Liberal Anti-Democracy, Chapter 1: How Western Elites Thwart the Will of the People

Posted By Kenneth Vinther On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled4,909 words

Part 1 of 9 (Chapter 2 here [2])

There is no doubt: the digital space has incredible power for good. But . . . we’ve also seen the threat it can pose to our democratic values, systems, and our citizens. — Justin Trudeau

I think it [the Internet] is the single biggest threat to our democracy. — Barack Obama

Genuine competition to determine who rules does not ensure high levels of freedom, equality, transparency, social justice, or other liberal values . . . democracy — if it exists at all — is illiberal. — Larry Diamond

Some on the dissident Right harbor a reflexive hostility towards the concept of democracy because they believe that popular government is responsible for the most catastrophic government policies of the last several decades: foreign military adventurism, globalization, social liberalism, and mass replacement immigration.

This is a fundamental misconception about the nature of our political system that gives it more credit and legitimacy than it deserves. By implying that the population asked for any of these policies, they transfer guilt from this corrupt political system onto its dispossessed European victims. It allows this system to gaslight and scapegoat its subjected European population, which never asked or voted for any of these policies. To suggest that this system enjoys majority support is to profoundly mischaracterize this oppressive regime. It also does us a massive disservice by causing the dissident Right to miss out on a tremendously powerful critique of liberalism.

To engage in a truly revolutionary critique, we need to dispel the myth of “democracy” that prevails in our society. The political scientist Christopher Achen calls this myth the “folk theory of electoral democracy.”[1] [3] This is the notion of democracy that prevails in public consciousness: the naïve idea that representative democracy “realizes the common good by making the people itself decide issues through the election of individuals who are to assemble in order to carry out its will.” It is the notion that democracy makes the people the rulers.[2] [4]

[5]

[5]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s The Tyranny of Human Rights here [6].

This theory has probably succeeded as a powerful cultural myth because it provides society with “a set of accessible, appealing ideas assuring people that they live under an ethically defensible form of government that has their interests at heart.” But unfortunately, this is not how electoral democracy “really works . . . or could ever work” in practice.[3] [7]

Contrary to popular belief, when political elites formulate government policies, they are not pandering to their voters by translating the preferences of the unwashed masses into government action. Numerous studies published in recent years have shattered this myth, illustrating that there is no substantive correlation between public opinion and public policy.

In their now-famous study, the political scientists Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page found that “the preferences of the vast majority of Americans appear to have essentially no impact on which policies the government does or doesn’t adopt. . . . The preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.” This was the same degree of correlation that you might expect “if policies were chosen by flipping a coin without any attempt to align them with citizens’ preferences.” Gilens and Page concluded that

the magnitude of this difference, and the inequality in representation . . . suggest[s] that the political system is tilted very strongly in favor of those at the top of the income distribution . . . The vast discrepancy . . . in government responsiveness to citizens with different incomes stands in stark contrast to the ideal of political equality that Americans hold dear . . . [America seems to be] antidemocratic . . . to the extent that it reflects the preferences of only a privileged subgroup of citizens.[4] [8]

Their results have been corroborated by numerous studies that have discovered “representational biases . . . [that] call into question the very democratic character of our society.” The political scientist Larry Bartels discovered that both major American political parties “are consistently responsive to the views of affluent constituents but entirely unresponsive to those with low incomes.” This is true not only with Congressmen but also with Senators, who “consistently appear to pay no attention to the views of millions of their constituents in the bottom third of the income distribution.” The influential political scientist Elmer Schattschneider also famously found that the “system is skewed, loaded and unbalanced in favor of a fraction of a minority . . . [It privileges] the most educated and highest-income members of society . . . [and exhibits a discernible] business or upper-class bias . . . [that] shows up everywhere.” In another recent study, Henry E. Brady and Kay Lehman Schlozman similarly concluded that “inequalities of political voice are deeply embedded in American politics.”[5] [9]

Despite appointing policymakers via elections, the majority of “average citizens exert little or no influence on federal government policy.” In one groundbreaking study conducted on Capitol Hill, the political scientists Lawrence R. Jacobs and Robert Y. Shapiro asked hundreds of members of Congress about how public opinion influences their policymaking. Their survey found that 88% of respondents admitted that public opinion “had no influence on the member.” Jacobs and Shapiro were forced to conclude that politicians from “both major parties [routinely] ignore public opinion and supply no explicit justification for it.”[6] [10]

