Céline’s Guerre

Posted By Margot Metroland On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,741 words

The following is part of Counter-Currents’ commemoration of Céline’s 129th birthday on May 27.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Ed. by Pascal Fouché

Foreword by François Gibault

Guerre

Paris: Editions Gallimard, 2022

I must have been lying there for much of the next night. The whole ear on the left was glued to the ground with blood, the mouth too. Between the two there was an immense noise. I fell asleep in this noise and then it rained a heavy rain.

I’m not quite sure how that works, your ear and mouth both glued to the ground with dried blood. Maybe there’s a huge clot of blood? Anyway, this is how Louis-Ferdinand Céline, alias Destouches, begins his small novel Guerre, partly based on his experiences being wounded and hospitalized in 1914-15, during the Great War.

It was written in 1933-34 but published only last year. We can date the manuscript confidently because he wrote the Los Angeles address of his American girlfriend, Elizabeth Craig, on the back of one of the ms. pages (she’d recently moved back there from Paris), along with a draft of a letter to her. In the summer of 1934 he would go to California to look her up, and also to sell his bestselling novel Voyage au bout de la nuit (Journey to the End of the Night) to the movie studios. Neither effort quite panned out. Elizabeth had taken up with someone else, and Céline’s novel was thought too racy for the new Motion Picture Production Code.[1] [2]

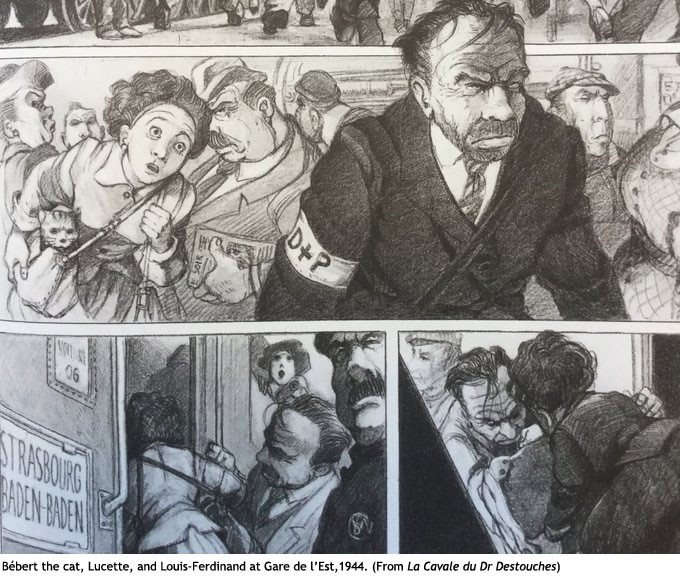

Guerre was one of three unpublished manuscripts that Céline left behind in a cupboard when he fled Paris in mid-1944, with his wife Lucette and their cat Bébert. What happened to the works afterwards is speculative and murky, but it appears they were lifted by a professional looter in 1944. They ended up in the hands of a Left-wing Libération journalist who pretty much sat on them for many years, not wishing Céline’s widow to benefit from their publication. Céline, after all, had been a renowned collabo, propagandiste, anti-Semite, etc., etc.

I regret to say that an English translation of Guerre is not yet available, but given this work’s brevity and uncomplicated prose, an English version should be available before long.

The French edition of Guerre and its sequel, Londres, were both published last year by Gallimard. The third manuscript, a medieval saga called La Volonté du roi Krogold, remains unpublished at this time, but portions of it appear in Céline’s Mort à crédit (Death on the Installment Plan) and also in Guerre, as dreams or imaginings when the narrator is hospitalized. Céline therefore had special affection for this Krogold work, as one would for a gifted but autistic child. His publisher, Denoël, refused the book around 1933, despite the spectacular success of Céline’s first novel, the aforementioned Voyage au bout de la nuit.[2] [4]

Getting back to the opening of Guerre, the narrator is describing in detail his painful consciousness as he lies on the battleground, numb and partly deranged. With his bloody mouth and bloody ear (and broken arm, we find), he sleeps, wakes up in the rain, and looks at the remains of another soldier:

Over to the side there was Kersuzon, a heavy corpse all stretched out under the water. I waved an arm towards his body, and touched. The other arm I couldn’t feel. I didn’t know where the other arm was. Kersuzon had gone up in the air very high, whirled in space, and then came down to shoot me in the shoulder, right through the raw flesh.

The wounds are partly autobiographical, though the author was never wounded in the head. So says Céline’s literary executor, François Gibault, in the book’s Foreword. From a self-diagnostic report Céline supplied to his jailers during his time in Denmark, after the Second World War:

Permanent headache (or almost) (cephalgia) against which any medication is almost useless. I take eight pills of gardenal a day — plus two pills of aspirin . . . I have my head massaged every day, these massages are very painful to me. I suffer from cardiovascular and cephalic spasms which make all physical efforts impossible — (and defecation). Ear: Completely deaf left ear with uninterrupted intense ringing and whistling. This state has been mine since 1914 when I was first injured when I was thrown by a shell bursting against a tree.

“I caught the war in my head,” the narrator says early in the book. “It is shut up inside my head.” This is a running theme in Guerre: headaches, painful tinnitus. So is that perennial Céline leitmotif, disgust:

Deaths here and there. The guy with bagpipes, he had burst himself like a grenade, you might say, from the neck to the middle of the pants. In his very belly were already two cushy rats which covered his rucksack with stale crusts. It all smelled of rotten meat . . .

