British Sculpture, Part I

Posted By Jonathan Bowden On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled6,261 words

Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here [2])

The following is a transcript of a video documentary by Jonathan Bowden that can be viewed on The Jonathan Bowden Archive here [3]. The transcription was made by V. S., with additions and notes by Buttercup Dew. Where public domain images of the works described by Bowden are unavailable, we have included links to offsite images of them.

Welcome to this brief film about English and British sculpture.

Let’s begin right at the beginning with something which can’t really entirely be described as a sculpture, but it’s Stonehenge, an enormous and a sort of semi-celestial monument the better part of 4,000 years old.

Grim, chthonian, profound, a pagan cathedral, freestanding. The Christianity of 2,000 years left it alone, and in a strange way the English and British monumental tradition in stone begins with this piece. There’s an extraordinary leap as well across the better part of four millennia to modernist sculpture which, Henry Moore-like, epitomizes the primitive and the fierce and the primeval and even the tribal.

So, let’s begin this analysis of what we have done three-dimensionally in the arts with the first cathedral that has come down to us on these islands from the ancient world.

Here we move on in time to a Celtic horse-mask[1] [5] from southern Scotland circa 200 BC or thereabouts, slightly dented now as it comes down to us, pre-Germanic in feel, ancient Celtic. The symbolism of snakes, almost, and swirls and that patterning that Celtic art so beloves. Obviously, it’s an item that comes from the battlefield and is essentially a piece of armor to protect a horse or to signify the power of a horse. In it we see something of pre-Germanic Britain, of a Britain that is yet to be influenced by Romans or people of Germanic ancestry, a Britishness that is differentiated in terms of how we perceive it the better part of 2,000 years on.

Many of these items, small and large, particularly coins, have come down to us, often elongated, often with slightly surreal shapes. Celtic craftsmen weren’t interested in realism, and their art was essentially not abstract but mystagogic and followed from the nature of their legends and their myths.

Here we move forward to the influence of the Roman civilization on the British Isles. This is a particularly British interpretation of a Classical legend. It’s the head of a medusa,[2] [7] the snakes as hair swirling around the actual physiognomy of the piece. Yet this piece is not really Italianate. It’s not that Classical in feel. It’s very British and even English. It was found in Bath in the West Country, and it comes to look, to my mind, as a sort of heavy piece: solemn, fiercely etched, non-Classical in its lineaments, a sort of transliteration of Romanesque art into British terms. We’ve taken their material and interpreted it in accordance with our craftsmen, and you can leap forward almost to the images on the outside of steeples in the Middle Ages from this type of art. Fierce, slightly primitive: You can almost sense an Italian of the era would wince. But we’ve taken it into ourselves and made something different out of it.

Here we have something in the same era, a British variation on a Roman theme. Two images for the price of one, one of them extraordinarily modernist looking. The one on the left, as you look at it, could almost be a piece by Elizabeth Frink, say, from the middle of the twentieth century. But again, these are British takes on Roman ideas about their gods, one from Gloucester and the other from Northumberland.[3] [9] One thing you will notice about them is their heaviness, their three-dimensionality, their earthy solidity. There’s a certain absence of Classical lightness, but there’s an ur-primeval and deeper consciousness, a more Northwestern European consciousness, not a Southern European one. Again, we’ve taken Roman cultural archetypes, motifs, and forms into ourselves, and our craftsmen have obeyed their Roman masters, but in a sense they have produced something which is irredeemably British.

