“Sojourners in the Desert . . . Glad of Each Delay”: Meditations on the Drylands, Part I

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled5,203 words

Part 1 of 3 (Part 2 here [2])

Deserts are the strangest places on Earth.

I spent my undergraduate years at an isolated college town that sat on the fringes of a vast, interior desert. To the northwest, the great Rocky Mountains began their ascent; directly west lay No Man’s Land, but the Sun’s; to the south, the flats gradually lifted into ancient atolls, red gorges, and rock. As a native woodland creature, this dryland seemed to me like another planet. When my mother and I first drove the ten hours it took to get there, I remember being amazed at the first cacti I spotted by the highway. Even more surreal — a huge, round monstrosity made of what looked like bleached antler bone, all torturously tangled together, came bounding along a bit too near us. “What in God’s name is that?” I asked — perhaps the sick leftovers of an old Indian ritual, or crime scene? “It’s a tumbleweed,” my mother answered, like it was no big deal. And here I’d always thought that tumbleweeds were the inventions of Saturday morning cartoons — little brown balls of twigs and grass that rolled politely along during the Yosemite Sam episodes. I have news for the uninitiated: Neither do tumbleweeds “tumble” sweetly by, nor are they “weeds.” But they can mess you up.

Upon arrival, we saw welcome signs like, “Howdy, from Big Sky Country,” and my favorite: “Where the West Begins . . .” Across from campus, a tall stone building was visibly twisted — the survivor of a powerful tornado that had ripped through the town center decades before. Indeed, over the next few years I saw many fascinating and outlandish phenomena that lived up to those initial boasts. One night a few friends and I were driving home when suddenly thick clouds of dust galloping at the fore of a rainless storm descended. Flashes of lightning lit up the whorls of air. In a dust storm, visibility plummets, but in exchange for common sight, you acquire uncommon vision. You can see the invisible, for the shape of the wind reveals itself. My mind’s image of that night is almost too vivid to be completely real — one of those recollections that has a question mark attached: Was it all true, all dream, or something in between? I’ll never know for sure. It is no accident that the most famous surrealist of the twentieth century had a special love for desert landscapes.[1] [3]

Dust storms usually happened a few times a year out there, but I never lost my sense of wonder at their rusty-red billowing and ominous approach. It was biblical. Bicyclists who rode into the gales seeking shelter, peddle as furiously as they might, never went anywhere; bike and rider toppled sideways. One minute doors could become impossible to open, and the next, violently insistent on it. But in that other lifetime, the most sublime occasion that I recall was a calm one. I was working a part-time summer job at the university library that day (down in the bowels of the building, where we kept journals and old microfiche slides, the latter used only by those familiar with the arcane arts). Around 2 PM a co-worker beckoned us upstairs with the promise of seeing something marvelous. We followed until we came to the building’s first-story wall of glass doors. There, we watched the rain coming down in beautiful sheets, and it sounded like heaven, too. All of us stood there for a long, blissful while, and mostly in silence. It was an event. People who have lived all their lives in temperate, greener places can imagine, but never truly understand the wonder that comes over a desert-dweller when the showers come down. It is mystical and viscerally religious. There is a God, readers, and He is in the desert rain.

This essay is about those dry zones that have inspired the Western imagination. A few years ago I wrote a piece on geography and its three “lifeways” that I called Port, Plain, and Mountain. I left out an important geographical archetype: the Badland. If we include both arid and semi-arid climates, these places account for over half the Earth’s landed area. The green, water-rich European peninsula doesn’t have many hot deserts;[2] [4] whites have encountered them elsewhere as explorers, travelers, traders, imperialists, and settlers — sometimes of the purely fantastic variety. The exception to this rule are areas of Spain’s brittle-baked region of Andalucía. Movie directors filmed plenty of 1950s and ‘60s Spaghetti Westerns (and films that required epic battle scenes, such as Laurence Olivier’s Richard III — Bosworth Field looked rather suntanned[3] [5]) near this part of the world, taking advantage of Spain’s lower production costs. So, chances are you’ve seen this semi-arid landscape before. Its name derives from al-Andalus, or what the Moorish invaders called their ever-shrinking patch of southern territory. I prefer to think of its name as coming from the Spanish anda en luz, or “walk in light.” Indeed, the primary color in summery Andalucía is yellow, yellow everywhere, from its golden plains of wheat to the jagged rises of the Sierra Alhamilla. The “Spanish-style” architecture of my college town pays homage to this Mediterranean dryland, and is why I will always have a soft spot in my heart for Spain.