[5]

[5]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here [6].

Ferdinand — for such is his name, same as Ferdinand Bardamu in Voyage — now gets up and forages around, finds a couple bottles of burgundy and some canned monkey meat [slang: bully beef] that had exploded from the heat but is still edible. He runs into some British soldiers who take him to hospital. And that’s where we spend most of the book. We’re somewhere near Ypres, where Céline himself spent some time in hospital after being wounded in 1914.

Ferdinand’s parents journey up to see him; he thinks them sniveling, pathetic bores. He makes friends with another wounded soldier, a bed-neighbor named Bébert, after whom the author will eventually name his cat. Or maybe it’s the other way around; one of the loose ends in the draft manuscript is that the same character is often called Cascade. Cascade/Bébert has a pretty young wife, Angèle, who is a prostitute. Both come to unfortunate ends. At one point Angèle asks Ferdinand to work a scam with her, playing an angry, cuckolded husband who barges in while Angèle is servicing her British john, and then Ferdinand angrily leaves, while the “terrified” harlot weeps and shakes the soldier down for even more money.[3] [7]

Another charming lowlife character is the nurse, Mlle. L’Espinasse, who pleasures the wounded and dying men, and perhaps herself, with hand jobs and maybe more. There’s some intimacy with a corpse, the narrator tells us. Eventually Ferdinand blackmails her with these stories, enabling him to be transferred to a hospital in London. (That much is semi-autobiographical; Céline did go to London in 1915 after his hospital stay in Belgium, but he was fully recovered and put to work at the French Consulate.)

As is common with Céline, the narrative slips in and out of fantasies and hyperbolic riffs. Did nurse L’Espinasse actually have coitus with a corpse? Or is Céline just having us on, parodying the soldier-nurse romance in A Farewell to Arms? I find the latter thought irresistible. For four or five pages we have a reverie about King Krogold and crusading quests. Two British officers drive up, and their names are a delight: “Major B. K. K. Olisticle of Ireland and Lieutenant Percy O’Hairie, really a young woman of distinction and svelteness.” So that’s how British/Irish names look to the French? I see, very comical. What’s even funnier is trying to sort out what the author means by Lt. O’Hairie being an attractive young woman. Would a British Army Major have a female adjutant in 1915? I do not believe so. So perhaps Céline means Lt. O’Hairie looks like a young lady . . . or perhaps is one . . . inadequately disguised. This is Céline’s world; we have to make the best of it.

Alice Kaplan, writing last year in The New York Review of Books [8], blithely judged Guerre to be a 150-page outtake of Voyage au bout de la nuit. It’s actually about 130 pages in my standard-size, large-type Kindle edition. Thus a very short novel indeed; though there are lots of forewords and appendices and images of heavily reworked holograph pages, in ink and pencil. While it looks as though the manuscript was last reworked in early 1934, it could be a third-generation rewrite of something antedating Voyage. An outtake? Probably not.

Kaplan sniffily dismissed the little book as sloppy writing and acted appalled that a book by such a banal, evil man was getting so much attention:

With 150,000 copies in bookstores since its publication on May 5, Guerre may be the first Céline book read by a generation that lacks the background for understanding what’s at stake. It is serious.

Groan. Yes, we know: those who do not remember the past are condemned to write shaggy-dog tales about it, in the NYRB and elsewhere. But of course that’s Alice’s job, slamming Robert Brasillach and Louis-Ferdinand Céline, and French Rightists in general. And it’s been a steady living.[4] [9]

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [10].

Notes

[1] [11] The story of Céline, Hollywood, and Elizabeth Craig was covered here [12] in 2018.

[2] [13] From a French-language website [14] in 2012, some years before the missing manuscripts turned up: “If we want to look closely at Krogold’s theme, we must rely on the fragments we find in Mort à crédit. Although Céline speaks several times of a whole lost manuscript, an ‘epic novel’, a ‘Celtic legend’ entitled La Volonté du roi Krogold, we have found no trace of it. Fortunately, the legend, as it appears in Mort à crédit, is enough to reveal very interesting aspects of Céline’s fundamental vision and therefore provides us with a precious key to understanding his work.”

[3] [15] “Fake victimhood: a fine allegory of Céline’s own modus vivendi,” comments the disapproving Alice Kaplan in her New York Review of Books [8] piece.

[4] [16] Kaplan is sort of atypical. Jewish authors and critics are not all condemnatory of Céline. Elsewhere in that NYRB review she notes that Morris Dickstein commented that Death on the Installment Plan, “with only minimal adjustment, could sit on the shelf of Jewish American classics.” Philip Roth was also a fan. In fact, Dickstein has claimed Roth wrote Portnoy’s Complaint under the influence of a Ralph Manheim translation of Death on the Installment Plan, from which he drew not just the theme of masturbation but “the heightened farcical tone of the monologue, the sense of pain at the heart of laughter, which had little precedent in Roth’s work.” The quotations come from “Sea Change: Céline in America,” in Dickstein’s A Mirror in the Roadway: Literature and the Real World (Princeton University Press, 2005). Elsewhere in the minyan, we have Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker [17], who sees Roth channeling Céline in Sabbath’s Theater. Oy vey.