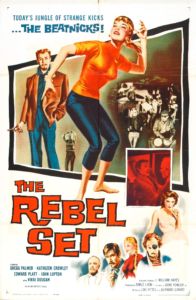

Breaking Beat: Reflections on The Rebel Set, a Masterpiece That Never Was

Posted By James J. O'Meara On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledThe Rebel Set

Directed by Gene Fowler, Jr.

Starring Don Sullivan, Gregg Palmer, Kathleen Crowley, Edward Platt, Ned Glass, & John Lupton

Written by Bernard Girard & Louis Vittes

Cinematography: Karl Struss

Edited by William Austin

Music by Paul Dunlap

Allied Artists, 1959

The question is not infrequently asked: why do you bother watching “bad” movies.? I’ve given somewhat theoretical answers before,[1] [2] but this movie (or rather, film!) — 1959’s The Rebel Set — provides a simpler answer: It’s fun!

B-GUYS! (The Beatnicks [sic]) Living and Loving for strange kicks!

JET DOLLS! Ready and willing to go into orbit!

KING OF BEATSVILLE! Mastermind behind a million dollars’ worth of murder!

THE “WEIRDIES”! Nobody knows what makes them tick!

I don’t know about you, but sign me up!

Hollywood of course exploited — and some might argue, created[2] [3] — the beatniks (vide The Beatniks [4][3] [5]). This is a relatively late entry, but it really makes the most of its subculture, at least to start with. As TVTropes notes, “Beatniks [6]: The early scenes are set in a bar full of them.”[4] [7]

Of course, since this is a Hollywood production, this is mostly bullshit — or as one beatnik says, just so much “chopper music but no tune.”[5] [8] The beat scene is fairly well outlined, with a crowded late-night coffeehouse that is apparently real,[6] [9] poetry readings from a resident beardo-weirdo [10] (“Stew oceans of lotion on the beards of each man!”), [7] [11] some pretty cool jazz music, even a party at a lousy cold water flat with a black-clad chick out of a Jules Feiffer cartoon doing interpretive dancing [12] — but it’s only there for the first half hour or so, and only to provide us with the beatniks — or rather, losers — who will be used as cannon fodder for the master criminal’s master plan.

Said master is Tucker — or “Mister T,” as he’s referred to on occasion, to the amusement of any viewer who was around in the ‘80s[8] [13] — who himself is only pretending to be the “hip” owner of a beatnik dive (“When in Rome, do the Romans” he explains to the puzzled Sydney, who remains puzzled, along with the audience), while his sidekick/henchman Sidney makes no pretense of being anything but a vaguely Jewish, vaguely Brooklynese two-bit con man who holds the beats in contempt. Asked by Tucker “Are you beat?”, Sydney snarks, “Oh, sure, man, cool, way out and long gone, dad, as they say,” a line that I’ve used myself on occasion.[9] [14]

Why the pretense? Mr. T is the man with the plan, and it’s a great example of what TVTropes calls the Batman Gambit [15]:

Tucker clearly considers himself a master of this. He chooses for his accomplices people who are known to be desperate, this way he can easily turn them on each other if they don’t turn on each other first, and he’s chosen people who he is confident are competent enough to follow his plan but not enough to successfully betray him.[10] [16] Even if there are any left standing at the end, he has crafted himself a reputation as an eccentric but otherwise upright business owner.[11] [17]

Well, that’s more of a rational reconstruction, with little basis in the movie.[12] [18] What Tucker tells Sidney (whose role in the movie, if not in the plan, is to serve as the uncomprehending recipient of Tucker’s bon mots[13] [19]) is that these losers, who Sidney calls “creeps,” when given one last chance to redeem themselves will move with steely determination beyond anything you could expect from mere hired hands.

I’m not buying it, and the plan works out as badly as you’d expect.

It’s interesting that the movie itself postulates that beatniks, or at least some portion of them, are themselves, as Holden Caulfield would say [20], phonies; as Tucker reveals his plan, Bond-villain style,[14] [21] to the chosen ones, he starts off with this beat-down: “You’re not Beat, you’re merely beaten; you’re not detached, you’re unemployed! You’re not dispassionate, you’re afraid.”

