The Dakota Territory’s Indian Wars During the Civil War, Part 2

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,794 words

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here) [2]

The Galvanized Yankees

One of the regiments operating in the Dakota Territory during the Civil War was the 1st US Volunteer Infantry [3]. This regiment deserves a special mention because its story includes bringing former white enemies together who then went on to advance American civilization. Its soldiers were recruited from Confederate prisoners of war, and came to be called Galvanized Yankees. The regiment’s record is also an outstanding study of leadership under extremely difficult conditions.

The 1st US Volunteer Infantry was commanded by Colonel Charles Dimon [4]. Dimon was born in Connecticut and had worked as a bookkeeper. He enlisted as a private in Company J (Zouaves [5])[1] [6] of the 8th Massachusetts Infantry [7] two days before the Civil War-related riot in Baltimore [8]. The 8th Massachusetts deployed to the city and Company J was detailed to sail the USS Constitution from Baltimore to New York to ensure it wasn’t attacked by Confederate sympathizers.

This is one of many remarkable feats the Union Army [9] carried out during the Civil War: A company of infantry that had been hastily recruited and trained for actions on land could successfully deploy to a hostile environment and then serve as sailors on a ship. The modern US Army would not be able to carry out such a feat. The 8th Massachusetts was a 90-day regiment, meaning that enlistments were limited to 90 days, and Dimon mustered out with the rest of the regiment when its term ended.

Dimon’s abilities had been noticed by Major General Benjamin Butler [10], who commissioned him as a First Lieutenant in the 30th Massachusetts Infantry [11], where he deployed to Vicksburg, Mississippi. From Vicksburg, the 30th Massachusetts defended Baton Rouge against a a Confederate counterattack. Dimon was afterwards promoted to Major and sent to the 2nd (US) Louisiana Infantry [12], a regiment made up of local Unionists and former Confederate prisoners of war. Dimon mustered out after falling ill during the Siege of Port Hudson.

Once he had recovered, Dimon applied for a job on Butler’s staff, but the latter made several other counteroffers. Dimon settled for commanding the 1st US Volunteer Infantry, whose men were being organized at the POW camp at Point Lookout, Maryland [13]. Of the 1st Volunteers’ enlisted men, Historian Michèle Tucker Butts wrote that

. . . the average recruit [in the 1st US Volunteers] was like most other Civil War soldiers. He was a single, white dark-haired Protestant male in his mid-twenties who was born in the United States, and farmed to provide for himself. He resided in a low-to-moderate slaveholding rural county in the Piedmont or central portion of his home state.[2] [14]

Other ex-Confederates who joined the 1st US Volunteers were foreign-born men, mostly from Germany or Ireland, who had been working in the South when the war started and were then swept up into the Confederate Army. The German immigrants made rank quickly and soon comprised the backbone of the regiment’s senior non-commissioned officers. The regiment’s Sergeant Major was Herman Braun.

Of the commissioned officers, most were veterans of the 2nd, 5th, and 12th New Hampshire infantry regiments who had been serving as guards at Point Lookout. One exceptional officer was Second Lieutenant John Teske, formerly of the 3rd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery [15]. Colonel Dimon also secured commissions for his brother Benjamin and two other reliable men. Although he went to great lengths to pick good men as officers, some were still trouble — one was an embezzler, among other things –and were replaced over time. His most reliable officer was Major H. G. O. Weymouth [16], who was eventually picked to carry out staff assignments for the various higher headquarters, leaving Dimon scrambling to make up for the loss.

Captain Benjamin Dimon [17], Colonel Dimon’s brother, was a recovering [18] alcoholic [19]. He gave up drinking [20] at around the time the Civil War started. His example of temperance was a morale boost to the 1st US Volunteer Infantry, although few of the officers or enlisted men followed his example [21]. While in the Dakota Territory Captain Dimon carried out important assignments for his brother where he was operating independently from the regiment.

