Christian Reconstructionism and Ethno-Religious Conflict, Part 1

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right2,633 words

Part 1 of 3 (Part 2 here [2])

The Christian Right [3], or Religious Right, was an enormous force in American politics until George W. Bush got them to support his war against Iraq [4] on behalf of Israel [5]. Because the Iraq War turned out to be a disaster, the Christian Right lost much of its support in broader American society. Between 2001 and 2008, for example, Christian symbols such as the ἸΧΘΥΣ were replaced by pride flags on the bumpers and back windows of cars.

One faction of the Religious Right which stood apart from the others and consequently didn’t suffer the full effects of following Bush off a cliff was Christian Reconstructionism, a movement established by Rousas John Rushdoony (1916-2001).

Rushdoony was a unique minister in every way. He was of Armenian immigrant stock, but rather than being a member of the Armenian Apostolic Church, he was a Protestant whose theology would have been recognized as their own [6] by the Puritans of Massachusetts [7]. Rushdoony was also a libertarian Christian who sought to base American society [8] on Biblical law [9]. He was also not a Christian Zionist [10].

While Rushdoony could have fit in as a Puritan minister [11] in seventeenth century New [12] England [13], his Armenian heritage was tremendously important to him personally. The story of the Armenians is one that is absolutely critical for old-stock [14] Americans [15] to know. Armenians are an Indo-European people [16] who live in eastern Anatolia and the Caucasus Mountains. According to the Anatolian Hypothesis [17], the homeland [18] of the proto-Indo-Europeans [19] is very close to the traditional homeland of the Armenians [20]. The Rushdoony family had roots in the Armenian city of Van [21] going back to the time of the Prophet [22] Isaiah [23].

Jesus of Nazareth’s ministry was mostly spread in Greek [24]. The first Christians were Hellenist Jews, and the faith spread quickly to the Greeks of Asia Minor. Christianity reached Armenia shortly thereafter. Two of Christ’s disciples, Bartholomew [25] and Thaddeus [26], evangelized Armenia, and King Tiridates III converted to Christianity in 301, making Armenia the first Christian kingdom. Armenia also served as a buffer state between the Roman and Persian empires [27].

The Ottoman Turks captured the city of Constantinople in 1453 and put an end to the Eastern Roman Empire, and Armenia subsequently became part of the Ottoman Empire as well. The Ottomans had a powerful army and an aggressive military [28] policy, but the Empire suffered from a number of structural flaws, and by the nineteenth century its decline was clear to all.

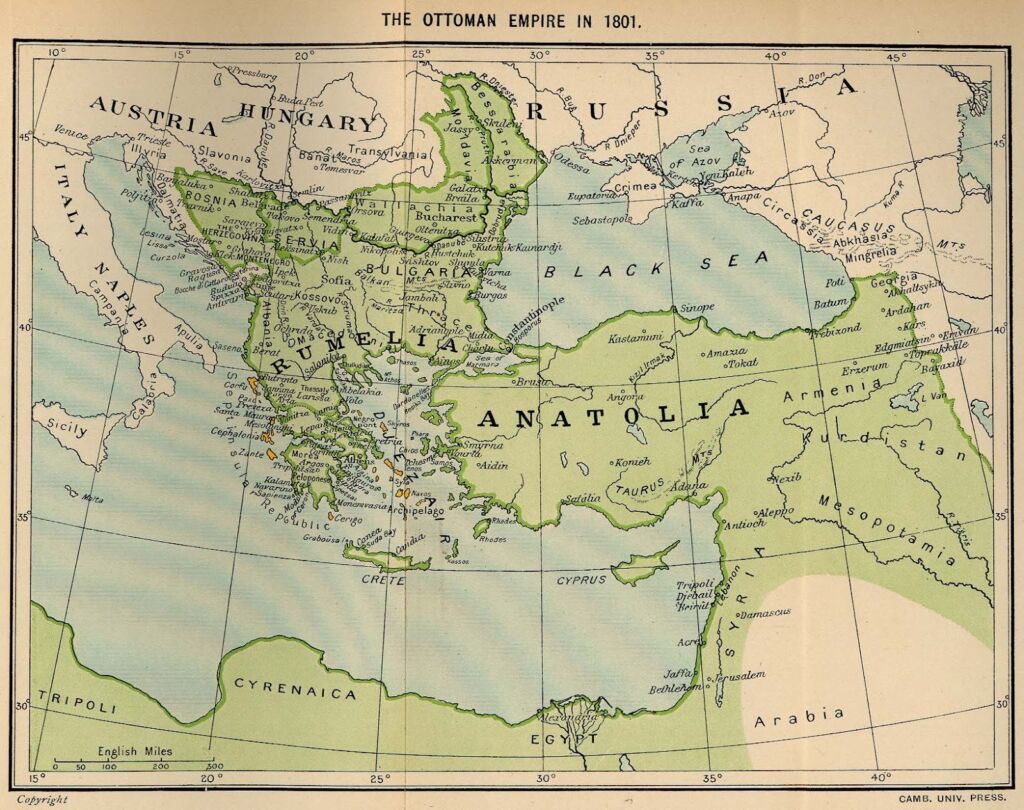

[29]