Deserts place people in the surreal position of having to embrace a rugged self-reliance, while it also reduces them to the role of supplicants, for they find themselves at the mercy of the gods and their elements. There are plenty of vultures and carrion crows in more hospitable climes, but in the desert they are a hundred times more visible. It wouldn’t take long, one realizes, for these grotesque creatures to pick him clean to the bone, should he succumb to the desert’s harshness. There, Mother Nature’s heart is as hardened as her cracked and blistered ground; as pitiless as her heat from the boiling Sun. It is a masculine realm: lean, hard, and with no room for weakness. And yet, so many have been utterly seduced by it, as if fallen under the spell of an alluring dancer, or snake charmer. There are no places on Earth where one can see in all directions so well; no places on Earth with clearer skies. Yet, for all that clarity, what one sees might be a trick — a mirage as dangerous as any water-bound siren.

[6]

[6]You can buy And Time Rolls On: The Savitri Devi Interviews here. [7]

The act of clarifying one’s terms and providing explicit definitions for them are essential in any essay, just as a good theoretician or philosopher must begin by listing his assumptions. These practices are what separate the thoughtful of good faith from the stupid or malign, who seek to cloak their ignorance and/or malice behind semantic smoke and mirrors. Defining the meaning of “desert” might not seem like a high-stakes enterprise, but there are long-running disagreements and gray areas that geographers and climatologists have debated when it comes to these terms. Should we consider the frozen tundras near the poles “deserts?” What about the transitional areas that might also fall into categories such as “veldt,” or “grassland?” Can mountaintops be deserts? Islands in the middle of the ocean? The bottom of the ocean? Alien planets? Outer space, itself?

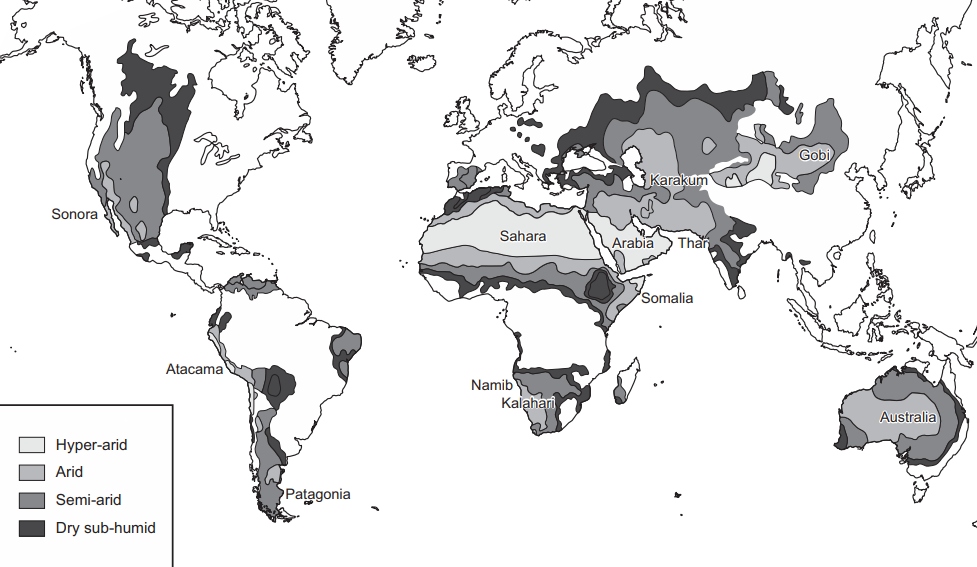

Since this article explores the historical and psychological understandings we have attached to desolate places, rather than a precise meaning of “desert,” I have chosen to take a broad view of the matter. Deserts are areas where water is the limiting resource. That is my only stipulation. Water lost through evaporation or transpiration exceeds that supplied from precipitation. How thirsty is the air? If someone were to place a bucket outside to catch the rainfall, and then noticed that it never (or very rarely) filled up, he could safely conclude that he lived in a desert. Desert landforms are eolian — a beautiful word that describes geology shaped primarily by wind, rather than water. Australia, because it is the oldest continent (a relative lack of geologic activity has rendered much of its soil barren), is mostly desertified. I consider the northern and southern tundras to be a kind of desert; these places support comparatively little in the way of life, and precipitation is not very common. Deserts can be hot, or cold, but all have stark differences between temperature highs during the day, and lows at night. Earth’s largest hot desert is the Sahara (with an area of 5,600 square miles). Its oldest may be the cool Atacama, stretching down the backbone of South America.

Earth’s cold deserts include the Gobi; parts of Greenland and Siberia; the Great Basin laid out across the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada Mountains; South America’s Atacama; areas in the vast, dry steppes of Central Asia; and the deadly Taklamakan Desert (meaning “place of no return”) that Marco Polo crossed in the thirteenth century. As for the extreme polar regions, Antarctica is one giant desert that happens to be frozen. A bleak landscape covers most of the continent, which is carved by wind and covered in glaciated mountain ranges. It occasionally rains along its coasts, but in some depressions of eastern Antarctica, scientists have estimated that no precipitation has fallen for 14 million years. Barring interplanetary travel, hiking the South Pole’s McMurdo Valley is as close to visiting Mars as an earthling will get.

[8]

[8]Earth’s deserts and semi-deserts, not including the tundras, or polar deserts; taken from Nick Middleton’s Deserts: A Very Short Introduction (2009).

Using this expansive definition, I include outer space. Like terrestrial deserts, the “vacuum” of space is shaped by invisible “winds,” or forces — the “stellar wind” cleared out our local neighborhood billions of years ago, allowing our solar system to develop in relative peace and quiet. Tidal waves, like gravity, also shape the universe, while other mysterious forces cinch and stretch the fabric of spacetime. On our graphing models these tortured ridges would look like gorges, canyons, and tracts of smoother, glassy plains. Our lovely blue jewel of a planet is an oasis amid the Creator’s black and cosmic sweep. Astronomers claim they have found interstellar ice-water clouds floating in suspended animation — other oases dotting the universe. According to the spectacular sensitivity of a Caltech spectrometer (“Z-spec”), there floated a huge cloud of water vapor tens of billions of miles away in a quasar galaxy.[4] [9] Apparently containing 140 trillion times the amount of water that exists here on Earth, this giant space-nimbus heated up because of the quasar’s extreme radiation bath.[5] [10] So, best not to drink it, no matter how parched you may be during your travels through uncharted space deserts.

Armed with these understandings, this article explores several desert themes: desolated wastes and plentiful oases; monsters and messiahs; conquest and disaster; ancient ruins and arrivistes. They are landscapes of rational, geometrical lines that have revealed our best geological data and fossilized phenomena, while they are also the scenes of the irrational — surrealist fantasies and, at times, fanaticism. Deserts were in the background — and sometimes the foreground — of the most dramatic legends of all time, for the desert deals in the primal extremes, not the betweens, of victory and defeat, exile and celebrated return, death and immortality. Gods and heroes wandered the “wilderness” (archaically used to mean “desert,” or barren place) to prove themselves through a series of tests. Perhaps they needed a talisman from afar, or knowledge of some esoterica. In the desert, gods were still gods, kings still kings, but they were also very human. They bled there as anyone would, and sometimes they failed in their errand. To make an extended soliloquy short: Deserts have always been frontiers of mind and places where almost anything could happen.

I. Deserts are the Source of Ruin and Fortune

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said — “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert . . .

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

— Percy B. Shelley, “Ozymandias [12]”

Why do we enjoy ruins? They summon past glories and more interesting times, when men were manly, women were beautiful, and we were better at making magnificent things. The ruin’s undeniable appeal lies in its blend of building and nature, the remnants of a tower or archway now carpeted in moss and wrapped in weeds and wild vines. Ruins are place, but also time, condensing past, present, and future into one spot: As we gaze at a fallen monument, we know that someone prized this structure. What happened to him and his world that caused its abandonment? We know, too, that such a derelict fate awaits us, when we will only be known by the things we leave behind. For the introvert there is another bonus: Ruins, by their definition, have long been deserted and thus are usually quiet. They are perfect places to indulge in the mesmeric drug of melancholy, while reading old classics against a broken pillar, or statue. All landscapes can boast ruins like these, but the desert ruin is especially stark, given its surrounding desolation. There, one feels truly alone and exposed — bare to the elements. Few plants will have reclaimed what ruins remain in the desert, but nature takes her toll nevertheless. The wind is their only adornment, and it is cruel enough.

We usually interpret Percy B. Shelley’s “Ozymandias” as a half-mocking, half-awed sonnet about the ephemerality of the ruin, rather than its timelessness. A passerby gazes at a pile of rocks; at what is left of Ozymandias,[6] [13] “King of Kings.” That largeness, that descriptor, makes his “Wreck” all the more ironic — a stand-in for countless other ruins that lie shattered and nameless in the desert. How the “Mighty” have fallen! This is one reaction to ruins. But the reason the poem has retained its popularity is not because of the irony. The Desert Ruin is the Great Man standing athwart the sands of time. He is the archetypal builder of “Works” with the face of a “Wreck,” the ancient monument beside an up-and-coming “traveler,” the two combining in one image the Knight reaching for a Relic. It never fails to tug on a chord deep within us and to play on those strings with lyrics our souls recognize: “My name is Ozymandias.” He was then, and I am now, and we are One, and our fates are somehow tied.