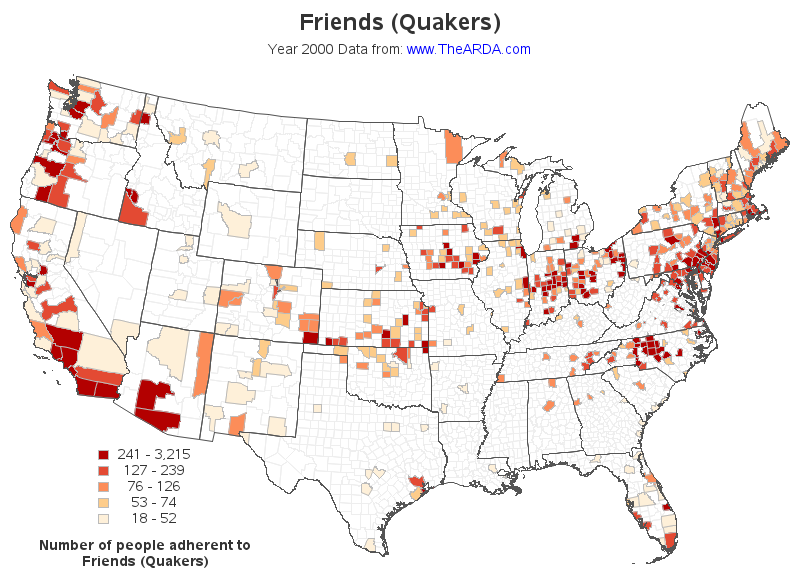

Of the native-born [22] American [23] Majority [24] whites [25] who enlisted, they mostly came from four Confederate states, especially North Carolina. The Tarheel State was an ambivalent star in the Confederate constellation. In the east the population was for succession, but in the mountainous west and central Quaker Belt [26], Unionist sentiment was very strong. North Carolina’s mountaineers were mostly Scots-Irish who owned few, if any, slaves.

[27]

[27]Many Quakers who settled in North Carolina had come from Pennsylvania prior to the American Revolution. Despite moving to a slave state, the Quakers there never entirely accepted the institution.

The Quaker Belt [28] contained Anglo-Quakers as well as Pennsylvania Dutch [29] Moravians, Dunkards, German Reformed, and Lutherans who had come to the region from Pennsylvania prior to the American Revolution. Daniel Boone, who was born near Philadelphia and was a Quaker, was part of this migration [30]. There were also many pro-Union Methodists in the area. Many of the Quaker Belt North Carolinians were encouraged to volunteer for the Union Army by Bryan Tyson [31], a Quaker from Randolph County.

Tyson wished to end the war and restore the Union via a middle way of unseating the Successionists and Radical Republicans in their elected offices. This failed to work, but he did distribute unionist tracts among the POWs at Point Lookout. His message was met with interest.

