Thomas Nelson Page’s Social Life in Old Virginia Before the War

Posted By Beau Albrecht On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled4,261 words

What was life like in the antebellum South? Obviously it’s going to be a matter of perspective. Thomas Nelson Page [2] provided one such viewpoint, the type we seldom hear about lately. He was a lawyer in his early career and a diplomat later, but is best known as a writer.

Aside from several novels, he published a non-fiction account of the Old South as he remembered it during his boyhood. This was Social Life in Old Virginia Before the War [3] (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1897). It’s a quick read, providing a glimpse into a bygone time. The several figures it describes as typical people you’d find on a plantation seem to be composites of the author’s household and neighboring households with which he was familiar.

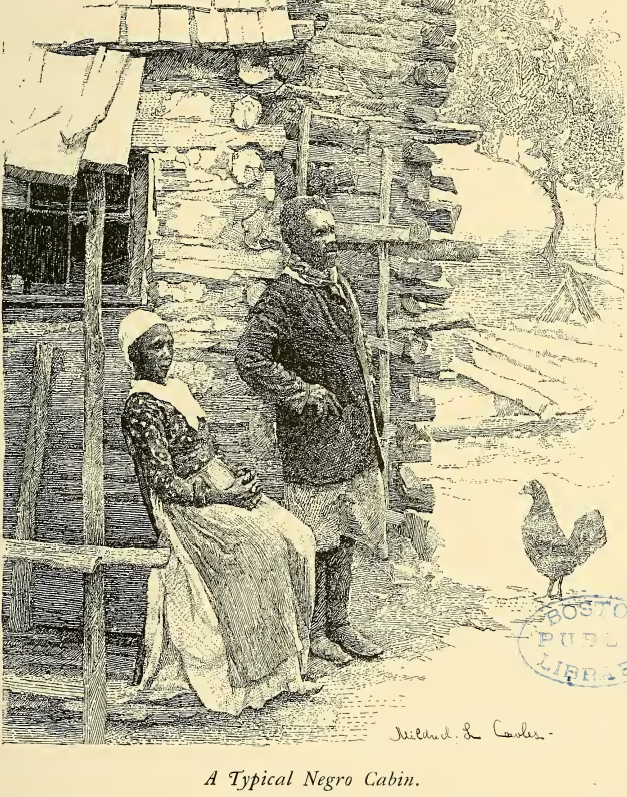

Several skillful illustrations are included. These were drawn by “The Misses Cowles,” an artistically-inclined family [4] that included four sisters. A contemporary source describes their works:

The two elder girls . . . have met substantial recognition . . . the two younger girls have shown a lightness and humor more distinct from the efforts of the older sisters. The pastoral sympathy and grace, the love and understanding of woodland things and their subtle relation to human beings, are all discernable in their work; the humanness of life, the pathos and the tread of wayfaring folk being also shared by all. If there be any appreciable divergence, it is the feeling that the younger girls stand nearer to the world and to a more realistic view of it.

Their illustrations in the book live up to these descriptions.

Preface

Early on, Page gives some reasons why he wrote Social Life in Old Virginia Before the War. He had a motive besides encouragement by his friends:

Another is the absolute ignorance of the outside world of the real life of the South in old times, and the desire to correct the picture for the benefit of the younger generation of Southerners themselves. One of the factors in that life was slavery. The most renowned picture of Southern life is one of it as it related exclusively to that institution. As an argument in the case then at bar, it was one of the most powerful ever penned. Mrs. Stowe [5] did more to free the slave than all the politicians. And yet her picture is not one which any Southerner would willingly have stand as a final portrait of Southern life. No one could understand that life who did not see it in its entirety.

Indeed, as the author was beginning to observe already even in his time, the antebellum South has come to be seen as all about one thing only. He was right to preserve the memory of the way things were for benefit of posterity:

Quite a large crop of so-called Southern plays, or at least plays in which Southerners have figured, has of late been introduced on the stage, and the supposititious Southerner is as absurd a creation as the wit of ignorance ever devised. The Southern girl is usually an underbred little provincial, whose chief characteristic is to say “reckon” and “real,” with strong emphasis, in every other sentence. And the Southern gentleman is a sloven whose linen has never known starch; who clips the endings of his words; says “Sah” at the end of every sentence, and never uses an “r” except in the last syllable of “nigger.” With a slouched hat, a slovenly dress, a plentiful supply of “sahs,” and a slurred speech exclusively applied to “niggers,” he is equipped for the stage. And yet it is not unkindly meant: only patronizingly, which is worse.