Given the evidence, we are forced to conclude that the “folk theory of electoral democracy” is, “whether out of naïveté or disingenuousness, surely mistaken.” Public policy in Western liberal so-called “democracies” is not an accurate reflection of public opinion. Our so-called “democratic” system of government does not represent the will of the people. And this is because it is not designed to.[7] [11]

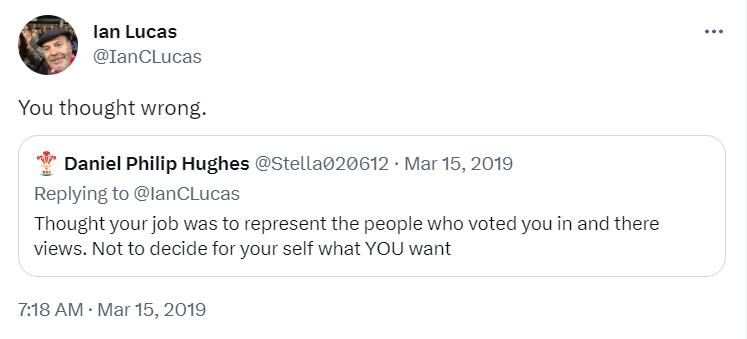

As Ian Colin Lucas, Member of Parliament for Wrexham, Wales, explained to one of his supporters [12] after expressing his intention to vote to overturn Brexit against the will of his constituents:

Daniel Philip Hughes: Thought your job was to represent the people who voted you in and their views. Not to decide for yourself what you want.

Ian Lucas: You thought wrong.[8] [13]

If you pay attention to the Western elites’ discourse, you will discover that they do not only consciously and routinely disregard public opinion, but they also harbor a vicious hostility towards it, identifying popular opinion as an obstacle that is fundamentally irreconcilable with their elite agenda. They believe that if public opinion were allowed to direct and influence government action, it would jeopardize many of their class objectives and policies, and so they viciously attack democracy and insist that Western elites continue to ignore and even oppose the preferences of their voting constituents.

Like virtually all modern regimes, from the Soviet Union to the “people’s democratic dictatorship” of Communist China, Western governments have historically justified their actions with vague appeals to democracy and the will of the people, decorating their policies with propagandic slogans like “the people have spoken” or “elections have consequences.”[9] [15] For a time, this tendency disguised the liberal elites’ antidemocratic sensibilities, making them at least appear to believe in some vague and sentimental principle of popular government. However, in recent years the phenomenon of populism has all but shattered this illusion, as popular challenges to liberal policy agendas at the ballot box have provoked a massive and hostile reaction against popular government throughout the Western world. It is no longer possible to ignore the profoundly elitist and antidemocratic character of Western liberal so-called “democracy.”

The western commentariat — i.e., the privileged analysts, policymakers, academics, and journalists who establish the parameters of the national political conversation — has refused to recognize any rejection of liberal internationalism at the ballot box, from Brexit to Trump, as a legitimate expression of democracy or the will of the people. Instead, the political class spiraled into a fugue of panicked hysteria, coalescing around a clear consensus: insurgent populist demagogues, and by extension their voting constituents, somehow represent a grave and existential threat to democracy itself. Some analysts have even argued that these political events signal the death of the “global liberal-democratic order.”[10] [16]

Grasping for explanations, some, like former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright — who stated on CBS’ 60 Minutes that the 500,000 Iraqi children killed as a result of American sanctions after the Gulf War were “worth it” — hysterically warn that populism signals the rise of fascism.[11] [17] French intellectual Jacques Attali attacked recent anti-liberal electoral outcomes as the “dictatorship of populism.” French socialite Bernard-Henri Lévy calls populism the “victory of the most rancid form of sovereignty and the most idiotic form of nationalism.”[12] [18] He believes that these movements represent an assault on “European civilization,” and that the very “legacy of Erasmus, Dante, Goethe and Comenius” is at stake. He is calling for European elites to organize and resist populism.[13] [19]

