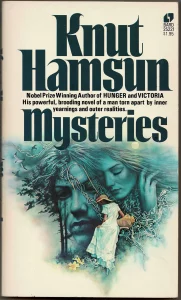

Mysteries: Knut Hamsun’s Brilliant Misfire

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledThe following is being published in honor of Knut Hamsun’ [2]s 164th birthday on August 4.

It’s one thing to attempt to write a great novel. It’s something else entirely to write a novel to prove a point. The latter is what the young Knut Hamsun attempted to do in 1892 with his second novel, Mysteries. It was a good point, but that doesn’t necessarily make Mysteries a good novel. But it is still a good novel. Perhaps not a great one.

Psychology was something that nineteenth-century authors typically took for granted. Characters were stable individuals made to fit into familiar types and set against each other for the reader’s entertainment. Insights into the mind, or soul, if they were to occur at all, came as a result of outer conflict, not from tapping into inner turmoil. Going any deeper than this just wasn’t done very often. Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick and Stendhal’s The Red and the Black stood out in this regard. Of course, so did Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. It was upon this cutting edge that Knut Hamsun attempted to hone his skills when writing Mysteries.

The final product, while startlingly original for its day, becomes most useful when studying the evolution of the novel as an art form — which is most appropriate for a classroom. As an early modern psychological novel, Mysteries was certainly ahead of its time; but given how ephemeral the appeal of such novels became as the twentieth century progressed, this turns out to hardly be a selling point.

The story opens on Johan Nilsen Nagel, a brilliant yet mentally unstable stranger who approaches an unnamed coastal town in Norway. He’s in a garish yellow suit and carries a medal around that he did not win and a violin case without a violin — all meaningful details, given that he intends to draw a tremendous amount of attention to himself, and is not exactly who he says he is. He quickly gains the reputation for being fabulously wealthy, but only because he sent himself telegrams which implied he had great wealth and then left them in the lobby of his hotel, where others would see them and spread the word.

The reader soon learns that weaving complex webs of deception is Nagel’s modus operandi, although at first this is not obvious to the townsfolk, who are quite understandably fascinated by him. He assumes the role of both protector and benefactor of the town cripple, but then bullies him terribly when they are alone. He regales the townsfolk with fantastic stories, and never seems to pass up an opportunity to flout the rules of etiquette and show himself in the worst possible light. If he contradicts himself for those who’ve been paying attention, so much the better. He’s liable to skewer liberal and socialist alike, and has a Nietzschean attitude towards religion (as well as a soft spot for the humble townsfolk). And don’t get him started on Maupassant’s “crotch poetry” or that two-bit blowhard Leo Tolstoy, whose teachings aren’t “a hairsbreadth deeper than the hallucinations of the Salvation Army.”

He becomes infatuated with the local beauty, Dagny, who is engaged to a sailor who is then at sea. While professing his undying love for her, he courts the town spinster with equal ardor. He attempts to buy a broken, rotting old chair from her for far more than it is worth. As an honest soul, she keeps refusing — and this only makes him want her more. All this while he skulks around Dagny’s house at two in the morning. He is so obsessed with her that when her dog threatens to expose him by its barking, he gives it a dose of poison from the vial he carries around in his vest pocket.

[3]

[3]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here [4].

Why does he walk around with a vial of poison in his vest pocket? That’s a mystery, isn’t it? “Well, what of it?” Hamsun writes in one of Nagel’s many inner monologues. “Ah, who can fathom what takes place in the human soul!”

As Nagel spends more time among the locals, his talent for anecdote begins to enthrall them. He tells of wood elves and blind angels, of a beauty with a hunchbacked sister, of a miser presiding over a procession of empty carriages, of a slattern who becomes a brilliant writer, and of a recurring image of a boat with a blue sail shaped like a half-moon. Because this is a psychological novel, Hamsun employs a panoply of modernist tricks in order to lull the reader into believing these stories somehow have meaning; switching tenses, inserting dialogue without quotes, and shifting back and forth from third- to first-person narration are three of the big ones. Having read a lot of twentieth-century fiction which also employs such techniques, the best I can say is that in Mysteries at least they aren’t annoying.

Perhaps the best moment occurs when Nagel, who is at a bazaar, is asked by the townsfolk to play the violin. He at first refuses, because from the beginning he had always denied knowing how to play. But he then changes his mind:

When the acrobats were off and the applause had died down, he stood up; he said nothing, not a word, but stretched out his hand for the bow. The next moment, while the audience was leaving its seats and making for the entrance, while all was noise and loud talk, he suddenly began to play and soon imposed silence every- where. This little broad-shouldered person bobbing up in his loud yellow clothes in the middle of the hall struck everybody with astonishment. And what did he play? A song, a barcarole, a dance, a “Hungarian Dance” of Brahms, a passionate potpourri, a raw, surging strain that penetrated everywhere. He put his head on one side; the whole thing had a mystic look, his sudden appearance outside the program, his striking exterior, his wild dexterity, which bewildered his hearers and made them think of a magician. He kept on for several minutes and the audience sat motionless; he changed into a mournful strain of immense pathos, a fortissimo of trumpet-like power; he stood perfectly still; nothing moved but his arm, and he kept his head on one side. He had turned up so unexpectedly, surprising even the bazaar committee, that he actually took these townspeople and rustics by storm; they couldn’t grasp it; in their ears this music sounded much better than it was, for it seemed right enough, though he was playing with careless impetuosity. But after four or five minutes of it he suddenly swept his bow across in a gruesome chord, a desperate howl, a lamentable wail, so impossibly harrowing that no one knew what was coming next; he gave three or four strokes like this and then broke off and took the violin from his chin.

After this, the town cannot get enough of Johan Nilsen Nagel. They hail him as a genius — but he swears to anyone who’ll listen that he’s no genius. And here is perhaps the only time when the beautiful, awful truth comes out of Nagel’s mouth: He is good enough on the violin to know how bad he really is! Compared to concert violinists, his performance is sloppy and undignified. Of course, most of the townsfolk can’t tell the difference. But he can. And it haunts him.

Mysteries is an undisciplined, meandering, longwinded — yet brilliant — misfire of a novel. The main character has a mesmerizingly creative mind and is a top-notch intellect. This makes Mysteries memorable for its depiction of the loneliness and frustration a man must feel when his IQ is two standard deviations higher than everyone else around him. Hamsun’s mistake, however, is to imply that the profound mysteries behind Nagel’s psychological suffering are somehow universal, and therefore both tragic and instructive. They aren’t. Nagel is simply off his rocker. He suffers from violent mood swings and feels compelled to behave in a bizarre, erratic fashion. Sometimes he’s kind and generous, but at other times he’s cruel and destructive. This is certainly an unfortunate condition, but hardly a hook to hang a story on. Would we want to learn about healthy living by following a former athlete who’s dying from a congenital disease? It’s kind of like that.

In Hamsun’s day, the mind was more of a mystery than it is now — which is why Mysteries has not aged well at all. If Nagel were alive today, he’d be diagnosed with some kind of acute mental disorder and prescribed any number of anti-psychotic, anti-anxiety drugs, which would most likely allow him to live a longer, more stable — although probably less eventful — life. And yes, I am aware that such drugs can be overprescribed. But considering what happens at the end of Mysteries, that would be a risk worth taking in the case of Johan Nilsen Nagel.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [5]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[6]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[6]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.