Black Like Me

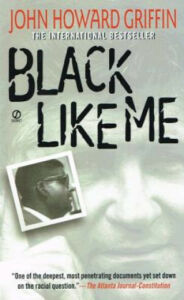

Posted By Beau Albrecht On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled“How would you feel if you were black?” We’ve all heard that one before, right? John Howard Griffin sought to discover the answer in 1959 by radically altering his appearance. His book Black Like Me (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1961) told the story. As the opening blurb explains:

Griffin worked with Martin Luther King [2], Dick Gregory, Saul Alinsky [3], and NAACP Director Roy Wilkins throughout the Civil Rights era [4]. He taught at the University of Peace with Nobel Peace Laureate Father Dominique Pire, and delivered more than a thousand lectures in Europe, Canada and the US.

Therefore, he became one of the first modern professional renegades. The most common variety includes whites who make money from being anti-white, though they usually spin their activities in much nicer rhetoric. Since publication, Black Like Me became required reading for countless high school students to raise their “awareness.” It’s been translated into sixteen languages and sold twelve million copies and counting. The royalties must’ve been amazing!

However, the reaction wasn’t always positive. In his hometown, he was hanged in effigy — the face painted half black, half white, and with a yellow stripe down its back; symbolism not too difficult to comprehend. Things did go further than that. He was beaten twice, thrashed with chains in 1964, and clobbered by Fraternity Tri-Kappa in 1975. I’d like to point out that rough stuff isn’t cool and we should be able to settle our differences peaceably. Speaking of events long ago, in the interests of reciprocity, I will be happy to make a more forceful statement against political violence, as soon as the murderer of Albert Marriner [5] is brought to justice.

Deep Cover in the Deep South

The preface begins brimming with high-minded concern for the oh-so-oppressed Negroes. My reaction is cynicism, rather than a wave of pity as intended. Sure, that stuff used to be fresh. Blacks (and their supporters) plausibly could argue that they were getting the fuzzy side of the lollipop back then. However, having heard the likes of this for the six gorillionth time, after they’ve been getting preferential treatment for longer than I’ve existed, I’m not sure whether to laugh or to groan:

The Negro. The South. These are the details. The real story is the universal one of men who destroy the souls and bodies of other men (and in the process destroy themselves) for reasons neither really understands. It is the story of the persecuted, the defrauded, the feared and the detested. I could have been a Jew in Germany, a Mexican in a number of states, or a member of any “inferior” group. Only the details would have differed. The story would be the same.

So this was 1959; merely a few years before the end of de jure segregation. (That was everything the “civil rights” activists said they wanted, prior to moving the goalposts shortly after.) Since then, society has bent over backwards [7] to a ridiculous degree to placate the blacks. Six decades and change later, professional renegades still make thundering pronouncements brimming with high-minded concern for the oh-so-oppressed African Americans. The feigned helplessness shtick hasn’t changed one bit either. For what it’s worth, this precious hand-wringing certainly is a one-sided affair. It’s none too often that blacks care about the woes of some other population.

Carrying along in much the same tenor, the first journal entry describes the author’s reasons for undergoing this. The next day, he discusses the idea with his old friend George Levitan (an “early lifer,” in case you’re curious), owner of the Sepia magazine, which in 1960 would serialize the story. The editorial director Adelle Jackson joined the conversation too. The day after, they all met with “three FBI men from the Dallas office” concerning the project. I had no idea it was that easy to grab a few glowies on the spur of the moment for a quick chat about a liberal journalism effort. Were these the same gun-toting bureaucrats who failed to protect JFK a few years later?

On the first of November, he arrives in New Orleans. Early on, he scopes out a nearly black neighborhood, wondering how he’ll cross over. (I’ll add that when he does enter into the black living space later, it’s not exactly like passing through Checkpoint Charlie.) Preparation for the disguise would involve megadoses of methoxsalen and heinous amounts of time under an ultraviolet lamp. His doctor, despite having liberal sentiments about race, warns him that he’s observed blacks becoming violent quickly and without much provocation.

By this point, I’ve noticed that even the direct quotations are just a bit stilted, similar to the rest of the book. This purplish prose in dialogue tends to make me wonder how accurate and faithful his account was.