Intransigent and uncompromising, the Western liberal political establishment has churned out hundreds of articles and books under apocalyptic headlines, such as How Democracies Die; The Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism; In Defense of Elitism and Against Democracy; National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy; and Against Democracy and The Case Against Democracy, all of which claim that popular challenges to international liberalism at the ballot box somehow pose an existential threat to the very fabric of democratic society. In Anti-Pluralism: The Populist Threat to Liberal Democracy, William Galston argues that “populists damage democracy as such.” He believes that “the most urgent threat to liberal democracy is not autocracy; it is illiberal democracy.” The Brookings Institute recently published an article titled The Democratic Threat to Democracy, warning that popular majorities may coalesce around “illiberal” leaders to overthrow the liberal internationalist order.[14] [20] Johns Hopkins professor and Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) member Yasha Mounk, who calls populism both “a threat to liberal democracy” and a “disease,” recently published a book titled The People vs. Democracy.

[21]

[21]You can buy Greg Johnson’s The Year America Died here. [22]

At first glance, this discourse seems confusing. How can the people be against democracy? Doesn’t democracy mean “the rule of the people”? Is democracy not identical to the will of the people? This idea — i.e., the “folk theory of democracy” — is both the classical understanding of democracy as it existed as a political form in ancient Greece, and what ordinary people are thinking of when they talk about democracy today. However, this is not what Western elites mean when they say “democracy.” When Western elites are talking “democracy,” they are not talking about the “rule of the people” at all; what they are referring to is liberalism, or what they call “the open society.”

As Sean Illing and Zac Gershberg, authors of The Paradox of Democracy, explain, “the threats from disinformation, authoritarianism, and populist movements . . . [are] not threats to democracy in the way we typically think — they’re threats to a certain kind of democracy we’ve gotten used to over the past century.” Illing and Gershberg are not talking about democracy as “the rule of the people,” popular participation in politics, or free speech; instead, they are talking about liberalism, which means “the defense of minority rights, the rule of law, the peaceful acceptance of transfers of power, and all the institutions and cultural norms that sustain those things.”[15] [23]

“Even though they’re often mixed up together . . . [these values are] not inherent to democracy itself,” continues Illing. “Democracy and liberalism are [ultimately] very different things.” It is a “common mistake to conflate liberalism with democracy,” elaborates Professor Helena Rosenblatt, even though “[the] two concepts are not synonyms. For most of their history, they have not even been compatible.” This fundamental contradiction was submerged for a short time during the latter half of the twentieth century. However, in recent years this irreconcilability has become impossible to ignore. “Voters have long disliked particular parties, politicians, or governments,” explains Yasha Mounk. But “now, many of them have become fed up with liberal democracy itself,” and have started to reject these liberal norms and values at the ballot box. The Bush Center summarizes:

. . . for more than 75 years, the liberal international order purposefully constructed in the aftermath of World War II has helped secure peace, advance justice, and expand prosperity in the United States and around the world . . . Yet today that order appears to be under attack and at real risk of dissolving . . . In much of the Western world, we are seeing a rise in demagogic populism, illiberalism, nationalism, and protectionism. In short, fading confidence in the institutions of democracy and the market economy. Europe, in particular, is in deep crisis.[16] [24]

The central thrust of the “flourishing literature” discussing the so-called “crisis of democracy” boils down to a single complaint: “the problem with modern democracy is that the people have too much power.” The voting masses have been identified as a threat to liberal institutions, and Western elites consequently insist that ordinary people cannot be allowed to hold any sway over their political institutions.[17] [25]

In Too Much Democracy Is Bad for Democracy, Jonathan Rauch of the Atlantic argues that Donald Trump was elected because primary voters have too much power in the United States. For Rauch, “today’s system [of direct primaries] amounts to a radical experiment in direct democracy, one without precedent in America’s own political history” that has allowed extremists like Trump to “bypass” the traditional “professional gatekeeping” that party leaders and donors used to exercise over the nominating process. “Despite their flaws,” Milstein continues, “smoke-filled rooms did a good job of identifying candidates.” Milstein argues on behalf of reintroducing some sort of system of “professional vetting” or “nominating system” where insiders and party elites can supervise the political process and “act as gatekeepers against demagogues . . . charlatans . . . [and] antidemocratic candidates,” and “block . . . [candidates that] are unacceptable to the party or unfit to govern.”[18] [26]

“Our most pressing political problem today,” laments Rauch, “is that the country abandoned the establishment, not the other way around.” Recent political developments have demonstrated that “voters are very ignorant” and cannot be trusted to make important political decisions any longer. “Like it or not, most of what government does simply must be decided by specialists and professionals.” Andrew Sullivan of the New York Times argues paradoxically that “democracies end when they are too democratic.” The Friedrich Naumann Foundation summarizes:

Populism has become a widespread phenomenon throughout the world. The danger of their backward-looking nostalgia for an idealized past, half-truths and fake news stories pose a threat for free and open societies.

