Twelve Months Later: Anthony Burgess’ 1985

Posted By Mark Gullick On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledNot merely the validity of experience, but the very existence of external reality was tacitly denied by their philosophy. — George Orwell, 1984

American college students have said, ‘Like 1984, man’, when asked not to smoke pot in the classroom or advised gently to do a little reading. — Anthony Burgess, 1985

I made a half-hearted New Year’s resolution not to mention Orwell’s 1984 this year, not once. Like most of these Janus-faced pledges, however, it didn’t last long. But hasn’t the book been over-visited? I have said more than once that 1984 — working title, The Last Man in Europe — has a Koranic role for dissidents everywhere, and so it should. It is now the standard reference work if you wish to understand what is happening to the West, which is why the very dangerous British “anti-radicalization” group Prevent have warned that anyone reading the book is in danger of being radicalized. I will be writing about this group in a future episode, but regardless of their sham and strategic fears, surely the book has been done to death. Everyone now stifles a yawn when someone writes that Orwell’s book — second working title, 1948 — was supposed to be a novel and not an instruction manual. How many more ways can one look at a work of art? I reviewed 1984 here [2]at Counter-Currents, if you are interested, but I reviewed is as a love story.

I thought perhaps it was time to look more closely at the other dystopian novels that accompany Orwell’s grim vision of eternal boots on human faces, if they haven’t already been eaten by rats. “Dystopian,” by the way, is one of those words mainstream media journalists have recently fallen in love with, not because they understand its Ancient Greek roots (because they won’t and can’t), but because they think it makes them look clever, like English people who say Paree instead of Paris even though they speak no French.

Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We (which Orwell had read) also have much to say about our present predicament, but so too does Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. The book is almost as iconic as 1984, although this did not please Burgess at the time of the controversy about Stanley Kubrick’s film of it. Some of Burgess’ fan-club — one he richly deserves — pretend that John Burgess Wilson (Burgess’ real name) was upset at the violence associated with Alex DeLarge and his bunch of droogs. Not at all. Burgess was irritated that A Clockwork Orange came to overshadow his other work because of the controversy. Also, he felt that he had ended up taking the heat for a fire someone else started.

A clubbable, very English man, Burgess was a regular on talk shows, during one of which he informed the audience, in a bored tone, that every time a couple of nuns got raped somewhere in England after the film came out that it was he who got the call from the press, while Kubrick was notoriously reclusive. It was Kubrick, incidentally, and not Burgess or the Lord Chancellor who pulled the movie from distribution.

Burgess was a polymath, a Mancunian Renaissance Man. Born a First World War baby in 1917, and dying in 1993 at the age of 76, his early career was patchwork. For the first 38 years of his life, Burgess published no books. During the second 38 years, he wrote over 50 novels, histories, and books of criticism. But he was only a late starter in literature, having been a journalist and critic, as well as a very talented musician. His mother was a music-hall singer and his father a cinema pianist, and so music was in his blood. He composed a lot of performed music, and I find his piano concertos strange but intriguing.

He was also a very funny man, with that peculiarly dry, English sense of humor. As noted, he was popular on British chat shows and was good value for money. In what was quite a ribald joke for the time, the 1970s, but with a delivery worthy of Rodney Dangerfield, Burgess informed his host that his doctor had told him sexual exercise was a good idea for men of his age, but that it shouldn’t be too exciting. Burgess’ doctor therefore suggested that the writer only have sex with his wife.

Burgess’s first wife, Lynne, became a chronic alcoholic and died of the disease most associated with that lifestyle, cirrhosis of the liver. His second wife, whose name Liana curiously echoed that of his first, was Italian. Among the rag-shop of memory, I recall reading an interview with Burgess conducted not long before his death in which at one point, with Burgess and the interviewer seated pleasantly in his Italian courtyard, the writer’s wife came out and asked Burgess a question: “Anthony, what is the name of the deep-Grammar man?”

“Chomsky.”

[3]

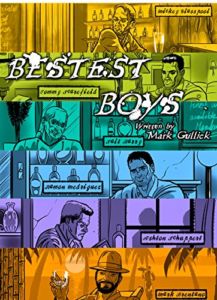

[3]You can buy Mark Gullick’s Bestest Boys here [4].