Colored in Nawlins

After a week of skin treatments, the results weren’t perfect, but at least passable. Still, it was superior to the impersonation job of former President of the NAACP’s Spokane chapter Rachel Dolezal [8]. (Not even Patricia Krentcil [9] outdid him, whose appearance following a 2012 imbroglio [10] earned sobriquets like “Tan Mom” and “Cheese Wafer Lady.”) He shaves his head and touches up the lighter spots with dye. After the Michael Jackson transformation in reverse, he was ready to LARP as a black guy for the next five weeks. He takes a good look at himself:

The transformation was total and shocking. I had expected to see myself disguised, but this was something else. I was imprisoned in the flesh of an utter stranger, an unsympathetic one with whom I felt no kinship. All traces of the John Griffin I had been were wiped from existence. Even the senses underwent a change so profound it filled me with distress. I looked into the mirror and saw nothing of the white John Griffin’s past. No, the reflections led back to Africa, back to the shanty and the ghetto, back to the fruitless struggles against the mark of blackness.

Was all that for dramatic effect, or is this really the first time he checked himself out in a mirror since he started changing his appearance? Anyway, it’s likely he looked rather weird, since he had facial features uncommon for Africans. It’s strange that his physiognomy never gave him away.

Still tripping out about being another person (as he sees it), he goes out into the night and gets on a streetcar. He checks into a cheap hotel. A long scene unfolds in which he chats with a couple of guys in the washroom.

I told them good night and returned to my room, less lonely, and warmed by the brief contact with others like me who felt the need to be reassured that an eye could show something besides suspicion or hate.

So already he’s upset about how unfriendly wypipo are. He wakes up late next morning and hits the streets.

It was the ghetto. I had seen them before from the high attitude of one who could look down and pity. Now I belonged here and the view was different. A first glance told it all. Here it was pennies and clutter and spittle on the curb. Here people walked fast to juggle the dimes, to make a deal, to find cheap liver or a tomato that was overripe. Here was the indefinable stink of despair. Here modesty was the luxury.

He also sees a couple having a nasty argument, and soon after a guy vomiting from too much booze. (I’ll say it’s pretty hard to blame wypipo for things like that, though I’m sure it can be done.) He goes to a diner, and the difficulty of finding a Jim Crow bathroom is a topic of conversation. He boards a bus, causing his first racial gaffe.

He confides his identity to one of the locals, who had shined his shoes before but hadn’t recognized him. Even knowing the truth, he actually accepts the melanin-enhanced Griffin as a fellow black, and they hang out for a while. Sometimes tourists drop by asking where to find Negro hookers. (That one never occurred to me; is it tradition for shoeshine technicians to be well-versed on the local vice scene?) In the evening, he has a conversation with a black preacher, including:

“What do you see as our biggest problem, Mr. Griffin?” Mr. Gayle asked.

“Lack of unity.”

“That’s it,” said the elderly man who ran the café. “Until we as a race can learn to rise together, we’ll never get anywhere. That’s our trouble. We work against one another instead of together. . .”

“And the white man knows that,” Mr. Davis said.

Interesting, that. My, how times have changed.

Life’s so Tough Being Colored

The following day, the author has a chat with the diner owner. As they tell it, white college graduates had it made. As for black students:

And yet when they come home in the summers to earn a little money, they have to do the most menial work. And even when they graduate it’s a long hard pull. Most take postal jobs, or preaching and teaching jobs.

When I was attending college, I did have a fast-food job during summer vacation, as a matter of fact, and also worked rather less-than-rewarding jobs throughout. Upon graduation, I had to work for five years in some remarkably nasty companies before getting my first decent job, which lasted until the next recession. So, yeah, I totally get that. But was the guy at the diner blowing smoke, or would the world really have been my oyster if I’d graduated in 1959? He continues:

A man knows no matter how hard he works, he’s never going to quite manage . . . taxes and prices eat up more than he can earn. He can’t see how he’ll ever have a wife and children. The economic structure just doesn’t permit it unless he’s prepared to live down in poverty and have his wife work too.

OK, Boomer. Welcome to our world. The discussion goes on, later with another customer weighing in:

“They’re about fifty years behind the times,” an elderly man said. “The social scientists have shown this is wrong. Our own people have proven themselves in every field — not just a few, but thousands. How can the racists deny these proofs?”