In a style reminiscent of Henry Kissinger’s nakedly elitist treatise World Order, James Traub declares from the CFR’s flagship magazine Foreign Policy: “It’s time for the elites to rise up against the ignorant masses.”[19] [27]

Searching for solutions, some, such as Sławomir Dębski, believe that populism is a temporary phenomenon, a mere setback that will eventually blow over: “In the meantime, democracy must adopt strategic patience.” Others are more concerned, however, and insist that elites need to implement more aggressive solutions to address this problem.[20] [28]

Many liberal elites in this debate have interpreted populism primarily as a backlash against the radically unequal distribution of wealth facilitated by neoliberalism. Because they perceive the problem to be economic in nature, most commenters prescribe economic solutions to resolve this crisis. Barry Eichengreen argues that the welfare system was insufficiently “equipped to deal with the economic fallout that attended globalization and the decline of manufacturing in America.” He does not suggest reforming our system to be less detrimental to the majority, but instead suggests that welfare systems simply need to be improved. Mounk agrees, urging governments “to find the courage to redesign welfare states in a radical way.” Others like Daniel Ziblatt have similarly argued that the solution is to “address the issue of inequality” with “a much more aggressive raising of the minimum wage, or a universal basic income,” and to introduce other piecemeal reforms to Social Security and Medicare to create better safety nets to catch the losers who were left behind by our brave new deindustrialized global marketplace.[21] [29]

But others such as Eric Kaufmann, the author of Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration, and the Future of White Majorities, have pushed back against these economic interpretations: “It’s NOT the economy, stupid.” Instead, Kaufman argues that the major impetus behind events like Brexit and Donald Trump is the anti-immigrant attitudes of white Americans and Europeans who fear their impending demographic replacement, and a rejection of the liberal internationalist ideology of Western institutions more broadly. According to Kaufmann, populism should be interpreted as a reaction against the extreme liberal

norm innovation [that has become] lodged in the DNA of elite institutions, government agencies, corporations and much of the media, [where] “truths” like “systemic racism” or “speech is violence” [have] become sacred values that cannot be questioned by evidence. Today there is still a struggle to be had, so left-modernist radicals are fighting to consolidate their grip on the ethos of institutions through advertising boycotts, Twitter mobs and internal staff activism. As under Maoism, once compromised, institutions compete to outdo each other in exemplifying left-modernism’s values.[22] [30]

Kaufmann argues that to quell the fires of populism, it is incumbent on elites to moderate their policies slightly to reduce popular backlash and make the transformation towards multiculturalism more sustainable, such as by lowering immigration rates to allow for “a slower rate of change to enable assimilation to take place.” Similar arguments have also been made in the past by figures such as Stephen Steinlight, former Director of National Affairs of the American Jewish Committee, who argued that Jewish elites should abandon their traditional support for mass immigration and adopt “a pro-immigrant policy of lower immigration” due to his belief that excessively high rates of immigration might provoke a nationalist backlash that could threaten minorities such as the Jewish community in the West.[23] [31]

[32]

[32]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Here’s the Thing here. [33]

Nevertheless, others, such as Sean Illing and Andrew Marantz, are not particularly concerned with what it is that is motivating populism and illiberalism in the West. Whether it is economic precarity or a backlash against immigration, to them the question is immaterial; they instead believe that the salient problem is why illiberal, anti-immigration sentiments have been given any space in the political discourse in the first place. For them, the problem with our society is the democratic tradition of free speech, particularly as it existed briefly on the social media platforms that facilitated historically unprecedented levels of information sharing and free discussion in recent decades.

