Racial Solidarity & Moral Hazard

Posted By Greg Johnson On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled“. . . if you told me you were drowning

I would not lend a hand.” — Phil Collins

“We must all hang together, or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.” — Benjamin Franklin

Race-conscious whites believe that our race as a whole is too individualistic compared to other races. We would do well to cultivate a feeling of white solidarity and brotherhood. This sentiment should be even stronger among race-conscious whites, lest we offer the world the absurd spectacle of a movement that preaches white solidarity but in practice is polarized [2] by sectarian wedge issues [3] and petty personal rivalries.

But we have to be careful here. Too much solidarity can be a bad thing. For instance, we all recognize that black solidarity with their own criminals is pathological. Blacks regard law and order as alien and “white,” which is true. Thus they stigmatize “snitching” on black criminals to the police. They also riot when black criminals like Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, etc. have unhappy encounters with law enforcement or armed victims.

This behavior makes it easier for black sociopaths to get away with crimes. In fact, the black sociopaths’ advocacy group known as Black Lives Matter [4] has been so successful at discouraging police from patrolling black neighborhoods and arresting black criminals that black crime is now soaring. Black criminals generally choose black victims. Thus many blacks are paying with their lives for their mindless solidarity with black criminals. Black solidarity with their own criminal element is a form of self-destructive spite. It seems that blacks hate white people, especially white cops, more than they love themselves.

If you make wrongdoing safer, you’ll get more of it. This is the meaning of “moral hazard.” Usually, moral hazards involve forcing other people to pay the costs of an individual’s bad decisions. For instance, if the government bails out lenders, they will take more risks. Obviously, a well-run society creates incentives to reduce rather than increase bad decisions. The same is true of a well-run movement. This is why we have to be careful of appeals to solidarity.

Unconditional solidarity with the wrongdoers among us is a moral hazard.

We should not extend unconditional solidarity to race-conscious whites who harm other members of our movement. These harms can range from promoting bad ideas and having bad manners — which should be called out and criticized, preferably with better ideas and better manners — to treasonous behaviors like doxing and snitching to our enemies, to outright criminal behavior. If solidarity is important to us, then we should feel solidarity with the victims.

Nor should we extend unconditional solidarity to whites — whether movement members or “normies” — who harm other members of our race at large. There are misanthropes in our cause who don’t “love white people.” They look upon white “normies” merely as raw material for their megalomaniac fantasies. But they’ll still appeal to normies for white solidarity when it is convenient. Even a whiff of such sociopathic elitism is deadly for a populist movement. If solidarity is important to us, then we should reserve it for the vast majority of decent white people, not anti-social misfits who prey upon them.

[5]

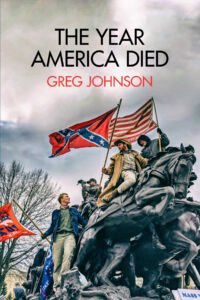

[5]You can buy Greg Johnson’s The Year America Died here. [6]

Finally, we should not extend unconditional solidarity to whites who commit crimes against other races, for instance, terrorists like Brenton Tarrant [7]. Even our enemies have basic human rights. But even if you deny that — even if you profess to care only about white people — whites like Tarrant also harm our movement and our race as a whole [8].

It is, of course, natural to feel greater affinity with race-conscious whites than for “normies” or non-whites. But we cannot lose sight of our larger goal. The purpose of white identity politics is to secure the existence and well-being of our race as a whole. That is the standard by which we must judge one another. And when a conflict emerges between members of our cause and white well-being as a whole, solidarity with our race as a whole should win out. We must always choose the greater good.

Now let’s apply this to some concrete questions from readers. First, in response to an article criticizing Nick Fuentes [9], one reader cited Benjamin Franklin’s remark when signing the Declaration of Independence that “We must all hang together, or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.” Second, a reader asked whether people in the movement should “bury the hatchet” and pull together to support the white advocates who have been targeted for lawfare for participating in Unite the Right in 2017. A third reader wants to help Jason Kessler’s defense in the Charlottesville trial, but he regards some of the other defendants as bad people, to whom he wouldn’t lend a hand even if they were drowning. He wonders if helping Kessler is right if it also helps bad people in the process. All three of these issues are related to the question of solidarity and moral hazards.

Let’s deal with the Fuentes question first. Nobody in the movement is above criticism for bad ideas, bad decisions, or bad character. Suppressing criticism in the name of solidarity creates a moral hazard. It creates an atmosphere in which bad ideas, bad decisions, and bad characters flourish. But we can’t afford that. Our cause is too important, our enemies are too powerful, our ranks are too small, and our time is too short.

However, when people like Fuentes are attacked by our enemies for being courageous and effective in advocating sound ideas — for instance, when he was deplatformed from Twitter and YouTube — then of course we should give him moral support at the very least. In such a case, doing nothing would itself create a moral hazard, since it would both decrease the likelihood of right action in our quarters and encourage wrongdoing among our enemies.

There were plenty of problems with Unite the Right [10]. There were some terrible people, terrible ideas, and terrible optics. I know what is coming in the trial. I know that we will cringe with embarrassment at the testimony, depositions, emails, forum posts, and text messages that will be offered as evidence and broadcast to the entire world.

But that does not alter the fact that the Unite the Right marchers were there to exercise their constitutional rights — and that their rights were denied by a criminal conspiracy involving the city of Charlottesville, the Commonwealth of Virginia, and a constellation of Leftist groups including the domestic terrorists known as “antifa.” The police allowed antifa to attack the Unite the Right marchers to create a pretext for stopping the event. All the violence and injuries at Unite the Right, including the death of Heather Heyer, were the consequences of the conspiracy to deny the Unite the Right marchers’ constitutional rights. Unite the Right’s participants were not attacked because of what you or I might deem bad ideas, optics, or character. They were attacked for being racially conscious whites taking a public stand against our erasure.

The same is true of the post-Charlottesville lawfare directed at the march’s organizers and participants. They are not being attacked for what you and I might reject about their ideas and behavior, but for the things that we all agree with. Thus, the attack on them is an attack on all of us. So we all need to fight back. Thus, we should set aside our differences — since those don’t really matter here, anyway — and we should offer them moral support, at the very least.

As the trial progresses, some of the defendants will make us proud. But we will also be confronted with statements, actions, and personalities that we cannot defend and that you will be asked to disavow. But hold the line. It is not illegal to be evil-minded fantasists and foul-mouthed jerks. It is not illegal to be an asshole. All the defendants, good and bad, are on trial simply for being white advocates. Make very clear that your support is not a blanket endorsement of the marchers — how could it be? — but simply a defense of their constitutional rights, as well as the basic principles of white racial activism, namely that white people are under attack, and we have the right to take our own side. On these points, at least, Unite the Right did nothing wrong.

Just as solidarity with wrongdoers within our ranks creates a moral hazard, so does a lack of solidarity when our people are persecuted for doing the right thing. If we use such attacks as occasions to air internal grievances rather than to pull together and counterpunch, we will simply encourage more sleazy legal harassment. Thus I wish the Charlottesville defendants the best. If they win, our cause will be a bit safer from lawfare. If they lose, we can only expect more of the same.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[11]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[11]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.