“They don’t bother to find out about them,” Mr. Gayle said flatly.

“We need a conversion of morals,” the elderly man said. “Not just superficially, but profoundly. And in both races. We need a great saint — some enlightened common sense. Otherwise, we’ll never have the right answers when the pressure groups — those racists, super-patriots, whatever you want to call them — tag every move toward racial justice as communist-inspired, Zionist-inspired, Illuminati-inspired, Satan-inspired . . . part of some secret conspiracy to overthrow the Christian civilization.”

“So, if you want to be a good Christian, you mustn’t act like one. That makes sense,” Mr. Gayle said.

“That’s what they claim. The minute you give me my rights to vote when I pay taxes, to have a decent job, a decent home, a decent education — then you’re taking the first step toward ‘race-mixing’ and that’s part of the great secret conspiracy to ruin civilization [11] — to ruin America,” the elderly man said.

“So, if you want to be a good American, you’ve got to practice bad Americanism. That makes sense, too,” Mr. Gayle sighed. “Maybe it’d take a saint after all to straighten such a mess out.”

Was this an accurate transcription of a natural conversation? You be the judge. To me, it sounds more like one of Plato’s dialogues — “As you know, Glaucon. . .” — or philosophical chat from Atlas Shrugged. Heck, I’ve done the same thing myself. From Space Vixen Trek Episode 17: Tomorrow The Stars [12] amidst the John Galt political filibuster:

“Well, surely the people must be ripe for revolution!”

“Not so. The Raumeidechsen are masters of psychology and persuasion. Resentment is kept below the boiling point by a bread-and-circuses arrangement of lukewarm prosperity and constant entertainment. Due to the information monopoly, the people have little awareness of this pattern of exploitation and its true extent. The vast extremes of wealth are pretty obvious, but most who take exception to it can’t put all the pieces together about the situation, or lash out against the wrong targets. They know nothing about the forces that caused this, or they know next to nothing.”

“So they’re in black darkness and confusion.”

“Indeed. As for lately, the economic system suffered a catastrophic downturn five years ago, almost as bad as our own Great Depression was. Things haven’t been the same since. Their middle class is disappearing, and it’s increasingly becoming a system of haves and have-nots. There is unrest, but nothing quite like revolutionary ferment.”

“Golly, you were right; if something like that happened to the United States, we would rise up and wouldn’t stop until we took back our country and the guilty were swinging from lampposts! What’s the matter with them? Why don’t they throw off the yoke instead of tolerating this miserable system?”

“It wasn’t always this way. Overall, it’s a complicated situation.”

“I guess you have a very long infodump planned.”

“Well, you asked for it. . .”

Other than that, the next few days turn out to be a litany of microaggressions. Still, he’s scratching the bottom of the barrel for some of them. In one instance, he gazes longingly at menus in the windows of segregated restaurants, and then reflecting on the fact that it’s gauche for him as a Negro to read their menus.

Colored in Hattiesburg

Comes November 14, there’s a change of venue.

After a week of wearying rejection, the newness had worn off. My first vague, favorable impression that it was not as bad as I had thought it would be came from courtesies of the whites toward the Negro in New Orleans. But this was superficial. All the courtesies in the world do not cover up the one vital and massive discourtesy — that the Negro is treated not even as a second-class citizen, but as a tenth-class one. His day-to-day living is a reminder of his inferior status. [. . .]

Existence becomes a grinding effort, guided by belly-hunger and the almost desperate need to divert awareness from the squalors to the pleasures, to lose oneself in sex or drink or dope or gut-religion or gluttony or the incoherence of falsity; and in some instances the higher pleasures of music, art, literature, though these usually deepen perceptions rather than dull them, and can be unbearable; they present a world that is ordered, sane, disciplined to felicity, and the contrast of that world to theirs increases the pain of theirs.

Oh, I feel so guiiiilty! In brief, he decides to leave Nawlins because they just don’t hate him enough there.