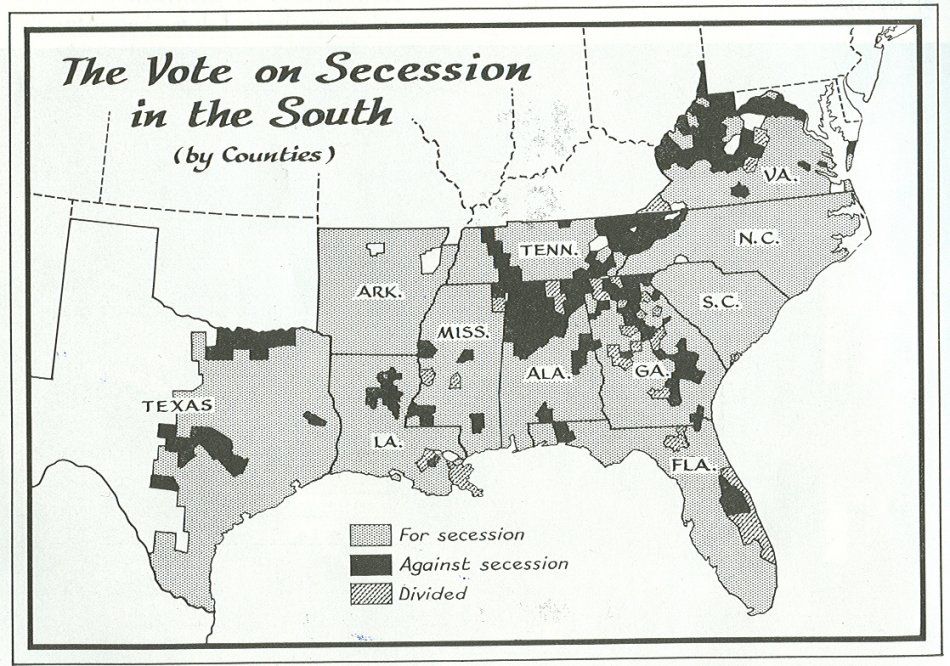

Another state the recruits came from was Tennessee [32], where the mountaineers in the eastern part of the state were pro-Union in the same way the mountaineers of western North Carolina were. The rest were from various parts of Virginia and Georgia. No recruits came from those counties of the Confederacy where sub-Saharan slaves made up the majority of the population. Those who lived around large numbers of sub-Saharans understood where the Radical Republicans’ disastrous policies would eventually lead.

[33]

[33]There were large areas of the South that were not in favor of secession in 1861. The men of these counties only served reluctantly in the Confederate Army. The Union Army successfully recruited entire regiments of men from those regions.

The 1st US Volunteers were sent to Norfolk, Virginia in mid-1864. There they conducted raids on suspected blockade runners and Confederate agents. They also raided into North Carolina and were involved in serious fighting there. One of the Galvanized Yankees captured by the Confederates was executed on the spot as a deserter, and another was never heard from again after being captured. Afterwards, General Ulysses S. Grant decided to transfer the Galvanized Yankees west to the Dakota Territory, where they would not have the additional risk of being executed if captured, and would not be forced to fight any family members or former neighbors.

[34]

[34]You can buy Tito Perdue’s novel Morning Crafts, here. [35]

On July 7, 1864, Brigadier General Sully selected a site in the Dakota Territory for Fort Rice in a strategic location between the mouth of the Cannonball River, Long Lake Creek, and the Heart River, all of which are tributaries of the Missouri. He left the 30th Wisconsin Infantry [36] to construct the fort’s buildings and continue his campaign. While the 1st US Volunteer Infantry was raiding North Carolina, Sully’s forces were engaged in the Battle of Killdeer Mountain in the Dakota Territory.

On August 15, 1864, the 1st US Volunteers left Norfolk for New York City. From there they went by train to Chicago, arriving on the 21st. In Chicago they received orders that companies A, F, G, and I would form an independent battalion and garrison Fort Wadsworth [37], which was near present-day Lake City, South Dakota, and Fort Ridgely [38]. Later, these companies would garrison strategic terrain on the Butterfield Overland stage route [39]. They mustered out on May 22, 1866, never having rejoined the rest of the regiment.

The remainder of the 1st US Volunteer Infantry headed on to Saint [40] Louis [41], where they proceeded by steamboat up the Missouri River to Fort Rice. The main problem on the voyage was preventing the men from deserting. Colonel Dimon eventually had a man shot by firing squad for attempting to desert on September 9. The execution was legal but fell outside the usual protocol. Dimon’s superiors didn’t comment on the matter, partially owing to the fact that the regiment was made up of ex-POWs, and white, working-class Southern men had become expendable — and nobody wanted desertions to continue.