I thought then, as I do now, what a pleasant life that must be to lead in one’s old age: an intelligent Italian wife, one’s typewriter, and the agreeably temperate Italian weather. The lasting impression of Burgess is that he was a troubled man — which of us isn’t? — but ultimately a fulfilled one. Liana adored the fact that Burgess bought a self-contained camper van — a very English version of the Winnebago — in which they toured Europe as cultured Bohemians.

Burgess’ prodigious oeuvre showed a trace-work of obsessions, namely language, music, good and evil (territory familiar to any lapsed Catholic, which he was), and James Joyce. The Irishman wrote just four books in his lifetime, but Burgess published five about Joyce. Burgess also wrote another book which is an excuse to break my New Year’s resolution: 1985.

Written in Monaco in 1978, 1985 is intended as a sequel to Orwell’s book. Burgess insisted that it be published with an accompanying selection of essays on 1984, as well as mocked-up interviews with an interlocutor about Orwell’s themes. We look to books from the past which predict the future with a forensic eye, and just as Orwell foresaw much of the repressive machination of the modern state, so too was Burgess culturally clairvoyant, as the extraordinary opening line of 1985 (a clear pastiche of the opening line of 1984) establishes: “It was the week before Christmas, Monday midday, mild and muggy, and the muezzins of West London were yodelling about there being no God but Allah: ‘La ilaha illa’lah. La ilaha illa’lah.’”

We can hardly expect Orwell to have predicted the rise of Islam in the 1940s, but 30 years later, Burgess’ opening — and a major thread throughout 1985 — develops into near-perfect futurology. It is not Big Brother who is the threat in Burgess’ book, it is Big Muhammad.

In 1985, the Muslims are in charge:

The Arabs were in Britain to stay. They owned Al-Dorchester, Al-Klaridges, Al-Browns, various Al-Hiltons and Al-Idayyins, with soft drinks in the bars and no bacon for breakfast.

Burgess also uncannily predicts the change in the British economy Islam was to bring with it, rolled up in the same magic carpet as their ignorance and hatred of women — and gays, something the Leftist British homosexual community is discovering to its horror – as well as their boring and retarded book, the Koran. Here is current immigration foreshadowed in Burgess’ crystal ball: “To remind Britain that Islam was just not just a faith for the rich, plenty of hard-working Pakistanis and East African Muslims flowed in without hindrance.”

Get rid of “hard-working” and you have the beaches of Kent at the time of writing. I make an exception for Albanian Muslims, who are hard-working in the twin trades of drugs and violence. And one character makes a telling observation about the effects of Islam building a financial infrastructure in the heart of the dar al harb:

“You seem to regard London as part of Islam.”

“It is the commercial capital of Islam, Mr. Jones.”

Sharia law makes precisely the same creeping progress it is currently seeing in London, with “two men and a dog rolling a barrel of rum round the roads, in danger from the Muslim police, trying to keep the memory of liquor alive.”

There are already Muslim-controlled areas of England’s capital city — and my home town — where posters on lamp-posts instruct visitors that alcohol, immodest dress, homosexuals, and dogs are not permitted. Welcome to London, inshallah.

But Burgess’ predictions concerning the caliphization (it horrifies me that spellcheck recognizes that word) of Britain is not his only correct reading of the runes. Televisions — or “telescreens” in Orwell — are intrusive and punitive data-gatherers, whereas in Burgess’ book they are exactly what they remain: a succubus of whatever remains of a young person’s intelligence. “Home was anywhere,” the main character says of his daughter’s attitude, “so long as there was a telly.” The TV, and its bastard offspring, the Internet, is a pernicious influence perhaps unappreciated until it is too late. It is also a medium complicit in another of Burgess’ correct predictions, that of the curtailing of freedom of speech we are seeing accelerate today. “We’re moving in the direction of increasing restrictions on speech as well as action,”replies Burgess in one of the appended “interviews” that bookend 1985.

The novel follows Bev, who has fallen from grace in his teaching job for the equivalent of Orwell’s Wrongthink. I had to smile a wry smile at the names of two of Bev’s adversaries, Lieutenant Derrida and Captain Chakravorty. The first name will, I’m sure, be familiar to you as an arch-enemy of the political Right, aligned as he is with postmodernism. But why Chakravorty? Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak was the translator of Derrida’s Of Grammatology, as reviewed by me at Counter-Currents here [5]. Burgess was an accomplished linguist — see the story of nadsat in A Clockwork Orange, an amalgamation of British street slang and Russian — and would probably have read Derrida’s book, however averse he was to the postmodern.

