Believing and Knowing: Ethnonationalism and Religion

Posted By John Morgan On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled [1]

[1]The only genuine traditional form of society: one ruled by a nobility that is guided by a priesthood.

3,770 words

The following is the text of a talk that was given at the recent Counter-Currents Spring Retreat. The video can be seen here [2], or below.

Cyan asked me to speak on this topic, and before I begin, I just want to clarify something, because when it comes to these matters I’m overly pedantic. But historically speaking, ethnonationalism and religion don’t go together. This is because the nation-state itself, which was born out of either the French Revolution or the Second English Civil War, depending on who you ask, has always been secular and opposed to any mixing of politics and religion. According to the doctrines of Tradition, as explicated by René Guénon and Julius Evola, among others, the only valid form of government is a monarchy that is anointed by and is guided by a priesthood. I was taught the same thing when I practiced Hinduism in India as well, and it’s likewise what is taught by every one of the world’s major religions, so this isn’t something that is limited to obscure philosophers.

This was in fact the form of government that existed everywhere in the world for all of recorded history until the English, French, and American revolutions. Nation-states have always sought to sideline or even eradicate religion altogether — sometimes extremely violently, as in the case of the French Revolution.

Moreover, ethnonationalism — which is rather redundant as a term, as until the recent rise of civic nationalism all nationalisms were based in ethnicity — has always been used by liberals as an instrument to destroy traditional political forms based on religion, such as kingdoms and empires. European liberals in the nineteenth century always saw themselves as being at war with monarchs and emperors on behalf of the common people of a specific ethnicity with the aim of establishing nation-states. A prime example of this is the 1848 Revolution in Hungary, which was the most dramatic and longest lasting of the revolutions that broke out in that year, and where the Hungarians fought the Hapsburgs in an attempt to break away from the Austrian Empire and establish a nation-state. They were defeated — although few Hungarians would argue that the period of the dual monarchy, or the Austro-Hungarian Empire, that followed was the high point of Hungarian history in the last 500 years. And in fact many Hungarians on the Right today see the 1848 Revolution as having been a mistake.

The victorious Allies in the First World War similarly used ethnonationalism as a pretext to break up the German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman empires, and much of the violence that has plagued the world in the hundred years since can be traced back to the vacuum that was created by their fall and the attempt to reorganize peoples who had previously (mostly) coexisted peacefully in empires and kingdoms into nation-states based on ethnicity. And of course today we see liberals in Europe and the United States using ethnonationalism in Ukraine in an attempt to break up Russia — which, while no longer an empire in the traditional sense, the Russian Federation could be seen as a sort of pseudo-empire that has inherited the legacy of the Russian Empire. Thus, the track record of using ethnonationalism for what were traditionally Right-wing aims, if we understand the Right in the same sense that it was used when the term was first coined during the French Revolution, isn’t good.

But, since absolute monarchy is unlikely to make a comeback anytime soon, for the sake of today’s discussion, let’s say that a future ethnonationalism could be something of the Right — and there’s no reason it couldn’t be, if the concept of the nation-state that prevails today were altered. And the only possibility for achieving ethnonationalism today, unfortunately, is through electoral politics.

I titled this talk “Believing and Knowing” after something that the Swiss psychologist and philosopher[1] [3] Carl Jung said in an English-language film interview he gave to the BBC in 1959. You can watch it on YouTube [4]. Jung was asked if he believed in God. Jung looks nonplussed for a moment, and then he says, “I don’t need to believe, I know [5].”

It seems to me that this is the essence of the distinction between the traditional and the modern worldviews, and by extension the difference between looking at religion from the modern political viewpoint as opposed to a personal viewpoint. I’m therefore going to address these two issues separately in this talk: religion and ethnonationalism, and religion and the ethnonationalist.

When it comes to religion and politics, my short answer to the question of how they should be combined at the present time is that they shouldn’t be. In relation to ethnonationalism, it might be sensible to make use of religious identity in places where the majority still identify with a specific religion, such as in some of the countries in Eastern Europe. Although even there, I’ve noticed that those populist parties which appeal to Christianity do so only in a very vague way, referring to rather bland conceptions of values and a sense of community in a way that would have been regarded as quite milquetoast only a century ago. But you won’t find even Right-wing politicians in Hungary calling for the posting of the Ten Commandments in schools, or doing away with the teaching of evolution, as in the United States. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán once commented that he wasn’t seeking to impose Christian morality or theology on Hungary, but rather to defend those values which had their origin in Christianity but then evolved into particular social principles in Europe, such as equality between men and women (the example he has cited on occasion).

[6]

[6]You can buy Julius Evola’s East & West here [7].

But when it comes to Western Europe and the United States, it seems to me that religion in politics can only be a divisive issue — firstly because no one could agree on which particular religion among the plethora currently being practiced in those countries should be pushed, and second because in Western Europe in particular the vast majority of people identify as secular — or at the very least only see themselves as belonging to a particular religious community, but which otherwise has little effect on how they live their lives. The statistics show that this is increasingly the case in the US and Eastern Europe as well.

Poland, for example, which 30 years ago was seen as a bastion of traditional Catholicism, today seems to be going the way of Ireland, and more and more people under 40 want to model themselves and their country on the West’s secularism. (The reasons for this can be debated, but from what I have seen and read, many conservative Poles attribute this to the influence of social media.) The ruling Law and Justice Party, which makes very explicit appeals to Catholic doctrine on issues such as abortion, remains very popular with older Poles, but as more and more younger people become voters, its power has been decreasing. Today it seems to be hanging by a thread and will likely have to go into a coalition if it is to have any chance of retaining power after the election later this year.

Such “Christian nationalism” hasn’t fared much better in the US, either. The Republicans chose to make Christian nationalism a focus of their appeal during the last midterm elections, but it doesn’t seem to have had much of an impact on the voters given that the much-anticipated “red wave” failed to happen. Perhaps it’s because ordinary Americans were more interested in hearing about what the Republicans might do about inflation than being told that the problem with government is that it needs to embrace “Christian values.”

Thus, I don’t see what can be gained from making religion a focus of ethnonationalist or any other form of political activism in the West at present. I even attended an event a few years ago [8] at which representatives of various Christian democratic parties from around Europe spoke, many of the latter of which remain quite prominent in their respective countries. The one thing that nearly all of them agreed on at this event was that Christian democracy as a concept is now a misnomer, since few Europeans today vote in terms of Christian values. You can’t have Christian democracy when there aren’t any Christians, as one of them pointed out.

So if societies all over the West are becoming increasingly secular [9], why do allegedly Right-wing parties keep appealing to religion? The answer is clear: When you don’t dare to ever mention race or ethnicity because you are afraid of being called a Nazi, a universalist religion such as modern Christianity is one of the few things you can call upon as a basis for your rhetoric. (Economics is essentially the only other one.) Religion then becomes a surrogate for ethnicity. This may still work to a certain extent in countries such as Hungary and Poland, which are still largely ethnically homogeneous and where the majority of the population identifies with a single faith.

Although even there, it still leads to problems. Many prominent so-called “conservatives” fervently believe that Christianity, or at least the versions of it that prevail today, should override all other concerns. They believe this so fervently, in fact, that it leads to situations such as one that F. Roger Devlin wrote about in an article that we ran at Counter-Currents recently [10], where the American “Christian conservative” guru Rod Dreher arranged for the firing of a headmaster of a private school in Louisiana where Classical Christian Education is taught named Thomas Achord. Achord had previously been doxed after it was discovered that he had published some politically incorrect remarks about race under a pseudonym. Dreher blasted him for being a “vile racist,” among other things — and this wasn’t just any school, but was one where Dreher had sent his own children. Achord, who has a family of his own, lost his job as a result, and has had to resort to crowdfunding [11] just to make ends meet. This again brings us back to Hungary, since Dreher is currently living in Budapest as a guest of Viktor Orbán’s party, Fidesz, and has become the linchpin of a group of American and Western European conservative intellectuals Orbán has brought in to bolster his own metapolitical efforts. Dreher even has private meetings with Orbán on occasion. The only conclusion to be drawn from this is that Christian conservatism today has the same view of those who stand up for their own racial and ethnic interests as the liberal Left does.

Further, populist Right-wing parties in Europe, just as the American Republicans, commonly refer to “Judeo-Christianity” today, and love to talk about the absurd idea that modern European civilization is the product of both Athens and Jerusalem. (In fact, ancient Athens and Jerusalem were in conflict, but that’s beyond the scope of this talk.) Judeo-Christianity [12] is actually an American invention of the twentieth century that was coined during the Cold War. Certainly few Christians prior to the mid-twentieth century would ever have thought that their religion and Judaism were a common faith – especially as the Christian churches, not to mention Jesus himself, were often at odds with Jewry historically. Today, however, their unity is regarded as self-evident and sacrosanct — obviously because it’s a useful way for conservatives to deflect charges of anti-Semitism. In fact, Right-wing populist parties across the West today are universally philo-Semitic, despite the fact that they get little in return for their love apart from donations and an alibi to prove they’re not Nazis. Although such parties, of course, are obliged to continually reiterate their support for Israel as well as for Jewish groups in their own countries that, in many cases, don’t wish them well to begin them.

Putting this issue aside, however, we are then confronted by the fact that “Christian nationalism” inevitably leads to civic nationalism. Viktor Orbán, for example, is seen as a hardliner on illegal immigration around the world. But during a meeting with some American “conservative” Christian intellectuals, including Rod Dreher, last summer following his infamous “race-mixing” comment [13], he told those present that he has great hope for the future of the US — because of immigration from Mexico [14]. He’s obviously bought into the idea — or at least claims to — that Mexicans, and Latin Americans more generally, bring Catholic values with them when they come to the US, and thus magically make America more conservative. Although we’ve run articles at Counter-Currents in the past [15] which show that this idea is nonsense.

And even at home, Orbán’s party, Fidesz, makes the mistake of reiterating the conservative canard that somehow immigrants from the Third World who are Christian are somehow preferable to Muslim or other forms of migrants. This manifests, among other ways, as Hungary sending aid to Christians in Third World countries [16] in the belief that Hungarians — many of whom, being in a post-Communist country, are in need of aid themselves — somehow have an obligation to their Christian “brethren” overseas. But looked at from the perspective of the realities of race and ethnicity, this is a rather ridiculous assertion. (Although to be fair, I’ve spoken to Fidesz supporters who point out that it’s better to help the peoples of the Third World in their own countries so that they have less reason to want to emigrate, which I suppose is a reasonable assertion when the governments of the West are clearly unwilling to seriously pursue simply keeping these people out entirely.)

As an aside, I also want to mention that it’s highly questionable how committed today’s Right-wing populist parties are to their own anti-immigration rhetoric. A friend of mine who is a conservative journalist in Hungary has told me that, if you look at the numbers, legal migration into Hungary at present from outside the European Union is today per capita the same as in France. After all, Orban has only ever warned about illegal migration, but never talks about legal migration, which of course is just as much of a problem.

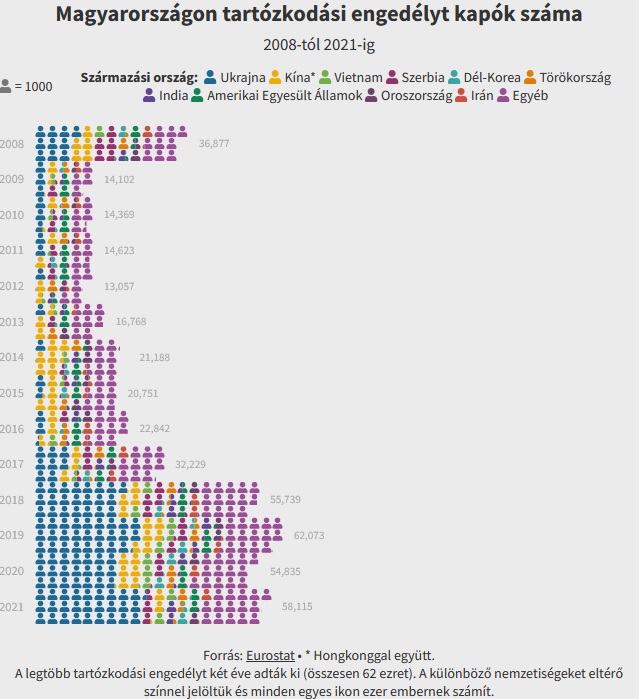

[17]

[17]A chart showing the number of residence permits issued in Hungary from 2008 to 2021. In 2021, 58,115 permits were issued (Hungary has a population of 9.7 million). Of these, 27,447 were issued to Ukrainian citizens (of whom a certain number, not specified in the statistics, are ethnic Hungarians). The rest includes 2,313 Serbs (also including a certain number of ethnic Hungarians), 2,067 Chinese, 2,035 Vietnamese, 1,837 Indians, 1,820 Turks, 1,671 South Koreans, 1,463 Americans, 1,183 Russians, and 1,026 Iranians, leaving 15,253 from other non-EU countries. Two-thirds of these are work permits, one-sixth are student permits, 7.5% for family reunification, and 9% for other reasons.

Moreover, Fidesz is currently debating a bill that would make it easier for the multinational corporations that operate in Hungary — the German auto industry is one of the main pillars of the Hungarian economy — to bring in workers from the Third World. This was recently exposed in an article by a Left-wing journalist in Hungary [18], ironically. It’s unclear how this will play out, but given that Fidesz has a supermajority in the Hungarian parliament, if they want this to pass, it will. (NOTE: Since I gave this talk, the bill was voted on and passed on June 13 [19].) But am sure that if it does, we will be told that all is well and good, since the migrants will be alleged to be coming from non-Islamic countries or some such similar “Christian nationalist” rhetoric.

I don’t want to deny that parties such as Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz or Poland’s Law and Justice party have done some good things for their peoples, and that they are far preferable to their Left-liberal opposition. But it’s important to recognize that what they’re offering is inadequate — not only from an ethnonationalist standpoint, but in terms of making any fundamental changes in the current catastrophic state and direction of our civilization.

So that’s all that religion can be in an age dominated by secularism and liberalism: a belief, that can perhaps be called upon when needed to make a political position sound more profound than it actually is, but that needs to be kept in its place and shouldn’t ever be taken seriously. We’ve seen the belief side. Now what about knowing religion?

For anyone who is serious about religion today, it has become very much an individual affair. I don’t want to preach to anyone, as I’m sure there are many different views about religion among those of us here today, but I think anyone on the Right needs to at least explore a traditional religion in order to have a complete grasp on what it is that we are fighting for. Religion at its best can provide one with a foundation for one’s beliefs in general — the idea that there is more to life than simply the material, which is the basis of the liberal worldview — as well as a firm beacon in one’s own life. For me personally, it has certainly served as an antidote to the rampant nihilism that surrounds us, and can be a strong reassurance and motivator when things are tough. I spent the better part of three years at a traditional ashram in India, and it was astounding to me how energetic and motivated everyone was to achieve goals in the real world as a result of the strength of their faith. Some of them pushed themselves to the absolute limits when it came to setting up real-world communities and pursuing other forms of activism. They do this not because they merely believe, but because they know that God is guiding them in their actions.

