Remembering Emil Cioran

(April 8, 1911–June 20, 1995)

Anthony Bavaria

Though I am certainly no Emil Cioran scholar, I can write about him from the point of view of having been impacted by him. Would-be Cioran enthusiasts beware, for his influence is not necessarily a bright one; after all, his ideas belong to a school of thought known as philosophical pessimism. Though I am sure he would hate it, I am going to attempt to extract some positivity from his writings.

I am focused much more on the past than the future. What makes Cioran’s material absolutely vital is that it helps explain our history — in the most downtrodden, miserable way — and how the modern era came to be. Only after arming oneself with this knowledge and viewpoint can the man of thought properly shape his outlook on the future. It can be negative, as Cioran’s certainly was, but no less truthful — which, in my opinion, is a prerequisite to reality and sanity.

Though most of my reading comes from recommendations on Counter-Currents or elsewhere in the greater dissident sphere, I found Cioran completely by accident. Perusing the shelves of a used bookstore in 2017, the spine of a book with the interesting title A Short History of Decay caught my eye. After reading the foreword by Eugene Thacker, who admitted to discovering him in the same manner, and where he states that “perhaps the only way to encounter Cioran is to stumble across him, as if by accident or by fate,” I decided to give the book a try. It is an incredibly difficult read, but for me he can pack more meaning into a single sentence than almost anyone in the world of philosophy.

The very first page of the first chapter, under the subject Genealogy of Fanaticism, reads, “Even when he turns from religion, man remains subject to it; depleting himself to create fake gods, he then feverishly adopts them: his need for fiction, for mythology triumphs over evidence and absurdity alike.” I applied this passage to the world around me: the worship of black people, the denial of crime statistics, feminists venerating the flooding of their homelands by misogynistic cultures, Marvel movie masturbation, the war on Christian values — and it immediately aligned; furthermore, nothing about it seemed overtly pessimistic. It’s simply true.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s Graduate School with Heidegger here

But then I wondered, what can be done about it? On the next page Cioran adds, “Only the skeptics (or idlers or aesthetes) escape, because they propose nothing, because they — humanity’s true benefactors — undermine fanaticism’s purposes, analyze its frenzy.” Again, my hair was blown back. Though I would never recommend simply doing nothing to combat our crazed world, what Cioran hints at here is merely side-stepping from the crosshairs; not with a how-to list, but with a mindset.

The introduction to Chapter Three addresses the concept of decadence and prejudice in civilization. Cioran states:

Prejudice is an organic truth, false in itself but accumulated by generations and transmitted: we cannot rid ourselves of it with impunity. The nation that renounces it heedlessly will renounce itself until it has nothing left to give up.

From this alone, it is clear Cioran is one of our guys. Speaking of the mindset required to push forward mentioned above, he expands, “It is then up to the enlightened individual to flourish in the void — up to the intellectual vampire to slake his thirst on the vitiated blood of civilizations.”

Cioran’s style of writing has been described as nothing more than a series of aphorisms, none of which are very connected. The philosopher himself acknowledged this, referring to them as “momentary truths”; not unlike the tweets and memes we’re familiar with today. Cioran’s approach, without a doubt, is much more elegant. But the nihilism persists and is unrelenting. Guillaume Durocher for his part described Cioran’s writing at Counter-Currents thusly:

A patriotic, health-conscious régime would be well within its rights in banning Cioran’s voluminous works from the bookshops as the corrosive scribblings of an insomniacal bipolar bookworm, though he could perhaps be tolerated in academic specialists’ libraries and underground samizdat, where any damage would be limited.

A Short History of Decay goes on to address a plethora of topics: time, ennui, history, civilization, hate, culture, power, tolerance, knowledge — the list goes on. The more you read of his outlook on the world, the more his background begins to make sense. Born in 1911 in Transylvania, which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to a religious family of Romanian descent, it was clear from an early age that Emil was gifted. Learning was important to him, and he was awarded a scholarship to the University of Berlin in the early 1930s. For a young man studying Nietzsche, Spengler, Heidegger, and hob-knobbing with other Continental thinkers of the era, it is no surprise that he was an early supporter of German National Socialism and Italian Fascism, as well as his native country’s Iron Guard. Cioran’s intellectual stances on Western Europe’s Right-wing movements often chafed with Romania’s highly traditional outlook, however, to the point that he soon left for Paris and never returned home.

