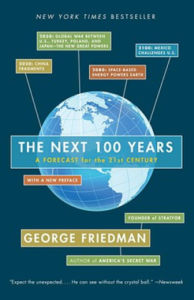

George Friedman’s The Next 100 Years

Posted By Thomas Steuben On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledGeorge Friedman

The Next 100 Years: A Forecast for the 21st Century

New York: Anchor Books, 2009

George Friedman’s The Next 100 Years is an intriguing forecast of how the twenty-first century will play out. Friedman gets a lot of things wrong, but there is nevertheless a method to his analysis, and we have much to learn from what the broader center-Left, of which Friedman is a part, gets right. It’s also interesting because glowing reviews in the mainstream media suggests that the book has been guiding the establishment’s thinking, and thus explains some of their odd decisions.

The author has limitations, however. He comes from a Jewish family who escaped Communist Hungary, and this seems to account for his obliviousness to racial issues and failure to delve deep enough into cultural issues, along with his optimism concerning the United States. This seems to be the result of naïveté as opposed to bad faith, however, which is a refreshing change in 2023.

In this book Friedman epitomizes the old center-Left, which I may disagree with but could at least respect. The Next 100 Years was published in 2009 — a time when Barack Obama opposed gay marriage and there was exuberant talk of a post-racial America. His predictions, while well-reasoned, seem trapped in a past era that seems almost as remote as the Austro-Hungarian Empire is to us today. The book was thus more suggestive of nostalgia than futurism for me.

While Friedman is still ultimately a progressive, his observation that there is a cyclical rhythm to the United States’ crises shows that he rejects the arrogant “end of history” paradigm. Additionally, Friedman’s view of geopolitics is that world leaders, despite appearing to have a lot of power, are actually quite constrained in the choices they can make. This is akin to how master chess players know their options better and are thus more constrained than novices, as they are ironically easier to predict.

This leads to some weaknesses in Friedman’s approach. What if some of the players are being given bad information, such as how Vladimir Putin was led to underestimate Ukraine’s tenacity? What if some of the players are mentally unstable, or have unconventional goals? Donald Trump kept the peace in part by being — or at least appearing to be — unstable.

Also, consider that there are different paths to victory, hidden agendas, and the like in board and computer games. These games are as informative as they are amusing because art imitates life. The US regime’s doubling down on the transgender agenda at home and abroad is very similar to a team in a game that pursues a victory condition of “paint the map X% ideology or religion.” While world leaders are usually rational, they are nonetheless human, and thus not immune from the same sort of emotional pettiness that board games tend to bring out in even the most cool-headed of players.

Furthermore, Friedman says he appreciates culture, but he does not seem to follow through in appreciating it quite enough, or by recognizing that there is human agency behind cultural changes. For example, he claims that traditional family values are changing simply because of economic reasons. This is patently incorrect, as the Jews are notorious for continually undermining family values, either for shekels or simply out of an ethnic animus.

He likewise correctly identifies that declining birth rates are the single most important demographic fact. Friedman predicts that the developed nations will begin competing against each other to attract immigrants for economic reasons, and that those who come from the Third World will assimilate just as previous waves of immigrants did because they will be scattered across their new nations rather than physically attached to their old countries or concentrated in a borderland (he makes an exception for Mexicans, but solely because Mexico is contiguous with America). We of course understand that this is a recipe for the Great Replacement and tumbling national IQs, even if the new immigrants actually do assimilate, which experience has shown to be unlikely.

Sadly, Friedman’s analysis is limited given that it does not account for race realism. While not technically immigrants, blacks have yet to assimilate into American society despite numerous efforts at integration. Even if they have higher IQs, new immigrants are just as foreign as blacks and cannot be expected to assimilate, either. Friedman’s optimism about this being an American century is therefore faulty because it is based on the idea that the US will outcompete other countries in attracting immigrants and then assimilate them.

One of the points Friedman does make correctly is that the US is not great because of its founding documents, but because it has vast natural resources, access to two oceans, and emerged from the Second World War unscathed while its competitors were bombed into rubble. Such realism is a nice reprieve from constitutional chauvinism, which fails to take into account the fact that Liberia’s constitution is a copy of America’s, and yet it hasn’t followed the same path to success. Regardless, given recent events I am doubtful that these advantages alone will be enough to maintain America’s dominance for another decade, let alone the rest of this century.

[2]

[2]You can buy Christopher Pankhurst’s essay collection Numinous Machines here [3].

The US is a victim of its own success. The advantages Friedman rightfully identifies allowed the US to enjoy a wide margin of error in its policies, as the author himself admits. Less powerful countries have to be far more careful, because a small mistake can be disastrous for them.

The problem is that America’s ability to make wise decisions has atrophied from lack of use. This is akin to the fact that while a millionaire usually has good judgment, his descendants often do not, even if they inherit his wealth. This decline, when added to the fact that America has been growing increasingly culturally abrasive, has annoyed most other countries to at least some extent. Friedman thinks that decades will pass before these realities catch up with the US, because no other country wants to be the nail that sticks up and is then hammered down by the world’s policeman. Nevertheless, Iran’s recent rapprochement with Saudi Arabia shows that other countries are willing to put long-standing resentments aside when it’s to their mutual advantage. And after the Taliban’s triumph in Afghanistan, not to mention the US visibly losing domestic support for its policies, the rest of the world knows that American boots on the ground are much less likely today.

America’s prime strategy for maintaining its dominance for so long has been not to “win,” but to prevent others from winning. This explains why the US establishment always appears unfazed by disasters such as the Vietnam War, Iraq falling to Iranian influence after a costly US invasion, or the fall of Kabul to America’s sworn enemies. Like the British Empire, America’s goal as a sea power is to prevent any other power from becoming too strong. This is not an effective long-term strategy, however, as It relies on the fact that none of the other players will ever find a way to become a genuine threat. Imagine a player in a board game whose strategy consists entirely of disrupting the other players’ strategies. He would quickly anger the entire room, and cause his opponents to work together against him.

Such a policy is moreover demoralizing on the home front, as it never offers any real sense of national accomplishment despite the sacrifices the people are expected to make in blood and treasure. It rather causes the regime to be simultaneously despised for its tyrannical injustice as well as its ineptitude.

Friedman predicts, from the point of view of 2009, that the “War on Terror” would eventually dissipate given that America’s actual strategic goal was not the elimination of Islamic extremism but rather to prevent the ideology from uniting the Islamic world. Friedman was correct about this, even though he does not entirely concede that the “War on Terror” itself was primarily instigated by the US itself. While Islamic extremism seems less threatening today than it did then, it nevertheless feels like a pyrrhic victory given the price we had to pay, both materially and in terms of humiliation, not to mention how it damaged America’s relations around the world.

Friedman is also correct in saying that the War in Iraq was insignificant in terms of the casualties inflicted on the US and its allies. What he neglects to add is that the fact that the war divided the country so deeply is a sign of the US rotting from within. The regime no longer has a positive vision with which to inspire its citizenry, aside from vague nonsense about spreading human rights. The costs likewise fell disproportionately on a small portion of the country that has grown tired of sweating and bleeding for the Washington elite.

Friedman rightfully says that America’s sometimes apparently odd behavior as a nation can be partially explained by the fact that it is a young country. Like a stereotypical teenager, it is both arrogantly headstrong while also full of self-doubt. But there are other factors as well, such as the fact that much of the ruling establishment is Jewish, and thus neurotic. Also, while the US as a nation is young, it is nevertheless also part of the Faustian West, which, as we know from Oswald Spengler, is in its civilizational winter. National immaturity, civilizational senility, and Jewish neuroticism is a perfect combination for making poor geopolitical decisions.

Similar to his analysis of the Iraq War, Friedman is half correct in saying that, from an objective perspective, the 2008 market crash was not that severe. What he fails to mention is led to a dramatic increase in the ever-widening wealth gap. The Century Foundation reported several metrics in 2013 [4] by which the wealth gap had dramatically increased as a result of the 2008 crisis. Today, wages are lagging so far behind inflation — especially in relation to housing — that many people do not feel that it is worthwhile any longer to work hard and contribute to society. The effects of this range from shoddier work to people becoming addicts or perpetual NEETs (not in education employment or training). Meanwhile, society’s upper crust has grown openly hostile towards the very same people they refuse to pay decently. The legacy of 2008 thus cannot be understated, because it was the turning point at which home ownership, the ability to start a family, and other activities once taken for granted began to be out of reach for ordinary Americans. As a result, the Atlas of the white worker is beginning to shrug.