In his book Antisocial: Online Extremists, Techno-Utopians, and the Hijacking of the American Conversation, Andrew Marantz “laments the fall of the journalistic ‘gatekeepers’ who used to arbitrate public discourse.” He traces the problem to the philosophy of “what businesspeople like Thiel called disintermediation” that was embraced by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs in the early 2000s. Looking at the internet from a business perspective, “getting rid of informational gatekeepers seemed like a no-brainer.” Andrew Bosworth, one of Facebook’s chief engineers, explained Facebook’s growth strategy: “We connect people. Period.” As Mark Zuckerberg explained,

many of us got into technology because we believe it can be a democratizing force for putting power in people’s hands. I believe the world is better when more people have a voice to share their experiences, and when traditional gatekeepers like governments and media companies don’t control what ideas can be expressed.[24] [34]

But as opposed to the term “disintermediators,” Marantz prefers to call these entrepreneurs — a group that includes people from Mark Zuckerberg to Emerson Spartz, Paul Graham, Steven Huffman, and Alexis Ohanian — “disrupters,” because they failed to foresee how “removing the gatekeepers, without any clear notion of what might replace them, could throw the whole information ecosystem into chaos.” He claims that they eventually learned this lesson the hard way when “trolls and reactionaries . . . ‘hijacked’ democracy,” and Trump rode the energy generated by the alternative online information ecosystem into the White House in 2016. Reflecting on events two years later, Mark Zuckerberg himself expressed regret for having contributed to the problem by enthusiastically embracing disintermediation on his social media platforms:

The past two years have shown that without sufficient safeguards, people will misuse these tools to interfere in elections, spread misinformation, and incite violence . . . One of the most painful lessons I’ve learned is that when you connect two billion people, you will see all the beauty and ugliness of humanity.[25] [35]

“[F]ree speech is killing us,” laments Marantz. He argues that the solution to the “crisis of democracy” is for social media platforms to aggressively regulate and censor speech and discourse online. He urges tech entrepreneurs such as Zuckerberg to “make Facebook slightly less profitable and enormously less immoral . . . by hir[ing] thousands more content moderators and pay[ing] them fairly” to police speech on the platform. Per Marantz, protecting the liberal order and quelling the rise of populism means heavily censoring online speech and restoring “our media gatekeepers” — who conveniently happen to be “coastal, secular, educated at a handful of elite universities . . . [and] suffer from profound myopias and bias” — that kept the national political discourse within acceptable liberal parameters up until the Trump presidency.[26] [36]

Other commentators argue that even more repressive and authoritarian measures are needed to control the situation by using the state to police and suppress “extremist” Right-wing political opinions and anti-immigration attitudes. Daniel Ziblatt, author of How Democracies Die, suggests that

we should begin to think about the idea that Germans in the postwar period called “wehrhafte Demokratie” — this is a “defensive democracy” — one that embraces the inclusion, competition, and civil liberties of liberal democracy but one that doesn’t take democracy for granted. In Germany, the theory of “defensive democracy” had two main thrusts — one is the attempt to bolster a democratic political culture through education, and the other is an aggressive willingness to isolate and exclude from political debate those views that endorse violence and that actively engage in violence. This doctrine was invented in the 1930s in response to Nazism. We may, ultimately, need a “wehrhafte Demokratie” for the social media age.[27] [37]

The blatant and authoritarian political repression in Western Europe, and increasingly even in America, has led to a comical situation in which illiberal authoritarian regimes such as Turkey and Russia have started to imitate the justifications used by Western countries when persecuting political dissidents. This has created a dilemma for Western liberal democracies, who are finding it difficult to criticize these authoritarian regimes for violating the civil liberties of political opposition groups because they are using equally authoritarian and repressive measures to defend and enforce liberalism domestically. “When illiberal regimes argue that they’re simply taking militant democratic measures like banning a ‘terrorist’ party,” explains Mika Hackner of the Washington Post, “sincere militant democracies have less credibility in criticizing their actions.”[28] [38]

Obviously, Western elites seem hypocritical when hysterically screeching about the populist threat to civil liberties, the rule of law, and opposition rights while simultaneously violating these very same democratic rights of their illiberal political opponents and critics. This is not a contradiction for the Western elites, however, because the Western elites are not actually committed to democracy at all.