It is worth emphasizing that, at the time, Paris had yet to become the arbiter of a dead culture, and a mind like Cioran’s could still flourish there. Even to this day, Cioran and other French thinkers (though he was Romanian, Cioran lived in Paris and wrote in French for most of his life) sympathetic to fascism have, rather surprisingly, been let off rather lightly by today’s intellectual establishment. The 2012 reprint of Decay has a positive blurb taken from a Los Angeles Times review on its cover, meaning an L.A. Times writer actually reviewed a book by a “Nazi.” The same relative understanding is accorded to Louis-Ferdinand Céline, who arguably was much more supportive of the Germans leading up to and during the war; this, compared to the fate of someone like Ezra Pound, who did 13 years of prison time (albeit in a mental institution) for his pro-Fascist propaganda, is astonishing. (Listen to Michael Walker’s excellent lecture on Céline and other pro-Fascist French authors of the war years and their fates, “Four French Collaborationists: Châteaubriant, Céline, Drieu, Brasillach.”)

Though Emil Cioran would later renounce his early affinity for fascism, even going as far as removing sympathetic passages to it in revisions of his own work, it’s no wonder that a pessimist, given what transpired in Europe in the 1930s and ‘40s, would do this. In fact, I would go as far as suggesting that it was historical events and the fate of fascism which bolstered Cioran’s pessimism. And tellingly, A Short History of Decay, one of the most depressing and somewhat black-pilling books I’ve ever read, was published in 1949. He then went on to live the life of a typical Continental intellectual: reclusive, eccentric, unmarried, lazy — yet still principled.

To learn more about Cioran and to read excerpts from his works, see these other essays on Counter-Currents:

Cioran’s Political Writings:

- “Ode to the Captain” (on Corneliu Zelea Codreanu)

- “Aspects of the German Soul”

- “Letter from the Third Reich”

- “Hitler in the German Consciousness”

- “Italy, Mussolini, & Fascism”

- “The Greatness & Decay of France” (from De la France)

- “Cioran on Civilization and Decadence” (from De la France)

- “Cioran on Decline” (from De l’inconvénient d’être né)

Cioran’s Philosophical Writings:

- “Morbid Meditations” (from Précis de décomposition)

- “The ‘Celestial Dog’”

- “Travails of a Metic”

- “Unconscious Dogmas”

- “The Motivational Cioran” (from De l’inconvénient d’être né)

On Cioran:

- Guillaume Durocher, “Between Buddha & Führer: The Young Cioran on Germany” (Czech version here)

- Guillaume Durocher, “Cioran’s On France: Thriving Amidst Decay”

- Christopher Nason, “An Infamous Past”

- James J. O’Meara, “A Personal History of Moral Decay”

- Alain Soral, “Cioran: Aesthete of Despair”

- Gina Puică and Vincent Piednoir, “Cioran, Germany, & Hitler”

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Remembering%20Emil%20Cioran%0A%28April%208%2C%201911%E2%80%93June%2020%2C%201995%29%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Popcult Humor from Wilmot Robertson: Remembering Wilmot Robertson (April 16, 1915–July 8, 2005)

-

Remembering Dominique Venner (April 16, 1935–May 21, 2013)

-

Remembering Jonathan Bowden (April 12, 1962–March 29, 2012)

-

Remembering Emil Cioran (April 8, 1911–June 20, 1995)

-

The Man of the Twentieth Century: Remembering Ernst Jünger (March 29, 1895–February 17, 1998)

-

The Power of Myth: Remembering Joseph Campbell (March 26, 1904–October 30, 1987)

-

Remembering Flannery O’Connor (March 25, 1925–August 4, 1964)

-

Remembering Kriss Donald (July 2, 1988–March 15, 2004)

15 comments

To Tucker Carlson,

Taking one’s own side is NOT a Nazi idea, Tucker, taking your own side is how Nature works, & has been this way ever sense life began. Taking our own side is natural & normal & how we protect our children. Tucker, you are intentionally attempting to discourage us Europeans from coming together, from collectivizing. You, Tucker, are a traitor.