[29]The Ottoman Empire controlled the entire Balkan Peninsula by the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Christians in the Ottoman Empire and the Young Turks

Relations between Muslims and Christians in the Ottoman Empire were usually stable, but in the early nineteenth century Serbians [30] and Greeks, both Orthodox Christians, revolted. Greece became an independent kingdom in 1830, while Serbia became fully independent in 1833.

The Ottoman Turks responded to the loss of Greece by removing ethnic Greek Christians from top spots in government, often replacing them with Armenians. Newly-independent Greece also launched a cultural and metapolitical campaign aimed at influencing the Greeks in the Ottoman Empire, revitalizing the Greek language in Anatolia. The campaign recalled the glories of Athens [31], Sparta [32], and the Byzantine Empire. This led to an anti-Christian reaction by the Ottomans which grew in strength throughout the nineteenth century.

Protestant missionaries began to appear in the Ottoman Empire in the 1820s. They were allowed to operate as a part of deal the Ottomans struck with the British with the caveat that they could only proselytize among the Christians and Jews. Because of the efforts of Anglo-Christian missionaries, the number of Armenian Protestants increased from 1,300 in the 1860s to 50,000 in 1914. most of them in eastern Anatolia.

Armenia’s Protestant evangelization [33] took place alongside an Armenian national and cultural revival. Wealthy Armenians paid for Armenian youths to study in France and other places, and an Armenian National Assembly formed. But as this was happening, the Ottoman Empire continued to lose ground. The Russians advanced in the Caucasus as well as in the Balkans, and Romania won its independence following a revolt in 1859. Bulgaria revolted in 1876 and achieved independence a few years later. These events led to Muslim refugee streams which flowed from the newly-independent lands into the core of the Ottoman Empire. Additionally, semi-nomadic Muslim tribes such as the Kurds discovered that they could now emigrate into eastern Anatolia — the Armenian homeland.

Tensions over national and religious differences were on the edge of breaking out into violence throughout the Ottoman Empire by the late 1870s. In the Armenian regions, for example, it was clear that there was a two-tiered justice system [35]. Muslims, usually Kurds, would attack Armenians in various ways but were rarely punished. Rival warlords also fought over the right to collect taxes, including a special tax for Christians. Turkish judges berated Armenian witnesses in legal trials, and Turkish or Kurdish Muslims were rarely, if ever, convicted of any crime carried out against an Armenian.

The first massacres of Armenians on a large scale began in 1894. These massacres were not directed against Greek or Assyrian Christians, but only Armenians. The issue of whether or not the Sultan’s government organized the killings is still debated. It is entirely possible that the butchery was solely the result of government inaction and inefficiency, but the evidence leans towards government-organized murder. The various European diplomatic missions in Constantinople certainly believed the Sultan’s government was responsible. Additionally, many of the Kurds were suspiciously armed with expensive modern rifles. Soldiers and the police were also involved, and there was no indication that they were part of a rogue force acting contrary to Ottoman policies.

The British Ambassador, Philip Currie, met with the Sultan in January 1896 to complain about the massacres. Currie tactfully claimed that “[t]he religion of Mohammed was highly respected in England and that no one attributed the crimes that had been committed to its teachings.”

[36]

[36]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Against Imperialism here [37].

“This,” write Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi, “was hogwash. British diplomats, like most Western observers, understood that what had happened was closely bound up with the Islamic fervor [38] projected from the Porte [39] and embraced by many Turks.”[1] [40] By 1890 radical Islam had spread across the Ottoman Empire, manifesting in a visceral hatred of Christians.

The massacres led to a group of Armenian fighters capturing the Imperial Ottoman Bank on August 26, 1896. The fighters held the European businessmen who were in the bank hostage. They also fired at Ottoman soldiers and threw explosives out of the bank’s windows. The purpose of the raid was to raise awareness of the ongoing atrocity and to persuade Europeans to put a stop to the killing. There was however no European intervention, although the plight of the Armenians became widely noticed. European diplomats helped the Ottoman government to negotiate an end to the hostage crisis, and the surviving Armenian fighters were sent to France. The Ottoman authorities backed an attack on the Armenians in the hometown of the bank raid’s leaders, but shortly thereafter they sent clear orders calling for an end to the bloodshed. The bank raid was therefore a success.

