The Hardhat Riot of 1970

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 2,535 words

2,535 words

David Paul Kuhn

The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution

New York: Oxford University Press, 2020

The Hardhat Riot of May 8, 1970 left a subtle and lasting impact on American culture. Sensitive liberals of the Useful Idiot type, like the horror author Stephen King, look upon the Hardhats with fear and loathing. The 1983 film, based on the book of the same name by King, The Dead Zone, shows the antagonist (played by Martin Sheen) wearing a hardhat.

The story of the Hardhat Riot is told in the 2020 book The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution by David Paul Kuhn. The Hardhat riot is part of the breakup of the Democratic Party more generally. Kuhn starts the story with the Democrat’s breakup in the 1968 Democratic Party Convention in Chicago, but the Party had been separating along its fault lines for at least two decades prior.

The Breakup of the Democratic Party (1945-1970)

Traditionally, the Democratic Party’s core supporters were white Southern Protestants and Irish Catholics from the cities in the northern US. From the time of Andrew Jackson, the Democratic Party’s ideology was to use the US federal government to help the Yeoman class of whites, i.e. blue-collar workers. As the Democrat William Jennings Bryant [1] put it [2]:

The man who is employed for wages is as much a businessman as his employer. The attorney in a country town is as much a businessman as the corporation counsel in a great metropolis. . . The miners who go 1,000 feet into the earth. . . and bring forth from their hiding places the precious metals to be poured in the channels of trade are as much businessmen as the few financial magnates who in a backroom corner the money of the world.

From 1932 to 1944, the only areas of the country that reliably voted Republican were stubborn Yankees in the granite hills of northern New England. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party was ascendant, powerful, and used to victory. But in 1948, [3]at the Party’s convention, Hubert H. Humphrey [4] started to talk about “civil rights.” The delegates from the Deep South staged a walkout. It was from the loose thread of “civil rights” and its associated African problems that started to unravel the party more generally.

There was also the nagging problem of Communists and their sympathizers within the Democratic Party. Due to that, Joe McCarthy of Wisconsin, who later became a Senator, switched parties and became a Republican just after the end of World War II. McCarthy’s defection is important. McCarthy had some Irish ancestry and was Roman Catholic — the Democratic Party’s policies and personalities were causing a defection of traditional supporters [1] [5] as early as the latter half of the 1940s.

Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 was also related to the breakup of the Democrats, as Kennedy was in Dallas to paper over the widening cracks caused by the Democratic Party’s embrace of “civil rights” as well as prepare for the upcoming 1964 election. His killer was a self-professed Marxist-Leninist who’d have been comfortable in FDR’s Party in 1943 but had no place in Kennedy’s Party twenty years later.

In 1968, the Democratic Party’s convention was a televised debacle. Richard Nixon eked out a victory in the general election.

The Rust Belt

In the 1950s and 1960s, New York City was a manufacturing town. Much of its population consisted of whites working blue-collar jobs. But then came the Interstate system and the suburbs. At the same time, New York City became the destination for Puerto Ricans and Negroes. The Puerto Ricans did cause some trouble, but the black migration was more widespread and devastating. Across America, the great cities of the North suffered the arrival of swarms of Sub-Saharans from the Deep South.

You can buy The World in Flames: The Shorter Writings of Francis Parker Yockey here. [6]

In 1965, New York elected John Lindsay (1921-2000) as mayor. Lindsay was a liberal Republican Northeastern WASP. He moved in the same circles as the Bush family and charmed the press in the same way as JFK. His mayoral candidacy is notable in that he created the high-low coalition of extremely wealthy and connected whites with poor, crime-ridden blacks.

As the 1960s continued on their unstable way, New York City became overwhelmed with job losses and crime — the latter scourge was fueled by blacks behaving in typical fashion. A large part of Mayor Lindsay’s base of supporters was black, though, and he was unable to bring himself to get tough on crime. Instead, then, like today, the high part of his coalition pushed a metapolitical narrative in the media that blamed crime on “society” and all but called anyone who complained about it a bigot.

Mayor Lindsay also was able to get favorable, though dishonest, media coverage. When news broke that the Christ-like Congoid, the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr., had been shot, Lindsay went to visit Harlem, where he was poorly received. The press downplayed the ugliness of his visit and glossed over the considerable black-caused disorder that followed in New York City. The story was spun to that of Lindsay the white savior.

Looming over all of this was the Vietnam War, which by 1969 was claiming 500-plus American lives per month.

Nixon’s War

When President Nixon took over the Presidency, his biggest crisis was the Vietnam War. Nixon was thus forced to deal with the strategic circumstances created by the two Democratic administrations preceding him.

Those two administrations which preceded Nixon’s had self-sabotaged themselves with “civil rights.” In addition to the problem of integrating a biologically different population with historical grievances against the white American mainstream, “civil rights” carries with it two other negatives. The first is that to truly believe in “civil rights,” one must misread data. The second is that if a white person buys into the philosophical presuppositions of “civil rights,” then one eventually arrives at a semi-religious interpretation of events where everything done in the past by whites is sinful.