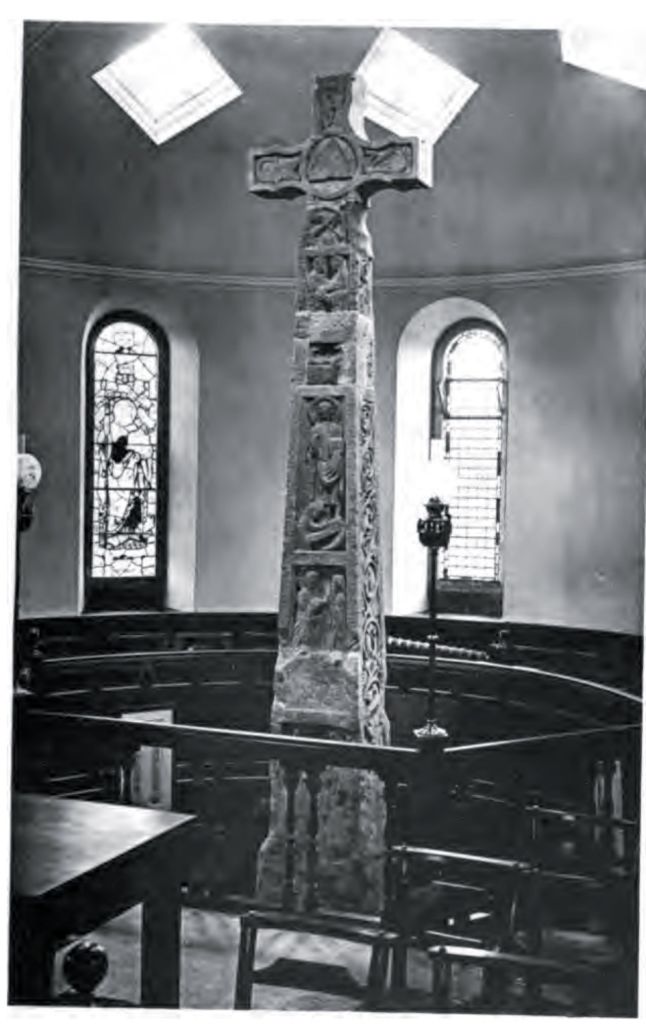

Here we have a Northumbrian Christian cross,[4] [11] leaping nine centuries forward from the last exhibit. Very Christian, slightly Romanesque, smallish figures outlined in semi-relief against the texture of the cross as it goes up. To my mind, there still seems to be certain pre-Christian iconographic elements to the piece. The thing that strikes me, though, is that differentiated from the Celtic art that we looked at before, but very much in spirit with the more Roman art that we evaluated a moment previous to this, there’s a solidity to the piece — a strength, an insularity, and a grandeur which goes through all British three-dimensional art whether Celtic, Romanesque, Christian, explicitly pagan, Restorationist, modernistic. This sense not of heaviness, but of the gentility of strength and of a sort of residential power to three-dimensional space.

Here, moving on in time, we sense a Saxon and an explicitly Germanic influence in Christian English art, as we can now call it. The sculpture is still embedded on a wall, on a plane.[5] [13] It’s partly relief, but as you can see from its three-dimensionality, the figure of the crucified Christ wants to come out of the wall and is almost, one could say 50%, three-dimensional. It’s not going to take too much for it to burst out of the wall, off the cross, and be a configured figure in its own right. Again, we see not just a Christian influence ideologically and theologically, but that element of profundity and heaviness and truth to materials and prior solidity which I believe is a quintessential part of English and British three-dimensional form. It’s interesting that these things remain extant no matter the change in historical period or the overlying culture. We pass from a primeval paganism to a Celtic influence to an influence of imperial Rome to an influence of early Middle Ages Christianity, and yet some of the abiding ethnic themes that lie behind the delineation of three-dimensional art remain the same.

Here we move slightly forward in time to an extraordinary image which could be said to be the beginning of the high-art sculptural tradition in England as it has come down to us, as it will be interpreted by critics like Orpen[6] [15] in the early part of the twentieth century just gone. This dates from 1290 and is an effigy[7] [16] made by William Torell. One of his first ones, a life-size bronze — it’s an extraordinary piece. Imagine that it’s incredibly heavy, highly wrought, the full length of a man’s course, metallic, powerful. But again, you have amidst the finery and appurtenances of the form a strength, a physical power, a solidity even in repose. Ideologically, it’s supposed to show the redemption of a Christian and knightly grace in death. But I think it very much relates, too, in its three-dimensionality many of the images that we’ve seen before. So powerful even in its metallic form that it survived the better part of a thousand years and will probably be extant a thousand years from now. This is the bringing together of stoicism in form, grace, solidity as to material, truth to materials (to use a modern slogan), and the quiet power of the English three-dimensional tradition.

Tomb effigy of Richard II [17]

Here we have an image in bronze again, highly weathered, of Richard II,[8] [18] the subject of a Shakespeare play. Again, very much seen in a Christian vogue, a Christian knightly monarch looking slightly meek and humble, how you were supposed to look in the era. Very strongly three-dimensional; good line; powerful, squat nature of the features and upper shoulders. He’s depicted slightly as an apostle. But again, these are part of the conventions of the period. But again we return to this theme of compactness, stoicism, truth to material, and solidity. In all of English and, to a slightly lesser extent, British sculpture there is this deep, quiet, and reverberating sense of power in the depiction of the face, the upper body, or the entire frame.

Christ’s resurrection, fourteenth century Nottingham Alabaster [19]

Here we have an image from the fourteenth century from Cambridgeshire[9] [20] from a provincial church. It strikes me as a very Germanic image, this one. Almost completely three-dimensional, but with a certain element of relief. But the relief becomes ever more studied, ever more withdrawn. The figures are bursting through into three-dimensionality. This is a scene of the ascent of the Christ after death, after the resurrection. He appears both as a victim and as a monarch, or celestial king. The Roman soldiers — who actually look like Medieval warriors of the time because those are the forms or archetypes upon which the anonymous sculptor is drawing — fall back in amazement and consternation before this risen being, who’s almost sort of walking out of the relief to what is perceived to be a semblance of glory.

Julius Caesar, sixteenth-century terracotta roundel [21]

Here we have a terracotta from the 1540s. It doesn’t really relate to pure English art that much, but what we see here is an opening out in the Tudor period to continental influence. So, we’re dealing with a sort of re-Europeanization, or a return of the sculpture of the ancient world in the form of a bust relating to Julius Caesar.[10] [22] But it’s the opening to intellectual ideas on the continent. And although you could say that in the Middle Ages we internalized lots of continental ideas, here are Italian sculptors coming over at the behest of the court structures of the day to bring High Renaissance material within the purview of the English tradition. And from now on we see a mixing of what existed before and the high art of the Renaissance coming over to Britain and England in order to curry its trade. We see a sort of fusion of various European styles as the whole of the European civilization is beginning to wean itself away from the Middle Ages, and it’s beginning to look towards the creation of Early Modern Europe. You have this sensibility which grows up during this century and the one to come after it which involves a gradual de-Christianization, a return of the Classical in various dimensions — this is the classicism of the ancient world — and a slight mobility and a loosening of the rigid forms of Medieval and post-Medieval art.

Here we have another example of the High Renaissance.[11] [24] It’s the lightish spirit of Michelangelo come over to England, hopped over, and in wood. It’s from King’s College Chapel in Cambridge, forcing house and academic stamping ground of the upper-class elite of the time, of course. Again, it’s the belief in all things Italian and Renaissance in spirit and style in stone, in bronze, in wood, in jewelry, in literature, and elsewhere. So, we’re taking during this period whole handfuls of Renaissance sensibility from the southern part of Europe and bringing it across and internalizing it as part of the national tradition. Now, what’s really happening here is two things: We’re opening up to a humanism which is European, we’re opening up to certain post-Christian sensibilities, and yet at the same time we’re going back to certain of the conceits and styles of the ancient world. But we don’t know entirely what they were, so we are stylizing what we imagine the ancient craftsmen did in bas relief, in two dimensions, in three dimensions, and we’re bringing it forward several thousand years as Christianity begins to loosen its hold on the European imagination and we connect via Southern Europe and its cultural influences with the Classical world.

The Wriothesly Family Monument [25]

[26]

[26]You can buy Jonathan Bowden’s Extremists: Studies in Metapolitics here [27].

Here we see a major sculpture from 1592 by Gerard Johnson the Elder. The tradition is well advanced now. This sculpture deals with death, of course, and an enormous amount of monumental masonry and three-dimensional sculpture deals with the relief of death both inside and outside Christianity. The power and solemnity of the tomb or mausoleum, the desire to incarnate oneself as a living corpse after death, the power of a provincial noble family to be seen for the entire community possibly for hundreds of years. This is the Southampton tomb at Titchfield.[12] [28] And yet it’s also of a very important patron in the history of English art. This is the Third Earl of Southampton, who was Shakespeare’s patron.[13] [29] The arts in all eras have to obtain money because they can’t finance themselves in a completely freestanding way. In this era, aristocrats and very rich individuals from the upper class would give money and be seen to give money to the arts as part of an organic tradition. But they always had a certain element of self-interest and they always wanted their family, such as through the vehicle of a tomb like this, to be the recipients of their largesse. So, the money is given. An enormous tomb of massive monumentality is built to a local dignitary. And you can sense the power in this church. Not only is it very big, very tall, very solid. There are these spear-like menhirs on the four corners of the tomb that make these stone corpses in state look like images from ancient Egypt, almost. It’s a sort of grandiloquence and power of an aristocracy that had life-and-death powers over the rest of society, brooked no word against them, and were totally in charge. It’s also the sign of a ruling group that is completely self-confident in this world and what they presume will be the next.

The West Face of the Great Fire of London Monument [30]

This is another piece, a relief but yearning and striving in its stone-like quality for three-dimensionality. This is by a grave sculptor, Caius Gabriel Cibber, a Dane, who did an enormous amount of work during this Baroque, Augustine, and allegorical period. This is a truly sort of eighteenth-century version of a Classical conceit as they attempt to realize it. Charles II pleads on behalf of art and science and the muses to restore a damaged London which has been ravaged by fire and destruction.[14] [31] It’s a sort of heroic, post-Renaissance painting in stone. Everyone’s highly idealized, everyone’s outward-looking, everyone’s made to look as noble as possible. Cibber, in turn, was an extraordinary sculptor, who’s quite famous now for influencing some modernist sculptors, because two of his most famous pieces are the grotesque and gibbering figures outside of what used to be Bedlam Hospital in South London. One’s called Melancholy and the other is called Raving Madness. They’re interesting grotesques that partly relate to Medieval art and now are still there outside the entrance to the Imperial War Museum[15] [32].

The West Pediment of St. Paul’s Cathedral [33]

Here we have a relief, again very solid in its two-to-three-dimensionality, from St. Paul’s Cathedral. It shows a Biblical scene, the conversion of St. Paul or Saul, who sees the divine light. On the road to Damascus he’s thrown from his horse, and the persecutor of the Christians becomes the founder of Christ’s Church. And yet in a strange way, to my mind, the Baroque or post-Baroque and highly individualized sensibility of the piece doesn’t have that much to do with Christianity. It’s a typically post-Renaissance work whereby Christian discourse and narrative and heritage is used as the model on which you do a modern version of a Classical sculpture. So, we’ve got the horsemen rearing up [and] being thrown from their mounts, the divine Sun coming down from the clouds, and all of these Israelites, as it were, are depicted like warriors from the ancient world who are mysteriously wearing armor and carrying weapons that are from the beginning of the eighteenth century. This dates from 1706, and it’s by Francis Bird, who’s a very famous sculptor of the period, [and] who did an enormous amount of work in and around St. Paul’s. Probably the modern sensibility would find his version of the Duke of Newcastle in that cathedral to be the most interesting of his works. This is a savage and rather grotesque piece in the form of a large sculptural tomb in which two skeletons tear apart the bottom end of an oak tree.

Here we move forward a little bit in time, but the vogue in the sensibility is still very much the same. This, believe it or not, is a bust of the then Princess, and later Queen Victoria. It’s from the collection at Windsor Castle and dates from 1829, by William Behnes.[16] [35] You notice the young Victoria is depicted much like the present Queen’s [Elizabeth II] painting by [Pietro] Annigoni as a sort of exultant and superbly modeled being, and she looks like the young daughter of a Roman Senator. But this is very much the way in which the English and British nobility wished to be perceived at that time: a certain sort of yearning and sort of expectant and transcendent quality. These busts were done for almost anyone of renown at the time, and they would have been done in her case by Royal commission and for such patronage.

Although we’ve leapt from the beginning of the 1700s to the early section of the century that follows, you notice that this type of work is all of a piece and there is a contiguous nature to English and British sculpture between the Restoration in 1660 and, say, the Great Reform Bill in 1867. You can virtually say the sensibility that masters the sculpture of this period straddling over a century and a half is the same sensibility. It’s pre-Romantic, it’s Augustin, it’s highly classical, and it’s a light, stylized early Michelangelo-driven interpretation of what the sculpture of the ancient world would have been like. There are many, of course, falsities and discontinuities because ancient sculpture was highly decorative and painted. We see it without paint, because all the paint has rotted off. We see it as white stone or, on occasion, marble, but in actual fact when these images are recreated, as they have been in the twentieth century by imagization techniques, particularly pioneered by the Victoria and Albert Museum, we get a totally different idea of what ancient sculpture was. So, this is our idea of unpainted ancient sculpture thousands of years on in order to celebrate the then imperial British aristocracy.

Lady Rachel Fane (1613-1680) [36]

And here we have another piece of stylized and slightly Baroque classicism, although more stereotypically Classical in its way. It’s of an aristocrat, the Countess of Bath,[17] [37] and it’s by Balthasar Burman. Again, it’s this attempt to heroicize, through the revisualization of the ancient world, the aristocracy from the seventeenth, the eighteenth, and eventually the first half of the nineteenth century. So, you have this sensibility which you will see in churchyards and vicarages and churches in particular up and down the country whereby the nobility identifies themselves with the Christian tradition, with the Classical tradition, the Greco-Roman and Hellenistic tradition, and wants to celebrate through patronage their power and solidity in stone.

Sir John Thornycroft (1613-1680) 1725 [38]

Here is another piece[18] [39] that relates to the style that I’ve just described. It, again, is of a provincial aristocrat or, at the very least, an august figure: Sir John Thornycroft. Whether he relates to Tory politicians with that name in the twentieth century, I’ve got no idea. This is by Andreas Carpentier. If you notice, the way in which this individual wants to be depicted, he looks as though he’s a drunk associate of a poet like Catullus in ancient Rome where he’s lying on a bed or on the floor of a party, making an allegedly witty remark, wearing a toga and an eighteenth-century wig! So, you see that people in vogue in their century wanted to be depicted as the heroes of the ancient world, particularly in literature and in the arts. So, it’s partly a fantasy that these people had about themselves, but it’s also part of the power of the West.

In the middle of the twentieth century, a rather dissident American figure called Lawrence R. Brown, who was an engineer, wrote a book called The Might of the West, and these people believed totally in the Western civilization and they believed in its domination and they believed in its civilizing mission. They believed it extended through from various incarnations in the ancient world. These were people who had no doubts about themselves, about their society, its extension imperially across the Earth, and the power of their own nationalities. They also saw themselves, Christian or otherwise, as the inheritors of the Classical tradition. Full stop.

Lady Frederica Stanhope (1800-1823) 1825 [40]

. . . in Augustin vogue. It’s Lady Frederica Stanhope from Chevening in Kent, 1825.[19] [41] Slightly daring here, because she’s actually feeding her young child, lying on her side in repose, although of course the sculpture is a tomb and is meant to imply death. But maternal expressions of any sentiments involving female sexuality would be permitted in this period. Don’t forget we are slightly before what will become the High Victorian period. We have unnecessarily restrictive views about this time. We think this period was incredibly prudish and so on, when if you looked at its three-dimensional art, you wouldn’t actually draw that conclusion. The reason for this is the classicizing and Hellenistic tendencies which are so pronounced, so naked — almost literally so in this case. This sculpture is by Sir Francis Chantrey, and it, again, is part of this idealizing tendency in the aristocracy of the day to see themselves as the British equivalents of the leaders of the Roman Empire.

Bust of George III [42]

Here we have a bust, a sculpture from the same era.[20] [43] It’s in Burlington House, which is in Piccadilly, right in the center of London, and which today is the center of the Royal Academy. Although technically private, you could regard the Academy as the leading state art institution, the National Gallery excepted, in Britain. The piece is of George III, dates from the 1770s, and is by an Italian artist and sculptor, Agostino Carlini. In the sort of somber magnificence of this truculent German who wants to be seen as a sort of Augustus, really, a sort of modern Roman Emperor. Wearing a toga, of course, which people in his era didn’t really wear. Looking solemn, looking fierce, looking statesmanlike, if rather sober-minded and sort of lugubrious. No signs of the putative insanity which would have him leaving the coach in Windsor Great Park and engaging in excited conversation with the oak trees.

William Wilberforce by Samuel Joseph, 1840 [44]

[45]

[45]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here [46].

Yes, here we have a major monumental piece of sculpture: life-size, very biographical, very characterful. The classicizing and heroicizing elements are downplayed, and we have a certain representational portraiture in stone and, of course, in three dimensions. This is in Westminster Abbey, and it’s of the reformer and anti-slave trader William Wilberforce. Now, this piece, which is very characterful — and you can sense the liberal-minded Whiggish sentiments and sensibility of this very upper-class gentleman of his era, influenced by humanism, Enlightenment, and post-Renaissance ideas as well as the dawning of the high liberalism of the middle Victorian period, as well as extremely Christian sensibilities. Nevertheless, there are different ways of looking at Wilberforce, because many slave-owners of the time wanted to introduce a mass class of black slaves beneath the white proletariat in Britain. So, paradoxically, and in a rather revisionist vogue, it is possible to see Wilberforce as a man who may not have wanted this, but he did preempt the creation of explicit multiracialism in Britain by maybe 120 odd years before it actually began to get underway in the middle of the twentieth century.

Venus Reclining on a Sea Monster with Cupid and a Putto, 1790 [47]

Here we have very much a Classical image from the same period, the late 1700s: Venus Reclining on a Sea Monster with Cupid and a Putto by John Deare.[21] [48] An aristocrat[22] [49] would have commissioned this. We see her stroking the head of a horse, a rather serpentine-looking horse. Again, quite an erotic piece, a nude. You’re a philistine if you’re against it. A very important point here: In nearly all Indo-European or Aryan art, there’s a strong concentration on the body and on the physicality of the body and the sexual delineation of the body, it has to be said, particularly in three dimensions. This is very much the pre-Christian tradition of the Hellenes and of the ancient world. This corporeal element, this purely bodily and physical element, is at the core of Western art and Western sensibility in complete contravention to the Islamic civilization, for instance, which completely disprivileges the depiction of the face, the hands, the body, and believes that all corporeal images, whether the three- or two-dimensional, are non-transcendental and erotic and therefore are forbidden. Extreme forms of Orthodox Judaism, which disprivilege art, are the same. You see in this tradition a very strong element of core Western art — strong enough even to resist some of the critical and censorious blandishments of Protestant Christianity.

Yes, this is a slightly sentimental piece in mock Classical vogue. It’s by a female sculptress, Anne Seymour Damer. It’s of the dogs. It’s very Victorian in sentiment, if you like. It’s a sentimental piece about two dogs. There’s nothing really much more to say about it than that. It does relate to the sort of art that Landseer produced in the middle of the Victorian period, and in sculptural terms Sir Edwin Landseer did the lions in Trafalgar Square that face away from the column with Bailey’s form of Nelson triumphant and heroic at the top of the column, the whole thing originally conceived by the architect/sculptural designer William Railton.

Yes, here we have a monumental piece in St. Paul’s Cathedral by the famous sculptor, John Flaxman, best remembered now in art history as a close friend to William Blake, who was then very obscure. It’s a heroic image of a British marshal and naval hero,[23] [52] but again, you notice the overwhelming desire to classicize. Britannia is behind him with the trident. Various heroic maidens and sort of nymphs reach out to him in stone. It’s an absolutely enormous piece. Imperial lions exist to one side, looking slightly sleepy. This is the Earl Howe. You notice in its solidity and in its power and its monumentalism and its neo-classicism extreme imperial strength and total certainty. This is increasingly the sculpture of the nation-state that believes it’s born to dominate the planet.

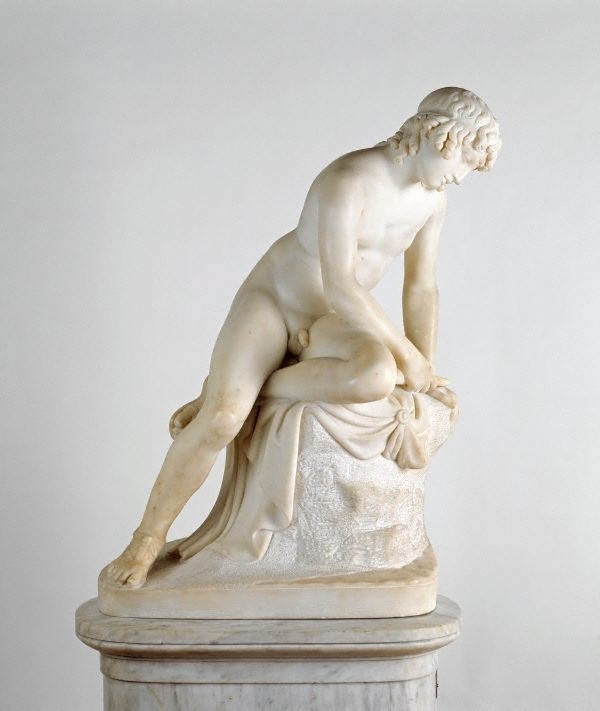

Here we have a piece of high Classicism, or neo-Classicism. It’s in Flaxman’s spirit. It’s just on the cusp of the Victorian era in the 1830s. It’s Narcissus[24] [54] as he stares down at a mirror or water, of course, in love with himself. A naked male. Highly Hellenistic and late Roman imperial. It’s part of what will become the quintessential sculpture of the Victorian period as chronicled by a historian called William Gaunt, in his two-volume history called Victorian Olympus.[25] [55] This was very much the tendency that the middle to high Victorian period wanted to exemplify, particularly in what might be called establishment or top-down art. It was the belief that we are the inheritors of the Roman imperial tradition, that we were the new and the greatest empire since Rome, that we were increasingly coming during this period to dominate at best a quarter of the planet. This was the art reaching back 2,000, 2,500 years to the Classical dawn of our civilization.

It’s also interesting to raise two cultural points here. The first is that this tradition sees Britain as the inheritor of the Classical world without any equivocation. The imperial or neo-imperial role of the United States in the twentieth century and official American art, particularly from the early part of the nineteenth century, is very much still in this vogue. The art of Washington, DC today is this type of art. It’s effortlessly imperial, not particularly Christian, and it’s essentially neo-Classical in an extreme manner. The other interesting thing to point out is that in the twentieth century, from a liberal perspective, this is the sort of art, certainly after the era of the Great War between 1914–1918, that will become associated with what will be regarded as totalitarian regimes of Left and Right.

Here is the extension of this type of Classicism to the New World, but it could be anywhere in England, Scotland, or Wales. This is from 1775. It’s a colonial piece[26] [57] from the southern United States, from the state of Virginia. This would obviously be of the master and slave-owner of the period. It would be emblematic of the Southern ruling aristocracy that would only go down in the 1860s, that part of the century later in the Civil War. So, we’ve got a sculptor here called Richard Haywood and you can see the monumentalism of the piece. It’s at least life-size, as you can see from the people who are transfigured in the background of the photograph.[27] [58] It’s raised — almost like a Donatello Renaissance sculpture from the middle of the second Christian millennium — on high. This was the Hellenistic pose of white rule in the 1700s on both sides of the Atlantic.

Here we have a mausoleum. It’s from the Victorian period by Peter Hollins.[28] [60] It’s of Mrs. Thompson, who’s probably an upper bourgeois as much as an aristocratic figure, maybe died slightly early in life and therefore the family paid for this enormous tomb in the local priory underneath some stained glass. The sculpture would be at least life-sized, and she’s depicted in a neo-Classical vogue lying on a bed which is actually her tomb where her corpse is. So, you see in this art the desire for resurrection of the body in accordance with high Anglican and post-Catholic sensibility. You also see the power of local powerful families. We’re seeing a situation where it’s not just the monarchy, it’s not just the aristocracy, it’s not just imperial rulers who think of themselves in this way, but it’s major provincial families within England in their own areas and localities, squires and so on, who want to see their corpses and their memories of themselves and their wives done up as if they were the consorts of Roman Emperors.

It’s again from the middle of the 1700s. It celebrates provincial strength and aristocratic license. It’s of Sir Jacob Gerard.[29] [62] It’s from Norfolk, in the east of England. Here we’ve got a sculptor who gives a rather solid Classical and three-dimensional representation to a provincial aristocratic family. One is reclining and lying, presumably in death. Others adopt a Roman imperial pose around the near corpse. It’s again part of this transfiguring desire to see people in a Romanesque and imperial manner completely out of keeping with the society in which they’re living, but it’s this desire to see themselves as the repository of the Roman imperial and Hellenistic culture of well over 2,000 years before.

Here we have another life-sized piece,[30] [64] Very much in a Classical vogue, but more after the realistic delineation of an eighteenth-century gentleman. This is actually of the Gothic writer William Beckford, who wrote Vathek, which is an extreme horror story in sort of high-art terms of its period. Quite militant, atheistic, sort of amoral, and he was a bit of a so-and-so. He’s captured here as he would have liked to have been seen by both himself and doubtless his favorable contemporaries. This is from Ironmongers’ Hall, and it’s by Moore. Again, the importance of these pieces is their monumentality. This is life-size in stone.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [65]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[66]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[66]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] [67] Bowden is referring to the Torrs Pony-cap [68], found between 1820 and 1829 in the county of Kirkcudbrightshire, Scotland. The original image Bowden presents is missing the horns found with it, but it is accepted that the pony-cap had the horns attached, and together they are known as the “Torrs Chamfrein.”

[2] [69] Bowden is referring to the Gorgon centrepiece on the pediment of the temple of the Sulis Minerva [70], Bath, Somerset, England.

[3] [71] Bowden is referring to the head of Antenociticus [72], pictured, found at the outpost at Benwell, at Hadrian’s wall in Northumberland in 1862. It can be found at the Great North Museum, Hancock, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

[4] [73] Bowden is referring to the Ruthwell Cross [74], probably dating from the seventh century, in the village of Ruthwell, Scotland. The carvings depict various Biblical scenes.

[5] [75] Bowden is referring to an eleventh-century carving at Romsey Abbey [76]. Despite being an “abbey,” Romsey abbey is a very large and ornate church dating back to 907 AD. This life-sized carving is on an outside wall and features the hand of God descending from the clouds above Christ.

[6] [77] It is unclear who Bowden is referring to. He may mean Sir William Orpen, a First World War artist, in the sense of reinterpreting this style through painting.

[7] [78] Bowden is referring to the Tomb effigy of Queen Eleanor of Castile (d. 1290), wife of Edward I, in Westminster Abbey [79], London, England, cast in gilt bronze by William Torell. Torrell is also known for his tomb effigy of Henry III.

[8] [80] The bronze effigy of Richard II (King of England 1377-1399) on his tomb in Westminster Abbey. The effigy was made after his Queen’s death (Anne of Bohemia) in 1395 by Nicholas Broker and Godrey Prest.

