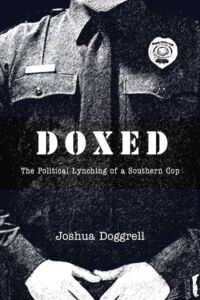

Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop

Posted By Anne Wilson Smith On In North American New Right | 1 CommentJoshua Doggrell

Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop [2]

Columbia, S. C.: Shotwell Publishing, 2024

“Pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it.” Cut off the support network and isolate the target from sympathy. Go after people and not institutions; people hurt faster than institutions. — Saul Alinsky, Rules for Radicals

The modern phenomenon of “doxing,” or publicizing personal information about private citizens, is one of the most dastardly and yet effective tactics of the modern Communist movement. In the Internet age, there is an unprecedented ability for activists to easily dig up private or little-known information about their political opponents, repackage it into digestible propaganda, and quickly broadcast it to millions of people, thereby whipping up an angry mob demanding punishment of the thought criminal.

We see this happen nearly every day, but we do not normally experience it from the perspective of the target. A new book, Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop, offers readers a window into this experience. The book is authored by Joshua Doggrell, an Alabama police officer who was ousted from his career in 2015 in the wake of a Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) smear campaign highlighting his membership in the League of the South.

Doggrell had served for 18 years as a law enforcement officer in Alabama and had worked for the City of Anniston for nine years at the time the SPLC published their hit piece on him. The SPLC Hatewatch blog “uncovered” Doggrell’s membership in the League and created an inflammatory video where they presented an audio recording of him delivering a speech juxtaposed with footage from an early 1960s racial incident where police brutality was alleged. Even though the incident took place before he was even born, and his League membership was already common knowledge within his police department, the propaganda still had its intended impact.

Doggrell’s record of service was outstanding. He had received multiple commendations, a series of promotions, and no complaints of any kind from either the public or fellow officers. Not only was his record impeccable, his membership in the Christian, secessionist organization League of the South had been disclosed to the Anniston Police Department prior to his hiring. This was therefore well known in the Department and had never before been considered problematic.

[3]

[3]You can buy Greg Johnson’s It’s Okay to Be White here. [4]

After a single citizen inquiry in 2009, the Department had formally investigated Doggrell’s League membership and concluded that his activities were a legitimate exercise of his Constitutional rights and were not in conflict with his duties as a peace officer. It would therefore seem that if anyone was in a position to survive an attempted “hit” by the radicals at the SPLC, it would be Doggrell. This makes the fact that the city quickly cowed to the character assault by firing him all the more disconcerting.

Readers of the book experience the fallout from the doxing through Doggrell’s eyes, sharing his sense of abandonment by fair-weather friends and betrayal by officials who valued public perception over justice and duty. We feel his immense frustration upon discovering that, when besieged by a public-relations firestorm, one’s long-standing good reputation and the objective truth are utterly irrelevant. Doggrell writes that the city “fired me on 17 June 2015 in order to attempt to satisfy the hounds of political correctness, then spent the next several months scavenging for reasons to validate it.” Copious evidence is provided that the local officials who might have stood for truth and fairness failed to do so.

One regret expressed by Doggrell which may be instructive to future dox victims is his decision, based on his attorney’s advice, to remain publicly silent while awaiting his court date for a lawsuit brought against the City: “I now consider that a major mistake on my part, because it allowed the city to set the narrative in the media and convince the public that their decision was justified, and I was some kind of monster.”

His day in court did not provide any satisfaction, either. Though ample evidence of his professionalism and fairness were presented, it could not overcome the insinuations of racism. The trial included belabored analysis of old social media posts — some of which had nothing to do with race, and some posted by other people that Doggrell had not even seen before! A large portion of the trial was spent questioning League of the South President Dr. Michael Hill, since some of Hill’s public statements had been used to characterize Doggrell as an extremist. While on the stand, Hill diplomatically explained that his personal posts were not necessarily indicative of the League of the South’s official positions, and that while he liked and respected Doggrell, the two men disagreed about many things. The use of this guilt-by-association tactic underscores another important point with regards to the dox issue. Doggrell asks, “If this line of scrutiny can be used . . . I ask you: Who among us is safe?”

Doggrell recounts his struggle to support his family in the days after his firing. Initially, donations from empathetic strangers helped get his family through the lean times. He eventually found work, and despite the fact that it was low-paying and unsatisfying, the devout Christian was grateful to God for this provision. Doggrell also drew encouragement from his roots, reading history books about the trials of Confederate soldiers.

With optimism and determination drawn from his faith, Doggrell slowly but steadily put his life back together. In this way, Doxed not only documents the personal experience of living through “cancellation,” but provides instruction and hope.