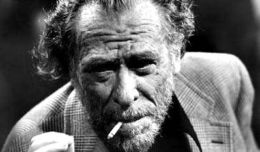

Not Pretending to Be Anything: Charles Bukowski

Posted By Mark Gullick On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledWhat matters most is how well you walk through the fire. — From an interview with Charles Bukowski

Sometimes the first lines of novels become as famous as the novels themselves. Think of some of the classics:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. — Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. — George Orwell, 1984

All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. — Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

Call me Ishmael. — Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

I am sure I didn’t need to give the provenance of these openers, as you’re a well-read bunch, but we don’t write only for those who know, but also for those who don’t yet know. And that’s the point. The opening line of a novel operates in the same way as the hook-line of a pop song in that it aims to drag you in, and to get you involved. The difference is that a novel demands a lot more of your time — which means a portion of your life — than a three-minute Beach Boys song.

First lines can be personal, however, as well as being in the literary commonweal. They can also fit the moment, as I discovered in 1994 in north London. I was managing the bar of a restaurant in the heart of Camden Town. I would work Friday nights, a double shift on Saturdays, and Sunday lunchtime. In return, the Uruguayan brothers who owned the restaurant gave me Mondays and Tuesdays off, and it became my weekend, to relax and to read. I had a competent deputy manager, and I knew he could keep things in order.

When I finished my Sunday shift, I would walk up in the direction of the London Zoo to Waterstone’s bookstore, the British equivalent of Barnes & Noble, and try to find something new and inviting to read. Then I would retire to one of Camden’s legendary pubs with my new book — The World’s End, perhaps, where The Clash used to drink, or The Devonshire Arms, favorite watering-hole of the late Amy Winehouse — and read the afternoon and sometimes evening away. One particular Sunday I walked into the bookstore and had two odd experiences. The first may be familiar to you.

Has your supermarket ever switched lanes on you? You go in on automatic pilot, same as always, to buy cheese or milk, go to the old familiar lane — or “aisle” in Britain, as though you are getting married — and are confronted with pickles or beer. The store manager has redesigned the lanes, and I am sure they do this either to push new or underperforming products, or just to annoy you. Maybe it’s just Head Office having fun. Well, the bookstore had done the same thing. I went robotically to where the philosophy section had been to find “Lesbian Fiction.” When I pivoted to the Classics section, it was now “The Beats.”

Perhaps it was grand design rather than redesign, because I paused in front of the Beats section. I had read Kerouac, but found him like gum which is delicious at first but quickly loses its flavor. I knew about the Merry Pranksters and I had read Ginsberg’s “Howl” at university — a waste of my time, frankly — the poem, not the university — but I found the whole thing a hippy charade, silliness masked by the pretense of these people being writers. And drug-influenced literature doesn’t work unless you are Samuel Coleridge or Thomas De Quincey. But I saw the spine of a book by a writer whose name I vaguely recognized. It was called Post Office and was by Charles Bukowski. I picked it out and read the first line: “It began as a mistake.”

[2]

[2]You can buy Mark Gullick’s Vanikin in the Underworld here. [3]

It seemed perfect, under the circumstances, and so I bought it, read it, and lost it the same night. I guess I just left it in the pub, or on the train or in a cab. I went back to the same shop the next day and bought another copy and read it again. I was served by the same girl as the previous day, and I could see her struggling with the problem of déjà vu. This copy I did not lose.

Henry Charles Bukowski was born in Germany in 1920 to an American father and German mother. He died of leukemia at the age of 73. He wrote six novels, many volumes of poetry, and became famous after his column, Notes of a Dirty Old Man, was published in Los Angeles’ Open City magazine, and later the LA Free Press. His celebrity fans include Sean Penn, Bono, Tom Waits, and Harry Dean Stanton.

There is little point in reviewing Bukowski’s novels, not because they are not worth it, but because the granite reality of the prose is the thing, not the plot. Post Office? A drunk guy works at a post office for 11 years and then quits. Factotum? A drunk guy drifts across America working various jobs. Women? A drunk guy makes some money writing and sleeps with more women than he used to. Bukowski’s narrative is relentlessly autobiographical, and the thread running through it is booze. Beer and wine, he wrote, is all there is.

Bukowski’s poetry readings were riotous. The poet himself needed so much beer during the performance that some promoters simply installed a refrigerator onstage, stocked it with Beck’s or Michelob, and let him help himself during the evening. Whether an alcoholic chooses his or her path, or whether they are created by their childhood, is of course a moot point.

Bukowski’s father would expect his son to cut the lawn as a weekly chore. Bukowski Senior would inspect the grass, and declare the job done badly. He would then flog his son with a razor-strop. Bukowski called this “good literary training.” If writers are created by suffering, Bukowski had his entry fee: “When you get the shit kicked out of you long enough, you have a tendency to say what you mean.”

Prose is interesting not just for its inherent beauty (provided that it is good), but also because of its personal provenance. Pure invention is wonderful; it induces a sense of wonder: Proust, Eco, even Harry Potter for the young, and science fiction certainly. But some writing comes not from the heart or the soul or the brain, but from the school of hard knocks. “Fiction,” wrote Bukowski, “is an improvement on life.”

Life didn’t exactly deal Bukowski a good hand of cards. As a boy he suffered from acne vulgaris, a far worse version of the acne we are familiar with either from childhood friends or ourselves, if we are unfortunate. Bukowski needed regular and horrible medical treatment to alleviate the condition. Later in life, this left “Buk” (one of his nicknames) with a shockingly pock-marked face. He was, it must be said — albeit without judgment — an ugly man. It would be hard to see how someone could portray him in a movie without specialist make-up. Mickey Rourke did a pretty good job.

Bukowski himself wrote the screenplay to Barfly, a 1987 movie starring Rourke as Bukowski and Faye Dunaway as his girl. Bukowski was generous in his appraisal of Rourke’s performance, with one proviso. In one scene, Rourke took a last swig from of a bottle of beer before he left the bar, but an inch or so of booze still remained. No true alcoholic, Bukowski said gravely, would ever do that.

Bukowski never hid from his alcoholism. “Forget my brother,” he said, “I am my own keeper.” This shows a sense of personal responsibility almost entirely absent in the modern world, where individual problems are always, always, someone else’s fault. Neither did he let his need to write go unexamined. Asked by an interviewer when he realized he was a writer, he replied:

“No one ever realizes they’re a writer, they just think they’re a writer.”

It looks cryptic and it looks glib, unless you are a writer. No one is a writer. You just write.

Bukowski drank, wrote, chased women, and went to the track. On one occasion, returning from a successful day at the races with $212 in his pants pocket, he looked down at his feet in the tram to see “One black shoe and one brown shoe. The light is dwindling, old boy.”

Bukowski is worth a day at the races. Read Post Office as an introduction, and you will know if you wish to proceed further. A successful writer and a successful drunk — if you can be said to succeed at the latter profession — he has no pretense anywhere near him. As Mickey Rourke says in Barfly, playing Henry Chinaski (Bukowski’s lifelong literary pseudonym for himself), “I’m not pretending to be anything. That’s the point.”

Who was Bukowski, as a writer? In his own words: “I’m just an alcoholic who became a writer so that I would be able to stay in bed till noon.”

Try it. You might like it.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [4]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[5]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[5]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.