Famine in 1930s Kazakhstan: The Forgotten Holodomor

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledSarah Cameron

The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan

Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2018

See also: What is the Metaphysics of the Left [2] & Nietzsche and the Psychology of the Left [3]

Strikingly ignorant, malignantly cruel, with no concept of history, with but an elementary knowledge of social production, with little productive capacity, with no constructive ability, [Bolshevism] would be ludicrous were it not for the sentimental, weak-minded followers who, steeped in idealism and fanaticism, really believe in a Bolshevik Utopia, where free milk will run in the water mains and life may be supported without toil, where knowledge may be gained without effort, and where the established truths of the centuries will be overthrown by soviet resolutions. — Ole Hanson [4], Americanism versus Bolshevism (1924)

The Kazakhs and the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic

In the early 1930s, while the multicultural Soviet Empire [6] was starving the Ukrainians [7], a similar famine was ongoing in Kazakhstan. The famine’s cause was the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’s simplistic and wrongheaded views on land use, economics, and society, combined with their hatred for a nation that was independent of their multicultural experiment. In the end, nearly 1.5 million Kazakhs — a quarter of the population — died. Other deaths included non-Kazaks who had been deported to gulags in Central Asia.

The Russian Empire conquered Turkistan [8] — the area comprising Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan — starting in 1865. Russian settlers began to develop the area shortly thereafter. The Russian experience in Turkistan is very similar to the American settlement of the Great Plains states except that in the Russian case, the Turkistan natives — a mixture of white and Asian Turkic peoples, as well as Indo-Europeans Tajiks — didn’t vanish into small, reservation-bound groups as the American Indians did. Nor did the natives carry out massacres of the Russians, as the Indians did to American whites.

Part of the reason for this was that the people of Central Asia were fully connected to the outside world. They’d been living along the Silk Road and the nomadic highway of the Eurasian Steppe since time immemorial. They were also nomadic pastoralists rather than hunter-gatherers. Further is that during the initial stages of Russian settlement, the Russians did not settle in the pasturelands which the Kazakhs used.

[9]

[9]You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s Solzhenitsyn and the Right here [10].

When the Bolsheviks took power in the former Russian Empire [11], which became the Soviet Union, they set about implementing their ideology. In Ukraine and Kazakhstan, the results were disastrous — and deliberately so.

The Kazakh people’s origins go back to a political split during the late stages of the Mongol Empire. As it was fracturing, a group of Turkic people who rejected the Uzbek Khan migrated to what is now Kazakhstan, intermarrying and forming a nation united by blood ties. They trace their ancestry to a possibly mythical ancestor named Alash and his three sons: Bekarys, Akarys, and Zhanarys. The sons led their own hordes, which included clans consisting of subgroupings called auls. Aristocratic Kazakhs are called “white bones” and commoners are called “black bones.” There are also Kazaks who claim descent from Genghis Khan as well as those who claim descent from the Prophet Muhammad. In traditional Kazakh society the “wealthy” were those with ordinary ambitions who made up the mid-level clergy and leadership, and were known as bais. When the Communists came to power in Kazakhstan, they claimed that the bais were exploiters. It became a term akin to kulak in Ukraine.

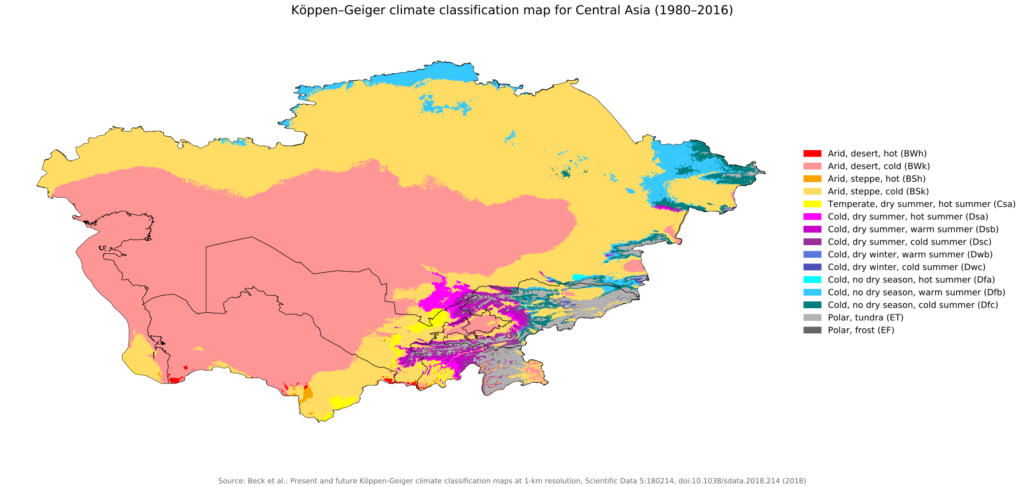

The Russian settlement of Kazakhstan went well enough in the northern, less arid part of the region. In the arid steppes, however, settled agriculture was difficult to establish. The problem was the climate. Kazakhstan has a continental climate which roughly trisects the region. In the northern fringe the climate is Dfb [12], or humid continental, akin to the eastern parts of the Dakotas. In the central zone it is Bsk [13]: cold and semi-arid, akin to the climate of the eastern portions of Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. In the south there is a cold desert. The Russian settlers therefore prospered in the north.

The boundaries of the climate zones shift yearly, depending on the winter westerlies from the Atlantic, and change as a result of the North Atlantic Oscillation [14], which is the interplay of high- and low-pressure atmospheric zones centered on Iceland and the Azores. These zones send rain east towards Eurasia. By the time the moisture reaches Kazakhstan, most of the rain has already fallen in Europe. The Kazakh way of life was adapted to this climate, however, as the Kazakhs moved their flocks and herds to the areas with the best grass on a seasonal basis.

Communist ideology held that all peoples would become Communist via stages, one of which was establishing a nation in those areas where there wasn’t one already. In keeping with this doctrine, the Soviet government created what became the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic in 1920 and staffed it with Bolshevik true believers. The most critical of them was Filipp Goloshchekin [16], a Jew who became the leader of the Kazakh SSR in 1925.

The leaders of the Soviet Union tended to be non-Russians who were alienated from the Russian ethnos. They were highly-educated midwits who tended towards criminality. Goloshchekin demonstrated these traits, having been responsible for murdering Tsar Alexander II and his family.

The Soviets’ goal in Kazakhstan was to use the example of the American settlement of the Great Plains to create a meatpacking industry which would rival that of Chicago.

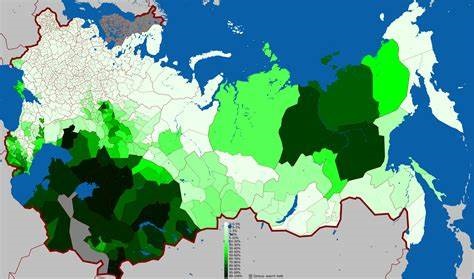

[17]

[17]The location of Russians in Kazakhstan. When Kazakhstan was part of the USSR, the number of Russians increased until they became a majority. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Kazakhs reversed much of their own Great Replacement.

Misreading the American settlement of the Great Plains

The first problem with this plan was that the Communists were misreading the American situation. They ignored warnings that had been issued by Tsarist officials about the problems involved in grain production on the arid Eurasian Steppe. The Americans had settled the Great Plains more carefully, although they, too, had problems when settlers plowed up the grasslands while thinking they could change the Plains’ climate [18] to suit their ways in the early twentieth century.

Many American explorers of the semi-arid plains remarked upon the difficulty of settling a cold, semi-arid climate zone. Captain William Ludlow [19] led an expedition to the Black Hills and the western Dakota Territory, an area similar to Central Asia, in 1874. As he wrote in his report [20]:

Water is scarce, and almost invariably alkaline, even in running streams, from the presence of a salt which forms a component of the clayey soil. The rivers are small streams of great comparative length, which, from absorption and evaporation, shrink in their downward course, and are frequently dry at their mouths while flowing freely a hundred or two miles above. The seasons of spring and fall are exceedingly brief. The winter snows are rapidly disposed of in the spring and rain-falls are unfrequent until cold weather in the fall, which soon again merges into winter. By July 1 the grass is fully grown, and in another month has turned dry and yellow, cured to hay upon the ground and readily burned.

The Americans also had private enterprises which could issue stock to raise the necessary capital to crisscross the area with railroads. Any citizen was free to use the railroads however they wanted. After the Civil War, Texas cowboys moved enormous herds of cattle north and across the plains to Kansas, where they would be shipped to the meatpacking centers in Chicago. The cowboys were free to spend or save their wages as they saw fit, and while there were cattle rustlers and brigands attempting to steal their cattle, these men were not employed by the United States government.

The homesteaders who settled the prairie were free to adopt new technologies, such as windmills to bring up groundwater. Families had access to loans and capital to develop their farms. The American pioneers plowed up the land, however, and when drought came – coincidentally, at the same time as the famine in Kazakhstan — they were free to leave. Many headed to California, turning Los Angeles into an extension of Middle America. Those who stayed changed the ways in which they used the land to better conform to the environment.

American socialist enterprises on the Great Plains, such as they were, likewise conformed to existing conditions. The New Deal Leftists didn’t resettle Americans in collective farms; they built dams and roads. Water rights were sorted out through a lengthy process of court cases, and the resulting body of laws came to be known collectively as riparian water rights [21]. This allowed water to be used effectively.

Those who settled the American plains were families of the same racial stock as the railroad owners and the meatpacking magnates. They understood each other. Leftist critiques of the “capitalists” in the US were akin to William Jennings Bryan’s statement that [22]

[t]he man who is employed for wages is as much a businessman as his employer. The attorney in a country town is as much a businessman as the corporation counsel in a great metropolis. The merchant at the crossroads store is as much a businessman as the merchant of New York. The farmer who goes forth in the morning and toils all day, begins in the spring and toils all summer, and by the application of brain and muscle to the natural resources of this country creates wealth, is as much a businessman as the man who goes upon the Board of Trade and bets upon the price of grain. The miners who go 1,000 feet into the earth or climb 2,000 feet upon the cliffs and bring forth from their hiding places the precious metals to be poured in the channels of trade are as much businessmen as the few financial magnates who in a backroom corner the money of the world.

In other words, the common people didn’t want to overthrow the system, but rather bring it into alignment with their interests. William Jennings Bryan’s populism was of an entirely different bent than that of the Communists.

The Famine

In contrast, the Soviet leaders were entirely hostile to the Kazakhs. They didn’t understand Kazakh society, and they imposed their ideology onto a people who had no history of being an “industrial proletariat.” They also did not take environmental factors into account as the Americans were doing, ruling by decree and applying Soviet methods that were completely unsuited to the conditions. They collectivized the Kazakhs in the same way as the Ukrainians, with some differences. In the same way that the kulaks were allegedly the problem in Ukraine, the Kazakh bais were blamed for Kazakhstan’s problems.

The Communist government gave commissions to pro-Communist Kazakhs to dispossess the bai and seize the Kazakh nomads’ livestock, which were then taken to railheads and kept in poor conditions where disease was rampant. Many of the animals died, leaving corpses that led to further unsanitary conditions and further increased the death rate. The Kazakhs themselves were herded into collective farms where there was no food or the possibility of getting any. Starvation naturally followed. The crisis was further compounded by the fact that deportees were being sent to Kazakhstan from other parts of the USSR, and upon arrival found themselves without food. As the famine deepened, the Kazakhs were forced to resort to theft and murder, and in some cases even cannibalism.

[24]

[24]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Here’s the Thing here. [25]

The attack upon the bai damaged Kazakh society in many ways. They had been part of Kazakhstan’s traditional social structure for centuries, so their removal disrupted everything. The links which had kept the Kazakh body and soul together were severed, and even their marriage customs were overturned. Many Kazakhs ended up joining the Soviets and preyed upon their ethnic kin. Some tried to flee to the cities, such as they were, but they had no urban job skills.

Many Kazakhs fled to western China, where they had relatives and the climate was similar, panicking the Soviet government. Anti-Communist forces had set up bases in the region, and the Chinese government had no ability to control its side of the border, so the Soviets established a security force to prevent the Kazakhs from leaving, although it wasn’t very effective in stopping a nomadic people who were highly skilled at travelling across the vast grassland.

The famine in Kazakhstan ended around the same time that the one in Ukraine did, and as with Ukraine, it is not known why Stalin suddenly changed his policies at that particular time. It could be that he recognized that Kazakhstan’s economy had completely collapsed and that the disaster could end up threatening his regime. In any event he replaced Goloshchekin with Levon Mirzoyan [26], who took steps to end the crisis, including by allowing the Kazakhs to return to the steppes with their livestock, offering inoculations, and providing food. This process was aided with abundant rains in 1934, which led to a strengthening of the grasslands and prevented crop failures.

Both Goloshchekin and Mirzoyan were later executed on Stalin’s orders during the various purges of Communist officials. Kazakh society, for its part, remained badly hurt. The Kazakhs’ nomadic lifestyle never fully returned after the famine. Instead, auls and other sub-groups took over entire collective farms, leading to the return of a reduced form of pastoralism that incorporated tractors and other modern equipment. It wasn’t until 1960 that livestock numbers in Kazakhstan returned to their pre-famine levels. The camel populations likewise recovered, although not to the same number as before.

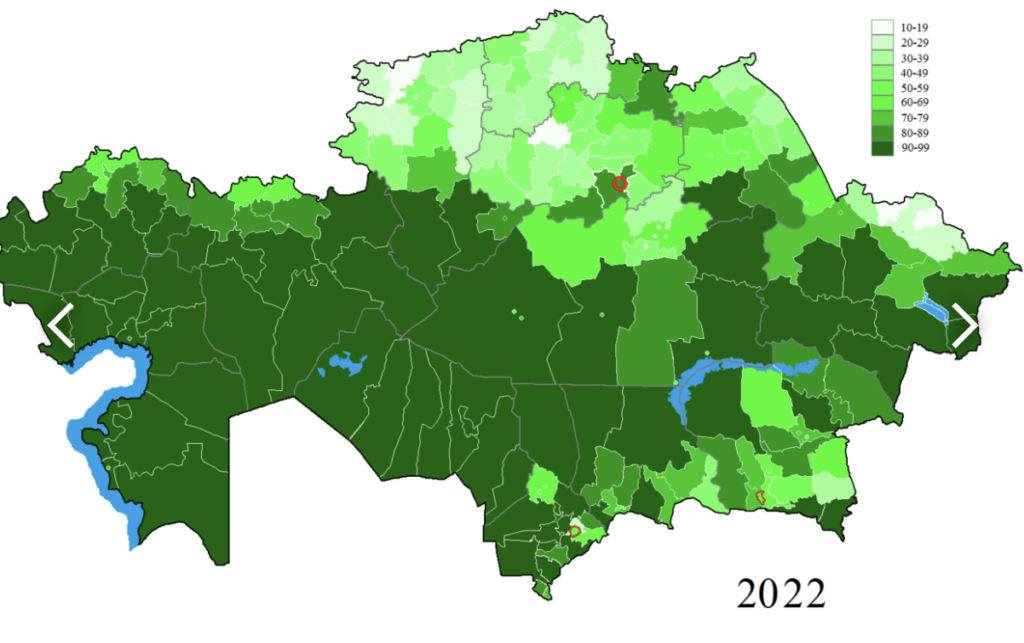

The Kazakhs who survived were entirely dependent upon the Soviet state. They had not been conscripted into the Russian military in the First World War, but served in the Red Army in great numbers during the Second. Kazaks remained a minority in their own country throughout the Soviet era and only recovered majority status after the collapse of the Evil Empire. The famine is not remembered in Kazakhstan in the same way as Ukraine’s famine is in that country, however; today it is largely forgotten.

It is no surprise that the Soviet Union and its unworkable system collapsed in 1991. What is more puzzling is how the Soviet experiment remained viable for so long. It has been amazing to see the return of Marxist and Communist ideology in so many areas of American life in recent years. It should be remembered that Communism leads to disaster everywhere it is applied — whether in industrialized nations, or on the Eurasian Steppe.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [27]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall [28] page.