——————————————————-

Suggest all of us to collectivize. It won’t hurt to let Tucker know that we are onto him, that we know what he is doing, which of course, means he is throwing his children under the bus, fore, it does not matter how rich he is – his minority children will not escape reality.

After reading this site a bit, I no longer consider myself a nazi, but I still consider it a great honor to be called a nazi. It’s truly great honor to be compared to my great-grandfathers from Wehrmacht, to Horst Wessel, Herbert Norkus, Alfred Rosenberg, Julius Streicher, William Joyce, Rudolf Hess, Hans Ulrich Rudel, Leon Degrelle, George Lincoln Rockwell, William Pierce, and so many other glorious heroes of our race! So don’t be angry next time when someone calls you a nazi, and instead consider that a great honor!

Wow thanks, ordered the book. And for the links to the video. That’s what I think too, that most ideologies are substitutes for religion in our lives. Chesterton said something like this in defense of Christianity. The biopsychosocial impulse to religion is innate, so it’s best to fill it with something minimally harmful and most salutatory for the group. One group has solved this problem really well.

I’m reading Ask the Dust right now. I have some of my bizarre insights to share about it, but I’ll save it until I’m finished, if anyone wants to hear. Basically, it’s about Pound and JK Toole, is what I’m suspecting.

“most ideologies are substitutes for religion in our lives”

Though its always been this way, it seems to be more true than ever in our current time.

Glad to hear you’re reading Ask the Dust as well, interested to hear your opinion when you’re done with hit!

I finished Ask the Dust. It was pretty good. There was something infectious in his writing style that pulled me along. I think I most liked the portrait of an early twentieth century LA, and the characterization. As to the plot, I’m not sure. I suppose it’s mainly autobiographical with a dash of the IT thrown over it heavily. Would a young Girl really fall desperately in love with an old, invalid man like that? Does that mean there’s hope for ME, lol?! Thanks for telling us about this book.

Other great LA movie: Collateral.

Yea the plot is honestly nothing mesmerizing, but like you said, Fante’s “infectious… writing style” and “portrait of an early twentieth century LA, and the characterization” are exactly what do it for me as well.

And yea Collateral is great, though nothing trumps Heat for me in that vein of movie.

Now, I didn’t like Heat. Unrealistic. Your work is the single biggest factor in my renewing my counter currents subscription, I want you to know!

I just saw Tar, and I liked it too. I actually thought it was documentary up until the part where they were suing, and I was like “…wait, she would be liable for that?” And then I realized. Why does she vommit in the scene at the Thai brothel? I didn’t get that.

Another qualified but positive take on Cioran in this excellent introductory overview.

I started to see Cioran as a self-help guru after listening to and rereading the transcript from this linked podcast.

Cioran also had positive things to say about the value of suffering and failure that are of use in the current situation. Funny how he could find meaning even in these. It’s an entirely appropriate subject to talk about on Good Friday afternoon.

Personally, I now think it is absurd for we mere mortals to think there is no higher purpose and meaning to life. How would we know at our level?

I remember being gobsmacked at 21?when someone said, “Life’s a bitch, and then you die.” It deeply affected me. Cioran could have helped back then. It could be sold as the joys of pessimism.

Now I understand this:

“Only optimists commit suicide, optimists who no longer succeed at being optimists. The others, having no reason to live, why would they have any to die?”

—E.C.

https://www.philosophizethis.org/transcript/episode-156-transcript

“Only optimists commit suicide, optimists who no longer succeed at being optimists. The others, having no reason to live, why would they have any to die?”

It’s quips like this that allow me to take an interest in the pessimists. A) it rings true and B) I’ve seen this in my own personal life. People with the most ‘going for themselves’ always seem to be the ones offing themselves, as opposed to human waste, who seem to cling to life more than anyone.