The political scientist Sheldon Wolin once remarked that the way these concepts hold sway with liberal elites reveals how they harbor a profound antipathy towards majoritarianism and popular participation in politics, and would gladly abandon democracy to preserve the trappings of liberalism. Time editor and CFR board member Fareed Zakaria, protégé of Samuel Huntington, argues in his book The Future of Freedom that “the rule of law, a separation of powers, and the protection of basic liberties of speech, assembly, religion, and property . . . [have] nothing intrinsically to do with democracy.” He notes that

in the United States slavery and segregation were “entrenched” by virtue of “the democratic system.” Jim Crow was destroyed, Zakaria opines, not by democracy “but despite it.”[29] [39]

Zakaria’s writing betrays a predilection for a hierarchical and closed political system, and a preference for a “secular” or “tolerant” liberal dictatorship under a despot like Tito, Suharto, Musharraf, or Pinochet over an authentic democracy, which he fears has an inherent tendency towards illiberalism. Zakaria shares this opinion with neoliberals of the past such as Friedrich Hayek, who once professed that he would “prefer a liberal dictator to democratic government lacking liberalism.” The same has also been professed by other influential “libertarian-leaning liberals such as Bryan Caplan, Jeffrey Friedman, and Damon Root [who] believe that when democracy threatens the substantive commitments of liberalism . . . it might be better simply to consider ways to jettison democracy.”[30] [40]

Exemplifying elite liberal attitudes in the post-war era, the influential American political theorist Robert Dahl famously stated that “democracy cannot be justified merely as a system for translating the raw, uninformed will of a popular majority into public policy.” For liberal elites, liberal democratic institutions have nothing at all to do with the rule of the people. Rather, to them liberal democracy is simply “a set of rules and procedures, and nothing but a set of rules and procedures, whereby majority rule and minority rights are reconciled into a state of equilibrium.” Democratic institutions exist solely as a series of “mechanical arrangements” for defending minority rights and perpetuating elite liberal values. “If everyone follows these rules and procedures,” Irving Kristol explains, “then a democracy is in working order.” However, if these democratic procedures begin to conflict with or threaten these liberal priors, then they have outlived their usefulness, and liberal elites will be entirely willing to discard the foundational institutions of democracy, such as free speech, if it is necessary for defending the broader liberal internationalist project.[31] [41]

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [42].

Notes

[1] [43] Christopher H. Achen & Larry M. Bartels, Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government (Princeton University Press, 2017), 9.

[2] [44] Joseph Schumpeter, quoted in Achen & Bartels, 22.

[3] [45] Achen & Larry Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 1; George Monbiot, “Lies, fearmongering and fables: that’s our democracy [46],” The Guardian, 2016.

[4] [47] Martin Gilens, Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America (Princeton University Press, 2012), 1; Martin Gilens & Benjamin I. Page, Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens (Cambridge University Press: 2014), 575; John G. Matsusaka, Let the People Rule: How Direct Democracy Can Meet the Populist Challenge (Princeton University Press, 2022), 54; and Gilens, 70.

[5] [48] Martin Gilens, “Public Opinion and Democratic Responsiveness: Who Gets What They Want from Government?”, Public Opinion Quarterly, 2005; Larry M. Bartels, Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age, second edition (Princeton University Press, 2008), 267-268; Elmer Eric Schattschneider, A Semisovereign People (Dryden Press, 1975), 34-35; and Kay Lehman Schlozman, Sidney Verba, & Henry E. Brady, The Unheavenly Chorus: Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy (Princeton University Press, 2012), 8.

[6] [49] Martin Gilens & Benjamin I. Page, Democracy in America?: What Has Gone Wrong and What We Can Do About It (University of Chicago Press: 2020), 68; and Robert Y. Shapiro & Lawrence R. Jacobs, Politicians Don’t Pander: Political Manipulation and the Loss of Democratic Responsiveness (University of Chicago Press: 2000), 268, xiii-xviii.

[7] [50] Kay Lehman Schlozman, Sidney Verba, & Henry E. Brady, 575.

[8] [51] Ian Colin Lucas, tweet, March 15, 2019, 7:18 AM, https://twitter.com/IanCLucas/status/1106545273118052352 [12].

[9] [52] Constitution of the People’s Republic of China [China], 4 December 1982, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4c31ea082.html [53].

[10] [54] Ed Pilkington, “‘Our democracy is deeply imperiled’: how democratic norms are under threat ahead of the US election [55],” The Guardian, 2020; John Cassidy, “Trump Represents a Bigger Threat Than Ever to U.S. Democracy [56],” The New Yorker, 2020; and Uri Friedman, “Democrats Have Found Their Battle Cry [57],” The Atlantic, 2019.

