The Challenger Disaster: Lessons for the Right

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 2,289 words

2,289 words

Anyone who remembers the 1980s can recall exactly what they were doing when the space shuttle Challenger exploded just 73 seconds after lifting off on January 28, 1986. People at the Florida launch site openly wept, pounded their fists on the hoods of their cars, and held each other. Schoolchildren looked at the televised images of the disaster with horror. The news media went into a frenzy, and President Reagan delivered a televised eulogy that evening that was probably his best speech ever [1].

There was also a series of naughty “Challenger Jokes” that circulated in the elementary school underground across America in the weeks following the tragedy. These jokes were cruel but terribly funny in a forbidden fruit sort of way — I definitely won’t repeat any of them here. These jokes were probably as much part of the grieving process as the memorial ceremonies, moments of silence, and tears.

The Challenger disaster was an emotional shock for the entire nation.

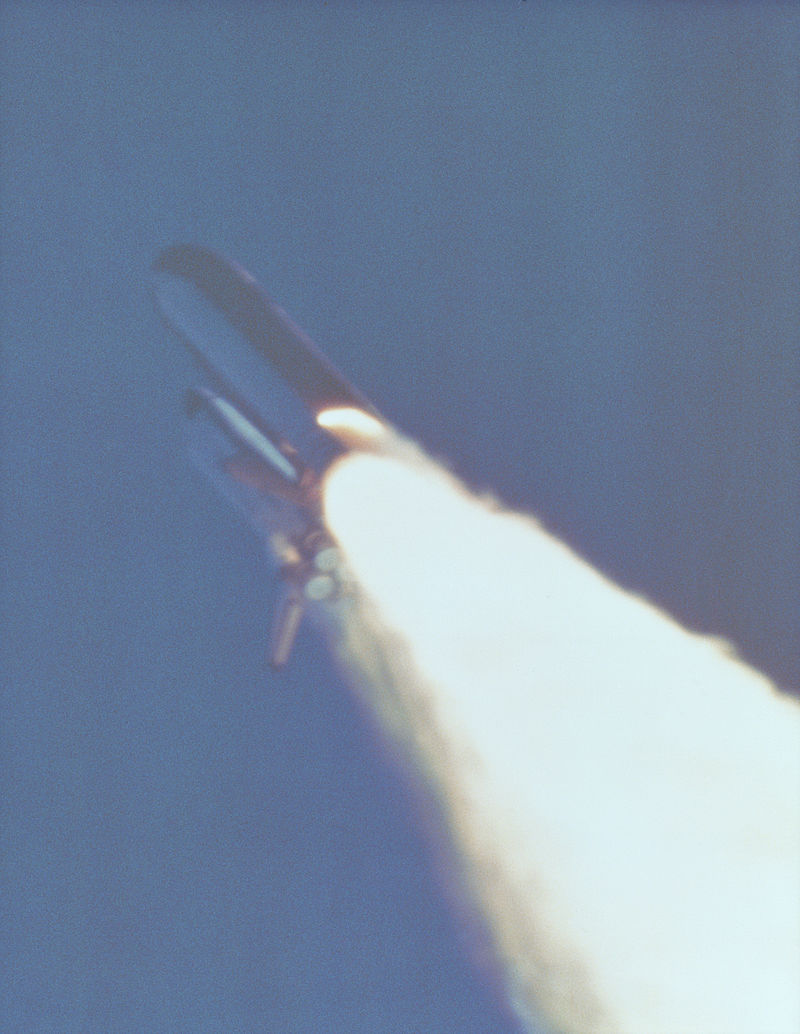

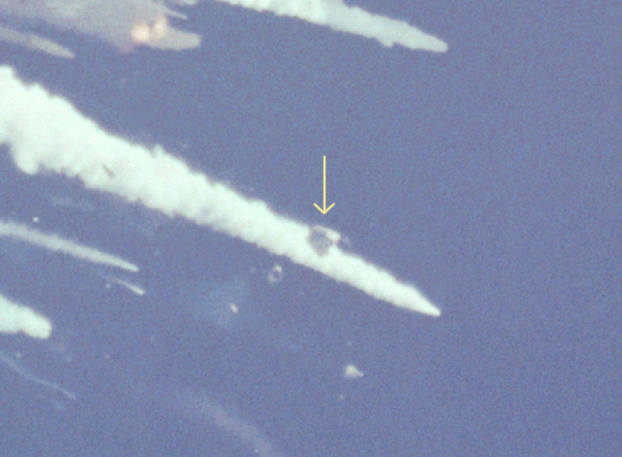

It later came to light that the rubber O-ring seals that kept hot gases from escaping the joints on the solid rocket boosters (SRBs) could fail in cold weather. This fact was well-documented and consistent over several launches. NASA decided to launch the Challenger even though it was covered in a shroud of ice that morning. Suffice to say, the O-rings failed immediately — burning away at the moment of lift-off. At 58.788 seconds [2] into the flight, a plume of fire leaked from the gap opened by the failed O-ring. At 64.66 seconds, that plume of fire had burned into the main fuel tank, and before anyone realized the seriousness of the crisis the shuttle was lost.

The plume of fire coming from the side of the SRB destroyed the Challenger.

There is a great deal to discuss about the space program in general and the Challenger disaster in particular. First, there is a racial angle to the space program. Next, NASA had considerable institutional cultural flaws that contributed to the tragedy. There is also the challenge of technical experts being meaningfully able to contribute to managerial decisions in a large hierarchal organization.

In 1986, one of the messages that the Challenger crew had to sell was “why we were in space.” In the decades since the Challenger crew slipped the surly bonds of Earth to touch the face of God, space has become a theater of war. It is only a matter of time before military operations in space will be timed to influence infantry operations on the ground. It is likewise only a matter of time before we have terrorism in orbit.

In other words, there’s no more “selling” space; you might not be interested in space — but space is interested in you.

Space & Race

The American space program really got going after the Soviet Union put Sputnik in orbit in 1957. In the following national panic, NASA was created.

NASA’s rocket designers and astronauts became national heroes, but racial politics were always a cloud over the program. Sub-Saharans in America hated the space program. They saw the money going to rockets and moon landers, and very badly wanted that bling. On the eve of the Apollo 11 launch, a junior varsity-level “civil rights” activist named Ralph Abernathy brought a mule-pulled wagon to the Kennedy Center to demonstrate that NASA dindu nuffin for the Africans. Abernathy didn’t realize it, but the protest demonstrated the different capabilities of the races in a stark way. The stunt was cultural appropriation, too. Africans didn’t develop the wheel and axle.

The criticism stung NASA, though. The 1964 Civil Rights Act is an illicit second Constitution [3], so the cry of the Congoid, however childish, had to be dealt with. NASA adjusted its astronaut recruiting program in the 1970s to include more blacks. The crew on the Challenger’s doomed flight was deliberately selected to be diverse.

Congress was also parsimonious in funding the space shuttle program partially to get more resources to dem programs. As a result, NASA needed to get paying customers to use the space shuttle, like the Department of Defense, to offset costs. The shuttle program was also expected to stay on a tight, profitable schedule. Meanwhile, manned spaceflight was a form of navigation less than a quarter-century old in 1986. Spaceflight was and is imperfectly understood.

Top: The makeup of the Challenger crew was deliberately made racially diverse. Bottom: The crew of the first shuttle launch after the Challenger disaster.

Organizations with a policy of “civil rights” will develop a culture where data is misread and trends are not noticed. The diversity push in NASA was certainly a factor in the enormous misreading of data in the lead up to the doomed launch.

Misreading Data

But the “civil rights” fog was only a small part of institutional cultural flaws in NASA that led to the tragedy. It is all well and good to understand that if your institution believes in “civil rights,” then data somewhere is being misread. But in the case of the Challenger disaster, there were more problems than just “civil rights” make-believe.

Sociologist Diane Vaughan studied the disaster in depth. She first ruled out the idea circulating at the time that the Reagan administration had pushed for the launch in spite of the dangers. She disagreed that NASA’s sensitivity to media criticism over earlier launch delays was an issue. She likewise ruled out the idea that NASA was making decisions based on the idea that expending lives was an acceptable cost of staying on schedule. She calls this concept an “amoral calculation.”

She argues that what led to the disaster is the “normalization of deviance.” Essentially, normalization of deviance is a flaw in an organization that occurs with the collusion of all — nobody realizes there is a problem. In the case of the space shuttle program, normalization of deviance started immediately.

The space shuttle’s components were developed from existing technology but the components had never been used together until after the first shuttle flight. Additionally, they were made by different companies, so all sorts of frictions and miscommunications were baked into the program from the beginning. While NASA tested the technology in-depth prior to the first launch, nobody really knew how things would work until after missions were flown. These damages (i.e. deviances), like scorched O-rings, became normalized since they were usually there and the shuttle always worked. Nobody really knew what right or wrong looked like.

The Challenger’s crew compartment remained intact after the rest of the vehicle disintegrated. It was not discovered until six weeks after the explosion. Three of the astronauts’ emergency oxygen packs were activated and it is possible the crew survived the blast and only perished when the compartment crashed into the Atlantic Ocean.

Vaughn argues that the working group culture that included the engineers that manufactured the SRBs and the management that made the decision to launch or not painted themselves in a corner. They had to launch. All their past decisions influenced their present reality. NASA had normalized deviance and their experience of past successes worked against them.

On a final note, to get NASA focused on the O-ring issue, three people on the Presidential Inquiry Board after the disaster needed to use unusual methods to bring out the truth. Dr. Sally Ride [1] [4], the first American woman in space, was given a chart that showed O-ring problems correlating with cold weather from some source — probably an engineer or lower-ranking action officer. She then gave the paper to USAF Major General Donald Kutyna. General Kutyna had developed a warm friendship with fellow board member and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman. After an evening together, Kutyna and Feynman hatched a plan to demonstrate that rubber O-rings would fail when cold. In other words, to get the truth out, two celebrities and a high ranking military officer had to get creative.

Hierarchy

Those more familiar with the O-ring issue were more certain that they’d fail than those in management. In other words, the sense of danger faded the higher one went up the chain. In the final meeting, held late at night, the question was raised if the cold weather was a problem. Most of the engineers at Thiokol, the company that manufactured the SRBs, wanted to delay the launch. But as the conference between Thiokol and NASA went on, Larry Mulloy, a manager at NASA, made a frustrated and sarcastic remark about “waiting until April.” Participants later said that Mulloy’s comments changed the meeting’s dynamic. Engineers now had to prove that the O-rings would fail. They couldn’t do that. The launch was a “Go.”

What happened on the eve of the Challenger launch should be further explained from a basic leadership perspective. If one is an engineer, a good place to work is on some sort of US government project somewhere so the dynamic at NASA can be repeated in a thousand other places and ways.

These projects are all organized in the same way. There are government officials — usually military officers or civil servants like Larry Mulloy at the top. They are both the client and the senior manager of the project. They are always highly experienced and usually veterans. Mulloy had been in the US Army. A little military service goes a long way. Guys that wore stripes in early adulthood have usually developed the skills to bend people to their will, and a sarcastic comment delivered at the right time can often do such a thing. An engineer, no matter how smart, must thus persuade a guy that represents the power of the US government. This can be quite daunting.

However, this doesn’t absolve a technical expert such as those on the engineering team at Thiokol from responsibility. The types of people that become engineers don’t always have the best human relationship skills. Crying wolf and constant arguing never get anyone anywhere. Insulting the boss also doesn’t work. Plus, continued insistence on problems with the product one has built — in this case, the SRB’s O-rings — is an implied admission that one has done a bad job.

Probably the only way that the O-ring issue could have been resolved without a spectacular failure in the eyes of the nation and world would have required an engineer with considerable technical know-how and personal charm to convince one of the senior NASA officials of the scale of the problem. That problem would need to be clearly defined and a solution had to be within grasp. The problem would need to be prioritized out of all the other problems in a complex system operating at the edge of human engineering. The manager would need to be so comfortable with his position that he could go before his management or a funding body like a Congressional committee and make the case for an expensive overhaul with the associated delays.

A good idea to sniff out normalization of deviance before an accident is to have some sort of meeting off-site, without the usual formality, to frankly discuss concerns. We haven’t seen the end of space accidents, but it is possible to have fewer of them with such a method.

Dealing with Failure

It is easy to lead when you are winning. What do you do when nothing is working? What do you do when your project has blown up in front of the eyes of your country and put millions of people in mourning? I’ve always wondered what to do in such a case. The Challenger disaster offers up an example.

As far as I can tell, NASA’s biggest problem was their slowness in getting information out. It allowed for accusations of a cover-up to develop. Furthermore, they didn’t have a good plan for a catastrophic failure. There was no protocol to follow. They winged it.

Some things did go right. The announcer on-site the day of the tragedy was frank about the situation. He kept his cool and didn’t curse, only stating that there was “obviously a major malfunction.” The director of operations at the Kennedy Space Center also spoke with a sense of professionalism and gravitas to the press. Vice President George H.W. Bush also chose his words wisely in the aftermath of the disaster.

I’d even add that Larry Mulloy, who became something of a fall guy for the disaster, behaved quite well when testifying at the presidential inquiry. He clearly stated how he saw the data and why he made the call he did. It is only in retrospect that it became clear he was wrong. He didn’t cry, behave poorly, use profanity, be sarcastic, be rude, or blame others. He kept his head up and laid out the facts as he saw them.

None, however, topped President Reagan’s speech. The Great Communicator praised the dead, comforted the living, and didn’t recount the horror in detail since everyone had seen the replay a hundred times. Reagan showed that the event had meaning. It was a masterful bit of rhetoric and anyone in a leadership role in any capacity should put themselves in Reagan’s shoes on that day before they must address their followers after a terrible event.

In the end, “The future doesn’t belong to the fainthearted; it belongs to the brave.”

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [5] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [6] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [7] It is a great tragedy for our people that Dr. Sally Ride (1951 – 2012) died without having children. It is imperative that we encourage smart and heroic women to become mothers.