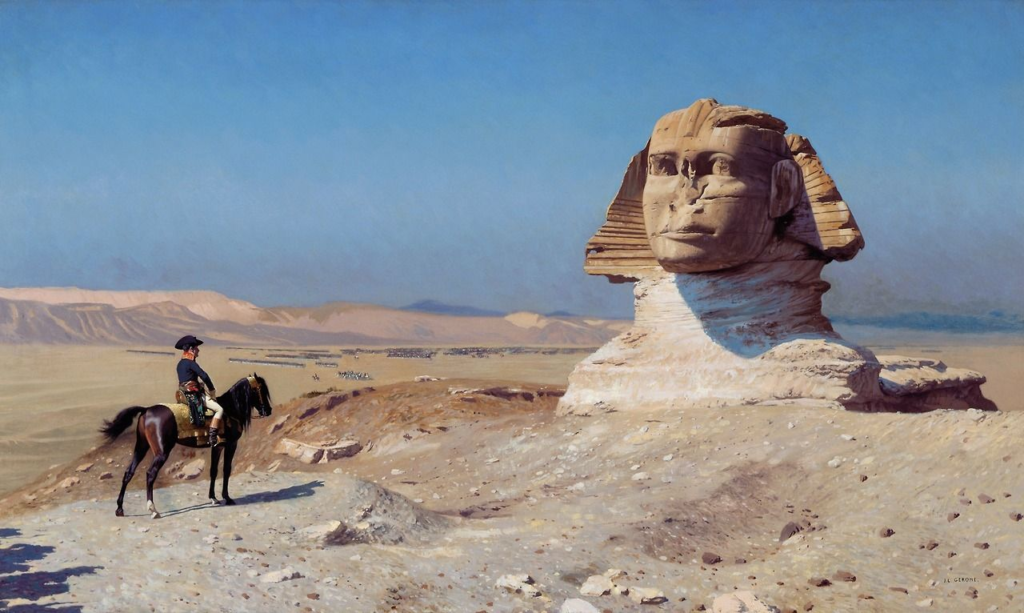

A newspaper published Shelley’s poem a few years after Napoleon’s famous expedition to Egypt in 1798. When the French general came face-to-face with the Sphinx and pyramids, he felt inspired, not mocking. These desiccated monuments in memory of god-kings vindicated him as a Westerner. The Occident had chosen the right path. The French, not the ignorant natives, were the true descendants of the pharaohs; the natives, not the grandly-columned temples and tombs, had deteriorated.[7] [14] The Napoleonic Era was the golden age of the Ruin, particularly the Desert Ruin, as Europeans began to go in search of ancient Mediterranean civilizations that lay at the foundation of their modern, “enlightened” civilizations. Archaeology and empire were interesting mixtures of the romantic and rational: How thrilling to come face to face with Agamemnon, or Ozymandias; how rewarding to uncover and decipher the secrets of history and science, and then build museums — the new churches — to house these far-flung treasures at home!

[15]

[15]You can buy Greg Johnson’s From Plato to Postmodernism here [16]

Europeans of this era knew that the Egyptian desert was home to ruins left behind by an ancient civilization that was far older than the more familiar Greeks, but their knowledge of who these people were was scant — reliant on Classical sources and the Bible. They had no idea how extensive those monuments were beyond the cities of Alexandria, Memphis, Rosetta, and Thebes. Before Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition, no one could decipher the hieroglyphics etched on tomb walls and tablets.

In the early 1780s, Frenchman Constantin-François Volney — having come into an inheritance — decided to tour Egypt and Syria[8] [17] with the ultimate aim of writing a travel memoir (which, along with captivity and shipwreck narratives, were fuel for bestsellers). It wouldn’t be one suffused with romanticism, or “sallies of the imagination,” Volney promised. For the most part, he kept his word. Volney’s Travels through Syria and Egypt was unsentimental.[9] [18] One could easily be seduced by his first, unsure steps in Alexandria, for instance, with its “spreading palm trees; the terraced houses that seem[ed] to have no roof; the lofty slender minarets that all announce[d] to the traveler that he [was] in another world.” Only after his piqued senses calmed would he take note of the “barbarous, guttural” noise that was the native language; the “meager and swarthy” inhabitants who bore all the marks of long oppression and misery; the wandering, mostly overweight “phantoms, which under a long drapery of a single piece, [a person will] discover nothing but two eyes [that] shew that they are women.”[10] [19]

Finding little to impress him in this glut of people, Volney found his “whole attention . . . attracted by those vast ruins which appear[ed] on the land side of the city.” In Europe, decayed castles announced “the desertion of [their] master[s], rather [than] the wretchedness of the neighbourhood.” On the contrary, in Alexandria they were “astonished at the immense extent of ground overspread with ruins.” The earth was “covered with the remains of lofty buildings destroyed, whole fronts crumbled down, roofs fallen in, battlements decayed . . . and disfigured by saltpeter.” As the traveler walked, he “passe[d] through a vast plain, furrowed with trenches, pierced by wells, divided by walls in ruins, covered over with ancient columns . . . where no living creature [was] to be met with, but owls, bats, and jackalls.” While the natives seemed unaffected by these scenes, the sight revived the European stranger, “in whom the recollection of ancient ages” welled up and overcame him. It was a sensation that could reduce him to tears, this combined effect of the ruins’ sadness and sublimity. Why did the residents of Alexandria not repair the port, or do anything that might elevate their baseness next to all this ancient majesty? “The answer,” Volney argued, is that “in Turk[ish lands] they destroy[ed] everything and repair[ed] nothing . . . the spirit of the government [was] to ruin the labours of past ages and destroy the hopes of future times, because the barbarity of ignorant despotism never considers tomorrow.”[11] [20]