The semi-religious anti-white “civil rights” narrative and frustration with the Vietnam War gave a great deal of energy to a Leftist social protest movement, often led by Jews. The first problem, that of misreading data, or more accurately, lying, caused ever-increasing problems in Vietnam.

To explain, the Johnson administration was less than forthcoming about major problems in Southeast Asia, such as the fact the North Vietnamese were moving supplies through the neutral countries of Laos and Cambodia. As a result, there was a situation where everyone knew about the Ho Chi Minh Trail, but for a time no American official could talk openly about it. (For further reading on this matter I suggest We Were Soldiers Once. . . and Young, by Joseph Galloway and Harold Moore.)

Something universally known but unable to be spoken of is also the premier social dilemma caused by “civil rights.”

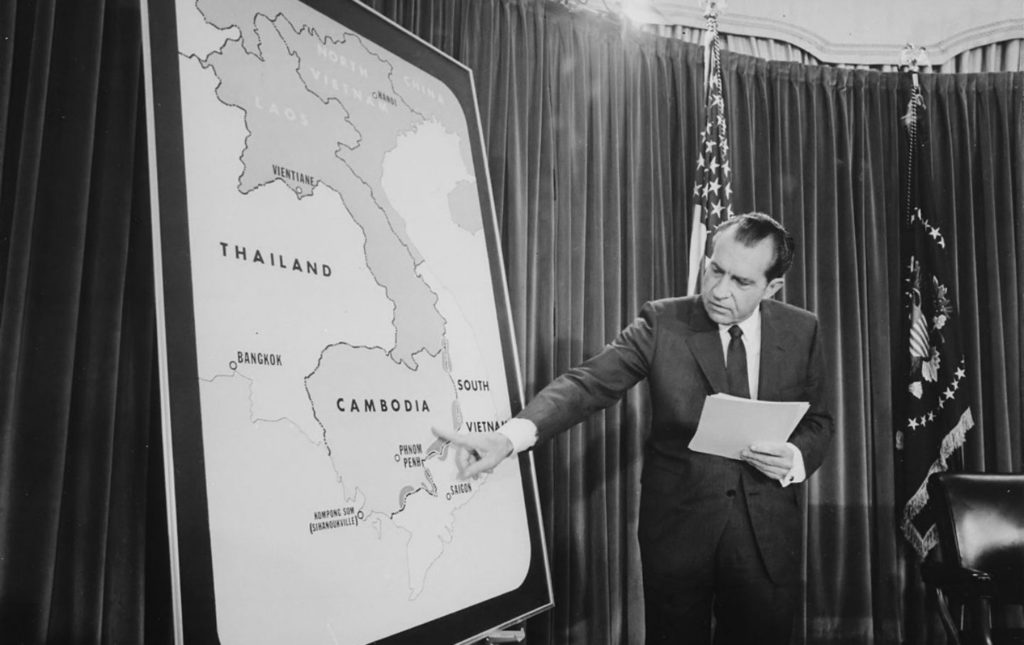

The frontier of Cambodia was in a situation where it was technically neutral but actually a major front in this conflict. Meanwhile, President Nixon had to enact his campaign promise to withdraw from the conflict and achieve what he called, “peace with honor.” To enact this plan, Nixon was required to use evasions, double talk, and betrayals, alongside bold action, bursts of honesty, and the diplomatic coup of exploiting the Sino-Soviet split. On top of that, he had to conduct military operations that violated the taboos of the earlier administration — like invade Cambodia and bomb Hanoi directly.

President Nixon announces the invasion of Cambodia. Many believed that Nixon “widened” the Vietnam War, but the North Vietnamese had been operating in Cambodia as early as 1963. Nonetheless, the invasion of Cambodia led to many anti-war protests.

Nixon had thus expanded the war after he’d been promising a conclusion. He also attacked a country many naïve liberals genuinely thought was neutral due to the lies of the earlier administration. Protests erupted across the United States. At Kent State, things got ugly fast. Protestors — many were outside agitators — burned down the ROTC building, and there were other rumors and threats, including putting LSD in the drinking water. When the fire department arrived to put out the blaze at the ROTC building, protestors fought them and cut the firehoses.

Ohio [7]

After the arson attack, Ohio governor Jim Rhodes (1909-2001) called in the Ohio National Guard to help restore order. On May 4, 1970, students held a rally. The rally quickly became violent, and soldiers from G Troop of the 2nd Battalion 107th Cavalry fired a volley into the protestors. Four students were killed.

The Ohio National Guard fires on protestors at Kent State on May 4, 1970.

There are all sorts of ideas regarding the use of force and freedom of speech that one can ponder upon at Kent State. [2] [8] I’ll only remark upon what I think are the most overlooked and important points.

- The moment that armed soldiers are deployed, the political leadership has acknowledged that there is a situation that might need to be met with lethal force. All law enforcement carries with it the threat of lethal force.

- Likewise, any soldier deployed with a weapon out of an armory or secure military installation — even within the bounds of the United States — must be given ammunition for that weapon if only to keep an armed bandit from stealing the weapons.

- There are no “shoot to maim” or “warning shots.” Any shots fired must be carefully aimed and are “shoot to kill.”

- The conflict between Yankees vs. Jews applies in the case of Kent State. The unit that carried out the shooting was from Ravenna, Ohio, a town founded by a Yankee from Massachusetts. The part of Ohio where Kent State is situated is also within an area reserved for settlement by the people of Connecticut [9]. I looked into the origins of one of the soldiers who likely fired and found that his family had lived in Ohio for several generations, and lived in the parts of Ohio settled by New Englanders as early as before the War of 1812. Furthermore, the National Guardsmen fired, in a volley, shots into the most violent part of the protestors; of the four students killed, three were Jews.

The Hardhats

In response to the shooting at Kent State, students protested across America and the white world, from Havana to Berlin. New York City’s Mayor Lindsay ordered flags flown at half-staff in memory of the fallen students. Students and anti-war activists (called hippies) staged protests in downtown Manhattan, near where thousands of construction workers, wearing hardhats, were building the World Trade Center.

The construction workers were mostly ethnic, Catholic whites who didn’t have a college education and were starting to feel the pinch of the deindustrializing economy as well as fear from the rising crime wave. Many were veterans. It was their kin and kind who were in Vietnam. They were outraged by the behavior of the anti-war protestors, many of whom were shouting obscenities.

On Friday, May 8, 1970, they’d had enough. They came down from their high steel workplace and started to beat up hippies. They were joined by hundreds of Wall Street office workers. Kuhn describes the riot in depth and has quotes from participants on both sides of the fighting as well as bystanders. The police were sympathetic to the Hardhats. Anti-war activists had long made a special point to insult police in the vilest ways, and when the Hardhats came, the cops were less than enthusiastic in stopping them.

The Hardhats flew the American flag and chanted “Love it or leave it.”

The Hardhats surrounded City Hall and demanded the flag be raised to the top of the staff. There was a tense standoff, and eventually, it was raised, which led to the mob singing patriotic American songs.

The Hardhats won the day, but it was ugly. The Hardhats used iron rods and the like as clubs and ganged up on anyone that looked like a hippie. Some later regretted their actions. Hardhats became embarrassed when one of their members inadvertently snatched a religious flag during one dust-up. The NYPD conducted an internal investigation and, for the most part, white-washed the conduct of their officers.

The Unstable Aftermath and the Working-Class White’s Long March to Less

The political effects of the riot were incredible. The Republican Party gained the votes of blue-collar white workers in a polarized political climate for the first time. Previously, that only happened when the GOP fielded an overwhelmingly popular candidate, such as Dwight Eisenhower. Over the next month, hardhats staged rallies, and the coalition that elected Reagan consisting of Evangelical Protestants, working-class whites, and anti-Communists was formed.

Mayor Lindsay moved further to the political Left. He became a Democrat and his coalition deeply influenced George McGovern’s run. The coalition that Lindsay created — wealthy whites, poor and troubled non-whites, Leftists, and deviants — is mostly a losing one. In 1972, this coalition lost badly. However, Barack Obama did ride that coalition to victory in 2008.

This high-low coalition remains dangerous. Its adherents remain believers. They are unable to visualize African crime or draw any conclusions about it. They arrange all Sub-Saharan uplift schemes so that blue-caller whites pay the price for that scheme. Their position in the economy is so secure that no adjustment in trade affects them. They are comforted, not challenged, by the press. They are bedazzled by loud, radical protestors and they’re never able to follow, Edmund Burke style, the logic of Leftism to its bloody endpoint.

Kuhn quotes James Farmer, a “civil rights leader” and black official in the Nixon administration, who remarked that “when the hardhats beat on kids, they think they are beating on blacks. And the blacks know this too” (p. 271).

I believe Farmer was correct. Many of the anti-war protestors of the New Left supported “civil rights” and black criminality. Additionally, the social narrative was such that no white could criticize African pathology or even accurately describe it. Republicans, swelled by blue-collar whites, thus focused on “bussing” and other proxies rather than black crime and the trouble of the illicit second constitution [10] that is the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

The Republicans haven’t done much to support blue-collar whites since the 1980s, although recently President Trump has enacted trade policies that might help them. Instead, the blue-collar whites experienced a terrible economic decline, and most recently they have fallen victim to the opioid epidemic [11]. It has proven to be extremely difficult to manage the economy in such a way that ordinary blue-collar whites can thrive economically.

In other words, the work of the Hardhats is unfinished.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [12] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [13] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [14] There is probably some sort of Blood Quantum to this defection. Joe McCarthy was not even mostly Irish. One can speculate that German Catholics in the North defected faster than Irish Catholics.

[2] [15] Indeed, the situation was not unlike that surrounding the Boston Massacre. John Adams, who later became the second US President, successfully and eloquently defended [16] the British soldiers.