He hears about a lynching case in Mississippi [13]. (He doesn’t mention the loathsome crime inspiring the vigilante action and argue that it was a case of mistaken identity; too many details would be an unnecessary complication for The Narrative. Neither is there any awareness that segregation was a measure to prevent the violence and retaliation that had characterized the Radical Reconstruction.) Then he decides this is exactly the place to go. The reader may decide whether this is because he is a glutton for punishment, or if he wants to cherry-pick the location where he’ll get the most unfriendly reception. As soon as he makes this decision, suddenly almost every white he meets is remarkably nasty, and this is before he even leaves town — purely a coincidence, of course. On board the bus at last, he spots an anti-black black who he suspects might be stoned:

He sat sidewise in an empty seat across the aisle from me and began to harangue two brothers behind him. “This place stinks. Damned punk niggers. Look at all of them — bunch of dirty punks — don’t know how to dress. You don’t deserve anything better. Mein Kampf! Do you speak German? No. You’re ignorant. You make me sick.”

He proceeded to denounce his race venomously. He spoke fragments of French, Spanish and Japanese.

Ooh, harsh! I wonder what the odd soul brother was saying in Japanese — “Nakasone was right [14]” or something? He starts drama, of course. Then the renegade black starts chatting with the renegade white disguised as black. After examining his physiognomy, he concludes that the author is part “Florida Navaho.” The entire scene seems a bit difficult to believe. For example, he proposes to go postal in the next town and offers the author the chance to assist.

We were relieved to have him gone, though I could not help wondering what his life might be were he not torn with the frustrations of his Negro-ness.

Alternatively, maybe this kid just had some screws loose — assuming he existed at all, which is looking rather iffy. Then chatting with another passenger:

He asked if I had made arrangements for a place to stay. I told him no. He said the best thing would be for me to contact a certain important person who would put me in touch with someone reliable who would find me a decent and safe place.

Like Harriet Tubman or something? Anyway, he arrives in the Hattiesburg ‘hood. Although ensconced in an oasis of blackness and as far away from the mean old crackers as he can get, he is depressed. His method acting is so good that he finds himself unable to write to his wife:

The visual barrier imposed itself. The observing self saw the Negro, surrounded by the sounds and smells of the ghetto, write “Darling” to a white woman. The chains of my blackness would not allow me to go on. Though I understood and could analyze what was happening, I could not break through. . .

Even buying food becomes an occasion for oppression porn:

A round-faced woman, her cheeks slicked yellow with sweat, handed me a barbecued beef sandwich. My black hands took it from her black hands. The imprint of her thumb remained in the bread’s soft pores. Standing so close, odors of her body rose up to me from her white uniform, a mingling of hickory-smoked flesh, gardenia talcum and sweat. The expression on her full face cut into me. Her eyes said with unmistakable clarity, “God . . . isn’t it awful?”

The place he’s staying is pretty lively, but to him, it’s yet more evidence of how downtrodden everyone is. After more contemplation of doom and gloom, he bails out and stays with a journalist friend, Percy Dale East. His liberal tendencies on race made him unpopular with the local community. After much wangst on the subject:

In essence, he asked for ethical and virtuous social conduct. He said that before we can have justice, we must first have truth, and he insisted on his right and duty to print the truth. Significantly, this was considered high treason.

On and on it goes. The author even complains, “Except for two Jewish families, they are ostracized from society in Hattiesburg.” However, the wave of long-winded purple prose doesn’t move me in the slightest. That’s because I know exactly how tolerant leftists are of other opinions. Freedom of speech was still part of normative liberalism during the 1960s, back when they were trying to abolish the in loco parentis rules on campus and to legalize pornography. Lately, all those fine scruples went right out the window; they propagandize the public with their information distribution monopoly comprised of the converged opinion-forming institutions, and also are notorious for suppressing and punishing dissenters.

Colored in Mississippi Again

The journalist drives him back to New Orleans. Immediately he gets a bus ticket to Biloxi. (Why not just ask to be dropped off there instead, or get a bus ticket in Hattiesburg?) During the pointless layover in Nawlins, he sees a bulletin taped on the bus station’s bathroom wall. Someone else walks in and chuckles at it.

I read the neatly typed NOTICE! until I saw that it was only another list of prices a white man would pay for various types of sensuality with various ages of Negro girls. The whites frequently walk into colored rest rooms, Scotch-tape these notices to the wall. This man offered his services free to any Negro woman over twenty, offered to pay, on an ascending scale, from two dollars for a nineteen-year-old girl up to seven fifty for a fourteen-year-old and more for the perversion dates. He gave a contact point for later in the evening and urged any Negro man who wanted to earn five dollars for himself to find him a date within this price category.

Yeah, sure. We’re to believe that nobody got offended by this highly immoral solicitation and took it down. This even includes the author who was taking his artificially induced négritude more seriously than Jomo Kenyatta. On the contrary, he sees half a baguette in the trash can and imaginatively weaves a narrative in his head, considering the wasted food as proof that someone saw the advertisement and pimped out a girl. Riddle me this: why didn’t the whites who allegedly “frequently walk into colored rest rooms” post their lonely-hearts notices in the women’s room instead? That would go right to the source, and cut out the middleman too. Other than that, this menu format beginning with 20-year-olds giving it up for free, and ending with the maximum $7.50 “cheese pizza [15]” bonus, seems rather hokey.

Finally in Biloxi, he soon finds an opportunity to discuss the segregated beach. After that, he begins hitchhiking. It’s unclear why he stopped travelling by bus, especially given how much he’d been deathly afraid of the local crackers a few days ago.

I must have had a dozen rides that evening. They blear into a nightmare, the one scarcely distinguishable from the other.

It quickly became obvious why they picked me up. All but two picked me up the way they would pick up a pornographic photograph or book — except that this was verbal pornography. With a Negro, they assumed they need give no semblance of self-respect or respectability.

So apparently in 1959, it was a tradition in Mississippi for whites to give rides to blacks for purposes of locker room talk. Well, that one’s new on me — assuming the author wasn’t jazzing up the story considerably, if not making it up entirely. He did give a couple of examples; the first was verging on the “scary redneck with green teeth” type from Central Casting, and the second sounded like he’d been reading too much Wilhelm Reich [16]. To the latter, the author explained:

“Our ministers preach sin and hell just as much as yours,” I said. “We’ve got the same puritanical background as you. We worry just as much as white people about our children losing their virginity or being perverted. We’ve got the same miserable little worries and problems over our sexual effectiveness, the same guilts that you have.”

He appeared astonished and delighted, not at what I said but at the fact that I could say it. His whole attitude of enthusiasm practically shouted, “Why, you talk intelligently!” He was so obtuse he did not realize the implied insult in his astonishment that a black man could do anything but say “yes, sir” and mumble four-letter words.

Did he apprehend the irony when he wrote it? Here he was in Negro disguise, white knighting (if you’ll pardon the expression) for blacks as if he were one. Then he feels offended that the driver seemed to find him to be as articulate as a white guy. That discussion becomes a sociology lecture with plenty of Rousseauian “blank slate” theory [17].

Colored in Alabama

In Mobile, he attempts to look for work during three days, but with no success, discussing it at length. Of course, employment searches are seldom fruitful in merely three days, but that’s not the point. He was trying to demonstrate that if you’re colored, you can’t get a good job in Alabama. The reasons will be clear very shortly.

Then he’s back to hitchhiking, encountering — surprise, surprise — a scary redneck with green teeth who wants to know about his sex life, the most menacing and unpleasant thus far. He also admits to quid pro quo sexual harassment in hiring black ladies. It’s obvious that the scary redneck with green teeth was a disgrace to his people, assuming that he was more than just a product of Mr. Griffin’s fertile imagination. There is, of course, no way to corroborate what was or wasn’t said in these conversations with the string of scary rednecks with green teeth, so all that should be considered essentially hearsay from a source with an ax to grind.

Then he stays the night with a black family of very modest means.

After supper, I went outside with my host to help him carry water from a makeshift boarded well. A near full moon shone above the trees and chill penetrated as though brilliance strengthened it.

Black Like Me is written in diary format, and the above entry is from November 24, apparently recapping the previous night. Just for giggles, trying to find something that I can corroborate, I consulted a 1959 lunar calendar [18]. It turns out that November 23 had a waning half-moon which would not have appeared “near full.” Sure, this is nit-picking, but it demonstrates either inaccurate recollection or embellishment; much as I suspected about some other parts of Black Like Me. It would be interesting to compare the book to the serialized magazine version and see how the story grew, in case any of us here have some back issues of Sepia.

Paragraph after paragraph go toward contemplating the poverty of his hosts, such as:

And yet misery was the burden, the pervading, killing burden. I understood why they had so many children. These moments of night when the swamp and darkness surrounded them evoked an immense loneliness, a dread, a sense of exile from the rest of humanity. When the awareness of it strikes, a man either suffocates with despair or he turns to cling to his woman, to console and seek consolation. Their union is momentary escape from the swamp night, from utter hopelessness of its ever getting better for them. It is an ultimately tragic act wherein the hopeless seek hope.

That doesn’t change the fact that they would’ve been doing better if they hadn’t had more kids than they could afford. The purple prose continues, a thundering jeremiad condemning white oppression. Six decades and change later, the baloney is getting pretty stale.

The November 24 entry finishes with him leaving the shack in the swamp and catching a bus to Montgomery. At the beginning of the trip, he looks in a bathroom mirror and notes:

My hair had grown to a heavy fuzz, my face skin, with the continued medication, exposure to sunlight and ground-in stain, was what Negroes call a “pure brown” — a smooth dark color that made me look like millions of others

Now hold that thought. Then he arrives in Montgomery that night.

Liar, Liar, Pants on Fire

The November 25 entry has an interesting item:

The hate stare was everywhere practiced, especially by women of the older generation. On Sunday, I made the experiment of dressing well and walking past some of the white churches just as services were over. In each instance, as the women came through the church doors and saw me, the “spiritual bouquets” changed to hostility. The transformation was grotesque. In all of Montgomery only one woman refrained. She did not smile. She merely looked at me and did not change her expression. My gratitude to her was so great it astonished me.

Oh, what sorry examples of Christian hypocrites! Start feeling guilty immediately, you Dixie broads, while your virtues are weaponized against you!

Not so fast. The problem is that November 25, 1959 was a Wednesday [19], and he’d arrived there last night. Therefore, he cannot have been in Montgomery on Sunday to observe Southern belles giving him the stink-eye as they left church. The previous diary entry was the day before, and the next was two days later, so it’s hardly possible that he was confused about which day he was writing about for the Wednesday 11/25 entry.

Could this be an unexplained back-dating? As we’ll see shortly, he changes his appearance back to white by the following weekend. Shortly after that, he leaves for Georgia. The Sunday 11/29 entry begins:

Montgomery looked different that morning. The face of humanity smiled — good smiles, full of warmth; irresistible smiles that confirmed my impression that these people were simply unaware of the situation with the Negroes who passed them on the street — that there was not even the communication of intelligent awareness between them. I talked with some — casual conversations here and there. They said they knew the Negroes, they had had long talks with the Negroes. They did not know that the Negro.

So obviously he was presenting as white on the one Sunday he actually was in Montgomery, with nothing in the 11/29 entry stating otherwise. Call it more calendrical nit-picking if you will, but the point is that particular vignette maligning “hateful” white church ladies did not happen.

Why am I the one to call out this simple but telling error at long last? Apparently the reviewers were so taken in by the story of his adventure as an oppressed Negro that they assumed he was telling the truth. Therefore, nobody thought of checking his narrative against an old calendar. He was so caught up in liberal self-righteousness that he lied to make his own people look bad. What else was he lying about then?

Not so Colored in Alabama

The brief November 27 entry shows him having a change of heart about the soul brother act:

My heart sickened at the thought of any more hate. Too, I wanted no more sunlight until I had the medication sufficiently out of my system to allow me to lighten.

Then on Saturday:

I decided to try to pass back into white society. I scrubbed myself almost raw until my brown skin had a pink rather than black undertone.

Apparently it works. That, and dark clothing for contrast, was all he needed for his skin to be passably white, no longer “pure brown” as he’d described himself four days ago. A black teen activates a switchblade as he approaches. He’s not the least bit offended, and in fact follows and tries to talk to him. (If this is true, then John Howard Griffin was a major league dumbass.) However, the youth won’t talk to him. Meanwhile, he’s able to get into segregated areas without problems. His African credentials had been unquestioned throughout. Then after the scrub-down, nobody seems to be applying the paper bag test, asking about his ancestry, or anything of the sort.

On December 1, he begins switching back and forth by using skin dye. In other words, the disguise by now was simply blackface, rather like certain vaudeville acts or Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer. (It would’ve blown his cover if he’d missed a spot at any time.) After documenting more racial gaffes on buses:

The shift back to white status was always confusing. I had to guard against the easy, semi-obscene language that Negroes use among themselves, for coming from a white man it is insulting.

Shee-it! [20] This is one of the few references to Ebonics. I do recall at one point that a drunk guy is referred to as “gassed,” but quite curiously, there’s little other evidence that anyone is speaking in the usual dialect, despite many direct quotations. For some reason, most of the spoken language is in the same slightly stilted style as the rest of the book.

Colored in Georgia and Beyond

He gets on the bus for Georgia, documenting another transit microaggression. He arrives at a Trappist monastery in Conyers, just the occasion for some ultracalvinist pieties. After that:

I then had a visit from a young college instructor of English — a born Southerner of great breadth of understanding. He told me that his more liberated views of the Negro were in such contradiction to those of his elders, his parents and uncles, that he no longer went home to visit them.

As we can see, shunning family members over social and political matters is nothing new.

On December 4, the professor drives him to Atlanta where he teams up with a photographer. Soon after, the author launches into a sanctimonious gripe about pro-white bias in the media. Cry me a freaking river, pal. . . Then after discussing education and pro-white bias in banking, he discusses housing:

Every leader is interested in better housing. Many professional men, particularly doctors like F. Earl McLendon, have developed residential areas as their contribution to the cause. Atlanta has virtually miles and miles of splendid Negro homes. They have destroyed the cliché that whenever Negroes move into an area the property values go down. In every instance, they have improved the homes they have bought from the whites and built even better ones. The philosophy here is simple. Try to anchor as many Negroes as possible [21] in their own homes.

I haven’t been to Atlanta in ages, but maybe Jim Goad [22] can fill us in on all that.

On the home stretch, he and the photographer go back to Nawlins. The pictures appear soon after; as one might suspect, he’s pretty dark but the physiognomy doesn’t match. (Perhaps his incongruous appearance accounts for some of the odd looks he complains about constantly.) He returns to his DFW area home, but the bloviating continues. In 1960, the publicity for the story begins. It discusses much MSM attention, including a Mike Wallace interview. He started getting considerable friction among his local community. This part of the book is boring, sanctimonious, and long-winded liberal mush — not entirely different from the rest.

Extended Overtime

The edition I’m working from has an epilogue in 1976. Early in this liberal mush, it discusses how in the days of segregation, blacks had to pretend to be happy:

Once when I was employed at some menial job I noticed that one of the white middle-aged bosses kept looking at me and getting more and more irritated. I could not imagine what I was doing wrong. Certainly I was sad, and that sadness must have shown, for finally he yelled at me: “What’s eating you, anyway?”

“Nothing,” I said.

“Well, what’re you so sullen about?” he said.

“Nothing,” I repeated.

“Well, if you want to hang on to this job, you better show us some teeth.”

And I did my grinning.

There are times in the story when he discusses trying to find work and never getting anywhere, generally when he’s not preoccupied with discussing segregation, taking bus rides, or hitchhiking with scary rednecks with green teeth. However, he never discusses actually getting a job, much less the “you better show us some teeth” incident. It’s difficult to see how that wasn’t notable enough to record in one of his diary entries. Was he trying to spice up the story long after the fact in 1976?

After that, he discusses “civil rights” activism during the 1960s. This includes the necessity of taking measures to avoid sneaky character assassination tactics. Despite his bitching, I’m not too worked up about it. Lately, a single politically incorrect remark or social media post from several years back can end a career, so he can take his fine liberal scruples and shove it. Talk to the hand, Mr. Griffin; the face don’t wanna hear it.

Eventually the professional renegade becomes an early multiculturalism mystagogue. This part is fairly boring. However, there’s one interesting bit in which a black industrial psychologist (I have no idea either) is asked if he agrees that a meeting, in which Protestants and Catholics came to agreement, marks a historic moment:

The doctor said, “It’s true that I have a good job in this town, and I seem to be respected, and I am certainly paid a wage commensurate with my skills. But — so long as I have to house my wife and children in a town twenty miles away because I can’t buy, rent, lease or build a home here, don’t expect me to get too excited over your ‘historic turning points.'”

