Death by Hunger: Two Books About the Holodomor

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledAnne Applebaum

Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine

Great Britain: Penguin Books, 2017

Robert Conquest

The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror Famine

New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 1986

The [Communist] Party’s . . . rationale for everything done to the kulaks, is summarized with exceptional frankness in a novel published in Moscow in 1934: “Not one of them was guilty of anything, but they belonged to a class that was guilty of everything.” — Robert Conquest

Ukraine suffered a dreadful famine between 1932 and 1933. In a terrible irony, the famine took place in Europe’s most productive agricultural region. This famine was man-made, and it came to be called the Holodomor, which roughly means “death by hunger” in the Ukrainian language. The fallout from this disaster continues to drive the geopolitical narrative [2] in Eastern Europe today.

There are two excellent books about this deliberate famine: The Harvest of Sorrow (1986) by Robert Conquest [3], and Red Famine (2017) by Anne Applebaum. Conquest and Applebaum wrote about the same subject, but the two writers are not politically or ethnically similar. Conquest was a man of the Right, an Englishman whose father’s family is of old-stock American heritage [4]. He started writing about the Soviet Union in the late 1960s and was heavily criticized by the liberals of the day [5] for his anti-Soviet attitude. Conquest’s most famous observation [6] was that “[a]ny organization not explicitly Right-wing sooner or later becomes Left-wing.”

Anne Applebaum is a liberal Jewish woman who is married to a Polish diplomat [7]. She writes for The Atlantic [8]. Applebaum supported the unnecessary, Israel-first attack on Iraq in 2003, but she denies being a neoconservative. She almost always supports what the organized Jewish community likes, such as pardoning Roman Polanski [9]. Applebaum is a vigorous opponent of Russia and pushes for greater American involvement in Eastern Europe. While her actions are in line with the interests of the American Jewish community, the main thrust of her work is to advance Poland’s interests.

The reaction to their books in the mainstream is also different. When Conquest wrote about the Soviet Union and the Holodomor, he was seen as a reactionary and criticized for it. Applebaum’s book has not been criticized at all.

Conquest wrote during the Cold War. To use a rough categorization, heartland Americans and conservatives were anti-Soviet during the Cold War, while liberals — especially Jews in America — were soft on Soviet Communism, and were sometimes outright sympathetic. In more recent times, Jewish liberals such as Anne Applebaum tend to be viciously anti-Russian.

Of the two books, Conquest’s Harvest is the better read. Its main theme is systems; namely, Communist totalitarianism and its dysfunctional economic ideology. The clash between Ukrainians and Russians is a major secondary theme, however. Applebaum focuses on Ukrainian nationality, Ukraine’s place in Europe, and its dysfunctional relationship with Russia.

[10]

