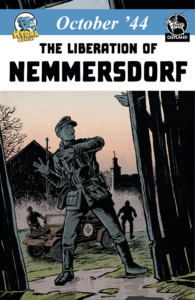

October ’44 — The Liberation of Nemmersdorf: A Graphic Novel

Posted By Clarissa Schnabel On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledOctober ’44 — The Liberation of Nemmersdorf [2]

Written by Markus Pruss

Illustrated by Paul Freytag

Translated by Nils Wegner

Dresden: Hydra Comics, 2023

In February 2023, German comics publisher Hydra Comics [3] released their first historical piece: Oktober ’44 — Die Befreiung von Nemmersdorf [4] (October ’44 — The Liberation of Nemmersdorf). Hydra describes itself as a publisher for “non-conformist” art — meaning, of course, a publisher for the dissident Right.

Although most of the reactions were supportive, there were those critics who condemned turning the events at Nemmersdorf into “light entertainment” that kids could browse through while eating hamburgers. Of course, those very same critics also pointed out in (self-)righteous indignation that they had never read a graphic novel in all their lives and would never do so. The reason for this is probably a still-widespread ignorance of comic book culture in Germany. In contrast, the bande dessinée has long been used in France and Belgium to tell “grown-up” stories (I hesitate to use the word “adult,” but yes, those are out there, too), as well as to depict the lives of historical figures — and to educate. A popular series aimed at older children for that purpose, for example, is Les enfants de la Résistance [5]. The most prominent example in the English language is, of course, Art Spiegelman’s Maus.

The Liberation of Nemmersdorf has now been released in an English translation [2], so I thought it would be a good occasion to talk about what the graphic novel is and what it is not. First of all, it is neither light entertainment nor a book for children, hamburger-eating or otherwise. Hydra put the recommended age at a minimum of 16 years; in other words, reader discretion is advised. Although the presentation is not overly graphic (haha), it can’t skip the gruesome facts. Nemmersdorf is also, contrary to what the usual suspects might think, anything but Right-wing propaganda.

[6]

[6]You can buy Savitri Devi’s Defiance here. [7]

On October 20, 1944, Red Army troops captured the German village of Nemmersdorf in East Prussia, about 40 kilometers from the German-Soviet border. A German counterattack liberated Nemmersdorf two days later, only to find 110 persons — 26 inhabitants, 82 refugees, and two French prisoners of war — brutally murdered. Several of the women had been raped. The findings that were published in the Völkischer Beobachter on November 2, 1944 have of course been denied and disputed ever since, a common accusation being that the photos, if not the events themselves, had been staged by the German Ministry of Propaganda.

There is, of course, a kernel of truth to it. Yes, the story made for excellent propaganda insofar as it warned both German soldiers and civilians of what would happen if they ever let Soviet soldiers set foot on German soil. It was meant to reinforce the people’s will to fight. Propaganda has been used — and continues to be used — in any war and at any front for that very purpose. This doesn’t mean that it’s all lies. As the later conduct of the Red Army showed, it is sadly only too likely that the events of Nemmersdorf happened exactly as reported.

Let me quote from the Hydra blog [8] (my translation):

The recently opened Dokumentationszentrum Flucht, Vertreibung, Versöhnung [Documentation Center Flight, Expulsion, Reconciliation] in Berlin is an example of the taboo surrounding and the suppression of the events that took place in Nemmersdorf in October 1944. In the exhibition’s conceptual design, the center contextualizes the massacre of Nemmersdorf historically in a few sentences, but in the completed, permanent exhibition on the upper floor, “Nemmersdorf” is not mentioned in even one syllable on the text panels! This is all the more surprising given that in most publications about East Prussia in 1944/1945, Nemmersdorf is considered to be the signal for the flight and expulsion of the Germans. Our unconventional comic October ’44 — The Liberation of Nemmersdorf would like to close these historical gaps in the German culture of remembrance by depicting the suppressed experiences of the Second World War from the point of view of our German grandparents and great-grandparents . . .

It tells the story of young East Prussian sons and war-wounded veterans who are sent by the military leadership on a suicide mission against a superior Soviet force, then experience the fear and horror of war, and are finally able to liberate the village after all. The author of the comic, Markus Pruss, is a historian who specializes in the flight and expulsion of Germans from East-Central Europe. Contrary to Soviet denials, his recent discoveries in the archives of the German Foreign Office and the Freiburg Military Archives make it exceedingly likely that there were indeed a large number of assaults by Soviet troops on the civilian population in Nemmersdorf as well.

Markus Pruss added an extensive editorial section to this comic; it is almost as long as the graphic novel itself. Pruss presents his findings in it, along with his sources. One of the more obscure facts about the liberation of Nemmersdorf, for example, is that, as Pruss writes, it was not as heroic as some eyewitness accounts painted it. Because of a lack of coordination during the advance, German troops may have been subjected to so-called friendly fire. And speaking of the obscure, unless you are quite versed in this topic, you may have heard of Nemmersdorf, but not of the people involved. I certainly hadn’t. The graphic novel seeks to redress this oversight. The story is told through the eyes of ordinary people — those unknown individuals who were caught up in the events at Nemmersdorf.

Paul Freytag’s illustrations are in a straightforward, clear style, which is fitting for a comic book that could serve as an educational resource — although I won’t get my hopes up on that ever happening.

If there is one thing that I would criticize about Nemmersdorf, it is, ironically enough, its pedagogical mission. (A very German attitude, I might add!) Now, considering everything stated above, I understand why this particular approach was chosen; and as a somewhat source-obsessed researcher myself, I both congratulate and sympathize with the author. But — notwithstanding the topic itself — this approach feels a bit heavy. Les enfants de la Résistance, for example, also features editorial sections, but at a ratio of 48 pages of story to seven pages of background information.

Still, this is a minor complaint. All in all, Nemmersdorf is a successful start to Hydra’s new Ostland label, and I look forward to future installments.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [11]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall [12] page.