Many of Friedman’s errors are reasonable errors for the time, however, such as that he miscalculated by thinking that Russia would splinter apart and China would be at risk of splintering if the US did not artificially prop them up. He also posits that China will eventually become more dependent on the US than vice versa. Despite taking culture seriously, it was a lack of understanding of culture which led to his miscalculations.

First, while Russia might be a multi-ethnic hodgepodge, its peoples are accustomed to and even welcome imperial despotism. China is similar. Although, as Friedman points out, China has a history of bloody rural rebellions against its coastal elites, it also has a long history of submission to authority.

Second, China used the COVID pandemic to further construct a robust surveillance state and exercise dehumanizing control over its population. Russia didn’t go nearly as far as China, but it also used the opportunity to increase surveillance and control.

Third, many potential dissidents left Russia at the start of the Ukraine War.

[5]

[5]You can buy Greg Johnson’s The Year America Died here. [6]

And fourth, Russia as a historical empire has experience in dealing with its subject peoples that the US lacks. Russia was able to convert the Chechens from sworn enemies into shock troops in a little over a decade. In contrast, the US State Department excels at alienating peoples. The US itself is certainly at risk of splintering after the events of 2020, as outlined in Greg Johnson’s The Year America Died [7]. Russia and China are not.

This brings us to the single most important aspect of The Next 100 Years: its widespread popularity, especially among establishment policymakers and those who implement them. This could explain many of the regime’s odd decisions. For example, the establishment’s handling of the Ukraine War seems less about benefiting Ukraine than destabilizing Russia by drawing out the war at Ukraine’s expense in blood and ours in gold. This might make sense when viewed from the perspective of Friedman’s rational, yet incorrect predictions. Friedman’s claim that “Russia will most likely splinter” became “Russia will definitely splinter,” and then to “We must break Russia up to fulfill the prophecy of an American century!”

Friedman’s incorrect predictions about Russia and China threw off the rest of the predictions as well. His prophecy of a future Japanese-Turkish coalition that would fight a sci-fi-style war against the US is as intriguing as it is unlikely.

One of Friedman’s predictions that is likely to come true is that Poland and its neighbors in the Visegrád Group will become regional powers. This will indeed happen because they have no other choice. Russia is their enemy, while the US and Western Europe have become unreliable as a result of their decline. Friedman’s fundamental premise is therefore entirely correct in this instance: nations and leaders do have a kind of destiny, because their choices are constrained. History has thrust greatness upon Eastern Europe, and I wish them luck in rising to the task.

Friedman hits the mark more accurately when it comes to technological matters. I don’t know if we will see warriors fighting in armor powered by electricity beamed from space, but Elon Musk’s recent Space X endeavors are certainly turning the dream of energy transmitted from space into a reality.

Friedman also provides a much-needed sanity check on the Left’s climate hysteria. He predicts that global warming will not become an issue due to space-based energy and falling birth rates, which together will resolve the issue on their own. To this I would add that climate change is powered by the Sun more than anything else, and that a small amount of global warming could actually be beneficial for agriculture, such as it was during the medieval warming period.

Despite my criticisms, I strongly recommend The Next 100 Years because it is a fast and engaging read and a rare opportunity to meaningfully engage with an alternate viewpoint. Even Friedman’s errors are reasonable, and we can supplement his method with our facts. And while I have not yet read it, from the description of Friedman’s 2020 book, The Storm Before the Calm, it appears that Friedman is standing by his prediction that the US will ultimately prevail.

Friedman says that he is fine with being wrong, however, which gives him the courage to apply his method and sometimes make correct predictions. This is a refreshing change from the endless pursuit for hot takes that we see in both the dissident Right and the mainstream media.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

Due to an ongoing cyber attack [8] from those who disagree with our political discourse, our Green Money echeck services are temporarily down. We are working to get it restored as soon as possible. In the meantime, we welcome your orders and gifts via:

- Entropy: click here [9] and select “send paid chat” (please add 15% to cover credit card processing fees)

- Check, Cash, or Money Order to Counter-Currents Publishing, PO Box 22638, San Francisco, CA 94122

- Contact [email protected] [10] for bank transfer information

Thank you for your support!

For other ways to donate, click here [11].