Translation: “All or nothing, my way or the highway.” (The next act, of course, is to move the goalposts — the old Leon Trotsky perpetual revolution shtick.) I’d bet dollars to donuts that whenever he did get to move into a formerly white living space, he started bellyaching about something else. Much to their credit, the white liberals in attendance actually didn’t respond with self-abasing genuflection, but instead considered him an ingrate and regretted inviting him. Then John Howard Holier-Than-Thou Griffin butted in to shame them.

Other than that, he weighs in on the 1967 riots [23], remarking that city governments weren’t appeasing blacks enough, as in some cases he had recommended. The irony escapes him that they burnt down their cities soon after de jure segregation was over. Wasn’t all that the very concessions they had been demanding? One might suspect they’d taken integration not as justice granted, but as a sign of weakness and a launching point for new demands — “my way or the highway” all over again.

The patterns of the exploding inner cities began to emerge. From the black man’s viewpoint it often looked as though black people were being driven to flare up which would then justify suppression by white men on the grounds of “self-defense.”

This “you drove us to riot so you could brutalize us” shtick is a very interesting deflection of blame. Classical conditioning is a much better model. (What will happen if you buy a candy bar to get a screaming kid to shut up? It’s the same principle.) If adult spoilt brats learn that truculence and violence will get payoffs, then how will they behave in the future? Consider also the usual liberal hand-wringing and protracted discussions about “root causes” following every major riot, often with extra concessions, goodies, or protection money bundled with the attention. That sounds more like rewarding bad behavior than “suppression by white men.”

Much more commentary follows, for example:

On the streets, young black men would call out, “Take ten!” to one another. Whites thought they were talking about a ten-minute coffee break. What they were really saying was that this country was moving toward the destruction of black people, and since the proportion was ten whites to every black, then black men should take ten white lives for every black life taken by white men.

Showing his true colors, John Howard Griffin never utters a peep of condemnation about this call for massacring his own people. He places blame entirely on whites for these turbulent times. He explicitly denies that Communists [24], black militants [25], or outside agitators [26] had the least bit to do with any of it. On rare occasion during his 1959 adventure, he briefly mentioned black bad attitudes. However, every last one of them is an innocent lamb by the time he’s recollecting the 1960s, including the ones contemplating mass murder.

Later, he discusses how many of the white Gutmenschen in activism and academia were shocked and offended as they started getting pushed aside from the movement they helped build. (At last that makes for some fun reading.) He comes to make a halfhearted endorsement of black separatism. I’m certainly not going to argue against it, but doesn’t that shoot down his entire operating premise that integration is an absolute necessity?

Extended Overtime, Bis

As if he hadn’t rambled sufficiently so far, there’s his 1979 swan song, “Beyond Otherness.” It’s fairly short (mercifully) and takes a universalist tone. However, I’ve had enough of his liberal mush by now.

Extended Overtime, Ter

Robert Bonazzi provided the fiftieth edition Afterword. Much of it is biographical. The rest is liberal mush.

Six Decades Later

So what do we make of all this liberal mush woven together in a lachrymose morality play? It’s pretty clear that John Howard Griffin went into this experience trying to chow down on the discrimination buffet, and he got what he wanted. Many of his observations are subjective, and spun the most anti-white way possible, including several exercises in mind-reading. On the other hand, blacks come across nearly as blameless angels. If this weren’t enough, some elements of the story seem embellished, improbable, and in one instance obviously fabricated. Despite all these challenges to its objectivity — one could argue that all the stretching should put it in the “fiction” section of the library — it remains one of the top classics of the white guilt genre.

Granted, blacks surely were offended by having to go to the back of the bus, use different lunch counters, and all the rest of it. Still, integration didn’t turn out to be a panacea. Simply put, it was yet another one of those leftist social engineering projects that didn’t work as advertised. The judges and politicians enacted desegregation without consulting the public about it.

In so doing, they exposed the white population to the elevated black crime rate [27], which still remains a problem. Consequentially, whites fled countless neighborhoods over the following decades, which decayed into slums after the blacks moved in. The property damage over the years is about the equivalent of an ICBM salvo. School quality took a nose dive [28] in many urban areas too. Other than all that, the public was told that desegregation would end the tensions between the races. The young Boomers took it as an article of faith that they were inaugurating an era of good feelings and brotherhood, best exemplified in St. Dr. Rev. MLK Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech written by his talented consigliere Comrade Stanley Levison. It certainly didn’t work out that way, now did it?

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: