Saint Che’s Guide to Asymmetric Warfare, Part 2

Posted By Beau Albrecht On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledPart 2 of 2 (Part 1 here [2])

Why violent accelerationism doesn’t work

Before going further, this is a good opportunity for me to digress regarding certain obvious pitfalls about going postal. Again, I don’t approve of terrorism. As for those who feel otherwise, I note parenthetically that the usual sort of lone nuts have been lousy strategists, no matter what their ideology happens to be. They very seldom make an example out of anyone who personally did anything against their cause. Instead, they typically attack random targets at some public or semi-public space: stores, religious establishments, transit, and so on. Some shoot kids, which is a remarkably efficient way of making everyone loathe them.

Massacring innocents doesn’t advance their cause; instead it gives their opponents a propaganda victory. They undertake what will end with them rotting in prison or, more likely, the grave — and they should be well aware of this. It’s thus grimly paradoxical that they squander their kamikaze missions on random people who never harmed them.

Even The Order, although certainly a cut above the contemporary bumper crop of berserk psych-med addicts, suffered from questionable target selection. They held up an armored car, which was quite a haul. Even so, it was wasted effort, since — apart from unsubstantiated speculation — they didn’t do anything with it, and nobody knows where they stashed the loot. They also whacked some talk show host. What did he do, offend them?

Their Leftist equivalent, The Weathermen [3], did notably better for a while. Still, terrorism didn’t win hearts and minds. They also wasted effort on some targets of questionable value, such as bombing the Haymarket memorial police statue twice. Their downfall began with a fatal mistake while assembling pipe bombs. (I have an idea what might have gone wrong, but the only safety tip I’ll give is don’t make improvised explosive devices.) The group ultimately fizzled out following a bungled armored car heist. Much unlike The Order, the surviving Weathermen terrorists were eventually released from prison. Some members became professors entrusted with teaching America’s youth. It must be nice to be a Leftist!

Consider also the case of John Allen Muhammad and his catamite Lee Malvo, the DC snipers of 2002 [4]. Their murder spree did nothing to benefit their cause. In fact, it would’ve done catastrophic damage to the Nation of Islam’s [5] public relations if the mainstream media was in the habit of reporting anti-white massacres for what they are. Moreover, what if the federal government had taken what had just happened in the nation’s capital, right under their very noses, as a series of politically-motivated hate crimes? Then the entire Black Nationalist movement would’ve been put under the newly-expanded domestic surveillance microscope. Luckily for blacks, their predations against whites — which produce grotesquely lopsided crime statistics [6] — are seldom called hate crimes. Even when blacks target Asians [7], it’s somehow Whitey’s fault, according to The Narrative.

As for the Unabomber [8], his terroristic activities did nothing to advance his cause. A campaign of violent intimidation obviously won’t work if the targets don’t know why it’s happening. Until he published his manifesto, nobody even had any idea that the Unabomber wanted to avert a technocratic dystopia. It didn’t have to be that way. He could’ve written the manifesto long before, not bombed anyone, and put his remarkably spergy but talented mind to becoming a fairly effective activist. Instead of stopping the Fourth Industrial Revolution before it was even a twinkle in Klaus Schwab’s eye, he ended up spending his last days in a prison cell. Luckily for the environmentalists, their cause doesn’t suffer when one of them does something unhinged.

Finally, there was the Las Vegas shooter. Stephen Paddock was in good health, had money, was in an ongoing relationship, and nothing terrible had happened in his life — as far as anyone knows – that was likely to push him off the deep end. Neither was this the result of a sudden burst of rage; surely it took much planning and preparation. That leaves terrorism as a fairly likely possibility. However, it’s uncertain what cause he was trying to serve, or what mundane grudge it was about. If he’d written a manifesto, for all anyone can tell, perhaps it would’ve said that country music sucks. What was the point if nobody knows why? The case is all kinds of hinky, and there has been much speculation. An anonymous tip [9] that emerged before the event — make of it what you will — discusses an upcoming massacre as a psyop intended to sell body X-ray machines to hotels as a security theater measure. But even if that were the original plan, what was in it for the shooter to go on a one-way ride to hell?

