British Sculpture, Part II

Posted By Jonathan Bowden On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledPart 2 of 2 (Part 1 here [2])

Monument to George N. Hardinge (1781–1808), 1808 [3]

Here we have another Classical piece[1] [4] from St. Paul’s. Very sort of neo-Classical in feel. Idealized. A strong element of narratives creeping into sculpture at this time. This is from 1808, right at the beginning of the nineteenth century. It celebrates probably the death of a man in combat, maybe in the Napoleonic and French Revolutionary wars of the period. An angel has come down and weeps upon his tomb. A shroud has sort of been put on one side. The man, or the sort of transubstantiation of his corpse reanimated in accordance with the Christian doctrine of second birth, looks out into the distance. You see strongly elitist, hierarchical, and storytelling concerns three-dimensionally in stone in one of our major cathedrals.

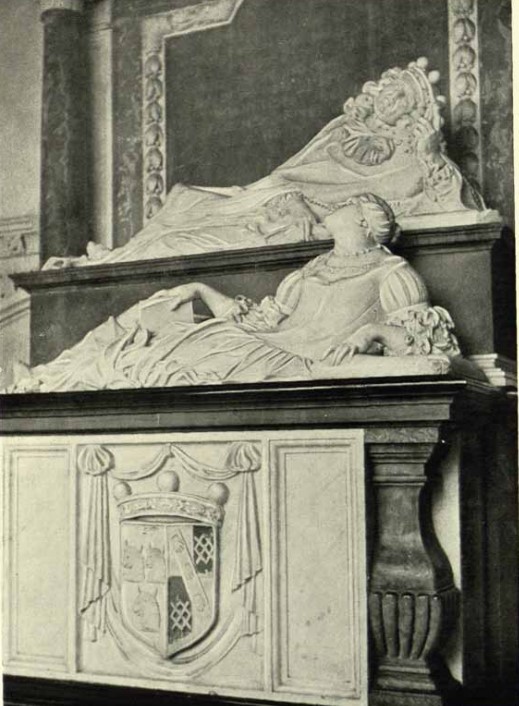

Here we have another piece[2] [6] which is almost a lying in state, really, but it’s of another aristocratic female lying side on, probably in a priory or vicarage in Kent. It’s again this desire to depict people in death in terms of Classical and Christian relief. There’s a certain heaviness to the piece. It’s very English, very stolid. There’s always been the view, particularly on the continent and by certain art critics, that English Classicism doesn’t work too well, because their comparison is always the Southern European tradition, when in actual fact it’s the same type of art, but it is a different version of it. It’s one in which some of the four-square and stolid values of English self-determination and three-dimensionality come through. From the very beginning of the sculpture that we’ve looked at in this short film, we can see certain abiding characteristics that pre-exist everything irrespective of style, time, and place.

Tomb of James Douglas (1662–1711), 1713 [7]

Here’s the Duke of Queensberry[3] [8] from earlier in the period that we’re looking at in terms of this particular type of Classical sculpture. Sort of Restoration 1660 through to the middle and latter stages of the nineteenth century, when the style doesn’t change too much and is very much of a piece. This is by John van Nost. It’s in Scotland. It’s very ornate, and it’s quite Baroque in spirit. He lies in death upon a bed or a divan, sort of swooning and thinking great thoughts with several cherubs above him, and there’s a plaque that lists his honorific titles and so on. There’s a sort of Doric column next to him and an arch over. Don’t forget this is life-size, extremely heavy, and the point is to indicate breeding, monumentalism, importance, and a link to the ancient world.

Sir John Cutler (1607-1693 [9])

Here we have another classicizing piece, life-sized, from about 1685. So, quite a way back, but the style you’ll notice from the Restoration in 1663 through to possibly the Great Reform Act in 1867 is very much of a piece. You could almost argue that this particular relief could have been done — this particular relief done of somebody I think was called Sir John Cutler[4] [10] — at any time during that period.

