, brothers and sisters, and if you need some help doing so, you can always turn to Shakespeare, Mozart, Brahms, and thousands of others of our dead, who’ve left us more treasures than can be savored in a hundred lifetimes.

Blue-State%20Arcadia%3A%20A%20Summer%E2%80%99s%20Eve%20in%20the%20Berkshires

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

The Terrible Loss of an American Patriot

-

Full Moon Madness: Is It Real?

-

Loving Lenny to Death: Maestro

-

Metapolitics in Germany, Part 1: An Exclusive Interview with Frank Kraemer of Stahlgewitter

-

The Bard Across Three Reichs: Germany, Shakespeare, and Andreas Höfele’s No Hamlets, Part II

-

The Bard Across Three Reichs: Germany, Shakespeare, and Andreas Höfele’s No Hamlets, Part I

-

Michigan’s Yankees

-

Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks: A Primary Text of Post-Colonial Jive Part 2

6 comments

Despite being landlocked, the region has a claim to sea story fame: Melville wrote Moby Dick on his farm on the southern edge of Pittsfield. From his writing desk he had a view of the back side of Mount Greylock, the only Berkshire that really qualifies as a mountain. He wrote that it looked like the back of a sperm whale. I visited that farm, Arrowhead, a few months ago and was crushed that fog and rain hid that view.

I spent a lot of time in the region, mostly the northern part, in the late 80s. I remember being in North Adams shortly after Sprague Electric closed. Sprague’s massive buildings now house large modern art pieces as part of MassMOCA, I believe. When Sprague closed I think that was it for that mill town, or was it? They still had a college in town, North Adams State. The story going around then was that North Adams had the highest percentage of teen pregnancies in the country. I doubted that then and I doubt it now, but even if it was true, so what? NA was 100% white. I never saw a black, mestizo, or Asian the years I was there. One time in 1986 I was on a bus (it was a real city, it had buses) and witnessed the local girl population. None looked pregnant, and they seemed sweet-natured, teenage plump (this was right before the obesity epidemic took hold), poodle haired, and gossiping about how cute Bon Jovi was. They were mostly French Canadians whose families had come to New England to work in mills for decades.

What’s my point? Not much except to remind that there were/are working class whites still around (I hope), even in exclusive arty areas where they’re not supposed to be.

Very nice review w/great pics.

While the Berkshires have a certain SWPL heritage — and don’t get me wrong: the area is beautiful; Tanglewood & Shakespeare & Co are top-notch & wonderful — the tonier areas (e.g., Lenox, Stockbridge; Great Barrington) have been largely overrun by snotty NYC Jews who use ‘summer’ as a verb. This trend has been happening for decades. (See Saul Bellow’s “Herzog” (1964) where the main character, who lives in Chicago, summers in the Berkshires). Economically depressed towns like North Adams are, for the most part, blown out opiate waste-lands ala the Rust Belt. Nationally, when people refer to “the Berkshires”, they mean Lenox, Stockbridge, and Great Barrington.

A few years ago, I spent some time in this northern part of Massachusetts. After attending a Tanglewood concert, my girlfriend and I stopped at a certain Lenox inn for a late night drink. Nearby in the dining room was an older Jewish couple from Philadelphia named the Goldbergs, who despite being from Philly must have originally been from NYC, given their stereotypical accents.

Mr. Goldberg struck up a conversation with a mixed-race gay couple next to them (a black man and a white attorney) on which dessert was better: the “To Die For Chocolate Cake” vs. the “Hazelnut Torte”. I considered slitting my wrists at that moment, but what I heard next left me gobsmacked.

As the Goldbergs were leaving the Inn, Mr. Goldberg struck up a conversation with the owner of the Inn, himself a Jew (“EG”). I could only pick up parts of their conversation, but contempt for the goyim was central to their conversation. At one point, EG says “80% of the visitors to Tanglewood are Jewish… and there’s a reason for that…” I missed some of the next sentence but did catch part of a followup sentence where EG said “One thing the goyim don’t understand… “. From this, I presumed he was talking about affinity for classical music. What was apparent in their mutual commiseration was the inference that goyim philistines don’t adequately appreciate classical music. Then Mr. Goldberg responds with: “I always say… they’re savages.”

That’s the Berkshires of today.

That conversation is typical of class climbers, rather than the upper class.

The tendency to (attempt to) punch down is ubiquitous with class climbers, who are generally seen as more vulgar than even the lower classes (hence the visible upper class hate for the middle class).

Punching down a psychological mechanism that attempts to self-sooth in their class perception, and differentiate themselves among people that they just might be mistaken for. They can’t have that, and so they need to articulate the difference. Its wholly lower class behavior (See Paul Fussel’s book: Class). Such behavior speaks more to why Jews have always had a hard time penetrating the upper class, rather than any strictly racial reason. They simply aren’t very far out of the ghetto, and their impulse to tear down White society is always there as it is for all outsiders (by definition: savages).

Thus, with Jews, this behavior also takes on a measure of projection, as they have long been the savage outsiders to White culture. They still are, in spite of this very temporary period of in-road into a relatively upper class status for some. And whether in the Berkshires or in the European environments that bred the music that they make pretensions toward appreciation of, they are swimming in the White Gentile cultural pool. Nothing will change that. They know this, and thus will continue with their culture wrecking while revering it at the same time.

Many of the smaller Yankee towns and cities in Massachysetts are overrun with Hispanics. Lynn, Lowell and Lawrence to name a few. I-495 separates Lawrence front North Andover I believe and as usual a highway separates the races with the city of Lawrence being a haven for MS-13. This is nothing but population replacement.

That is a good article, and very much appreciated the works you photographed, sure gives me a different perspective on Rockwell.

My only quibble is w.r.t. Hardy’s Under the Greenwood Tree.

Sure, it is outside the scope of your review/article, but if you mention it, it is more than a tale of bucolic peasant life. When reading it, the thing that really startled me was what Hardy depicts as the persistence of pagan customs in England long after the Industrial Revolution was well under way.

It is not a work of non-fiction, I know, but those aspects are clearly based on Hardy’s own experiences and observation. I am sympathethic with it, though Christian, as I am with the ancients.

I am old enough to have danced around a maypole before the custom was mainly abolished or made nonsecical.

Do not much like neo-paganism, mainly wiccans and occultists faking it (though I am greatly admiring Emperor Julian), but I strongly recommend Hardy’s Under the Greenwood Tree to any sympathetic reader of this site, I am sure many would greatly enjoy it, it is very quiet and very educational.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment