Pretty Village, Pretty Flame: A Film for Understanding the War in Ukraine

Posted By Nicholas R. Jeelvy On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledAs I write these words, war rages in the Ukraine. Once again, white people are at each other’s throats in a bloody and brutal brother war. Much will be written about it. More will be said. Much of what is written and said will be false, loaded, unexamined, unkind, uncouth, and unfeeling. We will be unpacking this war for years, if it does not escalate into something that’ll kill us all. So while we’re all still around, I want to direct you to one of Europe’s past bloody brother wars.

The Yugoslav Wars were an orgy of violence and horror, not merely because of their intensity but even more so because the men who were killing each other, burning each other’s villages, and committing atrocities had been friends and neighbors only a few years earlier. I’ve heard from oldsters who took part (or who stood by as it happened) that it was surreal. Nowhere is the conflict’s surreal nature better portrayed than in Srdjan Dragojević’s film Pretty Village, Pretty Flame [2].

This film concerns a squad of Serbian soldiers who are cornered in an abandoned and reputedly haunted tunnel by the Bosnian army. As they run out of water and are killed one by one, they struggle to stay alive and sane. Its atmosphere of claustrophobic dread would make Hitchcock and Lovecraft proud. The Serbian squad is trapped between the Bosniaks outside the tunnel and the purported drekavac [3] which haunts the tunnel. But the drekavac is not the only spirit haunting the tunnel. The spirit of “the country which no longer exists” — of Yugoslavia and its Marshal, Josip Broz Tito — hangs over the whole film. But what interests me is the colorful cast of characters that comprises the Serbian squad.

I’ve often said that the Serb soldiers trapped in the tunnel represent every stereotype about Serbs in the 1990s gathered in one place. The squad is commanded by Gvozden (meaning Made of Iron), an old-school officer from the Yugoslav National Army, still enamored of his beloved Marshal Tito, having walked 350 kilometers in 1980 to pay his respects at Tito’s funeral. He is a no-nonsense, by-the-book officer stuck commanding a motley crew whose discipline disintegrates as they slowly die of thirst and lose their sanity. He is portrayed by Bata Živojinović, which has symbolism of its own. Živojinović is sometimes called the “Yugoslav Rambo,” being the premier action star of Yugoslav cinema and the hero of hundreds of films about the partisans from the Second World War. Here he is already a senior (63 at the time of filming), still strong and still dignified, but age has already left its mark on his face. The character he portrays is likewise an ageing career soldier, someone who’s still loyal to the Yugoslav ideal even though Yugoslavia is already dead. He is out of touch, out of his mind even, but never loses his composure. Even as they’re about to die, he insists on shaving (with his impeccably sharpened combat knife) — ever the officer, ever the gentleman, ever the loyal pioneer.

Gyozden’s first counterpart is Brzi (meaning Speedy). He is a Belgrade junkie “in military therapy”: young, rash, and born to die, as people are fond of saying, wearing a uniform because he fell from an overpass into an army truck headed to Vukovar during the Croatian War. He is the son of a Yugoslav National Army officer and stereotypically hedonistic, irreverent, disrespectful of authority, enamored of the West’s culture (including drugs), and contemptuous of state myths, both the Yugoslav and the post-Serbian Yugoslav myths. He’s an ambulance driver, which is apt, since he is directionless and has been his entire life. Brzi, being the son of a career Yugoslav National Army officer, shows us Gvozden’s future: the broken branch of the Yugoslav tree, the full gas in neutral of Yugoslav nationalism, the pointlessness of it all.

His second counterpart is Veljo, a career criminal who avails himself of the loot and seems to be genuinely enjoying himself in the war. He is a worldly man; he has seen Frankfurt and Hamburg, and has robbed banks and stolen cars in every major West German city. He’s seen Amsterdam’s whores and has eaten Switzerland’s cheese and chocolate. He once stole a cistern of beer at Oktoberfest and drank it all in three days. His ease with the carnage unnerves Gvozden, but more importantly Veljo reminds Gvozden of Yugoslavia’s dark side, the state security-sponsored organized crime gangs led by men such as Željko Ražnjatović, aka Arkan [4], a criminal, war profiteer, and himself the wayward son of an army officer who had at one point been a partisan liberator. Whereas Gvozden is an officer of the Yugoslav National Army — a gentleman, a knight –, Veljo is an avatar of UDBA, the state security agency which unleashed Yugoslav criminals on the West, created the modern Serbian and Albanian mafia, and still controls political and economic life in the post-Yugoslav world. Whereas Gvozden represents what was best about Yugoslavia, Veljo represents the worst.

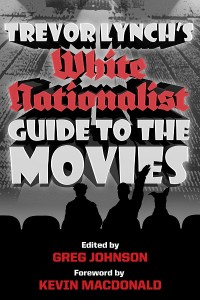

[5]

[5]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here [6]

Their reasons for fighting, however, are paradoxically the opposites of what these men are. Gvozden is fighting in vain for a state that has already been dead for three years at the time the film takes place. He refuses to let go of this dream, and it’s unclear if he can let go of it. Veljo, however, has taken the place of his younger brother, a talented archaeology student, who would have been drafted had Veljo not pretended to be him. The criminal, the spook, and the bank robber are in the war because of the one noble thing he has done in his entire life.

Even worse, Veljo embarrasses Gvozden by declaring the entire edifice of the Yugoslav state to be criminal and dishonest in a Scarface-like speech about who the bad guy is and who deserves respect and doesn’t. He lays bare the ugly truth about Yugoslavia, that its brotherhood and unity were built on dictatorship and many billions of American dollars in Western loans, Eastern privileged trade, and black funds which men like Veljo provided. The outraged Captain is ready to kill him for that.

Joined to Veljo at the hip is Marko, “the kid” or “the mascot.” Barely 18, overweight, overly zealous, sporting braces and a round jaw, probably mildly autistic, trigger-happy, and flying a Confederate flag — a symbol often used by Serbian skinheads due to the commonality of the American Southern and Serbian struggles against American imperialism –, he often screams Veljo’s name when the going gets tough (or when he accidentally riddles a child hiding in a closet with bullets). He is wounded in a Bosnian assault as his squad retreats to the tunnel. In him we see the typical wignat. Marko is ill-prepared for war and not taken seriously by the older, more experienced men. His patriotism consists of spray-painting nationalist slogans and symbols on the burned-out ruins of buildings. He is a burden to his squad and also its youngest member, a sad vision of the future. The Bosniaks capture him and torture him, broadcasting his screams into the tunnel as a form of psychological warfare.

Matching Marko in zeal but thankfully capable of carrying their own weight are Laza and his brother-in-law Viljuška (Fork). They’re peasants from Central Serbia. Laza joined up after seeing a news report in the now-infamously paranoid style of post-Yugoslav news media about the New World Order drawing up plans to carry out a genocide of the Serbs, whereas Viljuška followed him so that Laza would not be alone. Their nationalism is of the romantic variety. Viljuška wears a fork around his neck because he sees it as a symbol of Serbian sophistication — claiming it as a Serbian invention that was first used by Serbian nobility and kings while other Europeans still ate with their hands. They also clash with Gvozden. When Veljo plays the “Internationale” on his harmonica for Gvozden, Viljuška poo-poos the song.

Ironically, the Serbian knights and nobles that Viljuška looks up to are best incarnated in Gvozden himself: the stoic, disciplined warrior, ready to die with his weapon in his hand, and driven by honor and loyalty which extends beyond the death of the man he was loyal to (Tito) and the state which he served (Yugoslavia). Lazo and Viljuška see him as a relic and more or less as an outsider for his Communism. Laza’s impulsivity kills him. While the Bosniaks torture Marko, he rushes out to save him but is killed by his own grenade under fire. Soon after Laza’s death, Viljuska suffers a nervous breakdown after having to shoot an approaching woman who is shell-shocked and has been raped, but who is suspected of carrying a belly full of explosives strapped to her by the Bosniaks to turn her into an improvised and unwilling suicide bomber. Viljuška walks out of the tunnel, claiming that he’s going home. He is immediately cut down by automatic fire.

The penultimate member of the squad is the Professor. He is an actual professor, which is an honorific given to high school teachers in the Balkans. He is a Bosnian Serb who used to teach in Banja Luka, the urban center of Serbian Bosnia, even today the capital of the Republika Srpska, the Serbian subdivision of Bosnia and Herzegovina. He is a quiet man — not quite a soldier, not effective in combat, but not useless, either. While his compatriots loot jewelry, appliances, cars, and booze from the burning villages, he steals books. He appreciates poetry, gaining a grudging respect for Veljo’s native talent with words. He is nostalgic for the old system, but unlike Gvozden, realizes that it is over.

The final squad member is the film’s central character, Milan. He too is a Bosnian Serb, but a rural one. The tunnel in which the squad hides is next to his village. In the flashback sequences, the story focuses on his pre-war lifelong friendship with Halil, a Bosnian Muslim. They were kids together, chased girls together, and finally went into business together as auto mechanics. Then the war tore them from each other. Milan’s mother is killed early in the film, reportedly by Bosniaks from Halil’s detachment, which is the same one besieging them in the tunnel.

Milan is a no-nonsense character. In the Belgrade hospital where he and the Professor are recovering alongside the comatose Brzi after the fight to escape the tunnel, he is disgusted by the great city’s decadence: the rude yet promiscuous nurses and uncaring doctors who treat him like crap because they feel oh-so-urbane. When Brzi’s junkie friends come, they mock him and the war effort. When he asks one of them his nationality, he replies “d-d-drug addict.” It is probably the film’s most quoted line, and even Milan chuckles, despite himself.