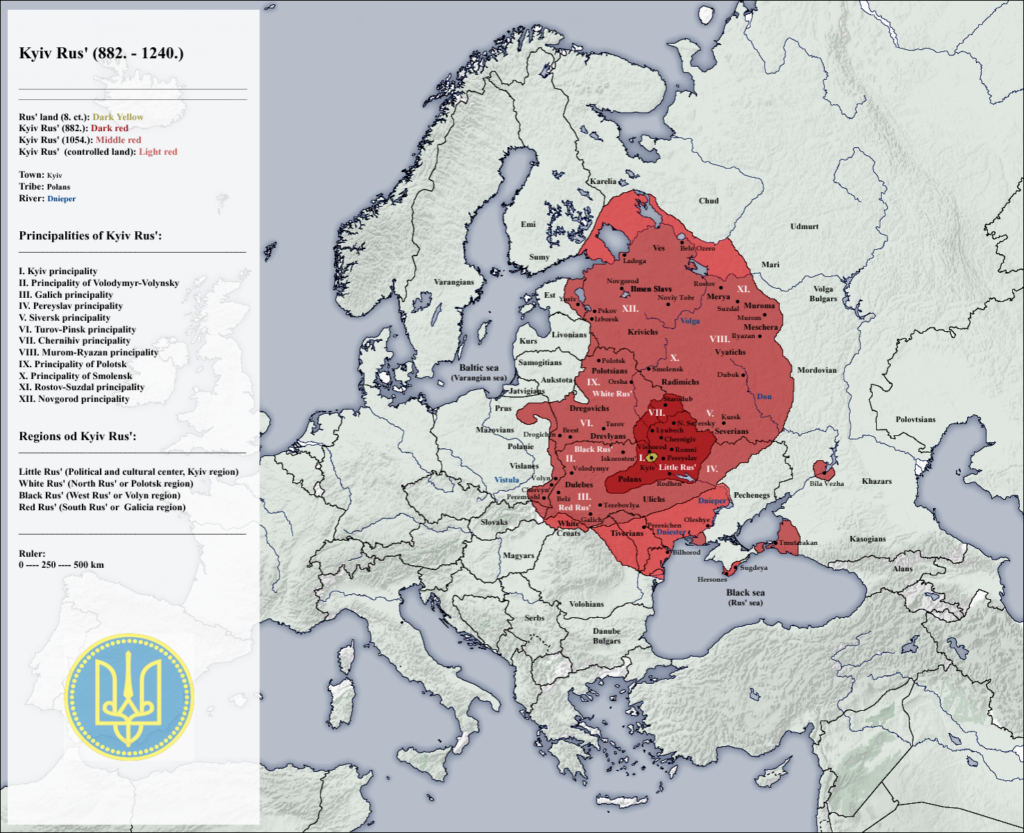

[10]The Russian and Ukrainian people and states originate in the Viking settlement of the Kievan Rus.

Ukraine and Russia have common origins in the Kievan Rus, a Middle Age polity which was set up by Vikings [11]. Lothrop [12] Stoddard [13] writes:

The legend of the founding of Kiev is quaintly significant. The story goes that the local tribes were so afflicted by domestic feuds and raids by their neighbors that they invited a famous Viking chief to be their ruler. Their invitation is said to have run as follows: “Our land is great and has everything in abundance, but it lacks order and justice. Come and take possession and rule over us.” Whether or not the legend states the exact facts of the case, certain it is that about a thousand years ago a Norse chief named Rurik did become ruler of Kiev and built up a state which soon became powerful and which laid the foundations of Russian nationality and civilization. It is also noteworthy that the early political centers in northern Russia, like Novgorod and Pskov, lay likewise on the Scandinavian trade-route [14] and seem to have been mainly due to Scandinavian influence.

The Viking influence on modern Ukraine is significant [15]. Ukrainians look like northern Europeans, and archeological evidence shows links between Viking Age Sweden and the Viking Rus. Christian missionaries converted the Viking rulers to the Greek Orthodox persuasion almost as soon as the Rus set up their own government.

The Mongols conquered Kiev [16] in 1240, destroying it completely. Although they didn’t settle in the region, they had a long-lasting negative impact regardless. Not only was the Kievan Rus’ political elite destroyed, but the region’s economy developed into a peasant society. Conquest writes:

The peasant’s position was, until 1861, that of a serf — one usual Russian word (rab) meaning in fact ‘slave’ — whom his landlord actually owned, subject to higher authority. This sounds like what prevailed in the West in the period often characterized as ‘feudal.’ But ‘feudalism’ is such a broad word that to apply it to Mediaeval England and 18th and 19th century Russia alike is to miss the major differences. In the first place, under Western ‘feudalism’ the serf had rights vis-à-vis the lord, and the lord vis-à-vis the King. In Russia, after Mongol times, the lower simply had obligations to the higher. (Conquest, p. 14)

The Mongol Empire was an economic and cultural disaster. Cities were flattened and cultures suppressed. The Mongols’ backwards Asiatic dominion was bound to unwind, and by 1480 they had been pushed back to their homeland. What is now western Ukraine then became part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which caused Ukraine’s national church to align with the Roman Catholic Church, although Orthodox liturgical practices continued. This alignment put western Ukraine in line with Western [17] Civilization [18].

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth declined in the eighteenth century, and was partitioned between Prussia, the Hapsburg Empire, and Russia by 1795. The Ukrainians became subjects of either the Hapsburg or Russian empires. The reason for these continuous shifts in who governed Ukraine is Ukraine’s geography:

Nikolai Gogol, a Ukrainian who wrote in Russian, once observed that the Dnieper River flows through the center of Ukraine and forms a basin. From there ‘the rivers all branch out from the center; not a single one of them flows along the border or serves as a natural border with neighboring nations.’ This fact had political consequences: ‘Had there been a natural border of mountains or sea on one side, the people who settled here would have carried on their political way of life and would have formed a separate nation.’ (Applebaum, p.1)

The Ukrainians were recognized by the Poles and Austrians as a different people with different traditions, and in the 1840s educated Ukrainians started to publish in their own language and to advance a particular national culture. The Russians didn’t see the Ukrainians as different from themselves, nor do they today. Then and now, Russians see Ukrainians as their wayward kin. When Tsarist Russia ruled Ukraine, the language of the cities in Ukraine was Russian, while the language of the country and villages was Ukrainian. The Ukrainian language was officially ignored — when not actively suppressed.

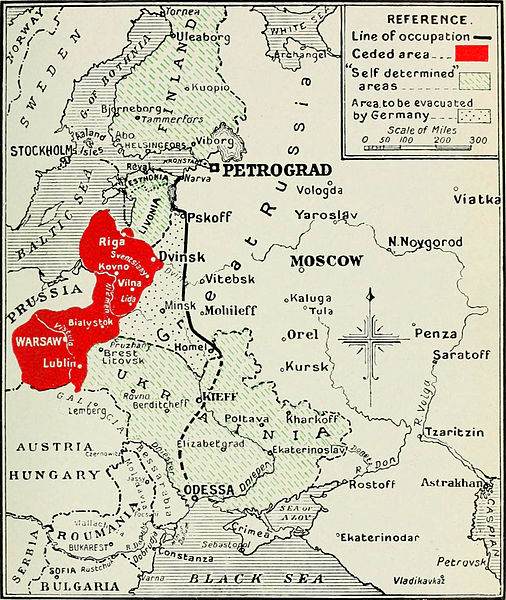

Then came the First World War. The war went so badly for the Russian Tsar that he was overthrown in the Russian Revolution. The Bolsheviks eventually captured the machinery of state that had been the Russian Empire. Ukraine briefly became independent in 1917 but was occupied by the Germans shortly thereafter. Then, when the German Empire collapsed in 1918, Ukraine became a battleground for various factions that were attempting to pick up the pieces. The great misfortune of the Ukrainian nationalists and their anti-Bolshevik “White [21]” allies in the former Russian Empire was that they were unable to unify. The better-organized Bolsheviks eventually triumphed in Ukraine in the early 1920s, after which they continued the Russian Empire’s policy of denying the existence of a separate Ukrainian people.

[22]

[22]The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed between the Bolsheviks and the Central Powers in early 1918. British and French propaganda framed the treaty as an illicit land grab by Prussia, but when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, its western portions broke away along the same lines as Brest-Litovsk.

Two major events happened at this time that set the stage for the Holodomor. The first was that the anti-Bolsheviks used Ukraine as a base from which they could organize a strike against the Bolshevik government in Moscow. A White Russian Army that started out from Ukraine almost captured Moscow in 1919 [23]. This near miss showed the Bolsheviks that Ukraine was dangerous to them. The second was that they realized that if their regime was to survive, they had to feed the people in Russia, as the latter had been thrown into poverty and starvation during the Civil War. They did so by robbing Peter to pay Paul, with Ukraine as the one getting robbed.

[24]

[24]You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s Solzhenitsyn and the Right here [25].

Bolshevik officials scoured Ukraine for grain, robbing farmers at gunpoint. The resulting disorder cut into food stocks and lowered agricultural production in Ukraine, and famine followed in the early 1920s. One Russian-German [26] settler in Ukraine, Ben [27] Klassen [28], was caught up in these events and fled with his family to Canada when he was a small boy. He would later move to the United States, prosper, and become a white advocate [29].

The Bolsheviks believed in Marxist economic theory with a religious fervor, which has its roots in the French Revolution’s Jacobin Left [30]. Karl Marx and Frederick Engels [31] further developed these ideas into a political and economic theory in which society would be remade so that capitalists, landowners, bankers, and businessmen would be replaced by a state-run economic system that would distribute all resources to everyone equally: each according to his ability, and to each according to his needs.

Communism developed out of Marxism, and by the early twentieth century many were swept up into supporting it with a religious fervor. Communism’s power came from its status as a quasi-religion. It is a Christian heresy [32] that promises a future in which the lion lies down with the lamb, and a theology expressed in materialistic terms. The “meek” – i.e., the industrial workers — will inherit the Earth. Private property, trade, and economic innovation are to be suppressed so that an economic utopia can be achieved.

The famine in Ukraine in the early 1920s created considerable resistance to the Soviet government. Ukrainian peasant women organized and participated in riots. The men refused to work. Eventually, the Soviets backed down. The peasants returned to their farms and production resumed.

Their resistance had come as a shock to Moscow, however. Marxist theory had little to say about peasants other than that they didn’t have a “class consciousness.” Furthermore, the Communists had no sympathy for Ukrainian nationalism. To control the peasants and repress Ukrainian national ambitions, the Communists invented social classes among the Ukrainian peasants and set them against each other. These completely new classes were kulaks (“wealthy” peasants), seredniaks (middle class peasants), and bedniaks (poor peasants). In Ukrainian, kulak literally means “fists.” Applebaum writes:

The term had been rare in Ukrainian villages before the revolution; if used at all, it simply implied someone who was doing well, or someone who could afford to hire others to work, but not necessary someone wealthy. (Applebaum, p. 36)

Kulaks included peasants who leant money to others. While this may appear to be a good definition, the truth is that the exact rules of who was a kulak and who wasn’t was ill-defined, and deliberately so. In practice it meant any Ukrainian from a rural background who the Communist officials didn’t like. One could become a kulak very quickly, and there was no way to undo it.

The Communists blamed the kulaks for everything going wrong. The Holodomor was proceeded by a decade of anti-kulak hate rhetoric. This was an ethnic conflict, but it was not as simple as Russians — or even Jews [34] — versus the Ukrainians, although Jews, especially those outside the old Russian Empire, had supported the Bolshevik Revolution and were sympathetic to the Soviet Union. The early Soviet government was made up of minorities from across the old Russian Empire: Jews, Georgians, and others [35], although there were ethnic Russian Communists as well. They aligned against another ethnic group, the Ukrainians, which had a national consciousness but was poorly organized and had not yet achieved the ability to effectively govern and defend itself before being occupied by its multicultural imperial rival.

Conquest says less about Joseph Stalin, the Soviet Union’s second leader, than Applebaum. Stalin’s leadership was critical in creating the conditions for the Holodomor. Stalin, born in 1878 as Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili, was a Georgian [36]. He briefly studied to be an Orthodox priest, but soon changed his religion to Communism. He robbed banks in the name of the revolution and wrote articles. He was appointed the Communist Party’s General Secretary in 1922, a position the duties of which were then ill-defined. From there he built a loyal security force that aided his advance to absolute power via one-sided show trials against his Bolshevik rivals and outright killings.

When the Bolsheviks were clamoring for grain shipments to Moscow and Petrograd to keep their dismal revolution on track in 1918, Stalin was sent to the city of Tsaritsyn, on the Volga River, to procure food. Stalin used the secret police and Red Army troops to kill or imprison any rival, and then swept the region for grain and shipped it northwards. Stalin’s brutal tactics got him removed, but he had achieved a proof-of-concept exercise in achieving and wielding power as well as subjecting a population to his control. When Stalin eventually came to absolute power over the USSR, he renamed Tsaritsyn Stalingrad and implemented the same methods he had pioneered there in Ukraine.

In 1929-30, Stalin made his move to crush Ukraine. Conquest writes,

Academician Sakharov [37] writes of ‘the Ukrainophobia characteristic of Stalin’; but it was not, from a Communist point of view, an irrational Ukrainophobia. A great nation lay under Communist control. But not only was its population unreconciled to the system: it was also true that the representatives of the national culture, and even many Communists, only accepted Moscow’s rule conditionally. This was, from the Party’s point of view, both deplorable in itself and pregnant with danger for the future. (Conquest, p. 217)

Stalin had Ukrainian intellectuals arrested and tried from March 9 to April 20, 1930: scholars, critics, writers, linguists, students, and lawyers, as well as former political figures from extinct Ukrainian political parties. This assault on the Ukrainian intelligentsia was the harbinger for the broader attack on the “kulaks,” which eventually expanded to become an attack on all Ukrainians in the countryside. The Soviet government was especially hostile to Ukrainian Protestants; for some reason they considered Baptists [38] a major security threat.

Just before Ukraine’s own leadership was herded to the gulags or the gallows, the Soviets created a cadre of non-kulak security forces there to carry out their will. Any peasant who had taken the initiative to better himself was a kulak. This meant that an unemployed drunk or a borderline criminal was automatically considered anti-kulak. These men were recruited into Ukraine’s Stalinist internal security force. These recruits understood that had come to their positions unnaturally and that they were in a war to the death with their more productive neighbors. The security forces were aided by true-believing Communists in the secret police as well as the well-armed and well-fed Red Army. The Ukrainians themselves had already been disarmed throughout the previous decade by various means, and were thus defenseless.

The Soviet Politburo decreed in July 1930 that 70% of households in the main wheat-growing regions — especially in Ukraine — were to join collective farms by September 1931. The Soviets recognized that to achieve this goal, they would require “the liquidation of the kulaks as a class.” They did this through several policies adopted at once. Private Ukrainian farmers were excessively taxed. The Soviet security forces seized grain supplies from the farms, even including chicken feed and whatever food the famers had in the pantries for their own consumption. As with the earlier famine, this oppression suppressed agricultural production, and soon there was no food in the rural areas at all. The farmers were then forced to give up their land and move to the collective farms

The first signs of mass starvation appeared in secret police reports in the early 1930s. The Soviet government continued to double down on its food seizure policies regardless, and stopped any Ukrainian from leaving the area where he lived. By the autumn of 1932, the ordinary signs of harvest time — pumpkins for sale, hay bales, and vodka distilling — were absent. The peasants were instead boiling ground-up bones or shoe leather, eating dogs and cats, and digging with their bare hands in the snow for acorns.

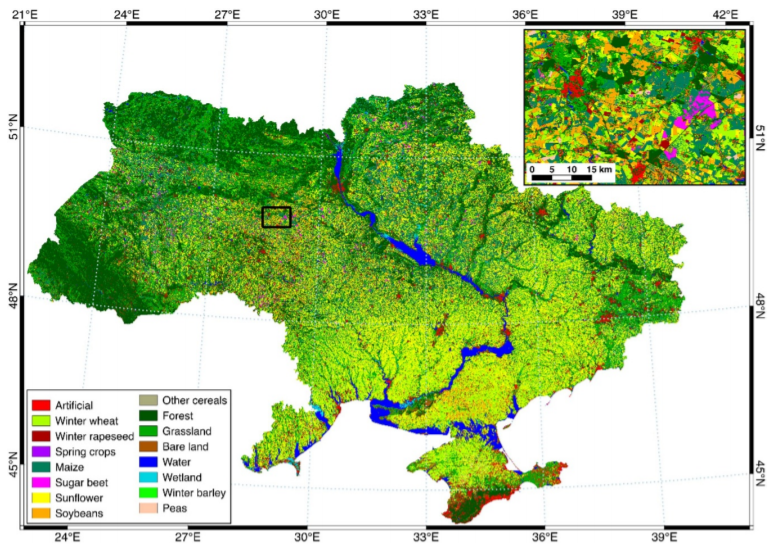

[39]

[39]Ukraine’s agricultural areas. The Soviet government was keen on collectivizing Ukrainians in the wheat belt.

If a peasant had relatives abroad, it was possible to get some help, but not much. Peasants who still had Tsarist gold coins or jewelry could at least buy food. In some areas, Ukrainians dug up the graves of old aristocrats who’d been buried with their jewelry. This was risky, however, as Ukrainian society at this time was lawless, and travelers bearing gold were often waylaid.

[40]

[40]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Toward a New Nationalism here [41]

Russian speakers in the towns made out better. They were given ration cards to buy food, although not much. Party officials were able to get more food and goods than others by using special ration cards and shopping at special stores.

The Soviet Union’s violent first three decades were curious in that the Bolsheviks worked to uproot and destroy Russian culture in the national centers of Moscow and Leningrad while being pro-Russian in other places. During the Holodomor, the assault on Ukrainian culture went beyond arresting the elite and starving the peasants. In many areas the empty villages were filled with Russians. Ukrainians were deliberately replaced with Russians in Kuban [42], for example. In Kazakhstan [43] Soviet policies led to a similar famine as in Ukraine, and the region was likewise Russified. In both places the Russification didn’t take very well, however, as the Russian settlers didn’t adapt to the Ukrainian and Kazakh steppes very well, and many of them returned to their home towns.

Stalin’s government hid the scale of the famine as best as possible. The Soviet media created an alternate reality of happy collective farms and smiling, well-fed people. Foreign visitors to Ukraine were sent to locations where there was no famine, and were furthermore carefully selected for compliance to Soviet dogma. When the USSR conducted a census in the late 1930s and it was clear that the famine had taken the lives of millions, the results were hidden and those in charge of the census were shot.

The American and British mainstream media was as partisan and dishonest during the Holodomor as it is now. Some journalists, including Malcolm Muggeridge and Gareth Jones, did go to Ukraine and honestly report on conditions, but others either self-censored or were otherwise sympathetic to the Communists [44]. Many newspaper editors in the United States or Britain removed references to starvation from articles, and there were even rewards for reporters who were biased towards the Soviet Union. Applebaum writes:

Extra rewards were available to those who played the game [of lying about the Soviet conditions] particularly well, as the case of Walter Duranty famously illustrates. Duranty was the correspondent for The New York Times in Moscow between 1922 and 1936, a role that, for a time, made him relatively rich and famous. Duranty, British by birth, had no ties to the ideological left, adopting rather the position of a hard-headed and skeptical ‘realist’ trying to listen to both sides of a story. ‘It may be objected that the vivisection of living animals is a sad and dreadful thing, and it is true that the lot of kulaks and others who have opposed the Soviet experiment is not a happy one,’ he wrote in 1935. ‘But in both cases, the suffering inflicted is done with a noble purpose.’ (Applebaum, p. 316)

The Communists eased off their policy of starving Ukraine to death in early 1933. Neither Conquest nor Applebaum say why the Soviets did this. It seems there aren’t any known documents from Stalin’s inner circle that shed light on why they chose to end the famine. But for whatever reason the repressive policies were eased and the famine ended as peasants were able to return to work. Ukrainian society had been badly damaged, however. It is indeed possible that the corruption and distrust of the government that we see in Ukraine today goes back to the famine, when government officials were the agents of a foreign, multicultural empire carrying out a genocide.

The Holodomor was partially the result of an inefficient economic system. Communist economic theory simply didn’t work. The collective farms stumbled along throughout the entire history of the Soviet Union, barely feeding anyone. Herds of cows perished as a result of bad feed, farm workers made a minimum effort to bring the harvest in, and morale was low. The small, private farms that survived the push for collectivization ended up supplying much of the USSR’s food.

The main reason the Holodomor occurred, however, was that it was an ethnic conflict between a vast, multicultural empire and a national culture that was just starting to find its own way in the world. At every point during the Holodomor the Soviet government made a point of deporting, imprisoning, murdering, or suppressing Ukrainians — even Ukrainian Communist Party members.

Anti-Ukrainian policies continued in the USSR even after the Holodomor, although never to the same degree. Conquest writes:

In the period 1945-56 Ukrainians constituted a very high proportion of labor camp inmates, and are invariably reported as the most ‘difficult’ prisoners from the police point of view. Their death roll, especially in the worst camps where they were most often sent, was very high. In the 1950s in the fearful arctic camps of Kolyma [45], girl villagers who had supported the rebels were to be found. A Polish prisoner unsympathetic to Ukrainian nationalism nevertheless noted, ‘But why had Soviet officers, interrogating seventeen year old girls, broken the girls’ collar-bones and kicked in their ribs with heavy military boots, so that they lay spitting blood in the prison hospitals of Kolyma? Certainly such treatment had not convinced any of them that what they had done was evil. They died with tin medallions of the Virgin on their shattered chests, and with hatred in their eyes.’ (Conquest, p. 334)

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [46]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[47]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[47]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.