Prioritizing Prestige Over Accomplishment: Britain from 1950 to 1956

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledCorrelli Barnett

The Verdict of Peace: Britain Between Her Yesterday and the Future

London: Faber and Faber, 2001

See also: The Collapse of British Power [2], The Audit of War [3], & The Lost Victory [4]

[This] book — again like its predecessors — is written from the standpoint of ‘Total Strategy,’ a concept first defined in the preface to The Collapse of British Power [2] in 1972 as ‘strategy conceived as encompassing all the factors relevant to preserving or extending the power and prosperity of a human group in the face of rivalry from other human groups.’ The fundamental factor in the total strategy of a nation lies in industrial and commercial performance, for it is this which determines power and wealth alike. Yet that performance is in turn governed by a nation’s character: its skills, energy, ambition, discipline, adaptability, and enterprise; its beliefs and myths. Moreover, national character also governs other key factors making for total-strategic strength: cohesiveness and efficiency in social and political structures; dexterity, foresight and willpower in the conduct of foreign and domestic policies. — Correlli Barnett [5]

British historian Correlli Barnett [6] finished his quartet on the collapse of Great Britain as a world power with The Verdict of Peace (2001). It focuses on decisions the British made between 1950, when they entered the Korean War, and 1956, when they invaded the Suez Canal and suffered a humiliating defeat as a result. Barnett ruthlessly examines the decisions made at all levels of British society during this time and shows that a nationwide focus on prestige rather than genuine accomplishment created the conditions for unnecessary British decline.

Korea, a strain on an overburdened system

On June 25, 1950, Communist North Korea invaded non-Communist South Korea. The North’s invasion sent shockwaves across the world. Prior to then, the Communists in the Soviet Union had typically expanded their sphere of influence through manipulation, such as rigged elections in Poland [7] or the coup in Czechoslovakia [8]. Korea was different, with T-34 tanks being sent en masse across a national border. Every senior diplomat and politician of the day believed that such “line crossing” had to be met with force anywhere, at any time, for any reason. The fact that the North Koreans were seeking to reunite their own country, which had recently been divided by foreigner, made no difference.

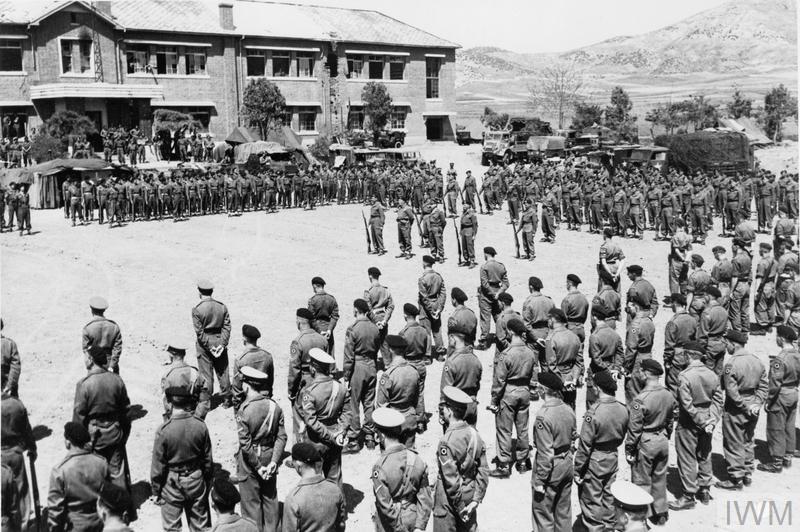

[9]

[9]The British Commonwealth Division in Korea required the repositioning of troops from other parts of the vast British Empire.

The Truman administration organized South Korea’s defense through the United Nations. The British were trapped into joining this effort, although the war was not entirely in their national interest. Barnett writes:

The untimely march of the North Korean army into South Korea therefore shut Britain into the trickiest of all her twentieth century total-strategic dilemmas. For whereas in 1914 she had in reality been a first-class power, and in 1938-39 at least the dominant voice in an alliance of near-equals, she was now hopelessly outweighed by America’s plenitude of wealth and power. The truth therefore was that in contrast to 1914 to even 1938 — 39 she enjoyed in 1950 little real independence of decision. (p. 12)

Involvement in Korea required the British to create and field an expeditionary force that pulled resources away from other operations across their Empire. They had also decided on embarking upon a vast rearmament program, which cost the British taxpayer dearly while cutting into other revenue-producing industries. Every factory that was switched to producing military equipment meant a loss of goods for export. Britain’s military in the 1950s was expensive, overdeployed, and often deployed on missions purely for prestige, such as in Korea or the Middle East, rather than in support of vital British interests, such as protecting West Germany.

[10]

[10]The Avro Vulcan was one of three jet bombers developed by British Aviation to provide for an independent nuclear deterrent for the United Kingdom. Development of the Vulcan was classified as being of “supreme importance” in 1950, although it took six years for it to enter service. The Vulcan’s setbacks, delays, and cost overruns are similar to the American defense industry’s pathetic performance today.

British industry & British labor

Britain’s industrial plants were outdated everywhere. They had not been streamlined for efficiency in the same manner as had been recommended by American experts such as Frederick Winslow Taylor [11]. Higher education was primarily focused on teaching the sons of the wealthy and upper classes in how to be gentlemen. There were few schools that taught industrial or business management. Skilled tradesmen and draftsmen were also in short supply.

As a result of this, British factories failed to develop interchangeable parts. American and German auto companies, for example, had already done so, which meant that an individual part could be used in several makes of car. British-built engines, suspension systems, and so on were unique to each model of car. All of British industry suffered from this problem, such as their ships, which added to the costs of producing and maintaining them.

The British labor unions also presented a problem. American unions [12] had shed themselves of Communist sympathizers during and shortly after the Second World War. British unions, however, were riddled with Communists who took orders from Moscow. One especially large strike was called in England shortly after the Soviets suffered a setback in the success of the Berlin Airlift.

American unions were large amalgamations. All types of American auto workers were in a single union, which only went on strike for the sake of clear and important objectives. In contrast, British unions were fractured; the pipefitters, boilermakers, and carpenters all had their own organizations. This meant that a dispute between two unions over who did what on a particular job could blow up into a full work stoppage until the dispute was resolved. British unions were also prone to strike for petty reasons and without clear goas. Strikes became so frequent that orders went unfilled, customers went elsewhere, and the opportunity for the British to capture global markets slipped away.

[13]

[13]An idealized drawing of the Berkeley Atomic Reactor being built. Developing new industries was made more difficult by British labor laws because the nature of new technology meant that jobs could not be neatly categorized into older labor types. Unions fought each other viciously over who did what in this new environment, costing time and money.

A perfect example of these problems was a strike at the Austin Motor Company in 1953. A union man, Mr. J. McHugh, was working in the Austin Sheerline [14]’s paint shop. When production on the unwieldy Sheerline slowed because of declining orders, McHugh was moved to the A90 line. But unfortunately, the Austin A90 was “a stylistic abomination dreamt up for the American market and now doomed by the market’s failure to appreciate it” (p. 187). Austin therefore decided to cut the A90 line and carried out a mass layoff on a last in, first out basis. Having only recently been transferred, McHugh was one of those laid off. His union organizers saw this as an attack on the union itself, leading to a huge three-day strike that was resolved by a government Court of Inquiry. The Court determined that the union had unfairly favored McHugh and that the strike did not conform to the union’s internal laws. In the end, McHugh didn’t get his job back and the equivalent of 239,000 working days were lost.

[15]

[15]The Austin A90 Atlantic. Its story is emblematic of the lack of technical acumen and short-sighted unions that destroyed British industry.

Barnett writes:

But mere statistics cannot properly record the ramifying harm inflicted on British industry and commerce by these repeated blockades. For they meant export delivery dates missed and foreign customers infuriated; factories held up for want of raw materials and equipment from abroad; wholesalers and retailers running out of imported foodstuffs; transport to and from afflicted ports backing up in standstill and confusion; telegrams and telephone calls crowding an out-of-date and already overloaded telecommunications net as victims of the blockades tried to sort out their troubles; and an immense waste of time and effort by ministers and civil servants in attempting to deal with the strikes and their immediate impact. More insidious still was the moral harm done to Britain at home and abroad by such spectacular mutinies, further helping to convey the impression of a nation without disciplined purpose, and instead blindly intent on self-mutilation. (p. 254)

The Sterling Area

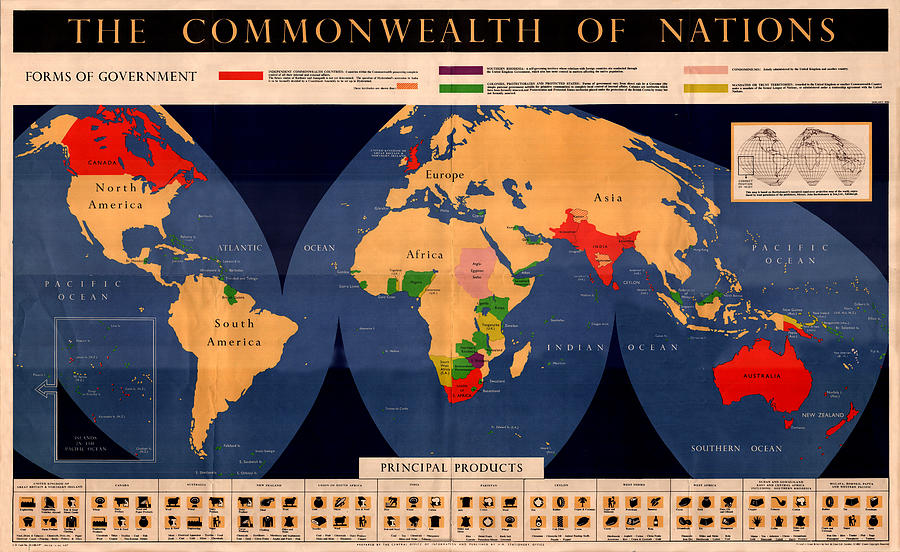

Another problem for Britain in the 1950s was maintaining the Sterling Area, those parts of the British Empire and Commonwealth which used the British pound for their currency. Having a common currency across the Empire was not a problem in itself, but the British were in debt to the Americans, who required repayment in US dollars. This required exchanging sterling for dollars — and a drop in the sterling’s value made repayment difficult. The British were then forced curtail domestic consumption to avoid inflation, which would have made repaying their debts impossible. As a result, most household products in the United Kingdom continued to be rationed until the late 1950s.

[16]

[16]The British Commonwealth in 1950. All in the British Commonwealth’s nations and colonies used the British pound.

[17]

[17]You can buy Jonathan Bowden’s Extremists: Studies in Metapolitics here [18].

The British protected the value of their currency through austerity measures at home, but the back door was wide open. As a result, every nation, colony, protectorate, and so on in the Sterling Area was free to exchange pound sterling for the US dollar in large quantities, thus lowering the value of the currency — which resulted in making the balance of payments problem worse.

The British nevertheless kept the Sterling Area going for reasons of prestige. Most of the Area was poor, however, and did little purchasing of high-end British goods. Maintaining it therefore required enormous infusions of aid from the British taxpayer.

The British policy of full employment likewise presented a burden. Men in a union would remain employed even if their jobs were rendered obsolete by new technology. This was a terrible waste of resources. The British had colonies in Kenya and Rhodesia that could have taken in millions of white settlers had there been something like the Homestead Act, but instead underemployed workers remained in England – and Rhodesia became Zimbabwe.

Suez

The British were militarily overextended in the Middle East. They had originally gone there in the nineteenth century to protect the shipping routes to India. After they abandoned India in 1947, however, it meant that they no longer needed to protect the southern coast of Arabia or the Suez Canal. But the British government felt that if they left, the Soviets would move in. The fact that the Soviets themselves would have been overextended if they had done so wasn’t considered.

The entire British establishment had been shaped by the events leading up to the Second World War. After Munich, they believed that any “dictator” had to be stopped before he could become a bigger threat. It was this reasoning which led the British and Americans) to overthrow Iran’s Prime Minister in 1953 [19]. The British finally withdrew their troops from the Suez in 1954 under pressure from the Egyptians, but they signed a treaty which stipulated that they could return should the canal be threatened by an outside force.

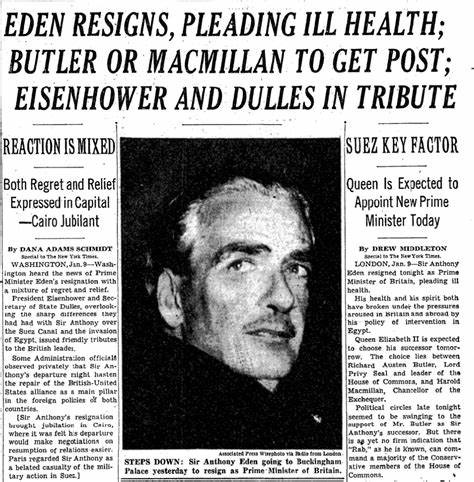

In 1956 Britain’s Prime Minister was Anthony Eden, who was squarely of the “aggression at Munich” mindset. He was certain that Egypt’s President, Gamal Nasser, was the next “Hitler.” Thus, when Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal in July of that year, which was owned jointly by the British and French, Eden decided to act. Secretly, the British colluded with the Israelis and French to take back Suez and depose Nasser. The plan was for Israel to invade Egypt, triggering the threat from an “outside force” stipulated in the treaty. The British and French would then provide “security” for the Canal by sending troops.

The Israelis invaded the Sinai according to plan on October 29. The British and French attack, which began on November 5, was flawless from a military standpoint. After some initial fighting, there was nothing stopping the coalition from going on to capture the whole of the canal. But there were several political problems. The Egyptians recognized the plot for what it was. Tensions between Eden and Nasser had been rising for months, and the Israeli military was capturing objectives in the desert that had no strategic or military value. The Egyptians then appealed to the United Nations for help.

US President Eisenhower had been opposed to the intervention. The Americans got word of the attack directly from Walter Monkton, Eden’s Minister of Defence, on October 24. American U2 spy planes had likewise observed 60 French-built jet fighters in Israel, which raised their suspicions. The US thus condemned the invasion, and the British received no effective support from the Commonwealth nations of Canada, Australia, or New Zealand.

An American condemnation would have had no impact whatsoever in 1918, but in 1956 the British were heavily indebted to the Americans, and the British economy was too plagued with problems for them to carry out independent actions. The value of the pound declined alarmingly, and the British were forced to withdraw. For the first time in thousands of years, the Egyptians had defeated an imperial power — and the British, who had been looking to restore their prestige, were humiliated.

The Verdict of Peace shows the considerable problems the British were facing as their Empire declined and finally collapsed. It is easy to be smug about their missteps in hindsight, but today Americans are making many of the same mistakes. America today is marked by “civil rights,” the Great Replacement, and endless military deployments and wars. It’s entirely possible that the US establishment will soon prioritize prestige over accomplishment as well.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [22]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[23]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[23]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.