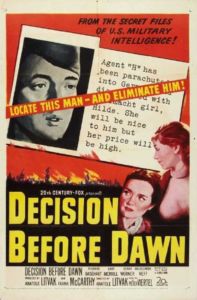

Decision Before Dawn: The Good German

Posted By Steven Clark On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledI first saw Decision Before Dawn on TV in the mid-sixties on Saturday Night at the Movies, seemingly banal filler that offered a surprisingly good row of early fifties movies such as The Big Carnival (previously reviewed by me [2]), The Desert Fox, and others that were gritty, blunt, and full of Cinéma vérité. This one always stuck with me, and I recently saw it again on YouTube.

What sticks? The realistic setting of this 1951 film in a battered Germany during the Second World War holding off the inevitable, and the strong performance of Oskar Werner as Corporal Mauer, a POW who is convinced by the Americans to go back into Germany on a mission that could supposedly end the war (don’t they all?).

Mauer is an easy touch. He has doubts about the war, and wants to be a Good German . . . to make up for the evil of the Third Reich.

Mauer and an officer surrender to Lt. Rennick, a moody Richard Basehart unsure about his reassignment to intelligence. Under Colonel Devlin (Gary Merrill), Rennick is shown a project Devlin is running involving German POWs who have been turned against the Reich to spy for the Americans. One of them, Tiger (Hans Christian Blech), is a prima donna spy. Devlin wants someone a little more humble, and Mauer is his man.

A companion who was with Mauer when they surrendered is a little too open about his dislike of Hitler and Germany’s blunders, and one night fellow POWs toss him out of a window. This changes Mauer’s mind, and he offers his services to Devlin.

I like the casting throughout this film. The German characters are all actual Germans or Austrians, and the Americans aren’t heroic. Basehart and Merrill don’t really seem like good guys; Rennick is uneasy and moody, and Devlin obviously sees the POWs as his pet project to please the brass. He seems to have good intentions, but is obviously willing to use people to get what he wants. I’m sure Devlin would have had a happy career in the CIA.

One of the American agents is Monique (Dominique Blanch), a French Algerian, and seems interested in Mauer, by this time called “Happy,” his code name. When Devlin asks her if she’s getting too emotionally involved with Mauer, she gets right to the point: He’s just a Boche. It reminds us that the theme of this film is people being used by others, and how emotions are a detriment in war and its element of distrust.

Of course, Monique probably had her own issues later. De Gaulle used the French Algerians to solidify his power, and later, in the Algerian uprising, easily sacrificed them to keep power in France and end the revolt of the native Algerians. This betrayal later led to assassination attempts, as depicted in fictional form in The Day of the Jackal.

Parachuted back into Germany, Mauer makes his way toward completing his mission by finding out the location of an armored corps. Again, I’m impressed by the cinematography; stark, brutal black-and-white filming amidst a background of wreckage, with people and soldiers jammed into trams and trucks, always being stopped to show their papers. The wartime damage shown is the real thing, as it was filmed in Wurzburg and Nuremburg, and I walked these palaces and streets, although they had already been repaired when I was stationed there.

The faces of the Germans are hard, unflinching, and fatalistic. No Hollywood casting here. There was, as I recall, such strength in those people.

Mauer isn’t a great spy. He always gives himself away, and on his first day, it’s known his parachute was found and the Gestapo are on the trail. His name is also on a German list of known captured, and so he will be suspect if he pops up in the middle of the Reich.

Mauer meets a woman on her way to a nursing post who knows him from his father, who is a doctor. He manages to stall her. He thinks to call his father to let him know he’s alive, then hangs up. Oskar Werner captures the genuine existential dilemma of his situation; he is an unperson, belonging no longer to his fatherland, but really not an American, either; Werner’s blank sadness contradicts his being “Happy.”

Mauer is befriended by Sergent Scholtz (Wilfred Seyferth), an SS motorcycle courier, but it’s a dangerous friendship. The man is too friendly, cynical, and always angling for drinks and free lodgings when none are available. His warmth, however, is shot away when Mauer says he was in France.

Where in France? Why, Alsace. Scholtz is angry. “That’s not French. It’s German. It always was, and we took it back.”

[3]

[3]You can buy Jef Costello’s The Importance of James Bond here [4]

Uh-oh. Mauer shrugs it off, but Scholtz has been tipped off.

As Scholtz drinks up, Mauer wins the attention of Hilde (Hildegard Knef). She’s a semi-hooker, and is intrigued by Mauer’s coldness. Werner plays hard-to-get very well, yet Hilde, for all her sauciness, is in pain. She admits to Mauer that she lost a child in a bombing raid. She opens her wound to him.

She’s aware that the Gestapo is after him, but it doesn’t matter. He must be a good man. He takes off, and she goes on.

Mauer’s on the lam, but for all his mistakes, he does get to the unit he’s assigned to tail. He winds up with Colonel Von Ecker (O. E. Hasse), commander of the brigade. He has heart problems, but is still a determined officer. Mauer witnesses a soldier brought before Von Ecker for desertion. The man pleads that he had to find his family, who had been bombed out. Von Ecker has no sympathy. Everyone has to do their duty.

Mauer, leaving the unit, passes the soldier, now dangling from a tree.

This would seem an example of Nazi cruelty, at least when I was a child, but again, Von Ecker is shown as decent, fair man. He is concerned about Mauer, since Mauer saves him from a heart attack. But the soldier executed was a deserter, and that’s what happens to deserters in war, and if you don’t hang them, there might not be an army. I remember how I was told the Nazis had executed hundreds of Germans for deserting, but the US had only executed one soldier, Eddie Slovik.

Not really true. We hung quite a few deserters, and desertion was a big, if hushed-up, problem. Need we remember the sainted Emmet Till’s father, who was hung for rape?

In Churchill’s War, David Irving recounts how many GIs in England deserted, became criminals, and were a nuisance to the British. Quite a few of them were black. Churchill was quietly annoyed, but he couldn’t afford to tick off FDR, who turned a blind eye to the misdoings of the colored troops that the British authorities hadn’t wanted sent to Britain in the first place. The British were told they had to take them on or else.

There is a quiet dignity and endurance that the Germans have that came out in this film. You see one woman with an artificial leg as a result of the bombing. Even the Gestapo agent pursuing Mauer isn’t some kind of Nazi robot. He’s flabby and near-sighted; you imagine all the best SS personnel had been siphoned off to Russia.

The film was considered very daring in showing Germans in an equal light, but early fifties movies had this kind of downbeat portrayal of life. See Paddy Chayefsky’s Marty, about normal, average-looking guys trying to find a girl who isn’t a “dog.”

Decision Before Dawn also recalls the film The Enemy Below (1959), where Robert Mitchum was a destroyer escort captain at war with a U-Boat whose captain (Kurt Jurgens) is shown as intelligent, humane, and every bit as human as Mitchum. This trend of humanizing the Germans was curtailed as the sixties came, but you still got to see the German side of things in films like The Battle of Britain or Cross of Iron.

It all died when the TV series Holocaust came out, and everything about the war ended up being about Jews, Jews, Jews. I noted a recent film about Dunkirk where the Germans were never even depicted — no faces, nothing. Just a strange enemy out there. This was in contrast to an earlier sixties film of the same event, where German commanders and flight crews were shown.

But back to Decision Before Dawn. I wondered, looking at the horrible damage inflicted on Germany, how Mauer could even complete his mission. He is a compassionate, uncertain, at times confused young man, and that type would have been easily susceptible to Allied propaganda. But Mauer can see what the Americans are doing to his country. He’s no friend of Hitler, and in the film few Germans are, but they keep fighting, because what choice have they? Nazi control is always apparent, but the wretched destruction and pounding of the cities by the bombers is certainly a statement on the merciless foe who is doing all of this for “democracy.”

The good Germans like Mauer could be understood as wanting a better life than the one Hitler gave them with a disastrous war, but he must have been aware of Allied propaganda, which called for Germany to be exterminated. The Morgenthau plan, which called for Germany to be pastoralized, as well as various pronouncements by Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt to the effect that the entire German officer class had to be killed off, as well as demands that most Germans be sterilized . . . The Allies never hid this, and Goebbels made sure the Germans knew it.

So really, why wouldn’t Mauer just be a good German in the POW camp and help the injured? Because he wants to do “something.”

Well, so did the German officers who tried to assassinate Hitler in 1944. They failed, and Hitler was disgusted. Why didn’t they just shoot him?, he argued. A bomb was cowardly. He was said to be almost relieved when it turned out to be officers, as he believed the working class would never have tried to kill him.

In Hitler’s War, David Irving reports Hitler’s summation:

. . . I keep asking myself what they were all after . . . As though Stalin or Churchill or Roosevelt would have been bothered for one instant by our sudden desire for peace! In eight days the Russians would have been in Berlin and it would have been all over for Germany — for good.

True. The Allies showed no interest in sponsoring any kind of coup against Hitler, and Churchill only hoped that when the Gestapo rounded up the conspirators, they would be killed. Fewer of them for the Allies to execute. There was little point in trying to make peace with the Allies. They — we — were bent on crushing Germany. Thus, Mauer is offering his life to the people wrecking his land and killing or maiming his people. The good German becomes a martyr for doing the right thing. It recalls the phrase “Win by losing” from O. T. Gunnarsson’s White Nationalist novel Hear the Cradle Song, which explains the Christian view of sacrifice. You die, suffer, and endure horrible torture, but it makes you superior to your tormenter. You win by losing.

In the post-war period, we were obsessed with finding “good Germans” who would help to build a democracy, fight Communism, and so on. This film was an example of the kind of German we wanted. Of course, it was all portrayed as if we and the Germans were equal allies, and that we would never coerce them . . . unlike the evil Russians.

The German Federal Republic that was established after the war broke all ties with Germany’s military past, and yet when they organized the Bundeswehr in the fifties as part of West Germany’s contribution to NATO (I remember reading a German publication at the time in which its officers proudly stated that they were not German officers, but “officers of NATO”). Germany has always been the most gung-ho NATO member, partly out of enthusiasm but also because they’re ordered to. But it’s tough to build a military while denouncing its traditions. We’re discovering that now by renaming military bases and ditching a lot of old heroes like Robert E. Lee for some obscure black PFC or social activist who did whatever in 1943.

In “democratic” Germany, the officers who plotted to kill Hitler are treated as heroes, but it still doesn’t work. They were, in effect, traitors, and if they had succeeded, it would have had no effect on saving Germany except to stop the killing, and even that wasn’t guaranteed had they not immediately surrendered unconditionally.

[5]

[5]You can buy Son of Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here [6]

I don’t say this to denounce them. I can see why they felt they had to do what they did, much like I understand Mauer wanting to do something good — but it’s better to stay with your own side. There usually isn’t any choice about it.

As for Mauer turning to the Allies after seeing his friend killed by fellow POWs, it was regrettable and perhaps savage, but that’s what prisoners do. If a GI had been pumping for Hitler while in a POW camp, he probably would have been killed by his fellows as well. In Stalag 17, another early fifties movie, director Billy Wilder’s film gives us a character placed by William Holden who is suspected by his fellow POWs of being a German sympathizer because of his cynical, unpatriotic attitude, and they savagely beat him for it. In Wilder’s film, no one comes out a hero. It’s a rotten situation. But Mauer’s good intentions might have been better served by not signing up with the enemy.

Mauer is a strong, decent man, and probably after the war he would have done a lot of good. As it is, he succeeds in his mission, but it all goes up in smoke. The great plan to end the war is negated by another Allied bombing raid that wounds a German general who could have surrendered his forces after being placed under heavy guard at an SS hospital.

There was no subtlety or tactical brilliance in Allied strategy. It was bomb and stamp the enemy into rubble and bones. Patton and Montgomery’s plans for sweeping tactical thrusts were rejected by Ike, who favored a grinding war of attrition. This traditional way of American warmaking began when Grant clawed his way to Richmond.

The film ends on a semi-sour note. Rennick escapes back to the Allied lines, and Devlin shrugs off the loss of “Happy.” He’ll keep up the program of using German POWs. It will become the standard American way of war: using someone else to do the slogging. The road from Devlin’s strategy leads through American strategy in Vietnam to the present day, where it’s acknowledged that we will fight Russia to the last Ukrainian.

Rennick is sadder but wiser, and content to be out of the shadow war and back in a conventional unit.

Decision Before Dawn was filled in a semi-documentary style, and the movie’s grittiness is one of it’s strengths — “telling the truth.”

Rennick understands Mauer is to be written off. He will only be referred to as “Happy” in American files. He is an unknown man. This is usually the fate of spies. Even in James Fenimore Cooper’s novel The Spy (1821), Harvey Birch, a simple peddler who is seen as a loyalist, is actually a spy for Washington, but his work must forever remain unknown despite his service. In his own way, Birch is forgotten.

Yet, Rennick came to admire Mauer. We see how the people he interacted with, from Hilde to Von Ecker, and even the Gestapo agent (for whom Mauer fetches his glasses so the agent can see before a gunfight), were affected by him. You watch this film and will never think of Germans as being faceless machines again. It would be interesting to see what Germans think of this film, especially since reunification, when the Jewish Holocaust propaganda really cranked up.

Rennick sums it up. “A man,” he says, “stays alive as long as he is remembered. He is killed only by forgetfulness.”

Yet, as Rennick is leaving, the driver asks about the mission. Rennick says little except that Happy was lost. The driver shrugs. “Oh, well. It was just another kraut.”

Change that word to “gook” or “raghead,” and you’ll have typical American gratitude to foreigners who support their war efforts. Rennick looks at the GI, saying nothing as he hops into the jeep and goes off to win the war.

It now seems that 75 years of being good Germans has led the country to shut itself down to save democracy in Ukraine, and there are some in the shadows who argue that America is partly doing this to destroy Germany as an economic competitor, although there are enough good Germans there to do the job without overt American backing.

It was poignant that, a few years after reunification, Germans began to talk about the war and their suffering, especially the bombing and starvation they had endured. There was open discussion about the bombings of Hamburg and Dresden, which killed hundreds of thousands of German civilians, and it had been more or less verboten to talk about the bombings before then. Reinhard Gehlen, a veteran of the Third Reich’s intelligence services, formed West Germany’s Federal Intelligence Service after the war. A spy ring jointly operated by Gehlen and the CIA was compromised in 1961 when agent “Felfe” was discovered to be an undercover East German agent who was sending lists of Western agents to the KGB and the Stasi. It was said that Felfe had taken the job mostly because of what had happened to Dresden. He hated the Americans and British for it.

I also noted that the Left clamped down on any German recollections of the bombing, as well as Allied atrocities against Germans, including the starvation of German POWs under Eisenhower. The German populace was, of course, expected to keep their mouths shut, be good Germans, and forget everything except suffering by the Jews. Or else.

I also think of how the stark, uneasy, and truthful depiction of an embattled Germany in Decision Before Dawn morphed into charming TV depictions like Hogan’s Heroes, where there is a Sergeant Schultz who “knows nothing.” I thought Scholtz in Decision Before Dawn was more likable and honest, but then Hogan’s Heroes was a show made by Jews and by and large featuring Jews in its cast. It was TV land, where Hogan and his gang pull off one espionage stunt per week. In Decision Before Dawn, even one espionage mission planned by Devlin was a long shot which ended up with losses.

Agents usually had a low survival rate. Interestingly, Americans posing as Germans were always caught by the Gestapo. They gave themselves away by various mannerisms, such as the fact that when they sat, they crossed their legs at a wide angle. Germans always cross their legs close. The agents who seemed to survive best were Jews, for obvious reasons.

As Marx said, when history is repeated, it usually becomes farce, and so it is that history eventually becomes a joke . . . at least in TV land. That’s why I enjoyed seeing Decision Before Dawn again. I thought of Rennick’s musing about being remembered, and about how the Germans have been drilled to forget — much like how we are now being similarly drilled to forget our history, race, and civilization. This film is a black-and-white world of truth and tragedy — cinema worth revisiting.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [7]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

- Fifth, Paywall members will have access to the Counter-Currents Telegram group.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[8]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[8]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.