[11] [58] Madeleine Albright, Fascism: A Warning (Harper: 2018).

[12] [59] Quoted in Greg Johnson, “In Defense of Populism [60],” Counter-Currents, 2020.

[13] [61] Quoted in Lara Marlowe, “‘A new battle for civilisation’: Bernard-Henri Lévy’s war on populism [62],” The Irish Times, 2019.

[14] [63] Kemal Derviş, “The democratic threat to democracy,” The Brookings Institute, 2022.

[15] [64] Sean Illing, “Free speech is essential for democracy. Could it also be democracy’s downfall? [65]”, Vox, 2022.

[16] [66] Helena Rosenblatt, “Liberal democracy is in crisis. But … do we know what it is? [67]”, The Guardian, 2018. Yascha Mounk, “How populist uprisings could bring down liberal democracy [68],” The Guardian, 2018. Thomas Melia, “The Spirit of Liberty: At Home, In the World [69],” George W. Bush Presidential Center, 2017.

[17] [70] John G. Matsusaka, 56.

[18] [71] Jonathan Rauch & Ray La Raja, “Too Much Democracy Is Bad For Democracy [72],” The Atlantic, 2019.

[19] [73] Jonathan Rauch, “How American Politics Went Insane [74],” The Atlantic, 2016; Jonathan Rauch & Benjamin Wittes, “More professionalism, less populism: How voting makes us stupid, and what to do about it [75],” Brookings Institute Center for Effective Public Management, 2017; Andrew Sullivan, “Democracies End When They Are Too Democratic [76],” New York Magazine, 201; Friedrich Naumann Foundation, quoted in Thomas Frank, The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism (Metropolitan Books: 2020), 3; and James Traub, “It’s Time for the Elites to Rise Up Against the Ignorant Masses [77],” Foreign Policy, 2016.

[20] [78] Global Memo, “The State of Democracy in 2020: Crisis or Renewal? [79]”, The Council of Councils, 2019.

[21] [80] Barry Eichengreen, The Populist Temptation: Economic Grievance and Political Reaction in the Modern Era (Oxford University Press: 2018); Yascha Mounk, The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It (Harvard University Press: 2018), 231; and Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky, How Democracies Die (Crown: 2019), 228.

[22] [81] Eric Kaufmann, “It’s NOT the economy, stupid: Brexit as a story of personal values [82],” London School of Economics, 2016; Eric Kaufmann, “The Great Awokening and the Second American Revolution [83],” Quillette, 2020; and Eric Kaufmann, “How Progressivism Enabled the Rise of the Populist Right [84],” Quillette, 2019.

[23] [85] Isaac Chotiner, “A Political Scientist Defends White Identity Politics [86],” The New Yorker, 2019; and Stephen Steinlight, “The Jewish Stake in America’s Changing Demography: Reconsidering a Misguided Immigration Policy [87],” Center for Immigration Studies, 2001.

[24] [88] J. Oliver Conroy, “Antisocial review: Andrew Marantz wades into the alt-right morass [89],” The Guardian, 2019; and Andrew Marantz, Antisocial: Online Extremists, Techno-Utopians, and the Hijacking of the American Conversation (Penguin: 2019), 48.

[25] [90] Andrew Marantz, 50.

[26] [91] Andrew Marantz, “Free Speech Is Killing Us [92],” The New York Times, 2019.

[27] [93] Sean Illing, “The central weakness of our political system right now is the Republican Party [94],” Vox, 2021. See also John Powell, “Opinion: Democracy Against The People [95],” National Justice, 2021.

[28] [96] Mika Hackner, “Germany has banned political parties in the past. Can it credibly condemn Turkey for doing the same? [97]”, The Washington Post, 2021.

[29] [98] Sheldon S. Wolin, Democracy Incorporated: Managed Democracy and the Specter of Inverted Totalitarianism (Princeton University Press: 2017), 175.

[30] [99] Patrick J. Deneen, Why Liberalism Failed (Yale University Press: 2018), 157.

[31] [100] Dahl, quoted in Robert Y. Shapiro & Lawrence R. Jacobs, 298. Kristol, quoted in Alain de Benoist, The Problem of Democracy (Arktos: 2011), 62.