But enough chopper music, what is this movie about? Wikipedia sets the scene [22], daddy-o:

Mr. Tucker (Platt), proprietor of a Los Angeles coffee house, hires three down-on-their-luck classic beatnik patrons: out-of-work actor John Mapes (Palmer); struggling writer Ray Miller (Lupton); and George Leland (Sullivan), the wayward son of movie star Rita Leland, to participate in an armored car robbery to take place during a four-hour stopover in Chicago during the trio’s train trip from Los Angeles to New York. Mapes’ worried wife Jeanne (Crowley) joins him on the train, concerned about his not having had a job in more than a year.

The rest goes into spoiler territory — and you will want to see this film — so let TVTropes [23] tie things up:

Three down-on-their-luck beatniks — John Mapes, an aspiring actor; Ray Miller, a failed writer; and “poor little rich boy” George Leland, the neglected son of a famous movie star — are hired by an amoral coffee house proprietor [!] to help pull off an armored car robbery during a rail trip. The heist goes off swimmingly; but afterward, on the train to New York, the conspirators begin dying, one by one.

At this point I should reveal that a large part of the entertainment here is that this is what might be called a spectral film in that the shades of many other films, past and even some not yet made at the time, flit through it. Along the way, one can’t help but imagine how this film might have turned out if given the same chances. Although true of many films, it’s especially true here, and more than makes up for any B-movie flaws.

[24]

[24]You can buy James J. O’Meara’s Passing the Buck: Coleman Francis & Other Cinematic Metaphysicians here [25].

Tucker is played by Ed Platt, most recognizable today as “The Chief” on Get Smart (a fact to which the Mystery Science Theater (MST) crew make frequent reference),[15] [26] while his henchman, Sidney, is played by Ned Glass, who is recognizable from dozens of minor parts in B movies and TV.[16] [27]

That very same year, Platt and Glass would each appear in bit parts in a rather grander film: Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. Platt plays Cary Grant’s unnamed lawyer, while Glass is the nosy guy at the ticket booth in Grand Central. Given the odd effect of their major roles in this minor film against their minor roles in a major film the same year, it kind of resembles a version of Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

With that in mind, one can see The Rebel Set as a kind of dry run for Hitchcock’s film. The trip from Los Angeles to Chicago is mostly elided to get to Chicago and the heist, so in effect it’s the first half of North by Northwest, reversed: a train trip, with a surprise woman, from Chicago to New York, with Platt and Glass then jumping on at Grand Central and taking over the movie.

Keeping with the North by Northwest connection, Gregg Palmer was supposed to be the next Rock Hudson — he even appeared in Hudson’s “breakthrough” film, Magnificent Obsession (1954) — but it never happened, for a number of reasons, including bulking up to 300 pounds, which, combined with his six-foot-and-four-inches stature, led to his being typecast not as a romantic lead but as the “menacing brute” in innumerable TV and movie Westerns, including several John Wayne films.[17] [28] I suppose if you squint the right way, you can see him as a discount Cary Grant, while the blonde wife he decides to bring along would be Eva Marie Saint. Maybe.

Another fun part of “bad” movies is the occasional unexpected standout performance, the “sapphire in the mud.”

Glass and Platt give competent performances, as one would expect from their extensive careers before and after. The real standout here, though, is Don Sullivan, who also appeared in another MST’d film from 1959, The Giant Gila Monster, but soon left Hollywood. Based on his interviews in the MST special features for Gila Monster, he seems like a really nice guy, and was still pretty handsome.[18] [29]

