The Dark Side: Paul Kersey’s Whitey on the Moon

Posted By Mark Gullick On In North American New Right | 18 Comments [1]

[1]You can buy Paul Kersey’s Whitey on the Moon here [2].

2,514 words

Black people do not like to think about history too much, because Black people don’t exactly have an excitingly stellar history . . . — Paul Kersey, Stuff Black People Don’t Like: 365 Days in Black-Run America

We once went to the Moon. We can’t go back now… — Paul Kersey, Whitey on the Moon

If history is written by the victors, we should assume that maxim applies to the current culture wars just as much as hotter exchanges. What we are witnessing, like onlookers at a 1960s moonshot, is a history which may be replaced one day, maybe very soon — expunged, overwritten, wiped clean like the blackboards schoolchildren used to be allowed to use. It is happening overtly in the United Kingdom, slavishly following as it always does the lead of what Paul Kersey calls “Black-Run America” (BRA). For both the United States and the United Kingdom, race will decide our future, so we had better grab our racial history while we can, and learn from it.

Paul Kersey is one of race realism’s most insistent and consistent voices. My Kindle collection has its very own “Black” section, a small wing of its ever-expanding library, and of the lucky 13 books on that wing, five are by Kersey. Well, six now. Kersey has been charting the entropic nature of American blackness for many years, and monitoring the resultant drop in quality of life for the white donors supplying the tax money for this failed — built to fail — project. It may be an odd metaphor to choose, but willfully-maintained black dysfunction is bleeding America white. And it is also costing white America its ability to progress in other areas.

Exposing the grim economic reality of BRA and highlighting the social carnage caused by what he terms the “black undertow,” Kersey is an archivist of dysfunction. His almanacs of violent black crime, fraud, mismanagement, theft, and anti-social ideology chart the fall of various famous American cities and, as the statistics and the details and the rap sheets march relentlessly on, a picture emerges of just how misguidedly blind America’s attitude toward race really is. In this collection, Whitey on the Moon (WOTM), the author shifts focus from the urban squalor that is his stock in trade and turns his attention to the space race. It may seem a giant leap — to coin a phrase — from the decline of Detroit and Baltimore to the Apollo space missions and NASA, but Kersey shows the link. Interlocking policy decisions intended both to increase the number of blacks involved in the space program, and to scupper that same world-historical achievement, showing that no matter how large and integral the organization, the worm of diversity can always crawl in (or be introduced). Any of the West’s uncountable organizations, private or public, that have installed diversity departments into their apparatuses since NASA led the way has acted out of fear — not fear of a black planet, something really worth fretting about, but a systemic fear of censure.

Kersey plots the route from the time when NASA executives went from saying, “Well, we pocketed the Moon, when do we put a guy on Mars?” to “How the hell do we get Dwayne — or preferably Eliza — a better job than janitor?” Kersey joins some impressive dots, not least of which is the formula that says that if John F. Kennedy had not been assassinated, a black man named Ed Dwight might have been the first black man in space, even the first man on the Moon, racial capability and white backup permitting. The administrative arm of Kennedy’s Camelot pressured NASA to get a black man into the astronaut training program, and effectively worry about the Moon another time. The pressure to recruit racially was immense, and reminds us once more that affirmative action is no recent phenomenon. Kersey also keeps in sight the axiom that affirmative action equals non-meritocratic recruitment.

Dwight was in fact a pilot, although hardly a high-flier in the metaphorical sense. Of 26 applicants for the program, the top 11 were admitted to the astronaut training program. Dwight came 26th and was rejected, right up until NASA changed the rules under pressure from the White House. Why not expand the successful applicant list to 15, and make Dwight the 15th? Just saying. This was duly finagled, and Dwight was in. And, when his lack of ability and acuity finally forced his rejection, we have a reminder of a cast-iron law of deep-state affirmative action: White men who stand in the way will be harried for doing their jobs.

[3]

[3]You can buy Mark Gullick’s novel Cherub Valley here [4].

The fall guy for Ed Dwight was a man called Chuck Yeager. He doubled down on his decision to can Dwight, adding that in the trainee body the only resentment apparent was that of Dwight’s fellows, not because of his skin color but rather the fact that he was on the course at all. When meritocracy is dismantled for political gain, not everyone takes kindly to it.

The Dwight incident was all about Kennedy’s personal standing with blacks, who were then (as now) important fashion accessories for the political class. Kennedy wanted “the esteem of black people,” Kersey writes, and JFK was prepared to use NASA to get it.

A central theme of the book is the resentment of blacks over the cost of the Apollo missions. But, as Kersey repeatedly shows in his other books, it is scarcely a credible criticism of the Apollo program that the money could have been better spent elsewhere. That would be an amount on top of that which has already been spent — and wasted — on that same ethnic “elsewhere.” When you read the seemingly endless list of grants, subsidies, finance initiatives, loans, and all the other cash gifts designed to persuade blacks not to improve their own situation, the Moon landings look like money very well spent, if only by virtue of not being misspent by failing to achieve its goal. There are also the space program’s technological offshoots, something else from which blacks benefit despite having had no input.