The regiment had to disembark unexpectedly on September 22, as the Missouri River’s water level had gotten too low for further travel. The regiment was forced to march overland the rest of the way to Fort Rice. While on the march they slept in the open and endured rain and hail. On October 14 they met a band of Yankton Sioux led by Two Bears. This group had been fighting Sully’s column all summer, but now desired peace. This was a common practice of the Plains Indians throughout the Indian Wars [42]. In the summer, or whenever they saw fit, they’d be out murdering emigrants, settlers, and miners, but when winter would arrive, they’d head to the nearest US military installation, declare themselves peaceful, and draw rations through the winter.

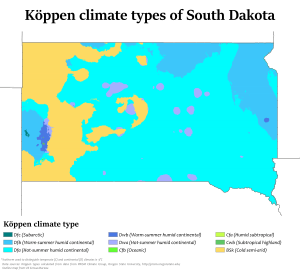

[44]

[44]South Dakota’s climate. During the Civil War, the two states were combined in a single territory.

The Galvanized Yankees arrived at Fort Rice on October 17, just before winter closed in. Freezing conditions soon closed the river to shipping. The regiment had enough supplies to survive the winter, although their food mostly consisted of rice, hardtack, and salted meat, especially ham. They also had three barrels of sauerkraut to ward off scurvy, but it wasn’t enough to last through the winter. Chronic diarrhea, fever, and scurvy were the main causes of death among the 1st US Volunteer Infantry [45].

The men were able to obtain fresh meat by hunting elk or bison, but it wasn’t until spring, when they were able to gather wild onions, that scurvy ceased to be a threat. Besides the unbalanced diet, the War Department hadn’t supplied the men with adequate warm clothing. The men made do as best they could, rotating the guard every 15 minutes during extreme cold. Frostbitten fingers and faces were common.

The Galvanized Yankees faced constant Indian attacks and had to be on guard at all times. They also had to secure emigrant trains, their own herd of horses and cattle, constantly improve and maintain the fort, and conduct diplomacy with friendly Indians when required. Colonel Dimon also went on a crusade against staff from the Indian Agency who were making deals with whiskey traders. This landed him in more trouble with his superiors than anything else. The agents were politically connected and didn’t like their illicit trading curtailed in any way. Then as now, there is always a subset of whites who profit from non-white pathologies while being connected to power structures.

The largest fight at Fort Rice occurred on July 28, 1865. Ironically, Colonel Dimon was away at the time, having been sent to consult with the military authorities in Milwaukee regarding Indian policy. In his stead was a veteran Lieutenant Colonel, John Pattee, [47] of the 7th Iowa Cavalry [48]. Fort Rice was attacked by surprise from three sides, but the garrison managed to drive the Indians off. Their hard work constructing a swivel for the post’s cannons and their hours spent on drill and training gave them the advantage.

The 1st US Volunteers was an outstanding regiment during the war. Its early successes prompted the raising of five other Galvanized Yankee regiments. Some Union states also recruited Confederate POWs into state-level organizations.

The regiment remained highly disciplined until early August of 1865. Since it was then deployed at the extreme edge of the Union Army’s logistical network, the War Department had a difficult time rotating troops in and out of Fort Rice. As a result, their mustering out was delayed, and this created considerable discontent. Ironically, the main “mutineer” at Fort Rice was a Yankee officer, Major Enoch Adams [49]. He was a Yale graduate and came from a prominent New Hampshire family, and was in fact older than Colonel Dimon. His career had been similar to Dimon’s, but Adams didn’t have as many connections to important men like Major General Benjamin Butler, so hadn’t made it to Colonel. Thus, resentment was undoubtedly part of the problem.

Colonel Dimon was in Kansas at the time after being promoted to brevet Brigadier General, as he had been ordered to take command of two regiments and demobilize them. He was called back to Fort Rice to deal with the discontent. When he arrived he put Adams and a few others under arrest of sorts. He sent the regiment on its way to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where they were due to be demobilized, in mid-October, after their replacements had arrived at Fort Rice. But when they reached Fort Leavenworth, General Elliott, the district’s military commander, decided the “mutiny” had been the result of petty grievances caused by the strain of being in a hostile frontier environment for so long. The arrests were thus lifted, back pay was settled, the final tranche of deserters was discharged dishonorably, and the regiment, minus the aforementioned detached companies, was demobilized on November 27, 1865.