More to the point, he delivers a great performance in a small role (he’s the first one Tucker kills off, intending to frame the others), and especially in a scene he shouldn’t be in [30]. It’s the punchline to an “anvil joke” set up right from the first scene: Sydney is a busted watch salesman and has a thing for the waitress, “Miss IQ.”[19] [31] I say he shouldn’t be in the scene because he has nothing to say and nothing to do; this is a blunder on the director’s part.[20] [32] Yet this is one of those wonderful moments to be found in B movies: Don is, as actors say, really in the scene; he’s right there with the others, not biding his time until someone yells “cut.” As the others pass the watch around and finally figure out that “dear Sydney” scammed her on his way out of town, everything registers on his face or in his posture or gestures. It should be a film school classic.[21] [33]

As the first to be killed, his screen time is otherwise relatively short; he’s there only because this “spoiled little rich kid” was sent to military school, where he proved to be “the best shot [Tucker] knows.” The misfit who proves an unlikely sharpshooter and names his rifle “Betsy” recalls Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (and the film itself seems to be hoping to cash in on the “heist film” craze kicked off by Kubrick’s equally low-budget The Killing from 1956[22] [34]).

One wishes the movie were better known, or at least had a substantial cult, since I’ve come up with what I modestly think is a rather clever twist: What if Tucker isn’t (just) a master criminal, posing first as a coffee shop owner and then as a priest, but was always a priest — “the Reverend Basil Cunningham, or is it Very Reverend?” This would explain his command of misapplied or manufactured quotes and sermonic bromides.[23] [35]

“When in Rome, do the Romans.”

“A rose by any other name . . . would still have thorns.”

“Thus did mighty Samson overcome the Philistine.”

“How many men are afraid of ghosts, who are not afraid of the All-High?”

“The alpha and omega of my psychology of crime.”

His smug introduction of his clerical persona on the train — “The Reverend . . . or is it Very Reverend?” — is not a self-aware irony about choosing a phony identity, but reflects a previous, very serious clerical ambition that was somehow thwarted, leading him to turn his intellect to crime: breaking beat?[24] [36]

Tucker’s twisted ambition recalls Goldfinger:

Man has climbed Mount Everest. Gone to the bottom of the ocean. He has fired rockets at the Moon. Split the atom. Achieved miracles in every field of human endeavor . . . except crime!

It would have been clever to have Tucker sucked out of a train window somehow, or fall out like Uncle Charlie in Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, but as it is his fate also recalls Goldfinger: electrocuted by his sitting stick, like Oddjob and his metal hat.[25] [37]

[38]

[38]You can buy James J. O’Meara’s Mysticism After Modernism here [39].

To revert to our comparison of Tucker and Sidney to Burroughs and Huncke, it’s kinda like if respectable Burroughs had fully dropped into the criminal world rather than just exploiting it for his writing: “’The Priest,’ they called him [40].”[26] [41]

Speaking of writers, John Lupton, as the bad beat writer, is the weak link here. He makes so little impression that I had to scroll up to find his name, and I still don’t remember his character’s name.[27] [42] Rather than Tucker being sucked out the window, he throws Lupton off the train, but even that’s off screen. He gets one notable scene: The conductor (B legend Gene Roth [43]) comes in to punch his ticket, notices his typewriter (which, of course, will play a role in setting up another death as a suicide), and sits down to tell him about all “the stories” he could tell, if only he could type; then offers Lupton a 50/50 deal on them. Bored and offended, Lupton brushes him off. Here, another cinematic specter brushes by the viewer: the burly working-class guy “who could tell you some stories,” the supercilious but talentless writer, the typewriter: It all recalls John Goodman’s encounter with the titular Barton Fink.[28] [44]

Director Gene Fowler, Jr. previously directed such low-budget but beloved works as I Was a Teenage Werewolf and I Married a Monster from Outer Space, but he became better known as a film editor, including such major productions as It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World and Hang ‘Em High. In a way, that epitomizes this film’s situation: Like many a B picture, it could have been a contender with a bigger budget and bigger “stars.” Platt and Glass, as noted, give competent performances, Sullivan is a promising newcomer, and Roth adequate comic relief, but the rest of the gang leave little impression, and the script is all over the place: Is it a heist film, an exploitation film set in the Beat world, or a tragic romance?[29] [45]

Speaking of tragedy, there’s another odd element that’s either deliberate or a wonderful accident. When picking up what looks like a box of Krispy Kreme doughnuts for a Friday treat at the office — a large, rectangular box needed to hide the loot later — Sullivan (if it’s an accident) or his character (if it’s in the script) closes the car door, and the tail of his lighter-colored overcoat is caught and left hanging out; later, after the heist, he does the same thing.

