Blaming Your Parents

Posted By Greg Johnson On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,444 words

Audio version here [2]

In the past, people used to blame the gods or the fates for their misfortunes. These days, they like to blame their parents.

- “My parents were sedentary and fat, and their bad example is why I grew up sedentary and fat.”

- “My father was always uptight. And now I’m uptight and can’t enjoy life.”

- “Growing up with a mother who drank, it was natural that I would take to drink as well.”

- “My father never praised me for anything, which is why I lack self-esteem.”

- “My parents gave me up for adoption, which is why I have trouble forming close bonds with people today.”

And so forth.

All of these arguments assume that the parents did something wrong. They all assume the premise: “If my parents had done something different, I would not have these problems.” The underlying assumption of this premise is nurturism, the idea that our upbringing is what accounts for most of our psychological traits.

Nurturism, of course, is intuitively plausible. Obviously the things we are exposed to in life will have some effect on us. Otherwise why would we have senses in the first place? But it turns out that a lot of our basic personality traits, including the things that we are inclined to blame our parents for, are hereditary.

Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (2002) is a powerful critique of the nurturist assumption in the human sciences. But to my mind, the most persuasive evidence for fine-grained hereditary determination of tastes and personality traits are studies of identical twins, especially identical twins raised apart often in very different home environments. The best summary of these studies is Nancy Segal’s Born Together―Reared Apart: The Landmark Minnesota Twin Study (2012). I also recommend her captivating popular books, Entwined Lives: Twins and What They Tell Us About Human Behavior (2013) and Indivisible by Two: Lives of Extraordinary Twins (2007). These studies show that twins raised apart in different environments have a lot more in common with one another than with their adoptive brothers and sisters raised in the same environment. Also, as one grows older, the effects of nurture become weaker as nature asserts itself.

Now, for my purposes here, one does not need to believe that all our tastes and personality traits are hereditary. One simply needs to accept the possibility that the traits you blame your parents for are hereditary. Just try the idea on for size:

- Maybe the reason you and your parents are sedentary and fat is because you all have genes for those traits.

- Maybe the reason you and your father are uptight and can’t enjoy life is because you both have genes for those traits.

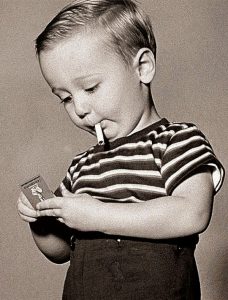

- Maybe you and your mother are drinkers because you both have genes for alcoholism.

- Maybe your father did not praise you because he saw too much of himself in you. In other words, you both had low self-esteem, and maybe it is genetic.

- Maybe the reason your parents gave you up for adoption is they had trouble forming an attachment to you, which means that your difficulty forming attachments might be genetic.

Maybe you’d be pretty much the same even if your parents had given you up for adoption — or, in the last case, had not given you up for adoption.

Which means that your parents did nothing wrong. They just created you the only way they could, with the genetic material they had on hand, which was passed on from their parents. They didn’t get to choose some traits and exclude others. That wasn’t possible. Your genetic makeup is a package deal. And unfortunately, it wasn’t a perfect package. Newsflash: nobody’s perfect.

Maybe in a world where genetic engineering is an affordable option we can start blaming our parents for not making us perfect, but that is not the world we live in.

Of course, you might blame your parents for creating you in the first place. But it is incoherent to believe that your very existence is a crime committed against you by your parents. After all, you do have the option of suicide. And every day you forego that option, you are taking on a greater and greater share of the “blame” for your continued existence. At a certain point, you have only yourself to blame.

I know that there are legal abominations called “wrongful life” suits, but they make absolutely no sense. The legal system should not be a mechanism for giving vent to unhinged spite. (There goes divorce court.) Wrongful life suits set a dangerous precedent, for they make no sense unless we regard abortion as a moral obligation in certain cases. Even if you believe abortion is a right, a right is something you can choose not to exercise as well. An obligation is something you must do. We simply cannot risk making abortion obligatory in a world ruled by white-hating and man-hating Leftists.

But why entertain the idea that your misfortunes might arise from nature rather than nurture?

Because it makes our misfortunes easier to bear.

If an apple falls from a tree and hits you on the head, there’s no question that it hurts. But how would you feel if you discovered that the apple had been thrown at you? Or dropped by a negligent apple-picker? Obviously, it would add insult to injury. The physical pain would be the same, but on top of the pain, you would also feel indignation. Because you have not just been hurt, you have been wronged.

The pain in one’s head can fade quickly. Not so with the indignation. To satisfy one’s indignation, someone needs to be punished. And when one cannot get satisfaction, one’s indignation turns into bitterness, which poisons one’s soul and wrecks one’s relationships. Bitterness is a kind of neurosis. Neurotics have unresolved issues from the past. When they encounter people who merely remind them of those unresolved issues, or the people they blame for them, their anger is triggered, and suddenly an innocent person is subjected to bewilderingly inappropriate behavior.

If one comes to regard one’s misfortunes merely as misfortunes, rather than something inflicted upon us by malice or negligence, one’s underlying problems will remain. But one’s attitudes and feelings about them will change. One’s indignation and bitterness will slowly dissipate if one keeps reminding oneself that human malice or negligence were not at work.

Once you see your genetic heritage as a package deal, you can reflect on the good qualities that are entwined with the bad ones, which takes the sting out of accepting one’s fate and might even pave the way to loving it.

Maybe once you stop thinking your genetic misfortunes are injustices, for which you must receive satisfaction from someone else, you will start thinking they are simply problems that you yourself can overcome. Just because you have genes to be sedentary and fat does not mean you have to give into them. Just because you have trouble forming connections does not mean you are condemned to loneliness. Just because you have genes for alcoholism does not mean you can’t be sober. And so forth. It might be hard, but who said life would be easy?

One’s relationships might improve as well. Instead of feeling anger at one’s parents, one might even begin to feel compassion for them, for they are victims too. One will also be less likely to burden friends and strangers with embittered outbursts.

The whole world will look different once you no longer see it through eyes jaundiced by resentment.

If blaming our parents falls out of fashion, should people go back to blaming gods for our misfortunes? No. That would be no improvement. Religion is just another version of the idea that there are minds and wills behind our misfortunes, although in this case they are disembodied, inscrutable, and capricious. If we blame the gods for our misfortune, that simply means that religion magnifies our suffering by doubling it with indignation and bitterness. This is one way to understand why the Epicureans regarded atheism as therapeutic.

The underlying assumption of this argument is that even though genetic determinism is an immensely powerful force, our beliefs about what is determined by our genes also have the power to alter our feelings and the course of our lives. This makes sense, for we would be ill-suited for survival if the only information we could use were hardwired into our genes. The evidence of our senses and the power of our reason are also tools for securing survival and pursuing happiness. If these words can change your beliefs, they can change your life for the better.