Was the cost of Apollo’s space program justified? Could the US have spent this vast tranche of tax money on improving life for black people at ground level instead? Well, yes, they could have done that, and Paul Kersey tells us with spaceflight precision what happened when they did do just that. Detroit is never far from Kersey’s analysis, and he often tags that blighted city as the future of America, calling it “the world’s greatest experiment, proving racial differences in intelligence and behavior exist.”

An awful lot of blacks were mighty unhappy that, to quote the Gill Scott-Heron song that gives the book its title, “Whitey’s on the Moon.” One figure who pops up regularly like a puppet devil is the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, “the man who succeeded [Martin Luther King] as the chief agitator.” The Reverend led a mule train to Cape Canaveral to protest an Apollo moonshot, intending to make a statement of humility and the woes of blacks at the hands of whites. Instead he showed the world how failed the black enterprise is and always has been. Abernathy’s raggle-taggle band of resentful miscreants were “the only major Black participation in the launching.”

But while blacks may not have liked whitey being on the Moon, whitey sure liked the idea of blacks being up there, however many of business and technology’s fundamental principles had to be rerouted to do it. One of the great and influential race agitators was a woman named Ruth Bates Harris in the 1970s, a grifter whose reports show the self-defeating (for whites) nature of diversity hiring. This snippet from one such is a perfect miniature of the programmatic dysfunction imported to an otherwise efficient concern by the imposition of racial quotas: “NASA has failed to progress because it has never made equal opportunity a priority.” NASA put men on the Moon. That is a curious definition of “failure to progress.”

There are moments of what we can only call dark humor in the book, even if it is whistling past the graveyard. Ugandan President Yoweveri Museveni bemoaned the fact that Africa was the continent without a runner in the space race: “The Americans have gone to the Moon. And the Russians. The Chinese and Indians will go there soon. Africans are the only ones who are stuck here.”

I laughed out loud on reading this. Yes, O great chief. And we are stuck here with you, which might be why we are — were — checking out other planets. Anywhere that ain’t downtown, y’know? And it looks like we’re stuck here with you for the time being. After a string of successful missions, Apollo 18 and 19 were cancelled, and Kersey has no hesitation in plotting the course of the diverted funding. The choice was clear: “The stars or Detroit.”

Blacks can help out here on Earth, however, when it comes to space travel. In the movie Independence Day, Kersey wryly notes, an invading craft is downed, along with all its hyper-technology and genius crew, by some African bushmen with spears.

The dating of each piece in WOTM gives a diaristic feel, and the shocking thing is that the book is composed of pieces from ten or so years ago. This is what always looks so portentous when you read books about the West’s collapse and the reasons for it, and you realize they are a decade or more old. Things are unlikely to have improved in the interim.

The book’s serialistic structure is consistent with Kersey’s other work, which has the reiterative, rhythmic feel of samizdat, and this leads to the repetition of central points. But there is nothing amiss with that in and of itself. You’ll find repetition of a central theme in Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and Melville’s Moby Dick, transcendence in the former and a whale in the latter. If you are going to make an important point, stating it once and once only diminishes its importance. In Kersey’s work, the central supporting wall is, I would suggest, the ineradicable fact that whites pay for black dysfunction twice: once at point of sale, financially, and twice with the ongoing dysfunction that money allows to continue. This book simply relocates the locus of that financial chaos from the inner cities that are Kersey’s usual haunt to the space race.

Other ways of rerouting money which could have been used in the space program was to use the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). The grants awarded to these bodies is in no way representative of achievement; quite the opposite, and Kersey notes that: “We could have been on Mars, but we had to pour billions of dollars into HBCUs.”

All along, you can feel the deep state battling desperately against the regular state, the one that wishes to use equal standards in a meritocracy and does not wish to hobble an organization as important to the American Dream as NASA. The media, the deep state’s provisional wing, wasted no opportunity in rubbishing the Apollo missions whenever they could. Gleeful media coverage emphasized the idea that the American flags planted on the Moon would have disintegrated. Undoubtedly so, said the producer of the famous flags. Symbolic of white failure, say the anti-white media.

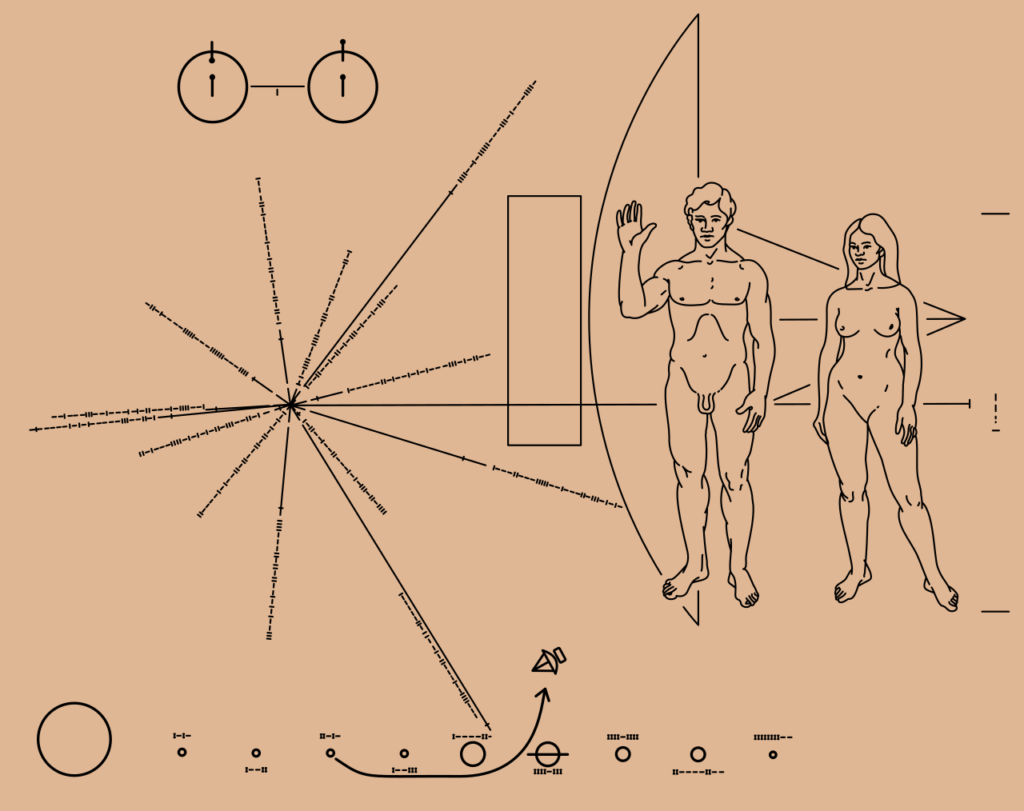

Speaking of space memorabilia, to add insult (ever-present for blacks in every white action or statement) to injury (ditto), when cosmologist Carl Sagan and some colleagues designed greeting plaques to be placed aboard the two Pioneer space probes that were destined for deep space in the early 1970s, they contained visual information for any curious alien eyes, including a figure of a man and a woman — a white man and a white woman. Cue the predictable black whining.

Blacks — and their fellow white travelers — also have an embarrassing tendency to grant fictional characters some kind of provisional status in the real world, and this tale is no exception. I wish I could find the YouTube video in which a Leftist tin soldier shows the evils of nuclear energy in part by showing Homer Simpson’s incompetence when left in charge of Mr. Burns’ (the greatest Simpsons character, in my view) power plant. Then there is Wakanda, which is believed to actually exist by many blacks. This was the reason Nichelle Nichols, the actress who portrayed Lt. Uhura in the original Star Trek series, somehow found herself as the spokeswoman for the black space race. She was flown in, literally, to add the glamor of television that many inexplicably find irresistible.

Since NASA folded under pressure, the focus of race agitation — and its Venn overlap with corporations under the gun of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion — has shifted subtly from “not enough blacks” to “too many whites.” But whites are still needed, if only to pick up the check for black dysfunction. How long this financial plate-spinning can continue is unclear. “What happens when a city no longer has enough white producers to fleece?” asks Kersey. And what happens when whites run out of money not just at an urban level, but at the national level? The ubiquitous Electronic Benefits Transfer cards, which are used and abused by blacks more than any other ethnic group, comes at a cost not born by the black community. Kersey makes it clear to whites who would rather not notice: “You’re paying for your own dispossession.”

[6]

[6]You can buy Greg Johnson’s It’s Okay to Be White here. [7]

WOTM’s conclusion is depressingly familiar to those familiar with Kersey’s work: Whatever societally undesirable effect exists, blacks suffer disproportionately, an outcome for which whites are ultimately responsible and for which they must continue to pay. The reasoning behind this wild claim? There is none given, for there is none to give.

And so as the deep states of the West try to erase our history and replace it with another, invented narrative, we must get it on the hoof, as we experience it or as our fathers experienced it, and before it is scribbled over. Blacks love to talk of the “black experience.” We need to counter this with the “white experience,” particularly of blackness (which is beginning to define us as whites), and this is where Paul Kersey comes in. History needs archives, and Kersey could rightly be called the archivist of black dysfunction, as well as indulging in a little useful accountancy during which he tallies up the white man’s financial burden when it comes to picking up the tab for endless black failure.

Quite why it was and is deemed necessary to dismantle and degrade white America is unclear. To take a Norman Rockwell painting and turn it into a Jackson Pollock takes a peculiarly high level of heartlessness, and the question of why the new global elites wish to destroy whiteness and its attendant culture remains unanswered, at least in full. But they have chosen their weapons wisely. Black dysfunction is an effective handicap of white progress, as Kersey’s book shows. In the end, there is a simple choice outlined in this latest chapter of black dysfunction and white culpability: “Detroit or the stars.” The American deep state chose Detroit.