A Glimpse of the State of the US in 1885

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right1,736 words

Josiah Strong

Our Country

New York: The Baker & Taylor Company, 1885

In the period between the Civil War and the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the division between Left and Right in the United States had a different arrangement than today. William Jennings Bryan [2], for example, was a man of the Left, but Leftists would disavow his intense religious faith today.

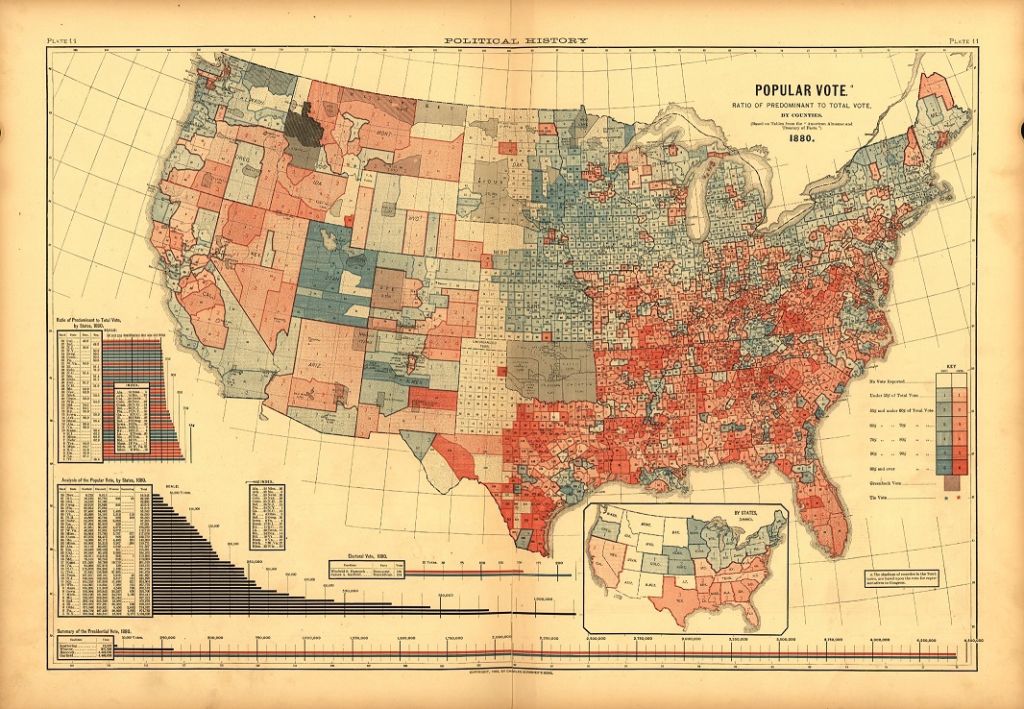

The main reason for this difference is because at that time all sides of the political elite buried race issues. The American Majority announced that they’d dropped the sub-Saharan uplift schemes [3] when President James A. Garfield [4]’s statements about “civil rights” were unenthusiastically received by several different constituencies. Americans decided to focus on white accomplishment rather than endless babysitting of blacks.

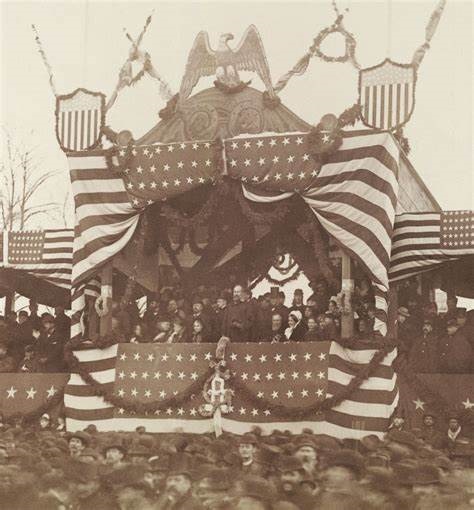

[5]

[5]James A. Garfield had a short presidency, as he was mortally wounded by a “disappointed office seeker” four months after being inaugurated. Garfield is notable in that he campaigned and supported “civil rights,” but quietly dropped the matter when he realized that most of the American public was tired of sub-Saharan uplift efforts.

The Right of the era can be discerned by boiling down the issues to their essentials. These issues include developing a political philosophy that was aligned with the interests of a single ethnic group, in this case that of Yankees [6]. It also includes support for national unity, rationally identifying problems, and developing feasible solutions, as well as the expansion of national power. By that definition, Josiah Strong [7] was one of the most prominent Right-wing thinkers [8] of his time, although he called his ideas the Social Gospel [9]. Perhaps a better reason to call him “Right wing” is that modern academics call him an “imperialist” and “nativist.”

Josiah Strong was born in Naperville, Illinois to a Yankee [10] family [11] that had originated in colonial Connecticut [12]. He attended Western Reserve [13] College [14] and Lane Theological College. Strong was a Congregationalist. He pastored a church in Wyoming [15] and then returned to Ohio to take another pastorship. While in that capacity, he became involved with the Congregationalist Missionary Society. When he was asked to update a missionary manual, it became Our Country, published in 1885.

[16]

[16]The Congregationalist denomination can be seen as a proxy for New Englanders, whose roots in America extend back to colonial times. Its membership has been continuously raided by more vigorous Protestant sects.

Our Country turned out to be enormously influential. After reading it, I realized that Strong’s ideas continue to be preached in some form in every American Protestant faith, most of the members of which are American Majority whites who likely have ancestors who were Congregationalists. The Congregationalist denomination is a moderate form of Protestantism. Its membership began to be raided by other denominations after the New England states disestablished their state churches. Congregationalism’s philosophical and theological reach in America is enormous, but hidden under the surface.

Strong starts his book with an examination of the improvement in the Anglo-Saxons’ economic and social circumstances. In the early seventeenth century, a man could be hanged for poaching a rabbit and a wife could be sold into servitude by her husband.

[17]

[17]The First Congregational Church in Cheyenne, Wyoming. This was the first church that Josiah Strong pastored after graduating from seminary. Strong’s experience in the West had shaped his philosophy.

America’s western potential

The United States had only 38 states in 1885. The western parts of the country were still being settled, and much of the region appeared to be a windswept waste. After his experience in Cheyenne, Strong recognized the region’s vast potential. He pointed out that the railroads rendered mineral mining in the region possible, since heavy machinery could then be easily brought to the mountains and the minerals themselves could be quickly transported to factories in the east. Additionally, he pointed out that the American West was not really a desert, but rather a vast prairie [18] that could sustain crops, especially if wells were sunk for irrigation.

Much of Our Country focuses on America’s West. He mentions the Dakota Territory [19], Nebraska, Kansas, and Arizona more than any other group of states. He also mentions specific Western American conditions, such as a high ratio of saloons per capita and rampant land speculation. He makes little comment on the Indians, although the Indian Wars [20] were still ongoing. Strong points out that the free land [21] on the frontier was running out in 1885, and that its subsequent closure would have an impact on American domestic politics [22].

Strong lists America’s problems of America in 1885 on a half-sheet of notepaper: immigration, Catholicism, Mormonism, intemperance [24], socialism, wealth, and rampant urbanization. His emphasis on immigration [25] is mostly related to the number of new arrivals, the problems with the growth of cultural enclaves that were alien to the rest of America’s traditions, crime, and the fact that the immigrations tended to be European Catholics who liked to drink — especially the Germans and Irish. Strong argued that advances in steam engine technology were creating a pool of surplus laborers in Europe, and that many of those laborers wished to move to the United States. He also pointed out the enormous problems within Europe that were fueling the migration flows. Russia in particular was a volcano of revolution and instability even as early as 1885.

Strong saw America in Anglo [26]–Saxon [27] terms, and he understood that American Anglo-Saxons could still easily assimilate many of the newcomers. The Germans, according to Strong, become Anglo-Saxons after their first generation in America. [28] Strong points out that Anglo-Saxons in Great Britain had been assimilating the nearby peoples of Europe for a very long time:

. . . Mr. Tennyson’s poetic line, “Saxon and Norman and Danes are we [29],” must be supplemented with Celt and Gaul, Welshman and Irishman, Frisian and Flamand [30], French Huguenot and German Palatine. What took place a thousand years ago or more in England again transpires today in the United States.” (171)