The Guerrilla Band

The second chapter opens thus:

We have already described the guerrilla fighter as one who shares the longing of the people for liberation and who, once peaceful means are exhausted, initiates the fight and converts himself into an armed vanguard of the fighting people. From the very beginning of the struggle he has the intention of destroying an unjust order and therefore an intention, more or less hidden, to replace the old with something new.

Some lofty discussion follows about agrarianism, and then:

The conditions in which the agrarian reform will be realized depend upon the conditions which existed before the struggle began, and on the social depth of the struggle. But the guerrilla fighter, as a person conscious of a role in the vanguard of the people, must have a moral conduct that shows him to be a true priest of the reform to which he aspires. To the stoicism imposed by the difficult conditions of warfare should be added an austerity born of rigid self-control that will prevent a single excess, a single slip, whatever the circumstances. The guerrilla soldier should be an ascetic.

Strangely, it’s almost as if St. Che is channeling Captain Codreanu [10]. More of the same follows regarding the sterling qualities expected of guerrilla fighters. This does seem a little much at first glance. Moreover, the Viet Cong got by without doing much on the public relations front, and were more likely to terrorize villagers into compliance. Then again, they had the backing of neighboring North Vietnam, as well as some impressive logistical infrastructure. They had easier access to supplies, and perhaps less need for a network of safe houses than Cuba’s revolutionaries.

[11]

[11]You can buy The World in Flames: The Shorter Writings of Francis Parker Yockey here. [12]

There’s a point here, however. From early on, Castro’s forces made themselves helpful to the peasants, even assisting in education when they weren’t engaged in fighting. The impoverished locals had been neglected by the Batista régime, which was too preoccupied with enriching itself to prioritize social services. Thanks to an effective campaign at winning hearts and minds, the revolutionaries won the public’s support in their area of operation, which is critical for success. If they hadn’t made friends, but instead had busied themselves solely with toting guns while traipsing through the bush, the locals would’ve shunned them as troublemakers. This part is indeed worth a read, and is applicable to non-violent activists as well. As I’ve stated previously [13], we don’t merely need warm bodies; we want people who are in it for the right reasons.

The next subsection, “The Guerrilla Fighter as Combatant,” is considerably longer and discusses military qualifications. For example, it’s preferable for a guerrilla to be from the area he’s operating in so that he knows the territory, he should be accustomed to stealth and night operations, and so forth. Operational security is important, too:

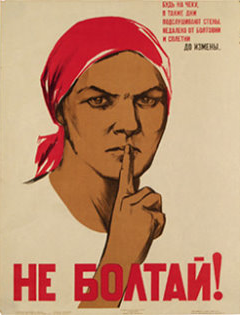

At the same time he ought to be close-mouthed. Everything that is said and done before him should be kept strictly in his own mind. He ought never to permit himself a single useless word, even with his own comrades in arms, since the enemy will always try to introduce spies into the ranks of the guerrilla band in order to discover its plans, location, and means of life.

Remember once again, loose lips sink ships! Much follows about the hardships to be faced, as well as the nuts-and-bolts specifics of how guerrilla operations work. For those interested in military history, it’s a good description of what rebel fighters do and how they get by while roughing it during their campaigns. At the very least, it’ll give some good suggestions on what should go into a bug-out bag.

The third subsection, “Organization of a Guerrilla Band,” describes the ideal size for a foco — that is to say, a guerrilla cell very roughly equivalent to a platoon — and larger subdivisions. (The answer is that it’s complicated.) Again, it’s an interesting read for military history buffs. More practical guerrilla stuff is described: marching formations, combat tactics, etc. Political education is important, too:

The education of the guerrilla fighter is important from the very beginning of the struggle. This should explain to them the social purpose of the fight and their duties, clarify their understanding, and give them lessons in morale that serve to forge their characters. Each experience should be a new source of strength for victory and not simply one more episode in the fight for survival.