One of the atrocities commonly committed by the Turks and Kurds against the Armenians was to cut out the eyes of Christian Armenian priests. One such unfortunate priest was Rousas J. Rushdoony’s grandfather. He therefore couldn’t read the liturgy, but memorized it so that he could continue his work. When the Muslims discovered that Rushdoony’s grandfather was able to carry on with his ministry, he was killed. Rushdoony’s grandmother and a sibling died shortly thereafter, and Rushdoony’s father, Yeghiazar Khachadour “Y. K.” Rushdoony, was orphaned at the age of 14.

Y. K. was found by Protestant missionaries while wandering the streets of Van and placed in their orphanage. When they discovered that Y. K. was bright, they began educating him. Y. K.’s extended family eventually discovered his whereabouts, but they decided to keep him at the missionary school so that he could get an education. Y. K. was later sponsored by British Presbyterians to attend the University of Edinburgh.

Meanwhile, the Ottoman Empire continued to bumble along. In 1908, a group of military officers and educated men called the Young Turks forced the Sultan to restore the 1876 Constitution. This was expected to put an end to ethnic tensions across the Empire. That summer, celebrations were held in honor of the expected emergence of Muslim-Christian unity on a large scale. Even the Patriarch of the Armenian Church, Madteos II Izmirlian, who had been cast out of Constantinople for protesting the Armenian massacres in the mid-1890s, was allowed to return from exile in Jerusalem.

[41]

[41]This 1908 postcard shows the various ethnic groups of the Ottoman Empire “United for the Fatherland” following the Young Turks’ revolution and the restoration of the 1876 Constitution.

Underneath the public celebrations, however, problems remained. The murders of the Armenians were still very fresh. Additionally, the Young Turks’ revolutionary movement was based on the French Revolution. While liberté, égalité, and fraternité look good on paper, all revolutions derived from the French model quickly come to blood [42]. The first inkling of ethnic trouble under the new political order came in November 1908, when Hüssein Cahid, the editor of the Young Turks’ newspaper, Tanin [43], wrote an article pointing out that if non-Muslim, non-Turks acquired authority in the Ottoman Empire — which was hypothetically possible under the new constitutional order — then it was possible that the new non-Turkish rulers would put the overall interests of the Ottoman Empire below their own narrow ethnic and national interests.

The revolution of the Young Turks appeared to be a model of progress at first, but it had upended the Empire’s social order. Autocracy keeps ethnic and national tensions down because it is impossible for any minority ethnic group to seize power. In a multi-ethnic democracy, however, demography is destiny, and every election becomes nothing more than a racial and ethnic headcount.

The first election following the restoration of the Constitution was held over the last two months of 1908, fraught with the danger of civil unrest. Hüssein Cahid feared that non-Muslims would adopt a sectarian approach to voting and that the Empire would become a Tower of Babel of inefficiency as a result. In Van, where Rusdoony’s family was living, the Armenian Dashnak Party [44] won on a platform of returning Armenian property that had been seized by the Muslims during the massacres of the 1890s. In the end, the Greeks and Armenians across the Empire felt underrepresented due to ordinary irregularities in voting, as well as way in which districts were gerrymandered to increase ethnic Turkish representation. The restored Ottoman Constitution thus rendered the various ethnic groups in the Empire mortal enemies.

Matters came to a head on April 14,1909 in Adana [45]. Muslim Circassians, Kurds, Turks, and others wrapped white bandages around their fezzes and came into the Armenian quarter on market day armed with swords, knives, and axes. The Armenians closed their shops and retreated to defensible buildings. The rioting lasted for days. Government troops moved in to attempt to restore order, but they ended up attacking the Armenians as well. The Adana massacre was a severe blow to the post-restoration constitutional order.

Then, in 1911 the Italians attacked Turkish-controlled Libya as part of an effort to reestablish an empire. The Italian military was equipped with airships and other advanced European weapons, and the Turks were defeated in a little more than a month. This attack inspired the Orthodox Christian nations of the Balkans to expel what remained of the Ottoman Empire in the region in 1912. The Balkan Christians were united in dislodging the Ottoman Turks, but had overlapping claims among themselves [47]. The resulting lingering instability led to the First World War when the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s heir apparent was killed in Sarajevo by a Serbian nationalist in 1914.

[48]

[48]After the Balkan War of 1912-1913, the Ottoman Empire lost almost all its remaining holdings in Europe. The losses led to the Ottoman political elite adopting a siege mentality.

The Armenian Genocide

The loss of Libya to the Italians and the Ottoman defeat in the Balkans radicalized the Young Turks, increasing their power. Islamization remained powerful underneath their multicultural façade, as well as the idea of Turkifying the empire. The Young Turks wished to culturally assimilate the Arabs and expel the Armenians. They also rejected the “high” Greek-oriented Byzantine cultural form in favor of the Turkish peasants of Anatolia. Their dream dream was to convert the old Empire, which consisted of Orthodox Greeks, Armenians, Assyrians, and Arabs, into a pan-Turkic Empire [49] which would unite the Ottoman Empire with the Turkic tribes in Asia.

