Ba’athism and Saddam Hussein: A System that Worked, Part 1

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled [1]

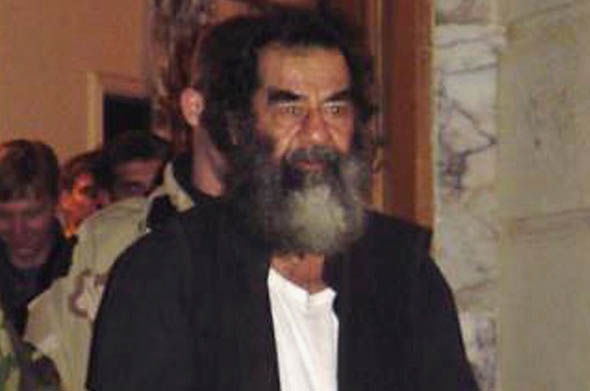

[1]Saddam Hussein was captured on December 13, 2003. Things have not gone well for Americans in the two decades since.

2,835 words

Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here [2])

It’s been 20 years since the United States military captured Saddam Hussein. The Iraqi dictator was captured by the American 4th Infantry Division along with commandos from a special forces unit, Task Force 121 [3], at the end of a nationwide manhunt that lasted for eight months after his regime had been toppled. For months, American intelligence agencies had suspected that Saddam, who had disappeared from public view after Baghdad was captured by coalition forces, was in hiding somewhere near Tikrit, but patrols and raids had turned up nothing. Eventually the Americans adopted a strategy of capturing people who knew the whereabouts of those who were likely helping Saddam. The wider network of Saddam’s supporters was thus unraveled, and Saddam was eventually pulled out of a hole in the ground.

In the immediate aftermath of Saddam’s capture, the occupying forces ceased all offensive operations with the idea that the insurgency that had been building would then run out of steam. It didn’t, unfortunately. After several days, offensive operations resumed, and the war ground on for eight more years. Not only was the Americans’ assumption that Saddam’s dictatorship was the cause of the Middle East’s problems wildly wrong, but their belief that Saddam himself was leading the insurgency was also incorrect. Hussein would be hanged on December 30, 2006 after being found guilty in an unjust political trial, and Iraq — and America’s — problems continued to metastasize.

[4]

[4]The capture of Saddam Hussein was initially greeted with euphoria, but the problems in Iraq continued.

The unsatisfactory results following Saddam’s capture are significant. They highlighted the fact that, in some cases, autocracy is better than a democratic form of government. They also showed the importance of the ethnic and religious differences that Saddam had (mostly) managed to suppress throughout his reign, as tensions between groups exploded to the forefront of Iraqi society once he was gone. They also laid bare the fact that American foreign policy is dominated by pressure groups advocating for the interests of foreign countries. And finally, they marked the end of America’s Wilsonian idealism — the idea that American ways are always the right solution in any situation.

Saddam, the “Next Hitler”

During the better part of a decade prior to his capture, Saddam was the big, bad enemy [5] of the United States, being described as such by the mainstream media and other upstanding “patriotic Americans” who just “happened to be Jewish” and had extensive ties to Israel. The vilification of Iraq’s Ba’athist regime began during the 1990-91 Persian Gulf War [6], when George H. W. Bush’s administration as well as American propaganda painted Saddam as the Anti-Christ.

In the lead-up to the Iraq War in 2002-2003, the moral fury against Saddam was everywhere in America, fueled by the misapprehension that he had been involved in the 9/11 attacks and fanned by George W. Bush — coincidentally, again with a cohort of politically-active Jews. This fury drove the national conversation in the mainstream media outlets, all of which said the same things.

A good example of this was a March 2003 article by Thomas P. M. Barnett in Esquire magazine [7], in which he wrote: “Saddam Hussein’s outlaw regime is dangerously disconnected from the globalizing world, from its rule sets, its norms, and all the ties that bind countries together in mutually assured dependence.” Barnett also called Saddam “a cutthroat Stalinist willing to kill anyone to stay in power . . .” Barnett made the case that one purpose of an invasion of Iraq would be to connect the country to the larger community of functioning “core states.” [8] He concluded with a quip:

Show me a part of the world that is secure in its peace and I will show you strong or growing ties between local militaries and the U.S. military. Show me regions where major war is inconceivable and I will show you permanent U.S. military bases and long-term security alliances.

Barnett’s ideas, which were typical of American thinking at the time, were mostly bad ones, and the policies that were derived from views such as his started to shrivel and die during the first year of Bush’s second term [9]. In retrospect, Barnett’s invective was unwise considering the disasters that followed Saddam’s ouster.

Ideas about “core states” and countries such as Iraq that were disconnected from them were merely cover stories, however. The real reason why Saddam was so hated by the American political establishment was because politically-active Jews [10] disliked the man [11] and his party. They saw that he was an effective leader of an Arab nation, and had the ability to threaten Israel.

[12]

[12]A crater left by an Iraqi Scud missile in Israel during the Persian Gulf War. The Gulf War marked the moment when Israel unquestionably became a strategic burden to the US.

It is important to point out that Saddam’s goals were not in line with any of the goals of the dissident Right. He was not a man of European heritage; he was not a member of Western Civilization. He also made enormous geopolitical mistakes. Saddam was not a democrat who ruled his people with enlightened liberty and free speech. He really had secret police, torture chambers, and political prisoners. Nonetheless, prior to his invasion of Kuwait in 1990, Iraq was connected to global trade, and supported by the international community.

Contrary to American propaganda, Saddam Hussein was in fact a rational actor. He vigorously pursued Iraq’s interests as they were understood by its socially-dominant Sunni Muslim core. He also successfully applied the ideology of Ba’athism in order to stabilize his country. Even his political purges and his use of a secret police force were carefully planned policies. Before 1990, his regime was part of the global trade network and was respected by the international community.

To understand Saddam, one needs to understand Iraq’s modern history as well as the Arab nationalist ideology of Ba’athism.

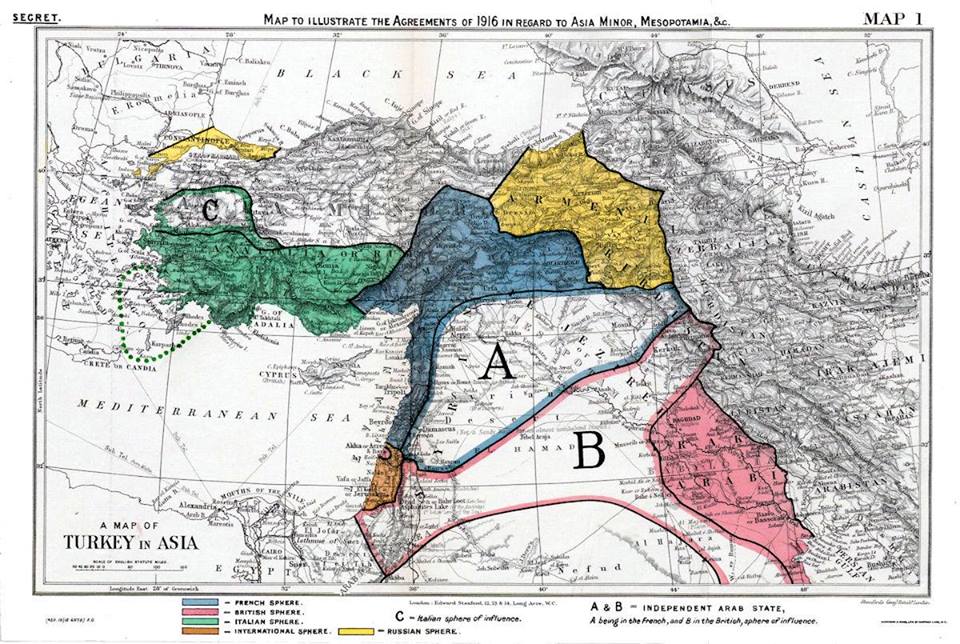

[13]

[13]The Sykes-Picot Agreement divided the Arab segments of the Ottoman Empire into regions controlled by France or Britain under mandates. The agreement would establish what ultimately became the Middle East’s modern polities.

The Fatal Flaws in Modern Iraq

[14]

[14]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Toward a New Nationalism here [15].

Modern Iraq was established by the British out of a part of the Ottoman Empire’s Arab territories which they had captured during the First World War. Iraq’s primary developer was an extraordinary Englishwoman named Gertrude Bell [16]. Despite the best efforts of Bell and the British government, there was a ferocious insurgency against the British in Iraq [17] in 1920. In response, a British-aligned monarchy was set up to politically stabilize the situation. The Iraqi royal family then bumbled along [18], facing anti-British and Arab nationalist insurrections on several occasions. The monarchy ended in 1958 following a coup, which will be discussed further on.