Was the audience supposed to think this would betray them to the cops? Then, at the end of the film, as his corpse is being wheeled out of the train station in a makeshift coffin, there’s a dark cloth caught on the lid and hanging out. So was it supposed to mark him for death earlier? What about the writer, who’s also killed? And was it an oversight, or a mistake they decided to leave in, or was it in the script? More research is required, as they say in academic publications. Let the archives be opened![30] [46]

Perhaps the movie is confused because, as noted above, it’s one of the first heist films in the wake of Kubrick’s The Killing (1956). The final spectral aspect is that it leaves one imagining what it would look like given the lavish production and star power that would later produce Sinatra’s Ocean’s Eleven [47] (1960), itself remade in 2001 (Kubrick again!) as a vehicle for George Clooney, later becoming a franchise of its own.

The popularity of the heist film derives, I’ve argued, from its evocation of the ancient Aryan institution of the Männerbund. Of course, this is an example of what I’ve called the Bad Männerbund, like Al Capone’s mob or Captain Ahab’s crew.[31] [48]

As is so often the case, the version shown on MST3k (Season Four) has cuts that result in the film being more disjointed than is really the case. In the original cut, a long “cold open” shows us Sidney plying his trade, scamming marks for fake watches. This explains why, when we first meet him and Tucker, he’s reporting on his watch “sales.” The viewer might think he’s just selling bad watches (another character, a waitress, is later furious with him for selling hers) rather than running a rather elaborate scam on his victims. “Good hunting!” Tucker responds, when Sidney reports over $300 in “sales.” Indeed, based on the opening scene he would have had to scam over 12 people that night.

Another cut scene explains a major plot hole: what happened to Sidney after the robbery. We never see him again in the MST3k version.[32] [49]

The full, uncut film is on YouTube (here [50] and here [51]), but the print is so muddy it may be unwatchable if you haven’t already seen the MST3k episode; it fills in the cut scenes, but the MST version provides a memory that helps fill in the image onscreen. The cheap DVD is just as bad. This is a movie that cries out for a 4k Blu-ray restoration, and if that sounds nuts, may I call your attention to: Zaat [52] (another MST3k episode, under the title Blood Waters of Dr. Z), a fun but dumb — and far from spectral — movie that gets the full treatment which posterity owes The Rebel Set.

Over and out, daddy-O!

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [53].

Notes

[1] [54] Of course, in my collection, Passing the Buck: Coleman Francis & Other Cinematic Metaphysicians [55] (Colac, Victoria, Australia: Manticore Press, 2021). Basically, incompetent filmmakers (and screenwriters with “contempt” for the material; see my “Mike Hammer, Occult Dick: Kiss Me Deadly as Lovecraftian Tale [56],” reprinted in The Eldritch Evola . . . & Others [57]) leave plenty of room for other, more interesting things to slip in, while the boredom of the audience puts them in a ideally receptive mood. By contrast, the slick Hollywood professionals are usually just pushing the Narrative on you; beware when they take an interest in you, the viewer: “I don’t know what the hell you said to Lipnick, but the son of a bitch likes you. Do you understand that, Fink? He likes you! He’s taken an interest. Never make Lipnick like you. Never! (Barton Fink).

[2] [58] See Miles Mathis, “From Theosophy to the Beat Generation or How even the Occult was Disguised [59].”

[3] [60] Perversely, this film contains no actual beatniks, just the usual juvenile delinquents, but that just shows that the filmmakers were desperate to attach it to the trend, if only titularly; originally, it was Sideburns and Sympathy, which, believe it or not, is one of the “songs” featured therein, so I suppose Elvis was the original idea being exploited. Like the previous year’s The Rebel Set, it also got the MST3k treatment [61], for this and many other cinematic sins: “These beatniks are square, man.”

[4] [62] Akshully, it’s literally a coffeehouse, no booze. Mr. Tucker, the proprietor, even makes a point of this when serving soft drinks to his newly-drafted heist team: “I don’t believe in breaking small laws” (i.e., he has no liquor license). MST3k’s Servo tops his attempt at wit by adding, “There are no small laws, only small crooks.” TVTropes does get it right later, under Minor Crime Reveals Major Plot [63].

[5] [64] This puzzled me for a while, but I eventually figured out this is the untalented novelist character — or the screenwriter — showing off by riffing on the presumably Yiddish slang phrase “chin music,” choppers being teeth.

[6] [65] There’s even, I’m told, a real Rauschenberg or Rothko on the wall in the coffeehouse scenes, worth millions today.

[7] [66] With the great name “King Invader” (played by one I. Stanford Jolley). King, of course, is a rather usual name, and like Duke seems more common as a dog’s name. But it also seems more common in Hollywood, make of that what you will: There’s King Vidor, director of The Fountainhead, among other films; and Robert “King” Moody [67] was Schtarker in Get Smart, along with Ed Platt, as well as starting (or schtarting) his film career as the rather mature leader of the Teenagers from Outer Space (also 1959), another MST3k fave. Tor-chaa [68]!

[8] [69] Wikipedia reminds me [70] that, in addition to Rocky’s Mr. T [71], there was also Mr. T and Tina [72], starring Pat Morita, and even supposedly Maggie Thatcher’s husband.

[9] [73] Sydney is the “colorful” type of Broadway crook that William Burroughs liked to befriend in the 1940s, such as Herbert Huncke [74]. There’s a kind of Burroughs/Huncke vibe to the Tucker/Sydney relationship, with Tucker pontificating to Sydney’s bemusement. We’ll later explore the question of where this Tucker comes from. Sydney has the perverse work ethic of the working-class criminal (Burroughs describes one in Junky as needing to steal something every day to feel good about himself), proudly showing off the money he’s brought in with his busted watch scam: an “earner,” as the mob would say. Thus he feels contempt for the beatniks, referring to the three stooges Mr. T choses as “creeps,” just as “hard hats” hated the lazy hippies.

[10] [75] In The Departed (2006), Billy successfully allays Frank’s suspicions with an inversion of this:

Billy: The question is, who thinks that they would do what you do better than you?

Costello: Only one that can do what I do is me. You want to be me?

Billy: I probably could be you. I know that much. But I don’t want to be you.

[11] [76] Adding: “He even lampshades [77] this early in the movie when his lackey [Sidney] compliments his ability to play chess, and Tucker replies that he merely makes a point to play against people he knows are worse than him.”

[12] [78] It actually sounds like The Big Lebowski:

Jeffrey: You’d just met me . . . You figured, “Oh, here’s a loser. A deadbeat, someone the square community won’t give a shit about.”

Lebowski: Well, aren’t ya?

Jeffrey: [a pause] Well, yeah!

Not for the first time, as we’ll see, The Rebel Set acts as a strange attractor, drawing bits and pieces of other, better movies into its black hole.

[13] [79] “The Watson [80]: Sidney seems to be in the film mainly so Tucker can explain ‘the Alpha and the Omega’ of his evil genius.” (TVTropes)

[14] [81] A combination of Dare to Be Badass [82] and “The Reason You Suck” Speech [83]; for a canonical example, minus the suck, see Braveheart: “Every man dies, but not every man truly lives [84].”

[15] [85] “Edward Cuthbert Platt (February 14, 1916-March 19, 1974) was an American actor best known for his portrayal of the Chief [86] in the 1965–1970 NBC [87]/CBS [88] television [89] series: Get Smart [90]. With his deep voice and mature appearance, he played an eclectic mix of characters over the span of his career.” Wikipedia [91] adds a sad note: “On March 19, 1974, Platt was found dead in his Santa Monica apartment, at the age of 58. Initial reports indicated the cause of death was a heart attack, but Platt’s son later said that his father died from suicide, after a long struggle with untreated depression.”

[16] [92] “Nusyn ‘Ned’ Glass (April 1, 1906-June 15, 1984) was a Polish-born American character actor who appeared in more than eighty films and on television more than one hundred times, frequently playing nervous, cowardly, or deceitful characters. Short and bald, with a slight hunch to his shoulders, he was immediately recognizable by his distinct appearance, his nasal voice, and his pronounced New York City accent [93]. Notable roles he portrayed included Doc in West Side Story [94] (1961) and Gideon in Charade [95] (1963).” (Wikipedia [96]) Other online sources reveal that he “grew up in New York” [no kidding!] and that “[u]ntil the mid-1950s he was seen primarily in tiny supporting roles as clerks, reporters, bank tellers and small-time managers. His career was briefly put on hold after being blacklisted during the McCarthy era, but, with help from friends like John Houseman and Moe Howard (of The Three Stooges fame) he managed to get enough film work to make ends meet.” Paul Dunlap [97], who composed the remarkably authentic jazz score, would also work on several later Three Stooges films as well.

[17] [98] According to an Internet Movie Database reviewer: “He got slugged by the Duke in The Undefeated, pitchforked by the Duke in Big Jake [after he kills the Duke’s dog] and shot in the gut by the Duke in The Shootist.” See the career overview in “Gregg Palmer, Bad Guy in John Wayne’s ‘Big Jake,’ Dies at 88 [99].”

[18] [100] “Held a chemistry degree from the University of Idaho and, after leaving film acting, became one of the top creative cosmetic chemists in the hair industry.” Wikipedia.

[19] [101] Coney Island’s Vikki Dugan, who had a brief film career but was best known for backless dresses [102], dating Frank Sinatra, and pictorials in Cavalier and Playboy. Still alive and kicking at 94, according to Wikipedia [103] she “regularly attends the Los Angeles Jewish Film Festival.” There’s a persistent Internet claim that she inspired the Jessica Rabbit cartoon character [104], which in itself counts as more spectral content.

[20] [105] Or the screenwriters, Bernard Girard and Louis Vittes, both of whom seem to have had mediocre careers in B movies and TV; the IMDB entry on Girard even admits “the majority of his film output has been routine.” Vittes worked with director Fowler on the B fave I Married a Monster from Outer Space the previous year, which apparently earned him screen credit for the 1998 remake, although his last film was in 1969. He also worked on Rawhide and The Wild Wild West, so maybe he’s the guy who so impressed Walter in the same year’s The Big Lebowski.

[21] [106] Someone called my attention to this on the Internet, but I can’t recall whom. In Passing the Buck: Coleman Francis & Other Cinematic Metaphysicians (Colac, Victoria, Australia: Manticore Press, 2021), I discuss a similar revelatory moment in Francis’ The Skydivers, where Beth, who fears her husband, Harry, will leave her for the local rich floozy suddenly realizes that he’s become violently jealous of an innocent flirtation with his old friend Joe. Francis ends the scene, but lingers on Beth’s face, and wordlessly, the emotions of fear, puzzlement, relief, and joy wash across the actress, Kevin Casey. Francis being Francis, of course, he crudely ends the shot with one his trademark jump cuts.

[22] [107] Thanks to reviewer dougdoepke at IMDB.

[23] [108] TVTropes: “Sesquipedalian Loquaciousness [109]: Tucker is surpassingly eloquent. When confiding with his main man Sidney, his dialogue nearly degenerates into an Expospeak Gag [110].”

[24] [111] This would also account for what TVTropes calls his “Paper-Thin Disguise [112]: A clean shave and a priest’s collar is all Tucker apparently needs to disguise himself as a priest. The episode guide for the MST3K episode notes that the first time the MST3K crew watched the film, it took them all quite a while to realize it was supposed to be a disguise.”