The distortions he was noting as early as 1897 go much further in recent decades with TV and especially film. This time the “hillbillies with tobacco juice dribbling down their chins” stuff is indeed meant unkindly. On the other hand, the biased characterization of the Old South as an unrelenting chamber of horrors is small potatoes compared to what Hollyweird does to Germany.

Down home

The author begins describing the plantation estate. There’s a fairly brief description of the rustic mansion itself, as well as its furnishings. Much more of the prose is about the Sun-dappled land itself, waxing quite lyrical in many places. Here’s the description of the flower garden:

It was a strange affair: pyrocanthus hedged it on the outside; honeysuckle ran riot over its palings, perfuming the air; yellow cowslips in well-regulated tufts edged some borders, while sweet peas, pinks, and violets spread out recklessly over others; jonquilles yellow as gold, and, once planted, blooming every spring as certainly as the trees budded or the birds nested, grew in thick bunches; and here and there were tall lilies, white as angels’ wings and stately as the maidens that walked among them; big snowball bushes blooming with snow, lilacs purple and white and sweet in the spring, and always with birds’ nests in them with the bluest of eggs; and in places rosebushes, and tall hollyhock stems filled with rich rosettes of every hue and shade, made a delicious tangle. In the autumn rich dahlias and pungent-odored chrysanthemums ended the sweet procession and closed the season.

After that, the author starts going into detail about the plantation’s roses in their several varieties, which by itself is quite stunning. With a little imagination, reading the description that he wrote from memories of his youth is — as intended — much like a trip to another time and place. Beyond the literal meaning of the words, for me it evoked the very essence of the rose: conjuring forth its beauty and fragrance, its aura of silent mystery, its nature both placid and wild, and its exuberant life force burgeoning forth under the Sun. Surely the presence of Goddess Herself can be felt in a rose garden like that! (Merely trying to recount my impression of his description has me a bit overwhelmed.) After that, the author too finds himself out of words, so he quotes Dr. George W. Bagby:

A scene not of enchantment, though contrast often made it seem so, met the eye. Wide, very wide fields of waving grain, billowy seas of green or gold as the season chanced to be, over which the scudding shadows chased and played, gladdened the heart with wealth far spread. Upon lowlands level as the floor the plumed and tasselled corn stood tall and dense, rank behind rank in military alignment – a serried army lush and strong.

Man, what a hellhole Dixie is, huh? Following more along those lines, the description gets to the social life — the main topic of the book, naturally. It first describes the youths:

The life about the place was amazing. There were the busy children playing in groups, the boys of the family mingling with the little darkies as freely as any other young animals, and forming the associations which tempered slavery and made the relation one not to be understood save by those who saw it.

Obviously the children of the plantation owners and their slaves (usually termed “servants” back in the day) were born into unequal conditions. Still, it didn’t matter much to them at the time, and growing up together made them part of the same little community. Following that, the author goes into long detail about the daily rhythms of life and work. Everyone had a role. As he states later:

It has been assumed by the outside world that our people lived a life of idleness and ease, a kind of “hammock-swung,” “sherbet-sipping” existence, fanned by slaves, and, in their pride, served on bended knees. No conception could be further from the truth.

It wraps up with a discussion of the harvest, describing the way in which grain was gathered and cut down by hand.

Family members

Page begins by describing the mistress, the most important figure on the plantation. Typically she ran the business side of it, and had an excellent memory for keeping track of paperwork and useful objects:

Had the papers been the lost sibylline leaves instead of old receipts and bills, and had the parcels contained diamonds instead of long-dried melon-seed or old flints, now out of date but once ready to serve a useful purpose, they could not have been more sacredly guarded by the mistress.

That’s merely the beginning. Page after page, he waxes most eloquent about her organizational abilities, her tireless work, her care for sick slaves, and her saintly character.

Then the author describes the master of the estate. From his facial expression, voice, and overall bearing he displayed confidence, steadfastness, and loyalty. This seriousness goes back to his ancestors, who risked it all in the American Revolution and then built the young country from scratch:

He had inherited gravity from his father and grandfather. The latter had been a performer in the greatest work of modern times, with the shadow of the scaffold over him if he failed. The former had faced the weighty problems of the new government, with many unsolved questions ever to answer. He himself faced problems not less grave.