The Admiral Richard Tyrell Monument, 1770 [11]

This is a very large and ornate piece by Nicholas Read in Westminster Abbey, 1766,[5] [12] again in a style we’ve become conversant with during this phase of the film and this historical period with which it deals. It’s a monument to Admiral Tyrrell.[6] [13] Behind him in relief, you can see his ship. You can see battle scenes. You can see a sort of angel, or his guardian angel, or the spirit of victory, or his soul leaving his body in accordance with the doctrine of transubstantiation. You can see billowing sails overmastering the top of this angelic image and so on. It’s a very big relief with three-dimensional elements. Probably would have taken several years to actually carve and produce.

Here is a piece from the early part of the nineteenth century, 1825. The Bowler, from The Cricketer and The Bowler, from Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire by Henry Rossi. It’s a somewhat more populist work, this one, dealing with sport. The bowler, of course, is anonymous. It’s Classical in its deportment and delineation, but of course he’s clothed. And you see an encroachment of popular sensibility here, as well as a narrative element. It relates, of course, much more to the period in which it was produced than to notions about the ancient world. So, you’re beginning to see a sort of realism in certain elements even of Classical sculpture.

Tomb of Richard Ladbroke, 1730 [15]

Here we see another large mausoleum. It’s by Joseph Rose the Elder to commemorate an aristocratic[7] [16] or very upper-class family. It’s in Reigate in Surrey. Dates from the early part of the eighteenth century. The figures are relatively small, or maybe the photograph is from a distance. They may be life-size, but an enormous, monumental edifice here. It’s virtually like a sort of rock wall in neo-Classical and heightened vogue dedicated to the power and magnificence of this provincial family, and it shows you the desire these people have to immortalize themselves as provincial imperial figures in their area to be watched by their own community, as they perceived it, forever and ever.

Here’s another of these increasingly Rococo pieces that we’ve been looking at.[8] [18] A sort of heightened Baroque Classicism of an aristocratic couple gazing in an adoring way at each other, the female lying beneath the male. This is from Suffolk. The sculptor is Abraham Story. Again, we’re looking at the early part of this period, the Restoration through to the middle of the nineteenth century. This piece dates from 1678, and it shows, yet again, the ideals about themselves that the provincial English and British aristocracy had: a monumentalism, a heightened Baroque sensibility, a Classicism, and a desire to glorify in family, nationality, and self.

Field Marshal Earl Harcourt (1743–1830), 1832 [19]

Yes, here we have another rather Classical, not particularly Baroque, piece[9] [20]. Quite heavy, solemn. A peer of the realm, a sort of imperial ermine. Again, this desire to present oneself as a Victorian gentleman, as a man of leisure, as a man of means, also as a leader, as a statesman, and something of a Roman Senator in modernity. Again, this sculpture will be full size and will be there doubtless on a tomb or mausoleum to be admired by kith and kin in Oxfordshire.

Sir Francis Page (1661–1741), 1730 [21]

Here we have another slightly ornate piece, again a tomb: two life-sized vehicles, aristocratic husband and wife. Bewigged, in his case. Staring into the distance. Quite opulent. There’s a slightly Baroque touch to it. There’s a column that looks vaguely Doric to one side of them, and an arch. Again, it’s designed in a provincial setting. This is doubtless in a probably quite small church in Oxfordshire.[10] [22] It’s designed to indicate power, local resource, and that one is part of a higher civilization that’s solid, stolid, representational, and knows where it’s going and what it represents.

Right here we have another piece from Yorkshire,[11] [24] Reverend Thomas Whitaker. Possibly a local, sort of near-the-edge Anglican to non-conformist firebrand or Evangelical preacher of the time. Stares out serenely, but with a slightly Puritanical face at his would-be congregationists. Again, you see even extended out to probably a member of the gentry who happens to be in the clergy the same classicizing and heroic tendencies. A virtual full-size replication of self, continuation of one’s bodily existence in stone after death, power, and permanence. A civilization that really was encyclopedic and thought that they could define everything, determine everything, knew what was what, and had the future in their hands.

Robert Southey Memorial, 1843 [25]

[26]

[26]You can buy Jonathan Bowden’s Reactionary Modernism here [27].

Here we have a slightly new type of sculpture,[12] [28] not in its form or delineation. Still Classical, but you notice there’s a Romantic feel coming in. It’s quite naturalistic and realist, up to a point, given the classicizing tendency we’ve already mentioned. It’s also biographical. It’s actually of a person: Southey the poet.[13] [29] It also relates to a new movement and a new sensibility in the arts, what will become the dominant tendency of the whole of the nineteenth century, and this is the Romantic movement. You notice he’s not wearing a wig. He stares directly at the sculptor’s eye, if you like. Although it’s in Westminster Abbey and it dates from the 1840s, Southey, a slightly forgotten early Romantic poet now who wrote a famous biography of the naval hero Nelson, looks out at you and is the dawn of a new sensibility: more representational, less idealized, and in their own minds, a return to natural forms.

Rear Admiral Charles Holmes (1711–1761), 1761 [30]

Here we have another heroic and classicizing piece[14] [31] of a military figure, but he’s also partly dressed in the military uniform of a Roman commander from the ancient world, even though he’s got a cannon behind him and a coat of arms above. So, you’ve got this idea of modernity, cannon fire from the middle of the 1700s, and yet at the same time a Roman imperial statesman who in death looks out at the future and the past.

The Last Judgement & Memorial to John and Elizabeth Ivie [32]

Here’s an interesting relief,[15] [33] even though the skulls are slightly three-dimensional, from Exeter in the West Country, St. Petrock’s Church, 1717, by a profound provincial sculptor called John Weston. It’s of Jonathan and Elizabeth Ivie, and you notice that the background relief which is above the figures and is sort of transfigured or transubstantiated souls, some of them bewinged like angels, very much relates to artistic works that could be done by Donatello or Bellini. With the skulls you have a Gothic touch, even though this is very much prior to the Romantic movement. You have in this art, deep down, a form of tomb art, really, an obsession with death and with decay, but also with finality. Don’t forget this was a world in which the next life was very close, was believed to be totally real, and the Christian way was to prepare for it. Therefore, the celebration of death in a manner which contemporary people would find very, very difficult to either stomach or understand was ever-present. To put your skulls on the side of a tomb to celebrate your life would have been regarded as normalcy for a high bourgeois family from the provinces like this at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Monument to James & Jane Dutton, 1791 [34]

This is a famous piece[16] [35] dating from the middle of the eighteenth century by Richard Westmacott the Elder. It’s in Gloucestershire. The upper part of this powerful sculpture consists of a guardian angel seen in feminine form raising the top of a lid of a burial urn and sort of mausoleum. She looks down in a beneficent way upon the corpse who will now rise to ascension.

From the same image, we see the object upon which the female guardian, angel, or spirit looks from above to below. This is the skeleton of the departed, who is now released from the burial urn and is looking up as a sort of fleshless monster at the angel who is freeing him from death. He’s about to rise in accordance with the high Christian doctrine of the Second Coming and the resurrection of the body and the Second and Final Judgment when, according to this particular theology, all will be redeemed or cursed and thrown down into darkness and Hell, and those who will not will ascend into Heaven and will in certain circumstances achieve again their own corporeal nature. So, you’ll be reborn in life in death, even with flesh, but the bones survive and are being raised by this angel. There’s a strongly Gothic element to this piece, but again, you see the obsessionality with death and with the overcoming of death seen in terms of Classical sculpture.

William Shakespeare, 1740 [36]

Here with a high Classical image from the 1740s by Scheemakers.[17] [37] It’s Shakespeare; you can see the beginning of the cult of the artistic personality in this work. You can see also the beginning of an almost cultic reverence for Shakespeare as a writer, which reaches a status of a secular god almost, in modernity, particular in anglophone culture. Occasionally regarded as rough and unhewn and Elizabethan and rather barbaric, Shakespeare comes in over stages and is gradually accepted despite certain Augustine and Victorian moral qualms with some of the plays or their style. Shakespeare is depicted as a heroic creator gazing upon the Muses, and this is the beginning of a Classical cultivation of artistic biography that will reach an apogee with endless versions of Beethoven’s face and upper body and torso and bust and so on in the nineteenth century atop almost every Victorian mantlepiece or piano. But this importance of the individual creative personality depicted physically becomes more and more apparent. Don’t forget we’re emerging from a period where priests, where warriors, where kings and queens were put into this form. Now the artist himself becomes the subject of his work.

The Death of Germanicus [38], 1774 [38]

Here we have another piece of a military character, drawn from Classical myth and history, the death of Germanicus by Thomas Banks from the 1770s. The naked corpse; warriors swoon around it, some of them peripheral figures, are almost in relief, their three-dimensionality is tapered and is moving back into the stonework — but the key central characters (two of which are youths or small children) are depicted almost three-dimensionally. The background characters, again, merge more into the stonework, so you’ve got this sort of relief tending to radical representationality. It is an attempt in high eighteenth-century formulation, to recap what they believed the sculpture of the ancient world to have been like and how it comes down to us both from Classical Greek sculptors like Praxiteles, but also from Hellenistic sculpture, dug up again, and made to bear witness in the imperial papacies of the higher Renaissance.

Here we have an extraordinary and interesting piece, which almost goes outside sculpture and then steps back into it again. This is of the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham, a key founder of modern liberalism as it’s come to be seen and practiced. He wears a sort of Quakerish hat, and this is his corpse. This is an example of corpse art, almost the first in the West. It’s called an auto-icon, and he believed that everyone should have themselves exhibited as a corpse, and as a sort of artwork/sculpture after death. This extant form is still around. You can still see it in the precincts of University College London and Senate House in Bloomsbury, if you notice his sort of decapitated head/facial mask, or one version of it, is between his feet. Increasingly, this sculpture is in very great disrepair. The head is believed to be full of maggoty blood and this sort of thing, because the non-cryogenic processes by which it was embalmed and created and frozen in time from the 1830s to today in the twenty-first century has gradually destroyed it. However, although this appears to many sensibilities to be ghoulish and freakish, this is part of a long Western tradition in its way. The death mask, the birth mask, the mask that’s taken from your face in adulthood — this was done for Keats, it was done for Beethoven, it was done for Cromwell, it was done for Napoleon, it was done for Wellington, it was done for all sorts of figures, and was regarded as quite normal.

Also, art and anatomy have always gone together, since the ancient world, and many artists see themselves [as] closer to surgeons in their coolness, coldness, and objectivity than they do to necessarily emotionally-based artists. It’s often a misconception of people who are never involved in the arts to think it’s all about emotion and not about reason. Bearing in mind that Western art is based upon the body, the cult of the body, and of the body’s decay in and towards death, is inevitably part of this. In anatomy, the tradition from Galen through Versalius and now through in the twentieth century to controversial practitioners of a sort of hybrid of the arts and the sciences such the German embalmer and contemporary anatomist Professor Gunther von Hagens are all part of this tradition that Bentham opened up with this piece.

What Bentham is really saying is: Here is my corpse, let my face and head be cut off and be used as something for people to look at, let my eyes be cut out and used as marbles by the children of tomorrow. It’s a totally materialistic attitude towards death that believes there is nothing after. One is reminded of Danton the French revolutionary who went on the scaffold, turned to the executioner, and said, “Show my head to the people. It’s worth looking at.”

Apsley Gate (Grand Entrance to Hyde Park), erected 1826-29 [40]

Here we have again a very Grecian model, it’s by Henning,[18] [41] it’s from 1828, it’s of Hyde Park Corner. Of course, millions of tourists and native inhabitants will have passed this, sometimes without seeing it at all day-on-day in the center of London. It’s based upon the idea of the Parthenon and the Elgin marbles and what they meant when they were brought over from Greece, and it’s yet another part of the heroicizing tendencies of early nineteenth-century art — this idea that we were the new Greece and the new Rome combined, and that in a rather Christianized way we could nevertheless bring the solidity of the ancient world to the modern, particularly in relation to memorials that dealt with war and sacrifice.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892), 1857 [42]

Here we have a mid-nineteenth century bust and sculpture which depicts the artist as hero, for the very best artistic and yet heroic figure. It’s of the poet laureate Tennyson,[19] [43] best known to middle-twentieth-century audiences by his poem to celebrate the defeat, as it were, of the charge of the Light Brigade. He’s depicted in a biographical, a representational, and a rather realist or naturalistic manner, and not bewigged, well out of the eighteenth century. A studied and sort of low-key heroic ombit to the piece, and yet it’s the artist as hero who gazes out with a solemn and mature gaze. It’s how they believed, in the middle of the nineteenth century, the Classical world would have depicted by a significant writer like Dio Cassius or Pliney or Catullus.

Frieze of Parnassus, Albert Memorial (detail), completed 1872 [44]

Here in this sort of lineup, or column of figures[20] [45] seen from the side, is a depiction in slight relief, but nonetheless three-dimensionally, of a catalog or chronology of British sculptors — famous ones, anyway. This is from the Albert memorial by Armstead and Philip, and many of the people that we’ve looked at in terms of their works earlier in this film are depicted here. Of course there’s a certain element of artistic imagination and license going on, because how would the sculptors entirely have known of the physiology of their forebears or predecessors, artistically speaking. But nonetheless we begin with Nicholas Stone, who we looked at several centuries before in this chronology. Bird is there; John Bushnel, whose eccentricities we mentioned at one moment is also depicted; along with Bernini and various people from the continent who infused the solidity of the English style with a certain Renaissance lightness of touch.

The Sluggard [46]by Frederic Lord Leighton, 1886 [46]

[47]

[47]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s More Artists of the Right here. [48]

Now moving from the middle of the Victorian period toward its end, the Romantic movement has certainly infused sculpture. It took a long time. Painting would be far more likely to succumb to Romantic treatment, in terms of Constable’s[21] [49] “we’re looking at nature,” Turner’s[22] [50] in pre-Impressionism, or the sort of Salvatore Rosa view of nature seen in a gothic or troubled manner. Three-dimensionally it would be more difficult to bring in the Romantic idea — but here it is, in Lord Leighton’s[23] [51] sculpture. Now, one thing that you notice is because the idealizing tendencies of Classicism are reduced, the sculpture is more naturalistic, and therefore the nude will obviously be depicted more sexually, or at least psycho-sexually. This caused, in the high Victorian period, of course quite a bit of consternation. But, if you like, the nude is becoming more real, and one has this paradox about Victorian culture that in its era, which is regarded by modernity as very repressive and judgmental, nevertheless its three-dimensional art is increasingly erotic in terms of the nature of the Classical tradition.

This tendency towards eros in stone can be seen even more in G. F. Watts’ Clytie,[24] [52] which is a sort of naked back of a servant girl looking over her shoulder. You possibly realize that, given the natural art element of this sculpture, it couldn’t be done from the front, because otherwise it would be regarded as straightforwardly pornographic. So, we’re now seeing the naturalization of the Classical urge as, of course, photography begins, and photography will affect all of the arts to the degree that Romanticism begins to come to an end towards the end of the nineteenth century, and by the turn of the twentieth century is virtually over and is replaced in modernity by the sensibility which is now called modernism. But the engine for this change — amongst many, many other complicated factors — is photography. In painting, it forces people not to reveal the nature around them, but to go inside the mind in relation to fantasy and dream and so forth as firstly still and then moving photography, namely cinema, the art of the twentieth century, takes over the realist and representational role in visual art. Similarly, in sculpture a turning away from the body and in towards a non-organic art of individual sensibility that doesn’t relate to the society, but purely the psychology of the artist, begins the trajectory which is called modernism. What we now see is a splitting away of the Classical dispensation. And radical regimes, fascist and Communist, are the only currents in the twentieth century where the monumental and classicizing tendencies of the last couple of centuries within the West are to be found. Even that is complicated and possibly should be the subject matter for another film.

So, this finishes off our relatively quick resume of English and British sculpture stretching over several thousand years. We’ve decided to end our film at the beginning of the twentieth century, end of the nineteenth, and I’ve ended it here because the modernist sensibility then takes over. Personally, I believe you need another film about modernist sculpture, even modernist art — another two films, maybe — because this sensibility is a total change and a revolutionary transformation in everything. So, the Classical tendency; the Christian, humanist, and post-Christian tendency; the pre-Christian tendency — two, three, four thousand years of work really comes to an end at the end of the nineteenth century. The representation of the physical body perfect and imperfect then goes into film, into still photography, into moving photography, and then into mass cinema film as well as elitist forms of artistic photography. Obviously, if you stop many classical films and freeze the frame, you actually have both a representational painting, but also at times a certain three-dimensionality to the piece rather like Mantegna’s Renaissance paintings, which were a combination of sculpture and painting.

Now, if we look at the English and British tradition, you have examples like Behnes’ bust of Queen Victoria, idealized from before her reign really begins. You have William Anderson’s version of the Scottish laureate or moral laureate [Robert] Burns from 1854. You have, as we depicted earlier in the film, the version of Robert Southey which exists in Bristol Cathedral and was completed by Bailey in 1845. And we have two famous sculptures which I would like to finish on, both for aesthetic and political reasons.

These are the images of Sir Henry Havelock from 1861[25] [54] and of General Sir Charles Napier in 1856.[26] [55] These were by sculptors such as George Adams. Now, both of these forms are very interesting, because Ken Livingstone, the present Mayor of London, when he was elected wanted to tear them down, or at least remove them from Trafalgar Square, where they sit at the front of the square, often ignored in comparison to Nelson’s Column, designed by Railton, with Bailey’s sculpture at the top and Landseer’s lions equidistant from the pillar. Now, many people, hundreds of thousands of people, will pass these sculptures of Havelock and Napier at the front of the square going down into Northumberland Avenue, where the Ministry of Defence now is, and they will not know who these figures are. These figures are imperialists from the Indian raj in the nineteenth century. One of them is responsible for putting down the Indian Mutiny with quite considerable bloodshed, and it’s because Leftists like Mayor Livingstone know this that he wanted these figures removed. He couldn’t get them removed, because his importance and alleged civic esteem as Mayor doesn’t extend to the appurtenances of Trafalgar Square. He’s got no control over the statuary in the square. He can ban people feeding the pigeons in the square, but he can’t remove sculpture. So, what he did to get his own back was he had the empty plinths at the far corner of the square, which is adjacent to the National Gallery behind it and looks across to the Canadian Embassy on the other side — he used that for Turner Prize exhibit art, deliberately to get back at the authorities who denied the fact that he could get rid of Napier and Havelock from the front of the square.

Charles James Napier, 1856 [56]

So, in this talk about aesthetics and politics we come full circle, because the high Victorian, Classical impulse exists in the central square right at the heart of our post-imperial city, London, where we now have a sort of anti-British and unpatriotic Mayor who wants to repudiate the imperial past — the imperial past which has in fact partly led, among other factors, to London’s multiracial present status. Nevertheless, the thing he wants to remove from the square is the symbolism of the past, is the way in which it classed itself, is its classification of itself — i.e., its Classicism.

So, to end this film, I would ask people when passing across the precincts of Trafalgar Square to have a look at these rather strong, slightly dour, stolid pieces of English sculpture at the front of the square depicting Havelock and Napier as imperial warriors and heroes in a subdued Classical manner, the images and reliefs and bulk masses that Livingstone wished to remove to some obscure place in Sheffield or Bolton, where you would never see them again.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [57].

Notes

[1] [58] Monument to George N. Hardinge [59] (1781–1808) by Charles Manning (c.1776–1812/1813) at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

[2] [60] Elizabeth Culpeper (or Colepeper, Lady of Leeds Castle) at rest in Hollingbourne Church, by Edward Marshall [61] (1598–1675). Unusually for the type, her hands are not clasped in prayer, but with one resting by her side and the other resting on her chest in repose. The Cheney Family’s heraldic beast, a theow or thoye, is shown at her feet. It was a strange, toothy animal with cloven hoofs and a cow’s tail.

[3] [62] Tomb of James Douglas [63], Second Duke of Queensberry (1662–1711), with his wife Mary, erected 1713. It is located in the Queensberry Aisle of the Durisdeer Parish Church [64], Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland.

[4] [65] This is not the exact statue of Sir John Cutler [66] to which Bowden refers, but another life-sized sculpture of him made by the same artist, Arnold Quellin (1653-1686) (Artus Quellinus). Cutler appears in similar pose and garb. This one is in Guildhall, London; the one to which Bowden refers is in Grocer’s Hall.

[67]

[67]You can buy Buttercup Dew’s My Nationalist Pony here [68]

[5] [69] Bowden incorrect states Tyrrell’s date of death as the date of the statue. The statue was unveiled in 1770, after Tyrrell’s death in 1766.

[6] [70] The Admiral Richard Tyrrell monument, Westminster Abbey, 1770.

[7] [71] The Richard Ladbroke monument [15] in St. Mary’s Church, Reigate, Surrey. The sculpture commemorates him and his family and was made between his death in 1730 and 1793. The reclining Ladbroke is between allegorical figures for truth and justice.

[8] [72] Monument to William, First Baron Crofts [73] (d. 1677) and his second wife, Elizabeth, Church of St. Nicholas, Little Saxham, Suffolk. [74]

[9] [75] Field Marshal William Harcourt [76], Third Earl Harcourt, sculpted by Robert William Siever. Two were produced and stand in St. Michael’s Parish Church in Stanton Harcourt, and in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle.

[10] [77] Memorial to Sir Francis Page [78] and his second wife by Henry Scheemakers in Steeple Aston church, Oxfordshire.

[11] [79] Vicar Thomas Whitaker [80] by Charles R. Smith, 1822, at the Parish Church of Saint Mary and All Saints [81], Whalley, Yorkshire

[12] [82] The Robert Southey Memorial in Westminster Abbey [25] by Henry Weekes, 1843, in “Poet’s Corner.”

[13] [83] Robert Southey, 1774-1843, an English poet of the Romantic school. He is the originator of the story of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears.”

[14] [84] Charles Holmes by Joseph Wilton [30], 1761, Westminster Abbey.

[15] [85] This funerary monument is at St. Petrock’s Church [32], Exeter, Devon. It was originally located at St. Kerrian’s.

[16] [86] This funerary monument to James Lenox Dutton and his second wife Jane shows a risqué angel with a slipped breast rather carefully trampling death underfoot. The Dutton couple only appear in relief on the burial urn lid that the Guardian Angel is holding. The monument is in St. Mary Magdalene’s Church, Sherborne, Gloucestershire.

[17] [87] Peter Scheemakers (1691-1781). This is in Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey, alongside the bust of Robert Southey also pictured. A reproduction of the Shakespeare memorial with altered text is in Leicester Square.

[18] [88] The frieze was undertaken by both John Henning the Elder (1771-1851) and John Henning the Younger (1801-1857). Although it is based upon the Elgin Marbles, it is not a direct replica. British art historian Dana Arnold comments that “the original intention was to create a scheme which was classical in essence, underlining the culture and sophistication of London and/or the monarch.” Rural Urbanism: London Landscapes in the Early Nineteenth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005). Original article at VictorianWeb [89].

[19] [90] Bust of Lord Tennyson [42] by Thomas Woolner (1825-1892) placed in Poet’s corner, Westminster Abbey, in 1895.

[20] [91] Specifically, the Frieze of Parnassus by Henry Hugh Armstead and John Birnie Philip, which chronicles historical and what were contemporary writers, poets, musicians, architects, and sculptors. The complete memorial is much vaster than the detail shown here.

[21] [92] John Constable (1776-1837).

[22] [93] William Turner (1775-1851).

[23] [94] Frederic Lord Leighton (1830-1896).

[24] [95] By George Frederic Watts (1817–1904), part of the Tate collection, ref. N01768.

[25] [96] Major General Sir Henry Havelock by William Behnes [97], 1861, which was erected and remains in Trafalgar Square, London.

[26] [98] General Sir Charles James Napier by George Gammon Adams [99], 1856, also resident in Trafalgar Square.