[25] [113] I’ve honestly never seen or heard of such a thing, yet it exists [114]; the MST3k crew is also amazed and amused by it, so maybe it’s not a part of Great Lakes culture. Just as Goldfinger’s demise is lampshaded by Bond earlier advising Pussy Galore about the dangers of shooting a gun while airborne, the sitting stick plays an even more extensive role throughout the last half of The Rebel Set. Tucker uses it to set himself up to observe the robbery from a distance; during the disposal of the equipment, we think it’s going to be left behind to betray them, but he snaps it up at the last minute. In its final appearance, he uses it to knock out a cop so as to make his escape from the train. That’s where he makes his “thus did mighty Samson” remark, which puzzles the MST3k crew: “With a sitting stick?” But this is necessary to shift the device from being “a versatile product that simultaneously provides outdoor lovers with a seat for resting and a hiking stick for support.,” as Amazon says [115], into a weapon, thus completing the spectral foreshadowing of Oddjob’s snappy yet deadly hat.

[26] [116] Tucker is an interesting example of what Burroughs called “the setup man” in his first, most noir book, Junky: “This bar was a meeting place for 42nd Street hustlers, a peculiar breed of four-flushing, would-be criminals. They are always looking for a ‘setup man,’ someone to plan jobs and tell them exactly what to do. Since no ‘setup man’ would have anything to do with people so obviously inept, unlucky, and unsuccessful, they go on looking, fabricating preposterous lies about their big scores, cooling off as dishwashers, soda jerks, waiters, occasionally rolling a drunk or a timid queer, looking, always looking, for the ‘setup man’ with a big job who will say, ‘I’ve been watching you. You’re the man I need for this setup. Now listen . . .’” I suppose Sidney was originally one of those “42nd Street hustlers” who actually met such a setup man. But as we’ve seen, Tucker’s hubris leads him to formulate a literally perverse “philosophy of crime,” such that it’s precisely “people so obviously inept, unlucky, and unsuccessful” that he selects; and as we’ve seen, it goes about as well as Burroughs would have predicted.

[27] [117] His IMBD biography calls him [118] “a reliable actor, if not particularly distinctive, [who] enjoyed a four-decade-long career on stage, film and TV,” including a long stint on Days of Our Lives, but nothing memorable; the biography doesn’t even mention The Rebel Set.

[28] [119] Although the MST3k crew make a memorable skit and running gag about not being able to tell Gene Roth from somewhat similar actor Merritt Stone [120], both of whom were in Earth Vs. the Spider (also 1959, and also an MST3k film; oddly enough, Stone doesn’t rate a picture on IMDB!), Roth actually recalls Gary Busey. Roth would also appear in a Hitchcock film: the 1966 Torn Curtain.

[29] [121] Mapes and his wife renew their love, but in a situation that will lead him to prison; Leland’s rich, wayward mother divorces her husband and returns to the States to “be a real mother” and arrives at the station in time to cross paths with her son’s coffin.

[30] [122] More ambiguous irony noted by TVTropes: “Porky Pig Pronunciation [123]: ‘Did I see you adulterat . . . adultering . . . oh, spiking that Coke [124]?’ — although if you listen closely you can hear the actress pronounce ‘adulterating’ correctly both times. It’s possible the character could be realizing the dolt she’s speaking to probably doesn’t know what the word means.” I think not, as she’s speaking to the writer [125], and although his novel just got its seventh rejection slip, he likely knows the word. The actress, as noted above, is the likely culprit.

[31] [126] See “’God, I’m with a heathen.’ The Rebirth of the Männerbund in Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables [127],” reprinted in The Homo & The Negro [128]; second, embiggened edition; ed. by Greg Johnson (San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2017); for a more recent look at the heist/Männerbund genre, see “Mid-Century Männerbund: Mad Men Mans-Up [129].”

[32] [130] TVTropes makes a good guess, while apparently working from the MST3k version: “What Happened to the Mouse? [131]: With his utility to the plot expended after the heist, Sidney completely vanishes from the film. But hey, someone had to drive the car home.”