To everyone else, the war is something they do, but to Milan, the war is something that happens to him. It is his village that gets looted, his mother who is killed, his best friend’s auto repair shop that burns down, his schoolteacher who is raped and used as an unwilling suicide bomber, and the tunnel of his childhood nightmares that they use as a redoubt. Ultimately, it is his land that bears the brunt of the brutal war, and recovering in the Belgrade hospital, it is made clear to him in no uncertain terms that as a Bosnian Serb, he is considered provincial, uncouth and uncivilized, and that Serbia proper is “not his land.”

All the other characters have motivations that are to a lesser or greater extent false. Gvozden fights for the vainglory of the failed Yugoslav state. Veljo fights under his brother’s name. Brzi fights to escape the horror of heroin addiction. Laza and Viljuška fight to prevent the New World Order from exterminating the Serbs. Marko, bless his soul, has no idea why he’s there except that he thought being at war would be cool. Only for Milan, and to a lesser degree the Professor, is the war something real, salient, and immediately present.

In these various characters, we see replicated the various approaches we are seeing to the Ukrainian conflict today — and possibly to every conflict everywhere on the planet. The warriors for a lost dream like Gvozden correspond to those boomers who haven’t yet realized that America is long gone and that there’s nothing left to fight for. Lazo and Viljuška are normies, caught up in anti-Russian hysteria and propaganda but who’ll soon run into the reality of the war. Brzi and Veljo represent those who run from their own pathologies [7], whether as drug addicts or criminals. Marko, poor soul that he is, is a dumb, autistic kid who gets in over his head, the Western wignat who joins the Azov battalion or the Russian skinheads rushing to kill svidomy. But Milan and the Professor are those who have no choice to enter or exit the conflict because it is being done to them, on their land and against their people. In today’s conflict, they are the Ukrainians and the Russians who live in the Ukraine to whom the conflict happens even as they participate in it.

Before we dismiss all of these people, let’s not forget that all of them have nobility in them. It is Gvozden who sacrifices himself to save the squad in the end, courageously singing an ode to Tito as he drives the ambulance truck into the Bosniak lines. Laza and Viljuška fight pro patria, for their people, and retain their childlike innocence, even amidst horror. Brzi and Veljo use their time in the war to heal and redeem themselves, and even Marko seeks out conflict as a means of self-actualiziation (though he fails in the end). The blood of warriors is always sacred.

I strongly recommend you watch this film. It is available here [8]in full, with English subtitles. The latter do not do the dialogue justice, but they’ll suffice. Unless you’re familiar with post-Yugoslav culture, the film will not be quite as impactful on you, but it is worth watching for its atmosphere, cinematography, and for being a slice of history.

There is one last character in the tunnel, an American female journalist who stows away on Brzi’s ambulance truck when he drives into the tunnel. She records the squad, drinks urine with them when the water runs out, kisses Veljo before he shoots himself, and is ultimately killed by shrapnel. Her camera likewise does not survive the encounter. She starts the film with prejudice against the Serbs as monsters, as was ginned up by Western propaganda at the time, but grows sympathetic to the squad, seeing them as human. Her presence and death are symbolic: The West’s eyes will never see what happens in the tunnel.

If you’re a Westerner, you can watch the film, but the linguistic and cultural barriers will lock you out of the full experience. It makes me profoundly sorry that we cannot share this experience. The ex-Yugoslav people hate each other, but we’re the only ones who can share the full experience of being post-Yugoslavs. It is our tragedy and joy.

Serbs aren’t monsters, even though they did monstrous things in the war. Neither are Bosniaks or Croats, although they, too, did monstrous things. What was monstrous was the system that forced these people together and forced them to fight their way out through monstrous means. An additional layer of tragedy is that this system provided an avenue for goodness, greatness, and nobility in the forty-odd years during which it existed, as we see in Gvozden and the Professor, and its value cannot be discounted or fully rejected (as it is by Veljo). There are no good guys and bad guys in life, and there are no good guys and bad guys in Pretty Village, Pretty Flame. It’s a ghastly depiction of ordinary men committing evil acts. Towards the end of the tunnel sequence, Milan and Halil shout to each other across the front lines. Who killed Milan’s mother? Who looted and burned down Halil’s shop? Was it the drekavac from the tunnel? Or did good, God-fearing, law-abiding men do these things for noble reasons?

The tragedy of a brother war is that we cannot blame the drekavac in the tunnel, nor can we exit it as a predicament without staining our souls, perhaps becoming so deformed in the process that we resemble monsters more than men in the end. I wish there were a good way out of an evil system, but I do not see it. Maybe I am blind.

I will drink and pray for every white man who falls in the Ukraine: Russian, Ukrainian, and every other nationality. I will even drink for the Chechens and the Asiatic Buryat Russian soldiers who are dying a continent away from their homeland. I will impose sorrow upon myself for these strangers because I have great sympathy for them. The Ukrainians are defending their home from Russian imperialism, while the Russians are also defending their home from NATO’s encroachment. There are no good guys or bad guys — only decent, courageous men performing monstrous acts which they have been fated to perform.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[9]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[9]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.