Thanks for this, Anthony. I have a similar take on Schopenhauer’s pessimism. The idea of an ethics of “overcoming the will to live” seems pretty depressing. But another way of describing the will to live is the fear of death. Overcoming the fear of death, however, is profoundly liberating, because such fears hold us back from self-actualization. This also made sense of Schopenhauer’s large compendium of practical advice on living well. Once one has lost the fear of death, one is really able to plunge into life.

Thanks Greg!

“Schopenhauer’s large compendium of practical advice on living well”

Its pretty easy to write off a pessimist, but if they’re operating at the cognitive level of Cioran or Schopenhauer, there is certainly something to be gained from from their views.

Do you know of any first-hand accounts written by anyone about what it was like to be around either of these two?

Check Searching for Cioran Ilinca Zarifopol-Johnston

From the book:

At a table next to Sartre, who confidently draws on his pipe, sits a quiet young man, chain-smoking cheap Gauloises. Modestly but correctly dressed with coat and tie, his fedora hat carefully placed on top of a heavy navy overcoat folded next to him on the red velvet bench, there is a vaguely foreign, un-French air about this man, something formal and old-fashioned which strikes an odd note in the bohemian atmosphere of the café. He has a remarkable face: a head of light-colored hair like a lion’s mane, brushed backward, piercing green eyes under a permanently frowning brow and a pinched, willful mouth set in a square jaw which he pushes forward in a moue of great determination. He comes every day, from eight to twelve in the morning, two to eight in the afternoon, and nine to eleven at night. “Like a clerk.”1 He smokes and listens to the heated arguments at the next table. He always sits next to Sartre but never says a word to him. Simone de Beauvoir is also there. Whenever she takes out a cigarette, the young man stands up, bends towards her ceremoniously, and, still silent, lights it for her. She thanks him with a nod of her head; he nods back respectfully and sits down. Every day that winter the silent ceremony is repeated. No one ever asks who the foreign-looking young man is. Every day, he sits without a word next to the “idol” of the French cultural scene. Is he never “tempted” to speak to the idol?2

The young man’s name is Emil Cioran. At the time we see him eavesdropping on Sartre and his group, he is a Romanian doctoral student, in Paris on a renewable fellowship since 1937. But he hasn’t yet written a single line of his thesis. He never will, in fact. He is not really a student; he is a writer. Nor is he as young as he seems: though thirty-three is not old for a doctoral student, some of Cioran’s apparent youth is a feature of his foreignness, which he will cultivate as a permanent aspect of his persona.

He is not even a French writer, yet. His equivocal position on the margins of Sartre’s group, gravitating around the axis of French intellectual authority, always silent but always present, sums up this ambitious and divided young man, in quest of a center that will focus his own creative energy. In Romania, he is well known, the published and controversial author of five books and numerous articles. In Paris, in 1943–44, he is nobody, just an exile from Eastern Europe, hoping to make a name for himself in the City of Light. He is finishing a book about Nazi-occupied Paris as symbol of the final decay of Western civilization. But the book, written in Romanian, will remain, forgotten or abandoned, in manuscript form until its publication in 1991. For the young Romanian suddenly decides, the very next summer, to abandon his native language and to write henceforth in French, at last to break into, as it were, the conversations of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. (…)