[6]

[6]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here [7].

To clarify, these new problems referred to the war fever that was brewing from radical abolitionist agitation, which sought to settle the slavery question violently. This led to the raid on Harpers Ferry by John Brown, a fanatical mattoid who had intended to ignite a race war to the death. By that time, a vast number of whites in the North had been propagandized into such an ethnomasochistic lather that they thought a big bloodbath would be wonderful. (Where were their fine scruples about bad optics, the perils of violent accelerationism, and all that?) It wasn’t too long before they got what they wanted:

Outside influences hostile to his interest were being brought to bear. Any movement must work him injury. He sought the only refuge that appeared. He fell back behind the Constitution that his fathers had helped to establish, and became a strict constructionist for Virginia and his rights. These things made him grave. He reflected much.

Then he discusses the master’s reading material:

His bookcases held the masters (in mellow Elzevirs and Lintots) who had been his father’s friends, and with whom he associated and communed more intimately than with his neighbors. Homer, Horace, Virgil, Ovid, Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden, Goldsmith, “Mr. Pope,” were his poets; Plutarch, Bacon, Burke, and Dr. Johnson [8] were his philosophers. He knew their teachings and tried to pattern himself on them.

Other contemporary accounts of rural Americans concur that they read the classics for entertainment — the type of books we get assigned in college, at least those of us lucky enough to get a decent education at one lately. Not uncommonly, they knew Latin and Greek as well. That’s something to consider if some TV show suggests that they were all a bunch of dumb rednecks.

As for the younger generation, the author recalled some of the guys as a work in progress. This is about the only place in the book that the praise isn’t wholehearted:

They possessed the faults and the virtues of young men of their kind and condition. They were given to self-indulgence; they were not broad in their limitations; they were apt to contemn what did not accord with their own established views (for their views were established before their mustaches); they were wasteful of time and energies beyond belief; they were addicted to the pursuit of pleasure. They exhibited the customary failings of their kind in a society of an aristocratic character. But they possessed in full measure the corresponding virtues. They were brave, they were generous, they were high-spirited. Indulgence in pleasure did not destroy them.

On the other hand, he had nothing but praise for the young ladies:

She was the incontestable proof of their gentility. In right of her blood (the beautiful Saxon, tempered by the influences of the genial Southern clime), she was exquisite, fine, beautiful; a creature of peach-blossom and snow; languid, delicate, saucy; now imperious, now melting, always bewitching. She was not versed in the ways of the world, but she had no need to be; she was better than that; she was well bred. She had not to learn to be a lady, because she was born one. Generations had given her that by heredity.

Page goes on for page after page singing the praises of Southern belles. His attitude toward them resembles that of a medieval troubadour.

Household servants

Then the author begins describing the slavery system on the plantation. Relatively little description is given to the field hands who did the cotton picking and other agricultural work, other than recollections of harvest time and seasonal festivities. Instead, the author concentrates on those who worked at the estate. It’s likely that these were the ones he knew best.

I’ll add a few things to his description. Those selected to be domestic servants were the most intelligent of the slaves. They ended up being the best educated and most refined. Because of this, they formed the upper class in the black community. I would imagine that after emancipation, they tended to be the ones who quickly thrived, quite unlike the ghetto masses who still don’t have their act together. However, “house negro” in recent times has become a sort of epithet denoting insufficient radicalism. It’s therefore rather ironic that prominent black luminaries and skintellectuals who accuse their allegedly wavering Volksgenossen of being “house negroes” are probably descended from actual house negroes.

Once again, the description opens with a matriarchal figure, in this case the Mammy:

There are certain other characters without mention of which no picture of the social life of the South would be complete: the old mammies and family servants about the house. These were important, and helped to make the life. The Mammy was the zealous, faithful, and efficient assistant of the mistress in all that pertained to the care and training of the children. Her authority was recognized in all that related to them directly or indirectly, second only to that of the Mistress and Master. She tended them, regulated them, disciplined them: having authority indeed in cases to administer correction; for her affection was undoubted.

So the Mammy served as a governess, and the white children deferred to her authority in loco parentis. Still, there’s much more to be said, including the following:

Her authority was, in a measure, recognized through life, for her devotion was unquestionable. The young masters and mistresses were her “children” long after they had children of their own. When they parted from her or met with her again after separation, they embraced her with the same affection as when in childhood she “led them smiling into sleep.” She was worthy of the affection. At all times she was their faithful ally and champion, excusing them, shielding them, petting them, aiding them, yet holding them up too to a certain high accountability. Her influence was always for good.

I’ll add that black ladies who were highly-respected governesses were hardly uncommon. It’s rather strange, then, that Wikipedia has a snippy article about the “Mammy stereotype” which says that they were merely fictional characters who comprised a grotesque racial stereotype, also hinting that they’d be class enemies if they actually existed. Now we’ve heard from Thomas Nelson Page, who actually knew some of them — a “white supreeeemist” who had nothing but praise and the kindest words for them.

The white children also habitually deferred to two other household servants. These included the typically stern majordomo, and the typically jolly chauffeur:

Next to her in importance and rank were the Butler and the Carriage-driver. These with the Mammy were the aristocrats of the family, who trained children in good manners and other exercises; and uncompromising aristocrats they were. The Butler was apt to be severe, and was feared; the Driver was genial and kindly, and was adored. I recall a butler, “Uncle Tom,” an austere gentleman, who was the terror of the juniors of the connection. One of the children, after watching him furtively as he moved about with grand air, when he had left the room and his footsteps had died away, crept over and asked her grandmother, his mistress, in an awed whisper, “Grandma, are you ‘fraid of Unc’ Tom?”

The Driver was the ally of the boys, the worshipper of the girls, and consequently had an ally in their mother, the mistress. As the head of the stable, he was an important personage. This comradeship was never forgotten; it lasted through life. The years might grow on him, his eyes might become dim; but he was left in command even when he was too feeble to hold the horses; and though he might no longer grasp the reins, he at least held the title, and to the end was always “the Driver of Mistiss’s carriage.”

The rest of the household servants included the following:

Other servants too there were with special places and privileges, — gardeners and “boys about the house,” comrades of the boys; and “own maids,” for each girl had her “own maid.” They all formed one great family in the social structure now passed away, a structure incredible by those who knew it not, and now, under new conditions, almost incredible by those who knew it best.

The social life formed of these elements combined was one of singular sweetness and freedom from vice. If it was not filled with excitement, it was replete with happiness and content. It is asserted that it was narrow. Perhaps it was. It was so sweet, so charming, that it is little wonder if it asked nothing more than to be let alone.

That last paragraph surely would be sufficient to give any modern skintellectual a case of the vapors.

The rest

[10]

[10]“But most of all, what I miss about Africa was trying to sleep in a grass hut while being eaten alive by tsetse flies.”

Nearly the entire second half of the book is about various aristocratic diversions such as horse racing, fox hunting, and square dancing, as well as the famous Southern hospitality. Additionally, there’s much description of holiday festivities enjoyed by both whites and blacks. All the gallantry and cheer is documented lovingly, much in the style of the rest of the book. Christmas was quite an occasion indeed; the reader will find out what they did to prepare and celebrate it in the days of yore before the customary trip to the mall on Black Friday. All this is of historical and cultural significance, so that the old times there are not forgotten. I’m painting this part with broad brushstrokes, however, as this is of secondary importance to our purposes here.

Nearing the end, the author begins a summation:

That the social life of the Old South had its faults I am far from denying. What civilization has not? But its virtues far outweighed them; its graces were never equalled. For all its faults, it was, I believe, the purest, sweetest life ever lived.

Then he names Dixie’s accomplishments, a long list which includes the following:

[I]t christianized the negro race in a little over two centuries, impressed upon it regard for order, and gave it the only civilization it has ever possessed since the dawn of history. It has maintained the supremacy of the Caucasian race, upon which all civilization seems now to depend.

Back in the day, the author could state the obvious with little danger that anyone would suffer a complete meltdown. These days, the above would make Leftists shriek like little girls at a slasher movie.

The battle of narratives

Social Life in Old Virginia Before the War does have some interesting surprises for modern readers. Generally, plantation life as described had some parallels with British feudalism. The book doesn’t explore that connection, though Southern planters sometimes saw themselves in that role.

[11]

[11]You can buy Fenek Solère’s novel Rising here [12]

It describes the masters and slaves as being on fairly cordial terms. The children even deferred to some of the domestic servants as authority figures. The author’s observations do agree with various others at the time which reported fairly congenial relations between the races, including a number of freedmen themselves. He didn’t mention any of the usual Uncle Tom’s Cabin litany of atrocities, and it’s entirely possible that nothing of the sort came to his attention during his boyhood. The furthest he went was to state in general that “the Old South had its faults,” just as any society does. Obviously, all this is wildly at odds with the present-day view of the plantation system as an unrelenting chamber of horrors.