The Dakota Campaign and beyond

While the rest of the Civil War was a brother’s war sparked by alleged concerns over the status of sub-Saharans on the part of self-righteous white virtue-signalers, the campaign in the Dakota Territory was a racial conflict, pure and simple. The Dakota Campaign was a bloody conflict between the Sioux, who had recently occupied the territory after arriving from Wisconsin, and American Majority whites. This war between the Americans and the Sioux, as well as other Plains Indians, continued until the 1890 Battle of Wounded Knee [50].[3] [51]

The tale of the Dakota Territory and the rest of the Upper Midwest’s settlement in the aftermath of the Civil War became the story which Americans told about themselves to the rest of the world for decades after the frontier closed. This story of conquest and settlement [53] also served to unite recent European immigrants with the old-stock Americans of both North and South. This myth likewise allowed all Americans to move past the Civil War and towards a future of innovation, prosperity, and space exploration. Theodore Roosevelt, who ranched in the Badlands of North Dakota near Medora [54] in the 1880s, led the way in this regard when he wrote that “[i]t is [in Dakota [55]] that the romance of my life began [56].” His book, The Winning of the West, was first published in 1889.

Hollywood played a role as well. By the end of the nineteenth century, Los Angeles became home to many transplanted Midwestern Americans. Their family stories became Hollywood’s stories [57], and the Western became a staple of American movies and television. Even the wildly popular Little House on the Prairie [58] is based on stories of the settlement of western Iowa, Minnesota, the Dakotas, and beyond.

[59]

[59]Civil War veterans in Valley City, North Dakota. The story of these veterans became America’s own narrative for decades to come. They proved their valor in a great yet tragic struggle, and then made the desert blossom as the rose alongside their wives.

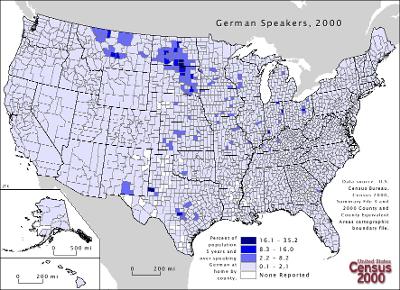

The Galvanized Yankees and men from Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin tamed a vast swath of territory safe for their kith and kind to live on forever after. The Galvanized Yankees, who had originally been North Carolina and Anglo-Pennsylvanian Quakers, as well as Germans [60] turned the west bank of the Missouri River in the Dakotas into an ethnostate. The area still has many German speakers today, as well as others whose origins stretch back to colonial Pennsylvania and New England.

[61]

[61]German speakers in the US Census of 2000. The area defended by the Galvanized Yankees during the Civil War became a place for the ethnocultural flourishing of Midland Americans, a heritage which many of the Galvanized Yankees shared.

The officers who led the Union Army in the Dakota Territory were nearly all Yankees with roots in New England. They turned Minneapolis, Sioux City, and Fargo into New England-style villages. It is up to us to ensure that this culture continues to survive and thrive.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [62].

Notes

[1] [63] Most Civil War regiments did not have a Company J [64], but the 8th Massachusetts did.

[2] [65] Michèle Tucker Butts, Galvanized Yankees on the Upper Missouri: The Face of Loyalty (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2003), 43.

[3] [66] The war between American Majority whites and the Sioux continued in other ways, however. Activists from the American Indian Movement were involved in a standoff with federal authorities in South Dakota in 1973, and for nearly ten months in 2016-17, Sioux activists organized a protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline in North Dakota. The ostensible reasons given for these actions were just excuses to make trouble for American Majority whites.