In retrospect, young Cioran’s silent position next to Sartre at the Flore was not at all accidental. Cioran chose it deliberately. He watched and waited like a spy, quietly measuring his forces against Sartre’s to find out his own worth. “My path was the reverse of Sartre’s,” he said later, even though his essay on Sartre in the Précis, “On an Entrepreneur of Ideas,” shows how much Sartre’s model was on his mind.7 He could speak as well as Sartre, he had read much more, he would write as well as they—Sartre’s circle—were writing. His silence was not shyness or intimidation, but inordinate pride. With his body strategically placed on the margins of fame, Cioran made a statement. He was nearly inside the magic circle of Sartre and French cultural life, which had enormous prestige in the eyes of European intellectuals, especially marginal Europeans like Romanians. Just outside the circle, or rather on its border-line, the ambitious interloper worked silently and tenaciously in isolation for another five long years—scribbling away like Dostoevsky’s underground man, in the cheapest hotel rooms in the Latin Quarter—to gain the place at the table he had marked out for himself, next to Sartre, publicly recognized in France. But unlike Dostoevsky’s underground man, whose “revenges” were never more than pathetic failures to impress imaginary opponents, Cioran’s “revenge” was a blazing success. Hailed by Nadeau as a “twilight thinker,” by André Maurois as the new “moralist or immoralist,”8 by Claude Mauriac for “masterly language . . . closer to Pascal than Vigny,”9 the Romanian-born Cioran had not merely arrived on the French literary scene; he blazed across it like the meteor, symbol of obscurely powerful poetic genius, in Mallarmé’s poem, “calme bloc icibas chu d’un desastre obscur”10 [calm [granite] block fallen down here from some dark disaster].

This is the story my book has to tell: how an unknown young man from the margins of Europe, with a fanatic will to transform himself, achieved fame “in a country where prestige is everything.” Tnis biography covers the crucial first stages of his career, from 1911, the year of his birth, to 1949, the year of his consecration as a French writer, which marks his final break with his Romanian roots.

But the best information about Cioran you can find in Notebooks and interviews with Cioran, unfortunately neither were published in English (seperate interviews are available).

***

Cioran on Susan Soca:

She Was Not of Their World . . .

I ONLY MET HER TWICE. Seldom enough. But the extraordinary is not to be measured in terms of time. I was instantly conquered by her air of absence and bewilderment, her whisperings (she didn’t speak), her uncertain gestures, her glances that did not adhere to people or things, her quality of being an adorable specter. . . . “Who are you? Where do you come from?” were the questions you wanted to ask her right away. She wouldn’t have been able to answer, so identified was she with her mystery, so reluctant to betray it. No one will ever know how she managed to breathe — by what aberration she yielded to the claims of breath — nor what she was seeking among us. The one sure thing is that she was not from here, and that if she shared our fallen state it was merely out of politeness or some morbid curiosity. Only angels and incurables inspire a sentiment analogous to the one you felt in her presence. Fascination, supernatural malaise!

The first moment I saw her, I fell in love with her timidity, a unique, unforgettable timidity that gave her the appearance of a vestal exhausted in the service of a secret god, or else of a mystic ravaged by the nostalgia or the abuse of ecstasy, forever unfit to reinstate the surfaces of life!

Overwhelmed by possessions, fortunate according to the worlds she nonetheless seemed utterly destitute, on the threshold of an ideal beggary, doomed to murmur her poverty at the heart of the Imperceptible. Moreover, what could she own and utter, when silence stood for her soul and perplexity for the universe? And did she not suggest those creatures of lunar light that Rozanov speaks of? The more you thought about her, the less you were inclined to regard her according to the tastes and views of time. An unreal kind of malediction weighed upon her. Fortunately, her charm itself was inscribed within the past. She should have been born elsewhere, and in another age, in the mist and desolation of the moors around Haworth, beside the Brontë sisters. . . .

Knowing anything about faces, you could readily see in hers that she was not doomed to endure, that she would be spared the nightmare of the years. Alive, she seemed so little the accomplice of life that you could not look at her without thinking you would never see her again. Adieu was the sign and the law of her nature, the flash of her predestination, the mark of her passage on earth; hence she bore it like a nimbus, not by indiscretion, but by solidarity with the invisible.

Jesus, both of those passages were outstanding. Thanks for that… C-C community always with the endless recommendations, I can never keep up!

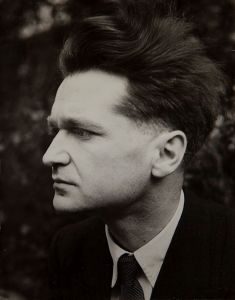

In his photo he looks like eraserhead

Lol absolutely. Pound had a similar haircut in his younger years… something about these right-leaning thinkers of yesteryear perhaps? Regardless, I love.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment