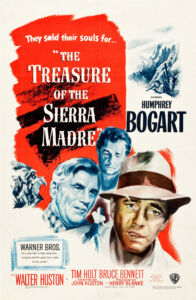

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | 18 CommentsJohn Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), starring Humphrey Bogart and Walter Huston, is a classic drama about three white prospectors searching for gold in the wilds of Mexico. Since the movie is older than most of my readers, I feel free to summarize key plot elements, but I will leave plenty of surprises.

The movie begins in Tampico, Mexico in 1925. Treasure was one of the first Hollywood films to be shot on location outside the United States and makes excellent use of local color. Humphrey Bogart plays Fred Dobbs, an American migrant laborer in Mexico. Yes, there was a time when Americans went to Mexico looking for work. Dobbs, however, is between jobs and down on his “luck,” although it quickly becomes apparent that he makes his own luck, spending scarce money on lottery tickets, alcohol, and a visit to a barber.

Eventually Dobbs teams up with another down-and-out American, Bob Curtain, played by Tim Holt. In a flophouse, Dobbs and Curtain meet another white American, Howard, an old prospector played by Walter Huston, the director’s father. Howard convinces them that there is gold to be found in the wilds, so when Dobbs and Curtain raise some capital, they team up with Howard and become prospectors.

Act Two of the film is the search for gold. It is a well-told adventure tale. In Act Three, they find gold and begin mining it. At this point, the drama takes a psychological turn. Howard is a rational man. He lays out all the risks, including the risk of betrayal by one’s partners, and takes the necessary precautions. Of course they need one another to mine the gold and protect one another from bandits and wild animals. But Dobbs, who has been disagreeable from the start, begins to get paranoid about his partners.

When a fourth white American, Cody (Bruce Bennett), shows up at the camp and asks to join them for a quarter share of what he helps dig out, the three are faced with a problem. If they take him on, their shares of the remaining gold are reduced. If they send him away, he could turn them in to the authorities or bandits.

It makes sense to bring Cody on board. A reduced share doesn’t really matter, for two reasons. First, they have no illusions about being able to dig up all the gold, and time is their enemy, for with each passing day, the chance of being discovered by bandits or Mexican troops rises. Second, a fourth pair of hands would make them more productive, allowing them to meet their goals and get home quicker. In short, Cody would pay for himself. Beyond that, a fourth gun would also come in handy if bandits show up.

Dobbs, however, is not just paranoid, he’s also extremely greedy and slightly stupid. Earlier, the prospectors have decided to quit when they have a certain amount of gold, for if they keep digging forever they risk discovery and would never be able to enjoy their wealth, anyway. But once they find gold, Dobbs wants more and more. Dobbs is also more fixated on preserving or increasing his nominal share of the gold than in increasing the actual amount they dig up. Thus he wants to kill Cody to protect their secret and maintain his share.

Dobbs almost succeeds in killing Cody, but he is saved when the camp is attacked by bandits, underscoring the need for white solidarity. It is a memorable scene. The bandits are utterly grotesque and palpably untrustworthy. This is the source of the “We don’t need no stinkin’ badges” meme. Today it would be condemned as “racist,” even though Huston’s portrayal of Mexicans is fair-minded overall.

The bandits are routed, but Cody is killed. Curtain and Walter are sorry to lose him. He might well have saved their lives. But Dobbs is happy to be rid of him.

[2]

[2]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here [3].

The final act sees the return of the three prospectors to civilization with their treasure. When Howard is forced to stay for a while in an Indian village, Dobbs refuses to wait with him, so he and Curtain continue to haul their goods out of the wilderness, even though two men are more vulnerable than three.

At this point, Dobbs is completely mad. He refuses to sleep because he is afraid Curtain will kill him and steal his gold. Naturally, Curtain can’t afford to sleep, either, for fear that Dobbs will kill him. Curtain could just kill Dobbs, but it would be almost as unsafe to be alone as with Dobbs. So he prays that Howard will return soon. The suspense is unbearable.

When Curtain nods off, Dobbs shoots him and leaves him for dead. While Dobbs is drinking greedily from a watering hole, three of the bandits they fought earlier sneak up behind him. It sure would have been handy to have Curtain and Howard there, to watch his back and even up the odds, but Dobbs chose otherwise. He soon gets what he deserves. The bandits cut off Dobbs’ head and steal his train of burros. They are only interested in the burros, though, so they discard the bags of sand that are weighing them down . . . That’s the Third World for you. Treasure does, however, contrive happy endings for Curtain and Howard.

Treasure was modestly successful on first release, making back its budget and a bit more. But it soon became clear to the industry and the public that the movie itself is a treasure. Since then, Treasure has been included on many directors’ and critics’ “best” lists. Sam Raimi ranked it as his very favorite film. Stanley Kubrick named it his fourth all-time favorite.

Before your very eyes, Fred Dobbs transforms into one of the most loathsome villains in cinema history: petty, irrational, murderous, and ultimately self-destructive. Dobbs is probably Humphrey Bogart’s greatest role. Vince Gilligan of Breaking Bad claims that Fred Dobbs was an inspiration for Walter White, which strikes me as terribly unfair to White. Paul Thomas Anderson also cites Dobbs as an influence on the character of Daniel Plainview in his There Will Be Blood.

Shockingly, Bogart’s performance was not nominated for an Oscar or any other awards. Walter Huston, however, won Best Supporting Actor for Howard, truly one of his finest roles.

John Huston also won Oscars for Best Director and Best Screenplay. Huston directed 37 feature films, writing the screenplays for many of them, including such classics as The Maltese Falcon (1941), Key Largo (1948), The Asphalt Jungle (1950), The African Queen (1951), and The Man Who Would Be King (1975). I am also fond of his little-known adaptation of Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood [4](1979).

Huston had a somewhat “naïve” approach to filmmaking. He always focused on the story. He regarded cinematic technique as something you look through, not at. Nevertheless, there are moments in Treasure where I found myself in awe of Huston’s direction, such as the sweeping opening shots of Tampico, or a bar fight that discards all cinematic clichés and seems astonishingly real.

I highly recommend The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. The script, direction, and performances are first-rate. Treasure is highly entertaining as an adventure. But what makes it a classic are its explorations of character and complex dramatic conflicts. There is no shred of anti-white propaganda, and beyond that, it has an important message about white solidarity. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is very much a Hollywood film, but it is Hollywood at its best.