Lent Observations

Posted By Richard Houck On In North American New Right | 8 Comments1,465 words

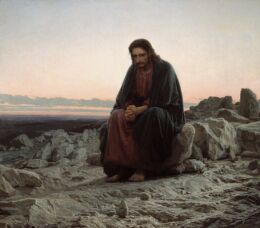

I started to seriously observe Lent with my grandmother on my mom’s side of the family about 15 years ago. She was Eastern Orthodox, and I am too – or at least I was baptized as such as a baby. On Fat Tuesday I usually stop eating around lunch. I fast on Ash Wednesday with no food, just water and black coffee. Then, sometime on Thursday I break the fast and start my Lenten restrictions (or Lenten sacrifice). My grandparents usually gave up meat for the entire 40 days, representing the 40 days Jesus Christ spent in the desert enduring constant temptation by Satan.

I must admit that I am not a very religious man in the traditional sense, or at least as that is commonly understood. I do not go to regular church services, read the Bible, or consult scripture or priests when I am dealing with difficult times. I am agnostic in relation to the Abrahamic traditions, if anything. With that said, I participate in the Orthodox traditions and Lent for many reasons, and I believe that others can relate to them.

Most major religions and belief systems that deal with the metaphysical or divine in some way incorporate fasting in their practices. The reasons for it will vary, but there is a common idea that it brings your physical body and mind closer to the esoteric and sacrosanct. Fasting in the Christian tradition is said to cleanse both the soul and mind. In Eastern beliefs, fasting is a way to more fully experience your existence and senses while heightening clarity.

Raising one’s mental clarity through fasting is something I have experienced profoundly. When I restrict my calories or go without food for long periods (usually 12-48 hours), my thoughts and senses all become extremely sharp. My sense of smell is heightened to a degree I did not know possible. I experience no “brain fog,” and I find staying on task is effortless. There is something about hunger that drives us to become better. Perhaps it is an old evolutionary survival mechanism: our brains becoming very clear and focused when we need to find food. It is also worth noting that the idea of being “hungry for something” in the abstract sense, such as for success or some other goal unrelated to food, is a phrase we often hear but do not fully consider in a society where there is constant access to food. If you fast for any significant amount of time, you will have a new appreciation for the term.

When we go without something, be it a specific vice or calories in general, its absence becomes known and abundant. I find I tend to appreciate things more when they are not always available, and I think most others do as well. The void it leaves ends up filling entire rooms.

During Lent I always find myself experiencing the gray shades of winter and the slow transition between seasons, both ecological and personal. I later learned that the Orthodox Greeks have a term for this: charmolypê. Like all great words that cannot be directly translated into English, it has many meanings: bitter joy, brilliant sadness, or a type of mourning mixed with happiness are all possible interpretations. A brilliant sadness is a good way to express how I felt when I lost my grandmother, who was my longtime film matinee companion and Lenten sacrifice partner, among much else. I lost her in the middle of Lent, which seems almost cosmic now as it is the season I associate most closely with her.

Lenten sacrifices are a perfect time to rid yourself of a bad habit or to form new and better habits. The time it takes to break or form a habit varies between people and the specific habits in question, but the average seems to fall at around two to three months. A study published in the European Journal of Social Psychology found a range of 18 to 254 days, with an average of 66.[1] [2] You may or may not fully break or make a habit in 40 days, but you will have a substantial start and will enter the Spring season with the groundwork for change laid. I am using this year’s season to limit the number of calories I eat per day to the minimum I need to function well while losing weight (about 1,700 per day), finishing up my cutting cycle to lose the last bit of fat I have before Spring begins. In essence, I am giving up any excess calories, which means I will not be enjoying pizza, pastries, beer, or soda, all things I take great pleasure in. There is not much else like being at the corner booth in a pizza shop on a Friday or Saturday night, listening to music while having a beer and soda with some food and friends. After Easter it will be that much better, which brings me to my next point about sacrifice, asceticism, and self-discipline.

[3]

[3]You can buy Jonathan Bowden’s collection The Cultured Thug here [4].

It stands to reason that if you can do or not do something for 40 days, you can continue well down that path for an untold number of months or years. Self-discipline is the foundation of all greatness, be it personal or on a civilizational scale. Without the ability to walk a careful path where one abstains from something now for greater benefit later, it becomes very difficult to build anything of substance, be it a fortune, a great physique, or a well-functioning civilization. There are choices we all make in life and as a society. A person can rarely spend frivolously and remain wealthy. It is likewise rare to indulge in every food craving and eat only the things one enjoys the most and maintain low body fat. We trade one thing for another, avoiding indulging in every desire in order to have something better later. In modern liberal society we often see short-term economic growth traded for long-term debt; the same goes for the short-term liberal “feel good policies” of being soft on crime and calling for open borders, which in the long term lead to less social stability and increasingly dangerous and crime-ridden cities. In another world, we might find it better to deal with the short-term backlash in reaction to illiberal policies that are harsh on crime and migration in the present for the future benefit of lower crime and greater stability.

Lent concludes on Good Friday, which commemorates the crucifixion of Christ; Holy Saturday, the day the body of Christ was laid in the tomb and He underwent the Harrowing of Hell; and finally Easter Sunday, the day of Resurrection. The fact that Easter falls near the Spring Equinox is similar to Christmas falling near the Winter Solstice. I can appreciate the many aspects of Easter even if I do not fully believe in them, from its pagan origins as a celebration of the spring goddess Ostara to the Christian celebration of the resurrection and rebirth of Christ. The relation of these traditions to each other and how they are practiced represents an interesting and often beautiful mix of the traditions of European peoples. The parallels between the rebirth of Christ and the return of the spring goddess are strong. Through the sacrifices made during Lent, we prepare the way for our rebirth as better men than when we started.

By Easter I will be far leaner than I was on Ash Wednesday. That means I will have a higher net worth, and with any luck on I will be on my way toward a better life. That’s how it has to be done, right? You make a decision and then take it one day at a time, day after day, letting all of the little changes and bits of progress add up over the years until one day you realize that it has added up to something magnificent.

My grandparents, all of whom are now gone, were very happy when I started to observe Lent traditions with them. At the time I was not sure why this was. I suspect they always knew I was not in fact moving closer to religion, but it was nevertheless a homecoming of sorts, being about tradition and the carrying on legacies and memories. It was something that brought us closer together. And in the end, that is how I’ve come to view all of Europe’s religious traditions. There is value in them, even if one is an agnostic who otherwise finds little value in the Abrahamic mythos.

I hope that all of you who observe it have a nice Lent.

Note

[1] [5] Phillippa Lally, Cornelia H.M. van Jaarsveld, Henry W.W. Potts, & Jane Wardle, “How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world [6],” European Journal of Social Psychology (July 16, 2009), Vol. 40, No. 6, pp. 998-1009.