The Iraqi monarchy had several fatal flaws. Its royal family were outsiders who had come to power through the patronage of a foreign imperial power which was itself already rapidly declining [19], although its decline was only clear in retrospect [20]. They also failed to establish a loyal military, and invited disloyalty by not fielding two armies which each had separate chains of command but still reported to the king.

The early Republic of Iraq, in the years after 1958, likewise had a fatal flaw. It had come about through a lawless, violent coup, and as a result there was nothing to stop more coups from following.

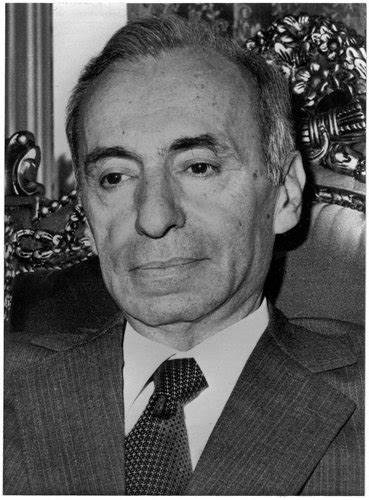

The Rise of Ba’athism

The term Ba’athism is derived from the Arabic al-Baath al-Arabi, or “Arab resurrection.” It is a relatively successful political theory which was developed by three Syrian Arabs.[1] [21] There was Michel Aflaq [22], a Greek Orthodox Christian from Damascus; Salah al-Din Bitar [23], a Sunni Muslim from the Maydan quarter of Damascus [24]; and Zaki Arsuzi [25], an Alawite [26] from Alexandretta [27]. All three were educated at the Sorbonne in Paris. They were never members of the same political party, and had numerous feuds and reconciliations throughout their careers, although Bitar and Aflaq often worked together. They were not politically successful in their own right, however. When Aflaq ran for office in 1943, he only secured 245 votes. Bitar won a parliamentary seat in 1945, but barely.

Ba’athism is strongly influenced by European and American political thought, its ideals resembling the metapolitical narratives [28] that appeared during the Revolutions of 1848 [29] and which led to the unification of Germany and Italy. The early Ba’athists sought to unify the whole of the Arab world from Morocco to the Iran-Iraq border in a single political unit. They also rejected monarchy and the class system; Syria was still mostly a feudal society in the 1940s. Ba’athism also sought to establish a socialist society. The ideology acknowledges the importance of Islam in the Arab world, but Arab ethnonationalism is at its center.

This led to tension between Arab nationalism and universalist Islam, a problem which has never been resolved. As John F. Devlin writes in his history of Ba’athism:

[The Ba’athist] view of Islam was hardly likely to appeal to the orthodox Muslim. But Aflaq and his followers were not speaking to the orthodox. Their audience, their potential adherents, were young, educated in schools heavily influenced by Europe and America, men to whom traditional Islamic practices and beliefs were largely irrelevant.[2] [31]

[32]

[32]Rusting rail stock on the Hejaz Railway, which was destroyed by Arab nationalists backed by the British during the First World War. The Hejaz Railway was emblematical of the tensions between Islam and Arab nationalism: built with money from Muslim donors, it was meant to allow Muslim pilgrims to travel more easily to Mecca, but it also threatened local Arab interests.

The success of Ba’athism had more to do with its followers than its founders, Although Bitar, Aflaq, and Arsuzi were often at odds, they had followers among prominent Arabs who attended all three men’s meetings and studied their writings. They were usually from the prestigious city of Damascus, and had gone to the top secondary schools. They also tended to be middle class, educated, and skilled in technical trades. Many of the first Ba’athists were civil servants in Syria.

Ba’athism spread through other means as well. The Levant, of which Syria is a part, had a better public education system and technical training than most of the Arab world. Thus, Syrian teachers — usually those influenced by Bitar, Aflaq, and Arsuzi — would go on to become instructors in Iraq and Jordan. By 1945, when the European empires were in ruins, Ba’athism was well-positioned to make real gains.

[33]

[33]Aflaq organized likeminded students and published works propagating his views, which amounted to three points: freedom from European colonial rule, a pan-Arab political union, and a socialist economic system for Arabs — national socialism — and a non-atheistic government that was nevertheless secular.

These gains did not come easily, however. Ba’athism was a threat to the feudal order in Syria, and thus the wealthy elite fiercely resisted its spread and rise. There were also many competing political parties across the Arab world. For a time, Ba’athism was suppressed; its newspapers were shut down in the 1950s, its writers were forced to publish under pseudonyms, and civil servants who were sympathetic to it were dismissed if they were discovered. Aflaq and Bitar went into exile in Lebanon.

The Man on a White Horse

In 1958, the Ba’athist Party made its first serious mistake. The Ba’athists named Egypt’s President, Gamal Nasser [34], as their leader, although he was not himself a Ba’athist. Nasser had risen to the presidency by deposing the Egyptian King in 1952. In 1956, Nasser defeated a combined British, French, and Israeli attempt to capture the Suez Canal for themselves. Thus, Nasser’s star was indeed high in the late 1950s. The Ba’athists then attempted to unite Syria and Egypt in a single nation, which became the United Arab Republic in 1957.

This union’s problems manifested immediately. The Syrians were accustomed to a federal political system and French-style government. The Egyptian government, however, was centralized and in the British style. Nasser likewise didn’t believe in political parties, so the Ba’athists disestablished their political machinery and imperfectly communicated their ideas through the Arab media. Despite Nasser’s earlier achievements, the political situation in the Republic became increasingly unstable. Finally, in 1961 Syria withdrew. The Ba’athists had to restart their party in 1963, and it effectively became a new organization.

Early Ba’athism in Iraq

Ba’athism trickled into Iraq in the early 1950s via the efforts of Syrian teachers. The movement was mostly underground at first, but as in Syria, it captured the minds of the educated middle classes. In Syria, Ba’athism was a movement that crossed religious boundaries. In Iraq, it instead became the political expression of the Sunnis and Iraqi Christians. Ba’athism had many supporters in Tikrit, which was Saddam’s hometown.

Ba’athism remained minor in 1950s Iraq. In 1958, the Iraqi military organized a coup against the King. The royal family was executed, and Abd al-Karim Qasim, a senior officer, took power. Qasim’s ascension via a coup set the tone for his otherwise progressive rule. Once a transfer of power takes place through non-constitutional means, whether it is a violent coup or obvious election fraud [36], the political temperature not only rises, but every faction is tempted to either carry out an assassination or organize a coup themselves.

Qasim’s first major problem was his fellow conspirator, Colonel Abdul Salam Arif. In 1958, Arif was commanding the battalion which actually carried out the coup. As a result, Arif felt he should be the one in power. Resentments and rivalry grew between Qasim and Arif throughout the former’s regime. There was even an assassination attempt on Qasim by Ba’athists in 1959, and Saddam Hussein was almost certainly personally involved. The plot failed, however, and many Ba’athists were arrested, went underground, or went abroad afterwards.

Qasim did many of the same things that Saddam did later, although he commonly pardoned opponents, rioters, and other political dissidents. Shortly after rising to power, he was forced to go to war against the Kurds, as Arab nationalism didn’t play well with the Indo-Europeans in Iraq’s mountainous northeast. In 1961 Qasim threatened to invade Kuwait, which had recently gained independence from the British Empire. The new Emirate, however, had good relations with the British, and British troops returned to the region to deter an Iraqi invasion [37].

[38]