[9] [81] This polychrome alabaster panel is currently held by the British Museum, asset number 1101924001. It depicts Christ with a crown of thorns stepping on a Roman soldier (in thirteenth-century English armor) as he exits the tomb. Interestingly, the soldiers all sport identical drooping handlebar moustaches.

[10] [82] Bowden characterizes him as “the Roman Emperor and once conqueror of Britain.” Caesar beat the Britonic army, but did not settle Britain or occupy it. The bust is part of a series of gilded and painted terracotta roundels at Hampton Court Palace [83], commissioned in the late 1510s. They were produced by Giovanni da Maiano, a contemporary of Michelangelo, out of local London clay.

[11] [84] ‘Plate 182: King’s College Chapel, Screen, W. Face’, in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge (London, 1959), p. 182. British History Online [85] [accessed 22 December 2022].

[12] [86] The Wriothesley Monument in St. Peter’s Church, Titchfield. This is the tomb effigy of Henry Wriothesley, Second Earl of Southampton, with that of his mother Jane Cheney above. On the far side, unseen, is a third effigy of Thomas Wriothesley, his father, the First Earl of Southampton.

[13] [87] Henry Wriothesley, the Third Earl of Southampton, does indeed have his remains interred within this tomb, though there is no effigy of him. He appears as the kneeling figure on the right panel beneath his father.

[14] [88] Bowden is referring to the sculpture “. . . on the west panel of the pedestal of the Great Fire of London Monument facing Fish Street Hill. It is a basso-relievo which represents the King affording protection to the desolate City and, freedom to its rebuilders and inhabitants.” The monument itself [89] is 202 feet tall (the tallest isolated stone column in the world) and can be ascended by an internal staircase to a public balcony, affording a view over London.

[15] [90] They are now on permanent display at Bethlem Museum of the Mind, Bethlem Royal Hospital, Beckenham, Kent.

[16] [91] “Queen Victoria, when Princess Victoria of Kent (1819-1901), 1829 [92].” Part of the Royal Collection Trust. Image from Sixty Years A Queen: The Story of Her Majesty’s Reign by Sir Herbert Maxwell, 1897.

[17] [93] A life-sized marble statue in St Peter’s Church, Tawstock.

[18] [94] Tomb of Sir John Thornycroft, carved by Andrew Carpenter (Andreas Carpentier) of London, in the south chapel at St. Mary’s Church, Bloxham, Oxfordshire.

[19] [95] She is buried with her husband and child in a vault beneath the Stanhope Chantry at St. Botolph’s in Chevening, Kent, England. This pose specifically refers to her death during childbirth at age 22. The sculptor, Sir Francis Leggat Chantrey, lived 1781-1841.

[20] [96] Bust of George III, 1773, Agostino Carlini RA (1718-1790)

[21] [97] On view at Getty Center, Museum West Pavilion, Gallery W101.

[22] [98] Sir Richard Worsley, Seventh Baronet [99]. This was commissioned during his time as a Member of Parliament for Newton on the Isle of Wight, something that probably at least partly inspired the aquatic-themed commission.

[23] [100] Admiral Howe (1726-1799) [101].

[24] [102] Narcissus, 1838, by John Gibson RA (1790 – 1866) [103]

[25] [104] Victorian Olympus is actually the last in a three-volume trilogy covering Victorian art movements.

[26] [105] Statue of Lord Botetourt [106] in front of the Sir Christopher Wren Building at the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia. The original (pictured) has since been moved and replaced with a bronze replica.

[27] [107] Bowden is referring to a much lower quality photograph not used here.

[28] [108] The recumbent effigy of Sophia Thompson (d. 1838) on her monument by Peter Hollins in the north transept of Great Malvern Priory Church [109]. She is depicted turning in joy at the moment of her death to see the risen Christ.

[29] [110] Sir Jacob Garrard of Langford, Kent, First Baronet; his son Sir Thomas Garrard; and his grandson, Sir Nicholas Garrand. The monument is located on (British) Ministry of Defense property, in Langford Church, Norfolk, and is inaccessible to the public without special permission. All three figures wear Roman armor.

[30] [111] Alderman William Beckford by John Francis Moore. The statue is of William Beckford, Senior (baptised 19 December 1709-died 1770), but Bowden mistakes him for his son, also named William Beckford, an art collector and novelist (1760-1844). The statue “shows a stately Beckford clutching Magna Carta in one hand and posed perhaps mid-debate [112].”