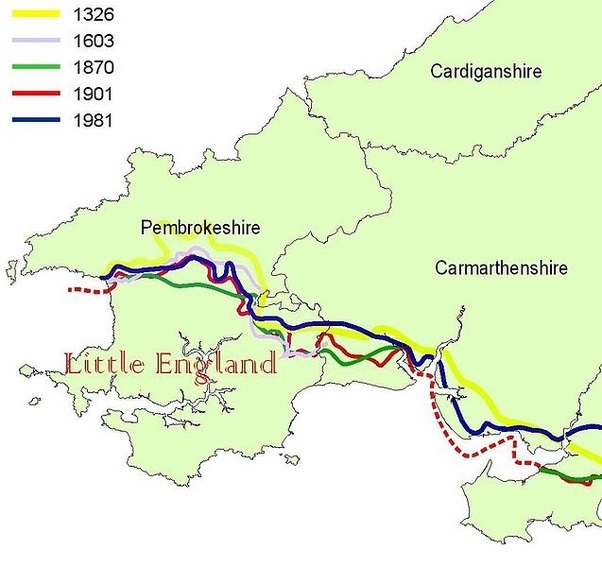

The first Anglo-Saxon(ish) settlement outside of England was not in Ireland, but in the southern part of Pembrokeshire in Wales. King Henry I resettled Flemish immigrants in a part of Wales that was already home to small communities of Norse, Saxon, and Irish settlers as early as 1135. The community this combined group created became English-speaking and aligned with Anglo-Saxon folkways. The area is still called Little England Beyond Wales [31] today.

[32]

[32]The southern part of Pembrokeshire in Wales has been culturally Anglo-Saxon for more than a thousand years. Little England Beyond Wales is a region of Great Britain whose cultural and ethnic heritage is remarkably similar to that of the United States: a founding stock of Anglo-Saxons alongside other assimilated northern European peoples, including the Irish.

Strong doesn’t focus on immigrants who could not possibly assimilate. He doesn’t mention Indian or sub-Saharan issues at all. He likewise fails to notice the Jewish problem. Any reference to Jews in Our Country tends to be in the form of a Biblical analogy. Strong’s critique of immigration is the first serious work on the matter, however, and it would be up to other writers, such as Madison Grant [33], Lothrop Stoddard [34], Wilmot [35] Robertson [36], and [37] others [25], to add more nuance to the issue.

[38]

[38]You can buy H. L. Mencken’s The Passing of a Profit and Other Forgotten Stories here [39].

Strong’s critique of Mormonism and Catholicism has nothing in to do with theology. He merely points out that the Mormons were practicing polygamy, which creates social problems, especially because it leads to the creation of a group of young, unmarried men who are willing to make trouble. He also criticizes Mormon political organization, which reinforced polygamy and swung local politics in their favor. Strong has no criticism of the Mormon “Josephites [40]” who rejected polygamy and still have a large settlement in western Missouri today. As for Catholicism, Strong is critical of the Church authorities’ hostility to Protestantism and suppression of public education, free speech, and republican institutions.

Strong writes in depth about the problem of alcoholism. He shows that during the nineteenth century, consumption of hard liquor increased across the English-speaking world, causing a variety of social ills. All of this is true, of course, but Strong is clearly in favor of temperance — the reduction of alcohol use — rather than prohibition. Strong’s points out that advocates of temperance in 1885 could, in modern terms, be “cancelled” by the liquor lobby. Those getting “cancelled” now can take courage in the fact that socially responsible men and women of the past were “cancelled,” too, and yet their cause went on to triumph.

His description of socialism’s problems does not relate to its economic inefficiencies. In 1885 the particulars of rent-seeking, support for unprofitable industries, and so on were still unknown. Although in Chicago in the 1870s, socialists, who were mostly ethnic Germans, had created an armed militia [41] and advocated for violence.

After criticizing socialism’s armed followers, Strong looks at America’s wealth inequality and is highly critical of the situation. Strong’s moral condemnation of big capital’s excesses is so clearly argued that within 15 years, progressives in both parties would create trust-busting and anti-monopoly laws that they would go on to zealously enforce for the next century. Strong also looks at urbanization and the problems with sanitation, housing, divorce, and disease resulting from it. He likewise proposes child labor laws and recommended education for all classes.

Strong’s predictions miss the mark in some unfortunate ways, however. In 1885 it was still possible to believe that the growth of “Anglo-Saxon” whites (by this he means white English-speakers) would continue at a high rate. Strong points out that in 1700 there were less than 6 million Anglos; in 1800, there were 100,000,000 (161). He predicted that America would have 480,000,000 English-speaking whites by 1980, a mark which was not reached (185).

Strong didn’t recognize what was happening. After the Civil War, old-stock American population growth dropped off for a time. American Majority community leaders such as Edward Alsworth Ross [42] and others had to push to get the birth rate up in the following decades. At the same time, British economic power was declining [43] while Britain’s leadership was making poor choices [44].

Our Country does, however, correctly predict that America’s work ethic, especially as it related to its large agriculture and manufacturing sectors, was putting the United States on the path to superpower status, although Strong didn’t use these exact words. America remains a superpower on paper today, but its empire is one of rust, cobwebs, and dysfunctional and expensive clients. America has too many allies with too many problems, and its political elite despises [45] the American whites who keep the machine running. American whites must act and think anew to respond.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [46]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[47]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[47]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.