Are We Really Anglo-Saxons?

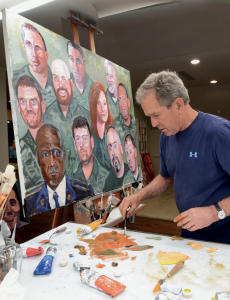

Posted By Robert Hampton On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledGeorge W. Bush is back in the news to promote his horrible picture book, Out of Many, One. The picture book, as its title evokes, urges readers to see America as a vast, multicultural landscape where everyone can belong. Most of his public statements in support of the book have touted mass immigration and the superiority of immigrants. He’s backed amnesty and denounced the Republican Party [2] for its “nativism” and “isolationism.”

His latest salvo attacks the GOP for standing for WASPs, a group that Dubya himself belongs to. He made this criticism in an interview where he was asked about the aborted America First Caucus wanting to uphold “Anglo-Saxon traditions.” He says that kind of rhetoric will make Republicans [3] go “extinct.” “I know this — that if the Republican Party stands for exclusivity, you know, used to be country clubs, now evidently it’s white Anglo-Saxon Protestantism, then it’s not going to win anything,” he said.

Anglo-Saxons made a long-awaited return [4] to public discourse last month due to the America First Caucus. The caucus — which was supposed to be joined by Marjorie Taylor Greene, Matt Gaetz, and others — was roundly denounced as a white nationalist vehicle over its evocation of Anglo-Saxon traditions, opposition to mass immigration, and promotion of European-style architecture. The group was nothing of the sort, but GOP leaders forced it to shutter before it even began over the controversy. It was an interesting experiment and does show the growing popularity of nationalist ideas within the Republican Party.

But George W. Bush does have a point, even if his solution is completely wrong. If the GOP did just stand exclusively for white Anglo-Saxon Protestantism, it would be doomed to failure. Most white Americans are not WASPs and don’t identify as such. Of course, it wasn’t the purpose of the America First Caucus to make the GOP a WASP revanchist party. The caucus merely wanted to make the GOP more like the Donald Trump of 2016.

But its use of “Anglo-Saxon” brings up crucial questions: what is white American identity? And is it “Anglo-Saxon”?

For most of America’s history, the majority of whites could see themselves as Anglo-Saxon and would have been comfortable describing themselves as such. Even if they weren’t necessarily English, they fully assimilated to Anglo-American culture and were practicing Protestants. They may have been Scottish or had some German ancestry, but that wouldn’t have made them wince at touting the virtue of the Anglo-Saxon. Woodrow Wilson, a Scot, wrote glowingly [5]of the “Saxon race” earlier in his academic career. But, as president, he told King George V [6]:

You must not speak of us . . . as cousins, still less as brothers; we are neither. Neither must you think of us as Anglo-Saxons, for that term can no longer be rightly applied to the people of the United States . . . there are only two things which can establish and maintain closer relations between your country and mine: they are community of ideals and of interests.

[7]

[7]You can buy Greg Johnson’s White Identity Politics here. [8]

That statement reflects the change in American perception of white identity. Wilson would’ve never dismissed the idea [9] that his nation was a white man’s country — he opposed Asian immigration and supported segregation. But he knew that his Democratic party depended on the support of non-Anglo European immigrants — Slavs, Italians, Irish, etc. They didn’t see themselves as Anglo-Saxons and they didn’t see the English as cousins.

Wilson’s statement didn’t end the positive references to Anglo-Saxon in American life. Shortly after he left office, the nation passed the 1924 Immigration Act [10] to preserve its Anglo-Saxon character. Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard turned out best-sellers warning of the dangers posed to the Anglo-Saxon race. Even President Calvin Coolidge proudly talked about the Nordic people who settled this land.

But the 1920s were the last hoorah for the positive references to Anglo-Saxons and presidents speaking of the American people as Anglo-Saxons. The New Deal coalition defeated WASP hegemony and heralded a new era of American identity. The “nation of immigrants” civil nationalist claptrap took hold of public discourse at this time. After the 1930s, the only ones who would positively refer to Anglo-Saxons or describe themselves as Anglo-Saxons were Southern segregationists. And this petered out over time. In the post-World War II era, Anglo-Saxon became a pejorative for the arrogant native stock who didn’t want to accept Ellis Islanders. It formed the core of WASP, the favorite term to deride heritage Americans.

Since then, the only positive mentions of the Anglo-Saxons came from the likes of Samuel Huntington and Antonin Scalia. Huntington reframed “Anglo-Saxon” as “Anglo-Protestant” for his book Who Are We? This friendlier term didn’t refer to the people of America, but its culture. There were no paeans to the Saxon race in Huntington’s book. Antonin Scalia took a similar approach to Anglo-Saxon heritage. “American common culture, which nobody has to belong to, originates with English culture. That includes Shakespeare, it includes nursery rhymes that we all know and use as examples. That’s our common culture, and I think the framers recognized that,” he said in a 2006 interview [11].

This is the more politically acceptable Anglo-Saxonism that the America First Caucus was likely referring to. Even a swarthy Italian like Scalia can count himself an Anglo so long as he subscribes to the common culture.

But is this really what 21st-century whites can relate to? The answer to that is “not really.” Few whites read Shakespeare anymore and it’s unclear if people fight and die for nursery rhymes. The common law tradition does provide the basis of our legal system, but that’s not something that people identify with. It’s not a rally cry or something for people to base their entire lives around, especially when it’s open to all. We can argue that it’s a heritage worth recovering and upholding, but it’s not something that meets people where they’re at.

It comes across as a more politically correct and inclusive way of saying white culture. Yet, it also alienates and befuddles whites.

Anglo-Saxon may be more acceptable (but just barely) in public discourse than white, but it doesn’t resonate with whites at all. Most whites don’t know what an Anglo-Saxon is, and it sounds too medieval. You might as well say you’re standing up for Gondorian traditions. Few white Americans identify with their Anglo ancestry. In the 1980 census [12], British American was the largest ancestry category for whites. Thirty-one percent of Americans said they had British ancestry. In 2000, less than 9 percent claimed English ancestry, and less than 2 percent claimed Scottish ancestry. Some of the change is due to the then-new category of American, which over 7 percent of Americans claimed. But that still leaves a lot of white Americans who decided they weren’t British anymore.

Though we do have an Anglo-Protestant culture — or least the remnants of one — most Americans prefer to see their ethnic background as something other than British.

A central challenge for us is how we define ourselves. We no longer are a people that sees itself as Anglo-Saxon, even though we do speak English and Shakespeare may still seep into high school English classes. This is not our identity anymore. On the other hand, as the great Sam Francis noted [13], “white” by itself is not a sufficient identity either. Our people are not simply going to rally around the color of their skin; they need traditions, culture, and history to go along with it.

The best identity for us is actually quite obvious: American. The challenge is to make American mean white American and to strip this term from its vulgar meaning. American doesn’t mean American citizen in the same way French citizenship doesn’t make one a Frenchman. When we say American, it means an ethnocultural group. “America for the Americans;” “Americans First;” “American heritage;” etc. These phrases wouldn’t mean all American citizens, they would mean only our people.

It may not be glamorous and it may be cringe when used by the powers that be, but it is an identity that resonates with our people. They see themselves as Americans — not as Anglo-Saxons, European-Americans, or “Amerikaners.” We can add descriptors such as heritage, old stock, and certainly Native (because we are the actual Native Americans). But American remains the central term.

George W. Bush was right: the Right can’t just stand for white Anglo-Saxon Protestantism. It must stand for white Americanism, plain and simple.

* * *

Don’t forget to sign up [14] for the weekly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.