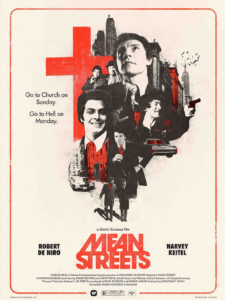

Mean Streets at 50

Posted By Mark Gullick On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled“You don’t make up for your sins in the church. You do it in the streets. You do it at home. The rest is bullshit and you know it.” — opening line of Mean Streets

Hollywood collapsed in the 1960s. It proved, if nothing else, that when it comes to big money, even Jews can screw up. A combination of anti-trust actions and the rise of television meant that studio lots fell silent, and the golden age of Hollywood was over. Fortunately a new generation of directors arose, bypassing the studio system and making movies in a way no one had ever done — because no one had ever thought to do so all the while the Hollywood machine was running at peak performance. One of the new movement’s earliest cinematic triumphs was Martin Scorsese’s breakthrough 1973 movie, Mean Streets.

These new kids on the block had their own heroes, the French auteurs of that country’s cinematic New Wave, along with similar trends in Italy and Britain. The fingerprints of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut are all over Mean Streets. Where Hollywood movies had developed a format based around separate, chapter-like scenes strongly visually established and all contributing to the development of a linear plot, the new techniques were looser, less structured, and often served to establish a mood rather than an unfolding narrative. There are a lot of scenes in Mean Streets of horseplay, fooling around, and dumb conversations which go nowhere.

One major reason Mean Streets got made was advice given to Scorsese by his hero and mentor John Cassavetes. Scorsese had debuted with the strong Boxcar Bertha in 1972, but Cassavetes told Scorsese he should make a picture which dealt with his own experience or else risk being locked into making cheap exploitation movies. Scorsese later referred to Mean Streets as “a declaration, a statement of who I am.” Who he was turned out to be a kid running around Little Italy with the other kids — Robert De Niro was in a rival street gang — soaking up an atmosphere which was a mixture of childhood rough-and-tumble, along with the darker side provided by the Mob.

Originally titled Season of the Witch, Scorsese felt the film’s eventual title — which has echoes of tough-guy B-movies and comes from a Raymond Chandler story — captured the mood of the tale perfectly. Roger Corman was so impressed he offered to fund the whole project if Scorsese moved the action from Little Italy and set it in the Afro-American community. Scorsese stuck with his vision until Jonathan Taplin, ex-road manager of The Band, stepped in with the whole budget of $600,000 (a little over $4 million today). Scorsese and The Band’s Robbie Robertson would become great friends.

On the subject of music, Mean Streets’ incidental score used a technique now familiar to moviegoers. In Goodfellas and Casino, Scorsese would go on to perfect the needle-drop “jukebox” feel to his soundtracks, and Mean Streets features memorable scenes heightened by the accompanying music — which is not background music, being upfront in the mix. Charlie, played by Harvey Keitel, wakes up after a troubled sleep to The Ronettes’ “Be My Baby.” De Niro’s character Johnny Boy swanks into a sleazy bar with a girl on each arm while The Stones’ “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” fills the air. Quentin Tarantino and Guy Ritchie owe a lot to Scorsese.

The four central characters each have a short establishing scene at the movie’s outset, and Scorsese shows he has already mastered a key technique of film writing and editing: economy. Establishing a character early is vital to a movie’s dynamic. In the 1966 film Harper, Paul Newman plays a hard-nosed, womanizing gumshoe — is there any other sort? — and we get a definitive glimpse into his life as, like Charlie in Mean Streets, he wakes up and begins his day. He goes to make coffee only to find the tin empty. He opens the trash can to reveal yesterday’s filter, full of soggy grounds. After a moment of inner struggle, Harper fishes it out and makes the coffee anyway. In that moment, we see his whole existence.

After the opening credits roll on Mean Streets, which run over a Super-8, home movie-style series of jump cuts featuring the main characters, the tone of the world in which these small-time gangsters move is set by a funfair cutting to a junkie fixing up in a filthy toilet, and the quartet of lead characters are shown in a montage. Bar owner Tony runs the junkie out and beats up his dealer. Next is gang boss Michael, overseeing some illicit transfer of goods between trucks before discovering that we he had thought was a consignment of German film lenses prior to purchase are in fact Japanese, and useless. A jaded look of bored disgust remains on his face for the whole movie. Next, we see De Niro as Johnny Boy, casually posting something in a mailbox. It turns out to be quite a powerful bomb, which blows the box to pieces as Johnny walks away. He doesn’t steal anything — there’s nothing left to steal — it’s just sheer devilment. When we get to Charlie, we find him in church, wondering how simple catechisms from a priest could possibly absolve a man of his sins, and brooding over the flames of Hell. He holds his finger in a candle flame, but doesn’t last long. “Pain in hell has two sides,” says his inner voice. “The kind you can touch with your hand, and the kind you can feel in your heart.”

[2]

[2]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here [3].

This is a main subplot of the movie. For Charlie, a theological question dominates: How does punk street morality square with divine providence? Charlie’s girlfriend Theresa, Johnny Boy’s sister, pulls him up short on the relationship between what he does and how he stands with his maker. Charlie has just expressed admiration for St. Francis of Assisi when she reminds him that “St. Francis didn’t run numbers.”

I always admired Keitel before his huge career boost in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, playing a hard-headed clean-up man who just so happens to clean up after grisly murders. He is outstanding as a police inspector obsessed with a suspect in Nic Roeg’s brilliant 1980 dysfunctional love story, Bad Timing. Jon Voigt was originally cast in the role of Charlie in Mean Streets, but delayed confirmation right up until the first day of shooting, when he dropped out, leaving the way free for Keitel.

Charlie’s metaphysical dilemma aside, the main tension in Mean Streets is the relationship between Johnny Boy and the excellent Richard Romanus as Michael. Johnny owes Michael money — a lot of money for the streets, especially with the infamous “vig” on top, the vertiginous interest. Charlie covers for Johnny and promises payment, at least in part. But not only does Johnny fail to come up with any money save a paltry $30, he openly taunts Michael [4]:

You know what, Michael? You make me laugh. I mean, I borrow money all over this neighborhood, from left and right, from everybody, and I never pay them back, so I can’t borrow no money from nobody no more, right? So who does that leave me to borrow money from but you? I borrow money from you because you’re the only jerk-off around here that I can borrow money from without paying back.

Michael wads up a $10 bill and throws it at Johnny, who gets out his Zippo and sets light to it. De Niro is laughing the whole way through, Romanus glowering, and it is Scorsese’s brilliance to make this scene crackle with tension.

At times, the film is funny despite its subject matter. The scene in which a fight in a pool room is started by one of the hoodlums calling another a “mook,” a word none of them knows the meaning of, is pure slapstick.

The influence of the French New Wave is once again evident in the camera work, and a lot of the movie was shot on hand-held cameras. This gives the mis en scène a feel best described as “unsteadicam” (Steadicam being a revolutionary camera-stabilizing system introduced to Hollywood in the late 1950s). In one scene, Scorsese gives a frighteningly accurate visual account of the experience of being utterly drunk [5] achieved by strapping the camera to Keitel’s body.

The code of the mean streets has many clauses, but one of the most important states that it doesn’t matter how capable you are at the job, if your friends are a problem, you become a problem, too — and Johnny Boy is a major liability for Charlie. The rest of the mob guys are reluctant to promote Charlie all the time he hangs around with the no-goodnik Johnny Boy. And the more Michael sees Johnny flashing the cash — his cash — at the bar, the more we feel the bloody denouement creeping closer. Like a Greek tragedy, hubris and nemesis are present and correct in Mean Streets.

I haven’t been to the movies in ten years. I’ve never even seen a cinema in Costa Rica; perhaps there’s an old Nickelodeon on a goat farm somewhere, I don’t know. But I still vaguely follow the cinema without seeing much more than trailers, and I wonder what type of movie gets made — is allowed to get made — nowadays. What does woke cinema leave you with? I watched The Deer Hunter again recently, and in the first, agonizing Russian roulette scene, I thought: They couldn’t make this now. Then I had an immediate second thought: Of course they could, and it would still be set in Vietnam. The difference would be that De Niro and Walken would be strapping, whiter-than-white camp commandants, and they would be forcing the gooks to play spin the barrel.

I can’t get out of this very American film without using a very American cliché: Mean Streets is a helluva movie. It’s a sock in the jaw, and, among other ground broken, it helped make movie violence visceral, more realistic than Hollywood’s usual one-shot deaths with a small bloodstain, which had yet become the absurd hail of automatic fire that sprays across today’s screens. This is street-level violence, and Peckinpah was waiting in the wings. Movie violence seems to have become a ballistic, graphic novel-style orgy now, from what I have seen of John Wick and his ilk.

If you are a Scorsese aficionado you will, of course, know Mean Streets. If not, it is one of the movies that made 1970s American film a new golden age of cinema.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [6]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall [7] page.