Knowing the truth of religion is something that can only be achieved through practice. The door to religion can be opened by the intellect, such as by reading and studying, but to really experience the truth of it directly demands that one experience it through dedicated practice over a long period of time; just as any other activity, it demands sacrifice and discipline. I won’t suggest any particular religion, as that’s very much a matter of one’s own “personal equation,” as Julius Evola put it. And of course the notion of “choosing a religion” itself is a modern notion. Before the twentieth century, the vast majority of people everywhere were simply born into a religion, and the notion of taking up any other, or of disbelieving altogether, seemed absurd.

[20]

[20]You can buy Collin Cleary’s Summoning the Gods here [21].

The notion of joining a religious community is dead for most of us today, since even those religious communities that still exist in the West don’t really adhere to their own principles any longer. Thus, true religion is something that each person has to discover on his own. Perhaps in one sense this is a strength, however, given that we are free to find our own path to the Holy Grail, as it were, rather than simply mouthing pieties that we are taught by rote.

I will therefore here plug for what is sometimes referred to as “Traditionalism,” which are the teachings explicated most notably by René Guénon [22] and Julius Evola [23]. (And of course, I should mention Counter-Currents’ own master of philosophical and religious topics, Collin Cleary [24], who is one of the best writers we have on these issues.) These names have been bandied about a lot on the Right in recent years, not least by Steve Bannon [25] (albeit his understanding of Tradition is extremely unorthodox), but few people actually read, and even fewer genuinely understand, what it is that they are teaching.

It is important to point out that, while it has profound political implications, Tradition is first and foremost a path for self-realization, not a political ideology. But we can’t change the world before we change ourselves, at any rate. And I think that the Traditional authors, while certainly not perfect, are unmatched for transforming one’s worldview at the most fundamental level and to point one towards knowing rather than merely believing. Tradition is the exact opposite of the liberal worldview in every respect, and once you accept its tenets, you’ll never be the same again. I speak from experience.

Once you achieve the insights brought by practicing a Traditional religion, the political viewpoint will follow. Evola very adamantly insisted that Tradition cannot be reduced to a program for a political party in a modern liberal state.

As an aside, we can again turn to Hungary to find an attempt to combine Tradition with party politics. The former leader of the formerly radical Right-wing party Jobbik in Hungary, Gábor Vona, dallied with Tradition for a few years and even appointed one of Hungary’s most prominent Traditional philosophers, Tibor Baranyi, to be his chief advisor. But the end result wasn’t good, as it had little concrete impact on Jobbik’s policies apart from causing Vona to make comments [26] about “Islam as the best hope for humanity” and such things, which only sounded strange to ordinary people. Vona abandoned Tradition after a few years, then the Traditionalists in Hungary abandoned Jobbik — and since then Jobbik has managed to transform itself into a Left-liberal party [27]. So let that stand as a warning.

Evola did not want to see a political party that espouses Tradition. What Evola called for was the establishment of an Order dedicated to Traditional principles that could guide a political elite from behind the scenes. It’s often said that Evola advised people not to go into politics, which isn’t strictly correct; he merely thought that those who adhere to the Traditional worldview and who go into politics should resist the temptation to become populists and instead remain guided by the higher and eternal values of Tradition. He actually wrote a short essay outlining the principles such an Order should have for his students called “The Order of the Iron Wreath [28].”

In closing, I urge you not merely to believe in, but to know what it is that you’re doing. The cause that we all share to one extent or another is not up for debate. We are all here not because we believe, but because we know that the goals we are pursuing are right and true.

Thank you.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [29]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[30]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[30]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Note

[1] [31] As James J. O’Meara pointed out to me, it is important to note that Jung himself emphatically denied that he was a philosopher, instead preferring to see himself as a scientist. Many have referred to him as a philosopher in spite of this, and it cannot be denied that Jung’s thought has had an enormous impact on not only psychiatry but also literature, art, myth, religion, philosophy, and many other areas of thought. Thus, to merely refer to him as a psychiatrist seems reductive.