The bad guys in Burgess’ novel play classical music on their own instruments. This idea — perhaps what Jonathan Bowden hinted at in his phrase “the cultured thug” — is an echo of A Clockwork Orange, in which little Alex, a violent psychopath, is enchanted by Beethoven. Years later, Hannibal Lecter will make Bach’s Goldberg Variations famous while eating people’s tongues straight from their mouths. Good and evil, as Aristotle noted, can exist in the same person. Burgess ponders the same point in the essay “Cacotopia”:

A commandant who had supervised the killing of a thousand Jews went home to hear his daughter play a Schubert sonata and cried with holy joy. How was this possible? How could a being so dedicated to evil move without difficulty into a world so divinely good? The answer is that the good of music has nothing to do with ethics.

This is an answer so crystalline as to suggest that Burgess may have missed a calling as a moral philosopher.

There is a sense of patched-together didacticism about 1985, and it is sometimes reminiscent of Robert Tressell’s 1914 and boldly socialist novel The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists, in which political tracts are bolted on to the narrative. But Burgess is a brilliant writer, never clunky and always wry, and ultimately an English writer who is a great advertisement for that particular branch of the trade. There are flashes of insight as well which dovetail perfectly with Orwell. Both 1984 and its Burgessian sequel have a central and defining symbol. Orwell has the face and penetrating eyes of Big Brother, staring from every street corner. Burgess has a flag more allied to the technocracy we see today: “Bev looked up at the towering stained stucco to the flag flapping at the top — a silver cogwheel on a blood-red background . . .”

Socialists are obsessed with mechanical imagery, and this is never better shown than in Fritz Lang’s 1927 movie Metropolis.

Burgess’ 1985 is a perfect companion piece to Orwell’s 1984. I would love to know if Michel Houellebecq read Burgess’ novel before he wrote his own novel, Submission. These writers are also teachers, and we should heed the lesson. Burgess himself had an epiphany while teaching in Malaya. “I came here as a teacher,” he said, “but I left as a writer.”

I have read nothing like all of Burgess. As with many other writers, there is but one lifetime. Every English reader knows Burgess’ most famous work. Paul Cook, The Sex Pistols’ drummer, once said that “I’ve only ever read two books, one about the Kray twins and A Clockwork Orange.” I do know Burgess’ greatest comic character, Enderby, and the Malayan Trilogy, as well as Earthly Powers, many years ago.

But I still feel uncomfortable about signing off with a piece of personal and professional correspondence sent to Burgess by his commissioning editor. It is just too funny to omit, and I hope it is not disrespectful.

Burgess had somehow got himself a writing gig at Rolling Stone, and in 1973 was in Rome. Commissioned by the magazine to do a “thinkpiece,” he replied that he was short on ideas, but would Rolling Stone accept part of his new novel in lieu? Sadly for Burgess, his commissioning editor was Hunter S. Thompson, and I will leave you with his reply to the British novelist:

Dear Mr. Burgess,

Herr Wenner has forwarded your useless letter from Rome to the National Affairs Desk for my examination and/or reply.

Unfortunately, we have no International Gibberish Desk, or it would have ended up there.

What kind of lame, half-mad bullshit are you trying to sneak over on us? When Rolling Stone asks for a “thinkpiece,” goddamnit, we want a fucking Thinkpiece [sic] . . . and don’t try and weasel out with any of your limey bullshit about a “50,000 word novella about the condition humaine etc.”

Do you take us for a gang of brainless lizards? Rich hoodlums? Dilettante thugs?

You lazy cocksucker. I want that Thinkpiece on my desk by Labor day. And I want it ready for press. The time has come and gone when cheapjack scum like you can get away with the kind of scams you got rich from in the past.

Get your worthless ass out of the piazza and back to the typewriter. Your type is a dime a dozen around here, Burgess, and I’m fucked if I’m going to stand for it any longer.

Sincerely,

Hunter S. Thompson.

I have had some tetchy letters from editors in my time, but this puts the tin hat on everything. Anthony Burgess and Hunter S. Thompson: Two writers united by a common language. It must be the year 1985.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [6].