He may indeed have been describing Dixie exactly as he saw it, but once more, this is a matter of perspective. Does the book portray the rose-tinted memories of youth as a charmed age, before a ghastly war and a brutal occupation? There might be something to that. More to the point, I can hear the question already: But what about the blacks? What did they think about this arrangement? Could there have been tensions that the slaves would have had reason not to discuss except among themselves? If some plantations were run like a benevolent dictatorship, surely there existed others that were despotic. There was, of course, abolitionist literature which presented a much different side. What was a plantation really like: happy darkies, or a torture chamber?

The true answer to the false dichotomy of “all slaves were contented” versus “all plantations were hell on earth” is that individual situations obviously differed. Note well that I have a strong dislike for the “mean value theorem of the truth” fallacy. When disputing someone who wildly exaggerates a story, I have little use for those who assume that I’m stretching things exactly as much, and that the real truth must be somewhere in the middle. Putting it another way, when someone claims that 2+2=4 and someone else claims that 2+2=6, it doesn’t follow that 2+2=5. That’s not what I’m going for here, and I hope not to give such an impression.

To be specific, it’s clear that some slaves in the antebellum South were treated decently and others were mistreated. To get a better understanding of that time and place, the proper question should then be: Which tended to be the more typical situation? To get a balanced picture, one would have to consult the words of the slaves themselves, and not only the ones who had such a bad experience of plantation life that they walked off and joined the abolitionist lecture circuit. Fortunately for historical interest, there exist a number of recorded descriptions by freedmen — but that’s another subject for another article.

That said, I certainly find Social Life in Old Virginia Before the War more credible than the gaggle of red-diaper baby activists pretending to be historians — looking right at you, Howard Zinn [13]. He and a number of other professional prevaricators spent their careers busily rewriting the past to make white people look bad, especially Americans, by gaslighting us about our past. The worst part of it is that their Marxist demoralization propaganda gets assigned to students under the guise of academic textbooks. One might argue that Thomas Nelson Page had his biases, too, but he also had the benefit of actually experiencing the Old South. Moreover, any one of this Southern gentleman’s fingernails alone contained more integrity than a dozen pinko professors like Comrade Zinn, who lie whenever their lips move.

[14]

[14]You can buy Greg Johnson’s It’s Okay to Be White here. [15]

Once again, what about the blacks? As it happens, the woeful tale of their woebegone woes has saturated the discourse for ages. It’s all about them now, and that’s no exaggeration [16]. Contrarian works about the Old South by Page and others who were actually there for the most part have disappeared down the memory hole. In their place, the popular image of that era is supplied by victimization porn such as the wildly popular Roots miniseries [17]. (It sure seems like someone in the entertainment industry wants to make white people look bad; golly, I wonder what’s up with that?) As incredible as it seems, even that 50-megaton white guilt bomb has been exceeded in sheer sadomasochism [18] lately with utter malarkey [19] about “buck breaking.”

Thomas Nelson Page didn’t suspect the half of what was to come when he wrote, “The most renowned picture of Southern life is one of it as it related exclusively to that institution.” Slavery is the biggest thing in America to harp on lately, and may be invoked to inject some ready-made demagoguery into a subject no matter how irrelevant [20]. (Of course, The Narrative conveniently forgets that it existed all around the world since the beginning of time — until white people abolished it.) Quite strangely, for the number one source of prefabricated white guilt, slavery has surpassed even The Holobunga itself. Could historical revisionism have taken some of the piss and vinegar out of the latter? Either way, surely this change in emphasis wouldn’t have happened if some influential people didn’t regard slavery as being more potent for pushing anti-white agitprop.

All told, slavery is inherently exploitative. Establishing it in colonial America, especially with an unassimilable race, was a tremendous mistake. On the other hand, there are those who constantly harp on the associated victimization porn in order to push their own agendas disingenuously. Whites need to be aware that collective guilt is not a valid concept, and that it’s being promoted to manipulate them. As for blacks, stories about the tribulations of their distant ancestors have been tremendously overhyped. Moreover, they should be aware that they too are being manipulated — and by the same manipulators.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[21]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[21]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.