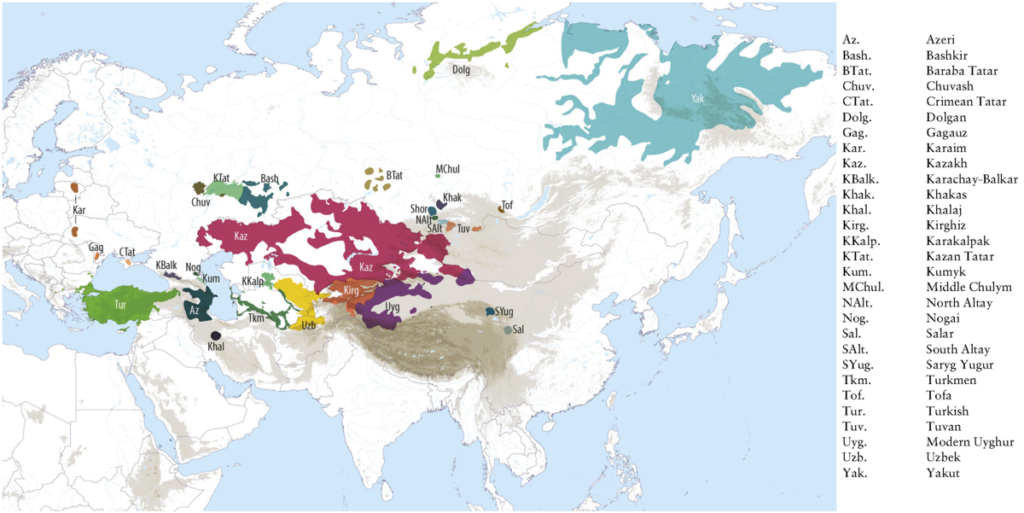

[50]

[50]The Turkish tribes are spread across Asia. Many Turkish intellectuals wanted to incorporate these tribes into the Ottoman Empire.

The genocide of the Armenians [51] was preceded by a campaign of deporting ethnic Greeks from Anatolia’s eastern coastal regions to Greece itself in 1914. This ethnic cleansing removed people whose ancestors had lived in the region for thousands of years. The genocide itself began after the Ottoman army was badly beaten by the Russians at Sarikamish, given that blame for the defeat was placed squarely on the Armenians.

First, the Turkish army shot the Armenian men who had been drafted into the labor battalions. The murdered Armenians were suspected of being subversives, and given the fact that so much blood had already been shed in the decade leading up to the First World War, the Turks were probably not wrong in their suspicions. The Turks had in fact guaranteed hostility from the Armenians though their actions. In Van, where Rushdoony’s family lived, the Armenians revolted when the Ottoman army attempted to draft Armenian men into the labor battalions.

[52]

[52]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Toward a New Nationalism here [53].

The Armenians of Van were able to successfully hold out against the Ottoman forces, and appealed to the Russians for support. Y. K. Rushdoony filed newspaper reports throughout the fighting for the English press. The Russian army reached Van on May 22, 1915 and lifted the siege. Rousas George, Rousas John Rushdoony’s older brother, died just before the Russians arrived.

The end of the siege did not bring the Rushdoonys any relief. There was no food to be found, and the Ottomans were maneuvering to recapture the area by mid-June. Any Armenians in the Turks’ path were killed, and typhus was everywhere. The American missionaries took the opportunity to flee to America through Russia [54], and the Rushdoonys went with them, escaping with the help of two old horses that had been left behind by the Russian army. Y. K. used one of them to bring his family to Russia one by one.

Once Y. K. was in Russia, a British officer noticed that he knew English. Among Y. K.’s few possessions was his university degree, and when the British officer saw it, he pulled strings so that the Rushdoony family could travel to Archangel, Russia, where an American missionary named Dr. George C. Reynolds [55] sponsored the family to come to the United States. Y. K. used the dowry of his wife, Rose Gazarian Rushdoony, to pay for their passage to the States. Rose was pregnant with Rousas John when she left for America, and Rousas was born in New York City on April 25, 1916.

While in New York, Y. K. was called to preach at the Armenian Martyrs Presbyterian Church in Kingsburg, California, and later accepted a position at a Congregationalist [56] Church [57] in Detroit, Michigan [58] during the Great Depression.

As the Ottoman Empire crumbled, Armenians, Assyrian Christians, and Greeks continued to be killed and displaced until 1924. By the end of it, Turkey would be almost entirely Muslim. Ethnic tensions persisted between Turks and Kurds, however.

[59]

[59]Location of Greeks in Turkey (purple) and the Armenians (red) before and after the First World War.

Note

[1] [60] Benny Morris & Ze’evi Dror, The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of its Christian Minorities 1894-1924 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2019), p. 116.