The “despots” controlling 1790s Egypt were a peculiar group called the Mamluks, “Mamluk” being a term that meant “enslaved,” for most of them were non-Arab Caucasians who had been captured at an early age, then sold and gifted to various princes and pashas of the greater Ottoman Empire. These were no field hands, but men educated at wealthy courts and trained in the martial arts. Their masters and former masters then assigned them high-ranking positions in administrative government and the army. By the late eighteenth century, the elite Mamluks, like Ali Bey of Egypt, had slipped their leashes and become their own authorities amid the territories they oversaw. Ali Bey in turn controlled a knightly class of fellow-Mamluks that operated in a fashion similar to that of the European Cossacks. Indeed, these Egyptian horsemen originated from the same places as their Christian brethren: from the Balkans, Ukraine, Russia, Georgia, and other areas near the Black Sea. The local Egyptian population disliked them. The Mamluk armies, Volney observed, were “nothing but a confused multitude of horsemen, without uniforms, on horses of all sizes and colors, riding without keeping ranks, or observing any regular order.”[12] [21] Their power lay in their menacing aspect and intimidating show of sashes, sabers, and horseflesh. In other words, they relied on kicking up lots of dust, and little else. They were warriors, not soldiers — peacocks whom a well-trained European force would scatter like the fragments of sandy desert rock crushed beneath a boot.

At the same time that he criticized the people of Egypt, Volney teased an alluring potential of the desert: “If Egypt fell into the hands of a nation interested in culture, it would yield material to further our knowledge of antiquity such as can be found nowhere else in the world.” Though the ruins in the Delta were mostly destroyed, some monuments in the interior region of Upper Egypt and along the margins of the desert remained intact. “They are buried in the sand,” the memoirist claimed, “stored ready for future generations to discover.”[13] [22] Show me a prince who has not been seduced by the prospect of a treasure hunt.

By the turn of the nineteenth century, the British and French had been at war for several years, and an eager young officer had lately proved his mettle by driving the Redcoats out of the port of Toulon and away from the coastline of the French Riviera. He then wanted to strike an offensive, but an invasion of Britain itself was not realistic, so Napoleon did the next best thing. The British grew paranoid every time someone so much as glanced in the general direction of India, and Napoleon intended to do more than make eyes at the Orient. He intended to cut off his rivals’ primary route to their precious Subcontinent. With Volney’s travel guide tucked under his arm, Napoleon marshaled just such a force — his troops, seasoned and high off his victories in Italy — to steal Egypt from Ali Bey and his Mamluks. Volney’s text was the one thing in Egypt, French General Louis-Alexandre Berthier wryly remarked, that “never led [them] astray.”[14] [23] Following in the footsteps of Alexander and Caesar, Napoleon invaded Egypt.

As a young man, Napoleon Bonaparte had not dreamed of conquering Europe; he dreamed of an Eastern empire. “I must go to the Orient,” he declared, for “all great glory comes from there.” His Egyptian Expedition of 1798 remains one of the most romantic interludes in modern Western history. Most scholars of “Napoleonica” stress the General’s ruthless pragmatism, but Napoleon was a child of the Romantic and Neoclassical movements that swept Europe in the late eighteenth century. These idealistic intellectual currents resulted in an enthusiasm for rediscovering Western Civilization’s mythical origins; for celebrating great men who accomplished great things. Old ruins were all the rage, even as the Enlightenment removed Westerners further and further from a rooted past. And what landscape appeared somehow more ancient and mysterious than all others? The desert, of course, with its seemingly eternal changelessness, even as it shifted in unceasing waves of quicksilver sand.

Filled with “tally-ho!” Enlightenment esprit de corps, Napoleon brought with him 170 hand-picked savants (experts in archaeology, engineering, astronomy, chemistry, even poetry) to accompany the French army as it sailed toward the Egyptian coast. Aboard Napoleon’s flagship, L’Orient, he gathered together the cream of this intellectual group for nightly seminars. They discussed great scientific and philosophical questions, such as: “Is there life on other planets? What will bring about the end of the world? How old is the Earth?” Though Napoleon insisted on being treated as an equal during these stimulating pow-wows, “his voice stilled all others.”[15] [24] Indeed, Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign would mark the beginning of his astonishing ascent to power, while it also ushered in the great age of imperial archaeology.

[25]

[25]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Graduate School with Heidegger here [26]

As his armada neared the North African coast, Napoleon glimpsed his first desert ruin. It was the solitary remnant of Pompey’s Pillar that marked the once-great city of Alexandria. In the third century BC, there stood one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World: a 400-foot-tall lighthouse called the “Pharos of Alexandria.” Aided by a mirror, its light cast a beam that sailors could see up to 80 miles away. It had long since crumbled into an equally dilapidated harbor. At dawn on June 30, Napoleon, his beloved Army of Italy, and his team of savant-chroniclers made berth near the port of Alexandria. They also made short work of any resistance and entered the city, where they met a bemused population.

Upon securing Alexandria and Rosetta, Napoleon marched his army south into the desert and toward the ultimate prize of Cairo. Archaeologist Vivant Denon noted that a mere hour after walking through cultivated land, the entourage “entered mountains composed of crumbling slate, sandstone, white and rose-colored quartz, brown pebbles and a few pieces of white coral.” After four more hours of this, “boots [were] torn to pieces . . . [the men] were devoured by raging thirst.” He soon realized that the desert — not Mamluk fanatics — was the greatest enemy. In the 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia, a journalist asked Peter O’Toole’s Lawrence what he most liked about the desert. “It is clean,” was his terse reply — not the glamorous response the correspondent was hoping for. While this may be true of some deserts (fewer people, less filth), it was not the case in 1798 Egypt. Among other nasty torments, eye infections proliferated. The cause was poor hygiene and atrocious, mountainous “local rubbish heaps, exacerbated by wind, sand,” and tiny flecks of straw.[16] [27] Men cried tears of pus. European soldiers accustomed to the rivers and verdant forests of France found the journey intolerable, while their wagons and cannon continually sank into the soft, golden sand.

Besides Napoleon, the savants were the only ones who wanted to be there. But many soldiers did occasionally get into the spirit of things, one corporal recalling that he “inscribed [his] name, [his] place of birth, [his] rank . . . in the royal chamber, on the right of [a] sarcophagus.”[17] [28] At the time these actions weren’t widely considered to be vandalism, and the myth that French soldiers shot off the Sphinx’s nose was a calumny (possibly spread by the British). Muslim iconoclasts of earlier centuries were in fact to blame. Napoleon and the French could only speculate about the Sphinx’s true dimensions; over the course of tens of centuries, the sand had buried it up to the monument’s neck.

The party began to sense “that they were approaching the limits of the known world.” Before their eyes, everything took on a mysterious quality. The “distant Nile would ripple and then appear to evaporate in the heat haze,” while small “clusters of huts would suddenly appear and then disappear on the far shore of the mirage lakes which shimmered out in the desert.” At Tentyra they found a temple of giants; at Thebes, once described by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus as “the city of a hundred gates,” troops and savants alike broke out into spontaneous applause and began to pound their military drums. The complementing image of Europeans, bedecked in modern dress and formation, with that of antiquity’s vast, sweeping remains caused Denon to experience a surge of patriotism:

The feelings . . . in the presence of such great monuments, and the electrifying sight of an army of soldiers of such civilized sensibility, made me overjoyed to be their companion, and rejoice in being French.[18] [29]

In their minds, Egyptian ruins had somehow become French, the French having “liberated” them from their obscurity. General Louis Desaix wrote to Napoleon of two obelisks found near Thebes. “Transported to Paris,” he enthused, “they would cause a sensation!”[19] [30] At Rosetta, a savant excavated an even more exciting find — a tablet with a passage written in three languages: Greek, Arabic, and ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. It was the key necessary to decode the picture-words they found on tomb walls and scrawled across columns. Its discovery heralded the beginning of Napoleon’s L’Institut de l’Egypte.

Finally, on July 21, 1798 near the banks of the Nile River, Napoleon reached Cairo and the Mamluks who defended the capital. Before the engagement that history would remember as the Battle of the Pyramids, Napoleon addressed his troops. Silhouetted in front of Giza, he appealed to them: “Soldiers! From atop the pyramids, 40 centuries of history bear witness to you.” The pharaohs of old, he had turned into French gods of benediction. He ordered his 20,000-man army to form three giant squares (baggage and supplies in the middle) against which some 40-60,000 mounted Mamluks and peasant infantry dashed themselves like splintering ships on the shoals. The young commander lost only 20 men and completely routed the Mamluks and their fellahin supporters. The fleeing enemy had no choice but to throw themselves into the silt-blackened waters of the Nile. A few managed to survive the crossing, but most became fodder for the crocodiles. Napoleon’s Army of the Orient proceeded triumphantly into Cairo. It was the high point of a campaign doomed to collapse.

Meanwhile, all of scholarly Europe was abuzz with the savants’ astounding finds. One of the very first terms that European code-breakers and archaeologists translated after “cracking” the Rosetta Stone was a glyph on an Egyptian artifact, tésert, its literal meaning being to forsake, as one would an old wreck. It was the ancient Egyptian word for “desert.”

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

Due to an ongoing cyber attack [31] from those who disagree with our political discourse, our Green Money echeck services are temporarily down. We are working to get it restored as soon as possible. In the meantime, we welcome your orders and gifts via:

- Entropy: click here [32] and select “send paid chat” (please add 15% to cover credit card processing fees)

- Check, Cash, or Money Order to Counter-Currents Publishing, PO Box 22638, San Francisco, CA 94122

- Contact [email protected] [33] for bank transfer information

Thank you for your support!

For other ways to donate, click here [34].

Notes

[1] [35] Salvador Dalí.

[2] [36] Europe does have hot, drier climates in countries that border the Mediterranean, and on islands surrounded by that lovely sea, but for the most part these would not qualify as deserts.

[3] [37] Olivier, as director and leading man, chose “those stunted Spanish trees and the silver grass” near the Madrid environs (not Andalucía), partly because they showcased the film’s battle sequence to epic effect. It is a landscape of destiny.

[4] [38] According to the latest theories, quasars were ancient active galactic nuclei with large black holes at their centers that emitted tremendous amounts of radiation — so much energy that even though they are among the most distant things in the visible universe, these quasars still shine brightly through our space telescopes, like the Hubble and James Webb Infrared. The nearest quasar is thought to be 600 million light years away, and most are much further from us.

[5] [39] “Scientists Have Found More Water in Space Than They Ever Thought Possible [40],” January 20, 2021.

[6] [41] “Ozymandias” is the ancient Greek equivalent of “Ramasses.”

[7] [42] For Napoleon there existed only two types of peoples worth mentioning: Occidentals and Orientals.

[8] [43] Europeans used “Syria” to mean the entire Levant during the period.

[9] [44] As this era marked the very beginnings of Egyptology, Volney’s memoir made some inaccurate hypotheses, one being that the ancient Egyptians were “negroes,” based on his limited sightseeing of some ruins along the Nile. To him, the somewhat thicker lips and flatter noses of these stylized statues (most of which had long since been sheared off or defaced, leaving them with a “flattened” look) proved they were based on black physiognomy and explained why their later descendants, who had supposedly mixed with lighter-skinned peoples, looked “exactly” like “our mulattos.” Afro-centrists have taken this preliminary guess and used it as solid proof that ancient Egypt was a black civilization. We know that they were Mediterranean people, and DNA testing has confirmed that they would have looked similar to present-day Caucasians who live near that sea.

[10] [45] Constantin-François Volney, Travels through Syria and Egypt, in the Years 1783, 1784, and 1785, Vol. I (London: C. G. J. & J. Robinson, 1838), vi, 3, 4.

[11] [46] Ibid., 5, 6.

[12] [47] Ibid., 125.

[13] [48] Ibid, 285.

[14] [49] Paul Strathern, Napoleon in Egypt (New York: Bantam Dell, 2007), 30.

[15] [50] Ibid, 16.

[16] [51] Vivant Denon, Voyages de la Basse et la Haute Égypte pendant les campagnes de Bonaparte, Vol. I, 198, 215-216.

[17] [52] Strathern, 283.

[18] [53] Denon, 186.

[19] [54] Strathern, 385.