One of the great educational techniques is example. Therefore the chiefs must constantly offer the example of a pure and devoted life. Promotion of the soldier should be based on valor, capacity, and a spirit of sacrifice; whoever does not have these qualities in a high degree ought not to have responsible assignments, since he will cause unfortunate accidents at any moment.

That’s another thing applicable to non-violent activism: Participants should know what their cause is all about. Also, they’ll need to earn some street cred before getting into positions of responsibility.

After that is a subsection about combat: basic encirclement tactics, how to use a shotgun to launch a Molotov cocktail, how to evade incoming artillery and air strikes (not such a big problem, in his opinion), and so on. Of course, ammunition is going to be scarce and will mostly need to be acquired from the enemy.

The final subsection is “Beginning, Development, and End of a Guerrilla War,” which is basically what it says on the tin. This describes how the initial guerrilla cell begins as a small band in the remote wilderness, becomes a larger force with a home base, eventually gets to the point where it can make further inroads into hostile territory, and ultimately forces the enemy to surrender. The author also says that in any revolutionary scenario, your mileage may vary with some of that. (That’s very true!) He attributes much of the Cuban Revolution’s success to Uncle Fidel’s wise leadership.

Organization of the Guerrilla Front

The first subsection concerns obtaining supplies. The logistic situation will obviously be difficult. Again, having the backing of the locals is essential:

The first task is to gain the absolute confidence of the inhabitants of the zone; and this confidence is won by a positive attitude toward their problems, by help and a constant program of orientation, by the defense of their interests and the punishment of all who attempt to take advantage of the chaotic moment in which they live in order to use pressure, dispossess the peasants, seize their harvests, etc. The line should be soft and hard at the same time: soft and with a spontaneous cooperation for all those who honestly sympathize with the revolutionary movement; hard upon those who are attacking it outright, fomenting dissensions, or simply communicating important information to the enemy army.

[14]

[14]You can buy Francis Parker Yockey’s The Enemy of Europe here. [15]

Other than that, looting is to be avoided. But it might become necessary to take supplies and write IOUs — “bonds of hope,” as Guevara puts it, which I suppose could also be called extreme store credit. More follows about arranging for the local farmers to produce crops and livestock to support the revolutionaries. (Different arrangements would obviously need to be made in an urban situation.) Some supplies must be sourced from a city, which will necessitate a network of agents.

The next subsection concerns civil organization. This generally concerns administering the territory under rebel control. This is both to serve the military needs of the ongoing revolution, as well as to become the area’s de facto government:

For example, during our experience in the Cuban war we issued a penal code, a civil code, rules for supplying the peasantry and rules of the agrarian reform. Subsequently, the laws fixing qualifications of candidates in the elections that were to be held later throughout the country were established; also the Agrarian Reform Law of the Sierra Maestra. The council is likewise in charge of accounting operations for the guerrilla column or columns; it is responsible for handling money problems and at times intervenes directly in supply.

Indeed, revolutions typically create parallel institutions and eventually supersede the existing ones. For those who’ve dreamed of starting their own country [16], this is the real deal! Those who manage to see things through to victory — in which case the revolutionary state becomes the country’s successor state — they can look forward to having their own statues adorning the Capitol, at last. If they govern wisely, the statues will remain standing after they’re gone.

The third subsection is about the role of women. I might add that St. Che had some experience in that regard. While on the warpath, he took up with a cute señorita. Following the revolution, his Peruvian wife showed up in Cuba, and he had to give her the “Sorry, dear, you’ve been replaced” discussion. During his second marriage, things got lonely on the warpath again. In Bolivia he took up with an East German pinkette. It was a star-crossed romance; her luck ran out soon before his did. His take begins:

The part that the woman can play in the development of a revolutionary process is of extraordinary importance. It is well to emphasize this, since in all our countries, with their colonial mentality, there is a certain underestimation of the woman which becomes a real discrimination against her.

The woman is capable of performing the most difficult tasks, of fighting beside the men; and despite current belief, she does not create conflicts of a sexual type in the troops.

I’m not so sure about all that, but it’s his opinion. He does recommend women for pogue roles such as couriers, messengers, cooks, instructors, and medics.

Next up is a discussion of medical problems. (That’s obviously a concern for a pursuit characterized by dodging bullets.) As might be expected, medical care will be an infrastructure that grows and evolves with the revolutionary forces.

The fifth subsection is about sabotage. He contrasts this with terrorism, which he discourages. In this context, he equates it to random violence, stating that only deserving parties should get whacked. (I wouldn’t even encourage that much. Guevara said it; I’m not fedposting.) Moreover, there’s the cost/benefit analysis to consider:

What ought never to be done is to employ specially trained, heroic, self-sacrificing human beings in eliminating a little assassin whose death can provoke the destruction in reprisal of all the revolutionaries employed and even more.

Beyond that, he describes inanimate targets such as telephone poles, bridges, railroads, and so on. His advice is not too different from that of a sabotage guide, The Freedom Fighter’s Manual [17], which the CIA produced for the benefit of the Nicaraguan Contras. Maybe there was some influence here! If so, St. Che wouldn’t have been amused.

Afterwards is a discussion of war industry. As one might suppose, it begins like this:

Industries of war within the sector of the guerrilla army must be the product of a rather long evolution; they also depend upon control of territory in a geographic situation favorable for the guerrilla.

Manufacturing shoes — and repairing them — is the first order of business. Alongside that will be the production of leather and canvas goods. The next priority is an armory for the repair of weapons and the manufacture of improvised arms. Then there’s a need for blacksmiths and tinsmiths. After that, he recommends setting a shop to manufacture cigarettes and cigars. (This is Cuba, after all!) Other industries will produce leather, salt, and beef jerky.

The seventh subsection discusses propaganda. It goes into detail about target audiences and what should be messaged both inside and outside the rebel zone of control. It might be worth a look, although it’s not especially remarkable.

The next subsection concerns intelligence gathering. Spies are another specialty role, of course. Much can be learned from the locals regarding enemy activities as well. It’s also possible to demoralize the enemy by spreading rumors, and I’ll return to that one at the end.

Following this is a discussion about training and indoctrination. Basically, at first new recruits will get on-the-job training. After the guerrilla forces have grown sufficiently, a boot camp can be established:

These schools then perform a very important function. They are to form new soldiers from persons who have not passed through that excellent sieve of formidable privations, guerrilla combatant life. Other privations must be suffered “at the outset to convert them into the truly chosen.”

After that, it’s the basic boot camp experience, but they’re going to be roughing it a lot out in the open, because that’s what their conditions in the field will be like. He mentions that the location of their training facility was discovered and then experienced frequent air raids, which he says was good practice for the recruits. That’s one way to do a live ammo drill, I suppose . . .

The school for recruits must have workers who will take care of its supply needs. For this there should be cattle sheds, grain sheds, gardens, dairy, everything necessary, so that the school will not constitute a charge on the general budget of the guerrilla army. The students can serve in rotation in the work of supply, either as punishment for bad conduct or simply as volunteers.

Basically, getting smoked will involve peeling potatoes rather than doing pushups. Other than that, Guevara describes a form of target practice without ammunition. I suppose that nowadays, creative use could be made of a laser pointer for similar purposes if you’re feeling too cheap to buy rounds. He also emphasizes the importance of ideological indoctrination:

These courses should offer elementary notions about the history of the country, explained with a clear sense of the economic facts that motivate each of the historic acts; accounts of the national heroes and their manner of reacting when confronted with certain injustices; and afterwards an analysis of the national situation or of the situation in the zone. A short primer should be well studied by all members of the rebel army, so that it can serve as a skeleton of that which will come later.

I would concur that this is important, and for non-violent activism as well. In general, activists of any persuasion should know what their cause is all about and be in it for the right reasons. As for us, perhaps we could start with a brief reading list. Also, might there be some benefit to an initiatory experience for admittance to an activist cadre? It needn’t be a boot camp, but expecting at least a moderate demonstration of personal commitment will help ensure that the members are serious. If it’s easy to join on a whim, it’s easy to walk away on a whim.

The final subsection is “The Organizational Structure of the Army of a Revolutionary Movement” — pretty much what it says on the tin. It ends with a long section about disciplinary punishment. There were a few points where St. Che starts to come across as the sadistic martinet that he was.

Appendices

The first appendix is “Organization in Secret of the First Guerrilla Band,” discussing the circumstances in which active resistance initially begins. Apart from that are some further considerations about launching a do-it-yourself revolution. This is an important point, one of those applicable to non-violent struggle:

Almost all the popular movements undertaken against dictators in recent times have suffered from the same fundamental fault of inadequate preparation. The rules of conspiracy, which demand extreme secrecy and caution, have not generally been observed. The governmental power of the country frequently knows in advance about the intentions of the group or groups, either through its secret service or from imprudent revelations or in some cases from outright declarations, as occurred, for example, in our case, in which the invasion was announced and summed up in the phrase of Fidel Castro: “In the year ’56 we will be free or we will be martyrs.”

[19]

[19]You can buy Alain de Benoist’s Ernst Jünger between the Gods and the Titans here [20].

Basically, the first rule of Fight Club is that you don’t talk about Fight Club, and that’s the second rule, too. Our situation is obviously much different, but although we’re not doing anything illegal, that doesn’t mean we can afford a false sense of security. We’re opposed to the ideology of the globalist power bloc that hijacked our society. But The System is not interested in having a friendly debate. Instead, they’re determined to get their way no matter what — which unfortunately involves running our society into the ground — and they’re not above dirty tricks.

I have a feeling that opsec isn’t taken seriously enough lately. Suppose that the situation deteriorated further than our present concerns such as online censorship, cancel culture, and rigging elections. The day may come when The System rolls out hardcore totalitarianism. If so, how many people would continue making rookie mistakes like gossiping, pillow talk, failing to observe the “need to know” rule, or bringing phones to sensitive meetings?

Appendix 2, “Defense of Power That Has Been Won,” discusses the post-revolutionary Gleichschaltung among the military. Guevara’s take is that the army of the ancien régime will need to be disbanded, though it’s possible for some of its cooperative members to join the victorious guerrilla forces. He warns against “trying to put the new popular army into the old bottles of military discipline and ancient organization.” He doesn’t give any specifics about that, but surely there was a story in it. Again, he recommends political education for new recruits.

Epilogue

After Year Zero had gone by, the author wrote the “Analysis of the Cuban Situation, Its Present and Its Future.” He showcases certain legislative highlights. The first measure was price controls on rent and utilities. Next up was agrarian reform. Although these measures were rather pink around the edges (as might be expected), it’s not so objectionable, other than to richer-than-God landowners.

The great monopolies also cast their worried look upon Cuba; not only has someone in the little island of the Caribbean dared to liquidate the interests of the omnipotent United Fruit Company [21], legacy of Mr. Foster Dulles [22] to his heirs; but also the empires of Mr. Rockefeller [23] and the Deutsch group have suffered under the lash of intervention by the popular Cuban Revolution.

Ooh, burn! Looks like the Deep State types didn’t care for their cash cows getting nationalized. I’ll have to say that if I ever get elected dictator, I’ll be happy to tell our own agribusiness monopolies to fly a kite.

After that, the Epilogue starts delving into post-colonial bilge, but I’ve seen far worse [24]. Then it goes into page after page of pinko bluster.

Guerrilla Warfare: A Method (1963)

The book keeps going and going, and it gets to be a chore. This part begins as a sort of historic overview, and then gets into the author’s take on the situation in Latin America. Further discussion concerns the role of guerrilla warfare in it and the feasibility of pursuing non-violent political solutions. Then St. Che engages in some fedposting:

In these conditions of conflict, the oligarchy breaks its own contracts, its own mask of “democracy,” and attacks the people, though it will always try to use the superstructure it has formed for oppression. Thus, we are faced once again with a dilemma: What must be done? Our reply is: Violence is not the monopoly of the exploiters and as such the exploited can use it too and, what is more, ought to use it when the moment arrives. Marti said, “He who wages war in a country, when he can avoid it, is a criminal, just as he who fails to promote war which cannot be avoided is a criminal.”

After that, the author quotes some fedposting by Comrade Lenin, concluding with this:

That is to say, we should not fear violence, the midwife of new societies; but violence should be unleashed at that precise moment in which the leaders have found the most favorable circumstances.

Much follows about the pragmatic aspects related to that. For one thing, the timing has to be right. He gets awfully long-winded, though occasionally he touches on the theory of guerrilla warfare.

Message to the Tricontinental (1967)

This one is St. Che’s take on the Korean and Vietnam wars, which of course were America’s first spit-in-your-eye wars — and certainly not the last. Much long-winded pinko blather follows, little different from the offerings by our home-grown peace creeps of the time. Amidst that, for a while the subject turns to Africa:

When the black masses of South Africa or Rhodesia start their authentic revolutionary struggle, a new era will dawn in Africa. Or when the impoverished masses of a nation rise up to rescue their right to a decent life from the hands of the ruling oligarchies.

Yeah, turned out great [25], didn’t it? Then there’s considerable moaning about Yanqui imperialism. Getting towards the home stretch:

We must carry the war into every corner the enemy happens to carry it: to his home, to his centers of entertainment; a total war. It is necessary to prevent him from having a moment of peace, a quiet moment outside his barracks or even inside; we must attack him wherever he may be; make him feel like a cornered beast wherever he may move. Then his moral fiber shall begin to decline. He will even become more beastly, but we shall notice how the signs of decadence begin to appear.

Precious, isn’t it? Consider it a reminder that the Leftist agenda doesn’t sleep.

Summary

All told, the book gives a good overview as well as a micro-level take on the theory and tactics behind the Cuban Revolution. A careful understanding will illustrate the preconditions which made it work, while certain copycat revolutions fizzled out and ended in disaster. Still, may the buyer beware. The tactics are dated, of course, since the main body of the text was written in 1961. Moreover, the book makes it sound too easy, which can lead to overconfidence.

There’s one thing that needed some more attention. Within two years, their initial force grew from approximately 20 guerrillas to an army with its own turf and infrastructure that was poised to take over Cuba. Conditions were ripe, of course, with the government being vastly unpopular and the impoverished farmers being so desperate that they had nothing to lose. But I would’ve liked to see some more focus on how their recruitment efforts worked, since that was obviously instrumental to success. Perhaps St. Che’s further memoirs, Episodes of the Cuban Revolutionary War, might have some answers regarding that.

Again, certain principles here are applicable to non-violent struggle as well. One thing that looks interesting was the spreading of false rumors to the enemy — black propaganda, in effect. Back in the Communist days, government agencies such as the Stasi and the KGB tracked dissidents. Early on during the Red Terror, an anonymous tip could lead to a summary execution. Why didn’t anyone think of accusing some deserving parties, as for example by tattling on the nastiest Communist thug in the neighborhood for being a secret subversive, or even saying that Lavrenti Beria was a double agent? That was a lost opportunity to get the revolution to eat itself, but something similar is possible now.

There are presently a number of well-funded groups which busy themselves with doxing political dissidents, smearing them, and sharing information with domestic spying operations. Unlike totalitarian countries that rely on government agencies to do all the work, Our Democracy ™ features bottom-feeder private organizations that help spy on citizens for free. They’re not limited by due-process rules or constitutional protections that the government is bound by. Social Justice Warrior e-mail lists are another blight, and are instrumental to cancel culture. To make them look like a bunch of monkeys, all it would take is a few people who regularly use burner e-mail accounts to feed them disinformation, such as reporting fictitious organizations, outing eminently deserving Leftist douchebags as having politically incorrect views, and so on. That’s fifth generation warfare. ¡Venceremos!