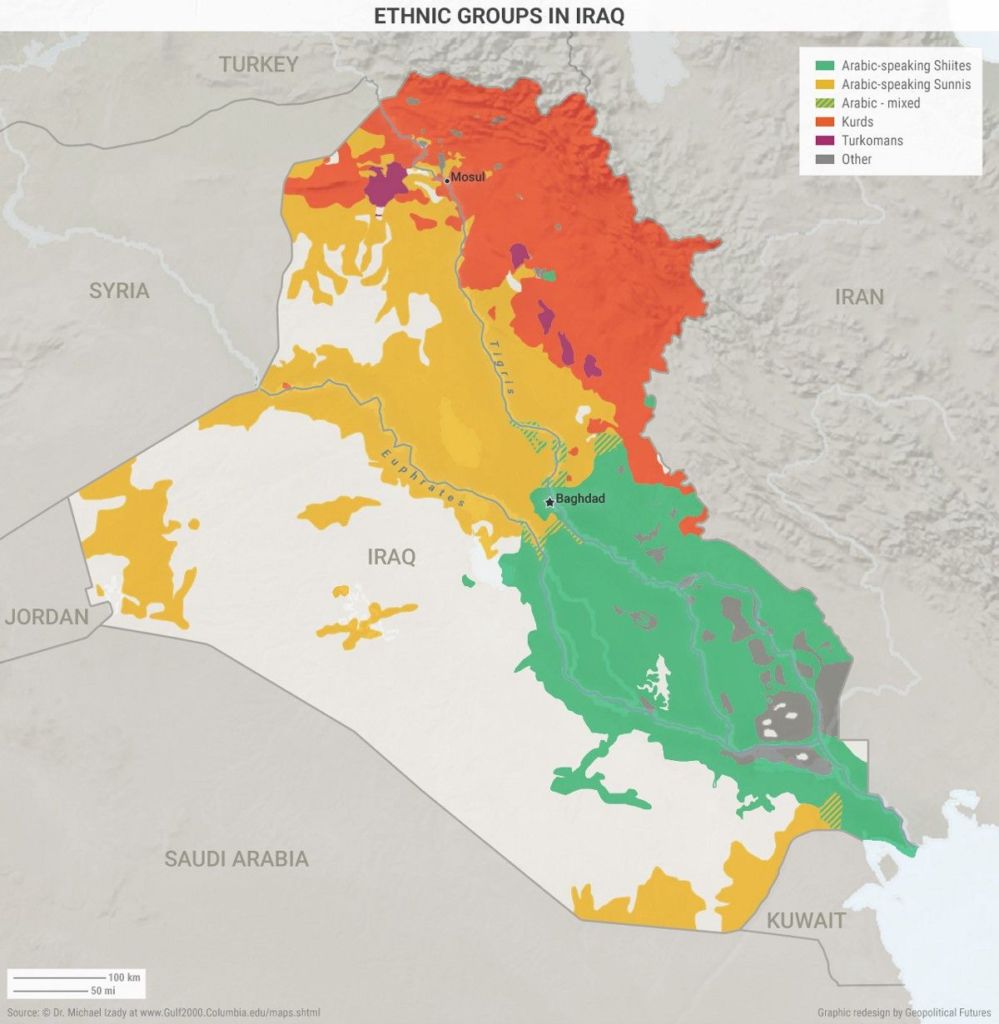

[38]The major ethnic and religious groups and their locations in Iraq. Qasim’s coup determined Iraq’s national policies for the next five decades. Kurdish rebellions began as early as 1960 and have never ceased.

Qasim was an Arab nationalist, but not a Ba’athist. He carefully balanced non-Ba’athist and Communist political elements, but still had problems with the latter. They rioted in the streets of the cities and otherwise made trouble. Qasim’s alignment with the Soviet Union and his threats to nationalize the oil industry triggered another coup, this time against him. There is considerable evidence [39] of CIA involvement in organizing it, [40] and given that the Soviets supported Qasim’s regime, it is likely. Thus, the Baathists took power in 1963.

Ba’athists in the Iraqi military executed Qasim — albeit not without a fight with his supporters — and made the non-B’aathist Abdul Salam Arif the country’s President, which was purely a symbolic position. The Ba’athists then created a National Guard, which was sympathetic to Ba’athism, its ranks being filled by educated young men. Its purpose was twofold: to create a separate military to secure the Ba’ath Party, and to convince educated Iraqis to support the coup [41]. The National Guardsmen patrolled the streets of Baghdad, checked paperwork, and otherwise kept order.

Arif quickly outmaneuvered the Ba’athists. He restructured the military command and other government ministries, filling key positions with non-Ba’athists. In the meantime, the National Guard had alienated the public. Within nine months, Ba’athist control of Iraq had ended.

As John F. Devlin writes:

The nine months of Baathist rule had little constructive impact on Iraq, the party leadership was divided in outlook, preoccupied with internal squabbles, fearful of accepting other Iraqis as partners, and incompetent in the art of governing. No laws of importance were passed, nor any reforms of consequence. In a sense, Arif’s regime was the successor to Qasim’s; the Baath interlude was, as it were, a preliminary act that almost everyone forgot when the main attraction [in 1968] came on. But that interlude, with its strong-arm repression of the Communists and the institutionalized violence of the National Guard, contributed to the cycle of political murder and repressive government [that became evident after 1968.][3] [42]

Notes

[1] [43] The prominence of Syrian Arabs in developing pan-Arab ideology is not an accident. Prior to the Sykes-Picot Agreement, “Syria” was a term that encompassed a larger region than today’s Syria. As Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr. and Lawrence Davidson wrote in their book, A Concise History of the Middle East: “The ones whose role mattered most in the birth of Arab nationalism lived in greater Syria, which then included most of what we now call Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, the Republic of Syria, and even parts of southern Turkey” (p. 199).

[2] [44] John F. Devlin, The Ba’ath Party: A History from Its Origins to 1966 (Stanford, Calif.: The Hoover Institution Press, 1974), p. 276.

[3] [45] Ibid.