Ich Klage an Pro-Genocide Nazi Propaganda or Humanitarian Masterpiece? Part 2

Posted By Travis LeBlanc On In North American New RightPart 2 of 2 (Part 1 here [2])

A trial is held and several witness are called. Hanna inherited a substantial sum when her father died, and Hanna’s brother Edward — who never liked Thomas and thought he himself should have received the money — accuses Thomas of killing his wife in order to get her inheritance. There is also speculation about Thomas’ relationship with his lab assistant, a ravishing 26-year-old blonde named Barbara Burckhardt. Perhaps Thomas spending all that time in his laboratory searching for a cure for his wife’s disease was just an excuse to spend time around Barbara.

Much of the early part of the trial involves trying to establish whether or not Thomas’ wife requested to be euthanized. The housekeeper finally confirms this when she reports on the confrontation between Heyt and Dr. Lang wherein Lang revealed that Hanna had previously asked him to euthanize her. Thomas gets a lucky break when a medical expert testifies that it is possible that Hanna had in fact died from the disease itself, which had shut down her respiratory nerves. Based on this testimony, the judges downgrade the charges from murder to attempted murder.

The only witness who does not testify is Dr. Lang, who cannot be reached. We then see Dr. Lang at the house of a family whose daughter Dr. Lang had gone above and beyond to save. The child is now deaf, blind, demented, and living in an institution. The parents say they don’t know why Dr. Lang had not simply allowed the poor girl to die. The doctor visits the child at the institution and immediately realizes that he made a serious error.

As the judges deliberate behind closed doors, they debate the philosophical pros and cons of euthanasia — and here’s where the propaganda hits you in the face:

Bald guy: If someone is terminally ill and would rather die, why should he keep living? If someone asks to die, doctors should be allowed to help.

Moustache guy: That is all fine and good. I agree. But can these decisions on life and death be left to doctors?

Bald guy: Of course not. They’d take on the responsibility for it. Commissions must be appointed, proper tribunals made up of doctors. But something must be done. It cannot go on like this.

Christian minister: It is God’s will. He sends suffering so that men will follow his cross and attain eternal bliss.

Major: My dear sir, I would like to believe that God is not that cruel. Nor the pastor, by the way.

Military man: Yes, well, gentlemen, just a few weeks ago I had to give my old hound the mercy shot. He was blind and lame, but otherwise, he had faithfully served me his entire life. And if a hunter doesn’t do that, he is a harsh fellow, not an honorable huntsman.

Moustache guy: Yes, but those are animals.

Military man: Yes, but are people to be treated worse than animals?

Judge: It’s not that simple. The right to kill shouldn’t be given to a doctor alone. These final medical decisions should be left to the state. We would have to pass laws for these “medical courts.”

Major: But as soon as possible. I’m an old soldier, gentlemen. It’s evident to me that our state demands a duty to die, if need be. But then it should also have to give us the right to die if necessary.

Judge: Sure, Major, but the laws applicable here are still different.

Major: Of course we will judge Professor Heyt under current law.

Judge: That goes without saying.

Major: But allow me to say, the law is not here to prevent people from worthy moral acts. If that’s the case, the law must be changed.

[4]

[4]You can buy Irmin Vinson’s Some Thoughts on Hitler & Other Essays here [5].

Dr. Lang finally shows up, but rather than acting as a witness for the prosecution, he vigorously defends Thomas and says that he is not a murderer. The film ends with Thomas accusing the system of cruelty and demanding that they give the verdict. The movie ends before the final verdict can be delivered, however. It is up to the audience to decide whether Professor Heyt acted within his rights.

Some may believe that, if you overlook the fact that it was (allegedly) made by the Nazis to build support for state murder programs, it’s Gone with the Wind. But then again, why would you want to overlook that?

Now, certainly some readers may feel that the Nazis require no apology, but for those who do, there are several reasons why you could or should ignore the film’s historical context and just enjoy it for what it is.

1. Ich Klage an does not advocate for what Aktion T4 was actually doing. The only kind of euthanasia the film advocates is the voluntary euthanizing of the terminally ill. It says nothing about euthanizing mentally ill people, children, or anything else along those lines.

2. While Ich Klage an may have been intended as propaganda to build support for Aktion T4, it never actually served that role because the program ended before the film premiered. Rumors about Aktion T4 killings had been circulating since 1939, when mentally-impaired German citizens began to be sent to undisclosed locations. Their families would then receive a letter informing them that the patient had died. These rumors finally led to large-scale protests in July 1941 that had been encouraged by the Bishop of Münster. Not desiring any domestic unrest while the war was still underway, Hitler ended the Action T4 program on August 24, 1941, five days before Ich Klage an premiered at the Venice Film Festival [6]. In other words, there‘s no blood on the film’s hands.

3. There’s not much in Ich Klage an to indicate that it was made with Nazi support. Hanna receives a letter in the opening scene; the envelope has a big, bold swastika on in. There is another scene where a portrait of Hitler can briefly be seen in the background. Beyond that, it’s easy to forget that you are watching a movie made in the Third Reich, with Nazi support.

I watched a video [7] in which some liberal academics were kvetching about Ich Klage an. It was not as informative as I had hoped, but there was an interesting part where Dr. Volker Roelcke of the University of Giessen talked about showing the film to his students in Germany:

I have used this film repeatedly in seminars with many students in Germany and other occasions. One time, at an evening event in Switzerland . . . I didn’t tell the audience anything about the context. I just showed the film, first of all. Then there was a discussion starting, and it was a discussion about the legitimacy of active euthanasia. And only once I introduced the context, people became very irritated.

Even though Roelcke is in the camp which holds that Ich Klage an is genocide propaganda, he acknowledges that they find nothing offensive in it on its own merits — unless you tell them about its background. It’s only with context that people are outraged by it.

4. Hollywood produced a very similar movie about “mercy killing” only a few years later.

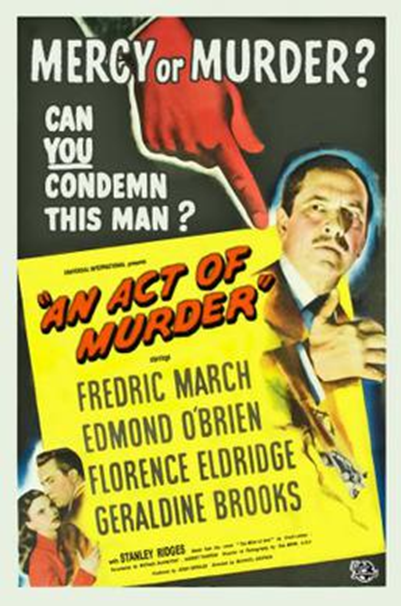

Seven years after Ich Klage an premiered, in 1948, Universal Pictures released the film noir An Act of Murder [9]. It is based on the novel Die Mühle der Gerechtigkeit (The Mill of Justice) by the Austrian Jew Ernst Lothar [10] and shares many of the same plot elements as Ich Klage an. A judge’s wife is found to have a terminal brain tumor which cause her frequent, excruciating headaches. Just as in Ich Klage an, the judge initially tries to hide the illness from his wife. There is also a scene where a policeman puts a dying dog out of its misery, which is similar to one in Ich Klage an where Thomas’ lab assistant euthanizes a mouse. After the judge watches his wife suffer in agony for some time, he resolves to put her out of her misery by driving her off a cliff. The twist ending is that during the ensuing trial, the judge is exonerated when the autopsy reveals that his wife had already died from a suicidal overdose before he drove her off the cliff. This twist keeps the movie from having to deliver a final verdict on the morality of compassionate euthanasia, but it presents case for it nonetheless.

An Act of Murder was not some throwaway B movie or poverty row exploitation film. It was a prestige picture from a major studio that starred a two-time Academy award-winner, and it was presented at Cannes. On top of this, An Act of Murder’s director [11], both [12] screenwriters [13], and Ernst Lothar, who wrote the novel it was was based on, were all Jewish. So how “Nazi” could Ich Klage an possibly be if a group of Jews made what is basically the same movie?

At this point one might ask, given that Ich Klage an didn’t in fact advocate for what Acktion T4 was doing and thus wasn’t promoting it, what was the point in making it? Even though it does not advocate for what Aktion T4 was doing, from the Nazi perspective it didn’t need to. What the film really does is the equivalent of abortion advocates who ask pro-lifers if a woman who gets pregnant during a rape by a stranger should be forced to carry the child to term. They put forward a scenario in which abortion is at its most defensible in order to put their opponents in a catch-22. If one insists that the woman should have to give birth to the baby, he looks like a monster who is not only indifferent to the suffering of others, but is willing to inflict even more for the sake of abstract principles. But if one concedes that abortion is justified in that particular case, then he has lost the debate. The conversation is no longer about wanting abortion or not, but rather how much abortion one wants. The pro-lifer no longer opposes abortion in principle, which completely changes the dynamic of the conversation.

Likewise, Ich Klage an presents a scenario where euthanasia is at its most defensible: voluntarily chosen by the victim of an incurable disease that guarantees a joyless existence, and moreover where it is administered by a doctor who did everything he could to avoid it — up to and including trying to cure the disease himself. This is done to convince viewers to stop opposing euthanasia in principle and instead get them to ask, “How much euthanasia do you want?”